<MENU

<MENU

4A. LANGUAGES ACROSS OCEANS

LANGUAGES OF THE EXPANSIONS OF THE "KUNDA" CULTURE INTO THE OCEANS

Synopsis:

These UIRALA

articles/chapters are the result of a multidisciplinary process,

which is mainly based in archeological discoveries of the past century,

but includes considerations in other areas like languages. While

studying languages in isolation produces few revelations, when

languages are looked at in conjunction with all the other evidence in a

multidisciplinary project, it can provide insights. The following

reflects the investigation of the languages of suspected oceanic

expansions from Finnic northern Europe. Ideally the reader should

have already looked at the chapters that have presented the results

from the information from the other sciences, to better understand the

language investigations and interpretations. (See also the language-related article pertaining to the interior eastward expansion of boat people to the Urals and beyond.)

Introduction:

Recent Comparisons of Northern Eurasian

Languages and conclusions that the Uralic Languages did NOT

evolve in a tree diagram sequence

Linguistics has spent a century trying to determine

the history of the indigenous languages from the Baltic to the Ural

Mountains and beyond. It has decided how languages came to be, what

evolved from what. Because the linguistic interpretation was done a

century ago, before there was any information from archeology about

what really happened, the long-held interpretation is steadily being

proven wrong. In the context of the expansion of the "Kunda" culture

boat peoples west-to-east the development of languages in this region

towards the east, has been discussed in article/chapter 2A.

But linguists have never had anything to say about

the other expansion of the "Kunda" boat people culture, mainly because

this expansion is a new one, hypothesized by myself beginning around

2002 .

Even if linguistics was interested in exploring the

expansion of the "Kunda" culture around the arctic ocean and down the

Altantic and Pacific oceans to some degree, it would face a major

hurdle that it is very difficult to employ traditional historical

linguistic analysis with languages that began diverging from one

another as early as 5,000-6,000 years ago.

Traditional comparative linguistics seeks to find

common elements in the languages studied and then find systematic ways

in which they diverged from each other and from their common parent

languages.

No methodology exists that can deal with linguistic

events in the deep past, except something attempted a few years ago. In

a 2003 paper, in reponse to questions raised by a book by A.

Marcantonio about the validity of the "Uralic" lanugages theory, the

languages across northern Eurasia were compared in terms of phonetics

and grammatical features in order to determine the linguistic distances

between them. This paper was entitled Common Phonetic and Grammatical Features of the Uralic Languages and Other Languages in Northern Eurasia written

in conjunction between linguistic departments of University of Tartu

and University of California. This paper by P.Klesment, A. Künnap, S-E

Soosaar, R. Taagepera, had to find some kind of methodology that could

reach back further in time to determine closeness between the

languages.The methodology involved identifying 60 grammatical or

phonetic

features, and then finding which of the languages possessed that

feature. The more of the features were found also in Finnic languages

the greater the "Finnicity" of the language, the more of the

features

were also found in Samoyedic languages, the greater the

"Samoyedicity". Words were not dealt with since words change more

readily than the structural features of languages. And the study only

covered northern Eurasian languages, and avoided isolates like Basque

and Ainu.

Page 3 and 4 descibe the aim of the study. I reproduce some of the text below.

The

aim of our study is to present a graphic overview, in the form of maps,

of some common features among Uralic and some non-Uralic neighboring

languages in their present forms: Indo-European, Altaic and

Paleo-Siberian (see Map 1). We abstain from including some

geographically remote languages — from the point of view of Uralic —

e.g., Basque, Caucasian, Dravidian, Ainu, Korean and Japanese, among

the Indo- European languages Albanian, Greek, Armenian and

Indo-Iranian, and among the Paleo-Siberian languages Gilyak (or Nivkh)

and Ainu. A few indispensable comments and conclusions are added to the

maps. At this stage, it is not our purpose to discuss the possible

origin of the common features but only to note their present existence.

......

We

deal only with phonetic and grammatical similarities, leaving aside

vocabulary as an easily moving and changing aspect. As Uralists, we

proceed from the Uralic language group, dividing its languages into

conventional subgroups. For the sake of a more lucid overview, however,

we present the other languages in broad groups, with a single exception

— dividing the Indo-European language group into Germanic, Baltic,

Slavic and “other Indo-European languages”. Such a division into

subgroups allows us to show to what extent features common with

non-Uralic language groups/languages (and Indo-European language

subgroups) occur in various Uralic languages.

......

Our study was instigated by Angela Marcantonio’s The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics (2002),

which carries out an extensive lexical and grammatical analysis.

Overlaps of Uralic languages with neighboring languages lead her to

disagree with the traditional view that the languages grouped as

“Uralic” form a separate linguistic node (condensation, entity or

intertwinement). Marcantonio’s analysis suggests a mental picture where

the Uralists have drawn a circle on the surface of the sea and argue

that inside that circle there is peculiar Uralic water, distinct from

the surroundings and with only a little “borrowed” water from what encircles it.

....

Marcantonio considers the comparative

method, used by traditional Uralists, debatable in principle (and she

has a point), but she shows that even the method itself is used in

Uralistics in a most inconsistent manner. Strict observation of the

rules of the method is replaced by some general impression or

“feeling”. When reconstructing the Proto-Uralic word stock,

irregularities are mentioned but then ignored, and the lack of evidence

in a given Uralic language is interpreted as the word being lost in

that language. Therefore, most Proto-Uralic words have not been

reconstructed in accordance with the established phonetic laws, based

on direct evidence in actual Uralic languages. Instead, they are often

grounded in reconstructions of intermediary proto-languages, such as

Proto-Finnic-Permic and Proto-Samoyedic, deliberately neglecting

incompatible Ugric data

....

It will be seen that our study

confirms the existence of a Uralic group, distinct from its neighbors,

but some issues raised by Marcantonio remain. A clear language tree

within the Uralic group does not emerge. At the very least, it would

have to be complemented by a hefty dose of “languages in contact” —

contacts both inside the Uralic group and outside of it.

The study was intended to determine from a general

comparison of grammatical and phonetically features whether Marcantonio

was correct in claiming the traditional "Uralic Language Family"

was an arbitary circling of an area and artificial rationalizations.

While it appears to have disproved Marcantonio's claim, it actuallly

proved that the century old concept of a "Uralic Family" has been

false. To quote the study:

...our study confirms the existence

of a Uralic group, distinct from its neighbors, but some issues raised

by Marcantonio remain. A clear language tree within the Uralic group does not emerge.

This absence of a clear language tree is obvious from the story of the

expansion of the boat peoples since the end of the Ice Age. As

you will recall from previous articles/chapters and covered in detail

in chapter 2A, the languages defined as "Finno-Ugric" arose not from a

family approach (where one language evolves out of another in a

sequence that creates a tree diagram) but from a rapid expansion

followed by in situ divergence according to geographic boundaries,

notably water system boundaries. At most one can view it as a

lingjuistic bush - lot of branches arising from the same stem rather

than a sequence of branching - and that this bush originated in the

flooded lands south of the glaciers in the south Baltic.

However the study was limited to Eurasia an omitted

Ainu and Basque, and therefore languages far from "home" have not yet

been given attention. Obviously traditional linguistic methodology does

not work there too, because it does not support the

sequence-of-branchings model either. The oceanic boat peoples simply

expanded rather rapidly and lived their lives for generations changing

in situ, to some degrees influenced by indigenous neighbouring peoples

in their far-off locations. We saw this was especially the case for

Ainu and Basque, who were located in the middle of a soup of peoples,

cultures, languages, and genetics.

The proposal we offer here, that there was an

expansion of boat peoples of "Kunda":culture origins that expanded as

far as the costs of the Pacific Ocean, is still realtively unknown,

since it originates from me, the author of the UIRLALA pages, and

linguists are not even considering it.

But from a linguistic point of view, it is necessary

to prove that the languages of the descendants of these distant

immigrants actually demonstrate origins in the "Kunda" origins. Thanks

to studies like those cited above, it is becoming acceptable to NOT

view the origins of Finnic languages in northwest Eurasia in the Urals

but within the northwest and having evolved in situ.

Proving that a distant language is related to the

descendant languages of the "Kunda" culture is a great challenge,

because the approach by ordinary people is to simply compare two

languages, such as to compare Estonian and Finnish with the

distant language. The problem lies in the fact that over time words in

a language shift in their form, and shift in their meaning. Unless the

compared words are almost identical in form and meaning, the

possibility exists that the analyst is claiming a connection where one

really does not exist.

Beginning with the

archeologically supported assumption that the modern Estonian and

FInnish languages are descended from the original "Kunda" culture from

which the oceanic boat peoples expanded, if we compare Estonian

and Finnish with the language of the Inuit peoples of the Canadian

arctic, our finding that Inuit suluk, Estonian/Finnish sulg/sulka

, all meaning 'feather', is difficult to sneer at, because both form

and meaning are so close that it is more probably the earth gets hit by

a meteor tomorrow than that this was a pure coincidence. On the other

hand if the compared words are not convincingly close, connecting the

two words can be challenged. For that reason, mere comparisons to

find closeness in form and meaning is not enough. It is necessary to

also present supportive arguments from outside linguistics. In general,

one of the arguments accepted by linguists is that words pertaining to

family have been proven to resist change, and therefore if we compare

words for family members, that chances are already high that parallels

will be found. For example, in the Inuit language I found that

word saki referred to 'father, mother, uncle or aunt-in-law'. If we compare that with Est./Finn sugu/suku 'family'. This comparison is not as close as suluk vs sulka in

form and meaning. Therefore some additional evidence and arguments are

needed. A linguist would want to remain within the realm of linguistics

and demonstrate how suku might be found closer to saki in other

dialects, or how a similar U-c-U can become A-c-I. However linguistics

arguments is complex, since the linguist must becomes deeply familiar

with both languages. It is easier to generally accept the similarity in

form as being adequate, and explain the differences in meaning.

The argument would go like this. "What does the

Finnic word suku really refer to? In modern usage, it translates as

'relative' a 'related person', 'of the same classification'. But

exactly who is our relative, and who is not. Does it include one's

father's relatives? Does it include one's uncle's relatives?

Modern usage of suku does not

care, but in ancient times, when people formed themselves into

extended family units, the people to be included was relevant. Even the

way the interior of the shared home was subdivided in terms of who

occupied what location, was relevant. Thus with this in mind the

Inuit word saki in

identifying 'father, mother, uncle, or aunt-in-law' suggests that in

prehistoric times the concept that Finnic reduced to generally mean

'relatives' originally referred to one's father and his brother, and

their wives. Inuit culture I believe places men and their brothers

close, perhaps because in the hunting activity, male assistance was

needed. It was also a guarantee of a provider for the family if

one of the male providers was incapacitated. Both saki and sugu/suki

is referred to oneself, so the word relative basically only included

'immediate patrilineal relations'. Inuit culture was so dependent on

the male hunter, that everything that could be done to support

successful hunting activity, was done. It is clear that one could

write an entire paper around why saki and suku

are related words, including making references to Inuit family

structure, and those in the Finnic past. So, it is necessary for

the reader of this article to suppress any desire to sneer at the

results, and accept that all the comparisons made here CAN be

surrounded with lengthy arguments and evidence from other information

sources. Care is taken by me to simply not offer examples that do need

lengthy arguments and additional evidence. Our purpose is not to

produce a linguistic document but simply to present enough evidence of

parallels to convincingly show that the archeological evidence is

indeed supported by linguistic evidence. Do not read this article in

isolation from the earlier evidence from archeological investigations

over the past century or so. This theory of the expansion of a

Finnic-speaking oceanic boat people is not dependent on linguistics.

The language parallels only ADD support to the basic theory.

A Review of How Languages Evolve

THE TYRANNY OF TRADITIONAL HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS METHODOLOGY

Traditional comparative linguistics needs

to find words that appear to

have arisen from the same origins, and then by assessing systematic

shifts in phonetics, etc. to theorize which languages evolved from

which. A century ago, it was fashionable to try to find a sequence of

events, in which languages became parents of further languages. In

terms of the "Uralic" languages As we quoted above from the

Klesment et al paper, the traditional historical linguistics can be

'fudged' and linguistics is generally not very scientific and should

not pretend to be. As the study said: Marcantonio

considers the comparative method, used by traditional Uralists,

debatable in principle (and she has a point), but she shows that even

the method itself is used in Uralistics in a most inconsistent manner.

Strict observation of the rules of the method is replaced by some

general impression or “feeling”. When reconstructing the Proto-Uralic

word stock, irregularities are mentioned but then ignored, and the lack

of evidence in a given Uralic language is interpreted as the word being

lost in that language. Therefore, most Proto-Uralic words have not been

reconstructed in accordance with the established phonetic laws, based

on direct evidence in actual Uralic languages. Instead, they are often

grounded in reconstructions of intermediary proto-languages, such as

Proto-Finnic-Permic and Proto-Samoyedic, deliberately neglecting

incompatible Ugric data

When reading this, the non-linguistic scientist

realizes that linguistics, in spite of its grandiose opinion of itself,

is really no more correct than what can be determined by other

methodologies. Traditional linguistic methoology is just a

scientific methodology among other scientific methodologies. All that

is necessary that the principle of SCIENCE are respected.

In order to understand what can be done in

terms of analyzing the words descended from prehistoric languages,

compared to those descended from other prehistoric languages, we need

to understand how languages evolve. What is obvious, and which is the

greatest shortcoming of traditional comparative historic linguistics,

is that languages do not develop entirely by natural drift, but that

convergence during contact with other languages is important. The

primary circumstances of language change may be based entirely on in

situ (no migrating) divergence or convergence in accordance with amount

of lack of contact or contact with neighbouring peoples.

Here are some truths regarding language and how they can be interpreted.

THE HUMAN DRIVE TO COMMUNICATE WITH OTHER HUMANS

Humans are social creatures. and if we are able

communicate with other humans, we want to do so. Our world of many

languages is the result of barriers to communication, beginning with

great distances preventing contact, and continuing to geographical

barriers, differences in way of life, the establishing of territories

that required some degree of polarization with neighbours who might

want to intrude, or those who might want to fight to take over the

territory. But humans inherently want to live in peace with

others, and maximize communication. This is obvious from the way the

internet has exploded into world-wide communication, which is making

English a worldwide language.

DIALECTIC DIVERGENCE AND "CATCH UP"

With this in mind, in prehistoric times, with the

various barriers to contact, languages did diverge into dialects, and

in the long term dialects becoming extreme and turning into related

languages. But if circumstances changed, and diverged neighbouring

peoples came into contact again, there would be a great desire to

'catch up'. If the two languages were diverged from the same parent

language, they would find that they spoke basically the same language.

It was then easy to simply eliminate the discrepancies that had

developed. For example, today Estonian and FInnish have the word talu/talo,

but in Estonian it means 'farm' while in Finnish it means 'house'. If

they meet, they could both decide to use the word to mean 'farmhouse'.

Words that have no remnants can of course be completely abandoned. The

significance of this is that if few such opportunities to "catch up"

occur, then the languages will continue to diverge into increasingly

extreme dialects. For example, among the boat peoples, when

people settled down and became tied to farms and settlements, the

opportunities to make contact with more distant neighbours declined,

and as a result regions like entire water systems, displaying a single

language, develop into numerous internal dialects and then eventually

into distinct related languages. For example the "Finnic" languages

include some 5 or so languages, when perhaps 1000 years ago, there may

have been a spectrum of dialects of what seems a single language. A

'dialect' signifies change that is small enough that it can still be

understood without great difficulty.

By contrast, if the means of contact returns to a

region that has diverged dialectically, that dialectic divergence can

then be reversed. In history the most responsible for such a

reconvergence of dialectic differentiation has been the creation of

large scale nations. For example the region now the nation of "Estonia"

possesses a language that, although based on the northern dialect,

embraces words and even grammatical features drawn into the new

collective national language from its 3-4 original dialects. National

languages were established from the national government policies, and

then by the use of this national language in literature and media.

Today of course, the internet plays the greatest role. If the national

governments of the world and its boundaries and policies disappeared,

our world of languages would return to dialects and languages shaped according to patterns of contact or lack of contact.

(Thus in a sense, using modern national definitions of language,

such as "Estonian" or "Finnish", are modern developments, and strictly

speaking we must not pretend that we can compare them directly with

languages that are still in their original state as dialects within a

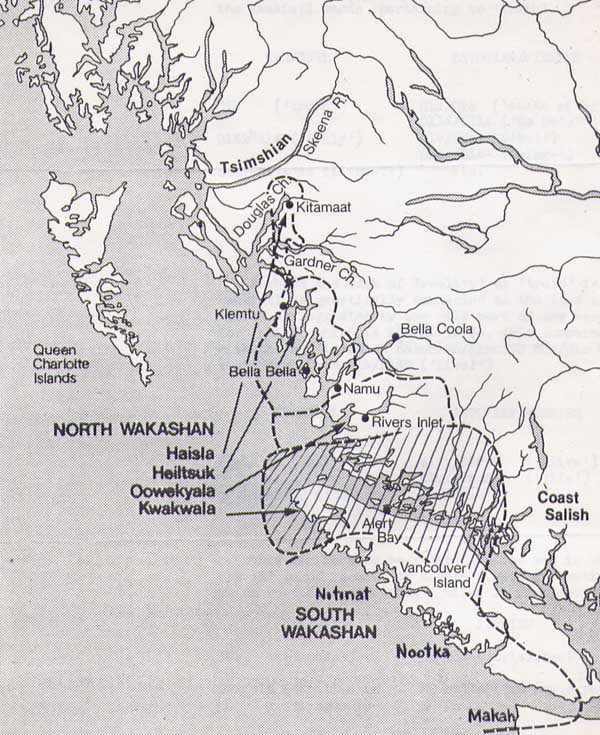

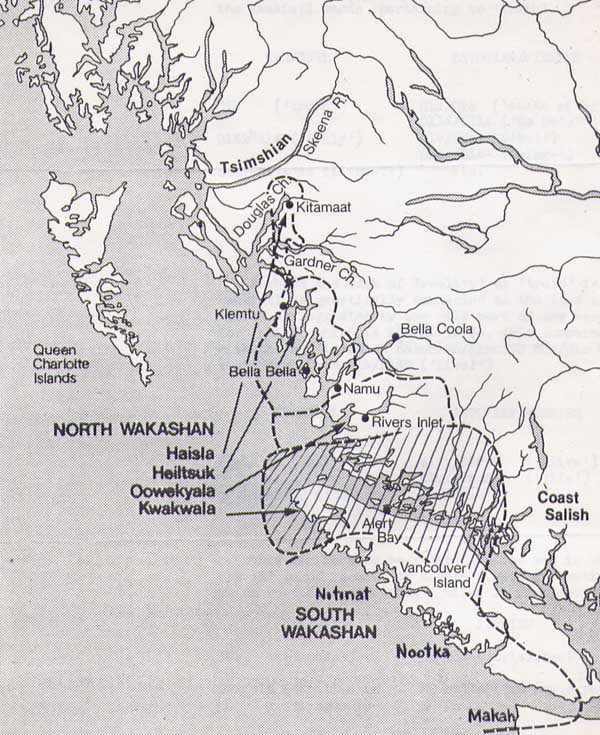

region - such as for example the Kwakiutl (Kwakwala) language within

the region of Wakashan languages.

NEED TO COMMUNICATE PRODUCING HYBRID LANGUAGES

If the two languages are no longer dialects, but are distinct

languages that neither can understand, what happens? First they

try to identify words they have

in common. If the languages are already close, the result is the new

manner of speaking throwing away the words they do not share. In this

way fragmentation into dialects is reversed, but the reversal does not

return exactly to the original common parent language. In the case of

the boat peoples lying at the roots of the Finnic languages, the reason

it remained relatively undivided over a vast region for a long time, is

because of the common practice of neighbouring peoples having regular

gatherings at locations where neighbouring waterways came close to each

other (as described in earlier articles/chapters) When those

gatherings (also found among the Algonquian boat people of the original

Canada) ended, that is when the various dialects of the water systems

broke up and eventually it all became related languages rather than

dialects.

But what if two different languages come into

contact? Initially the inability to communicate tends to be a barrier,

and if the desire to communicate was not strong, they would remain

linguistically apart. But what if in a rough northern environment the

ability, need and desire to communicate was great? What happens?

Imagine

English speakers trying to speak with French speakers for example. The

communication will reduce

to basic subject-verb-object sentences. Then each side will use the

words that are most common in their language. They will say the common

word over and over tryng to explain the meaning with gestures or

miming. In the end there is a common language consisting of the common words of both languages.

This is natural, because it is easier to remember words of the other

language that are frequently heard. Today everyone in the world

knows French "merci" 'thank you' or "bon voyage". This is because

they are used so much. It is interesting to note that the Ojibwa

(Anishnabe) Algonquian language used the word "boozhoo" for 'hello',

but it is obvious it originated from contacts with French missionaries

in the 1600's. The Natives themselves might just have said

something like 'hey!' but here were the men in black robes who always

said "bonjour" to everyone. Thus we can conclude that the language of

the prehistoric boat peoples, when meeting up with Asian reindeer

peoples in regions north of the Ural Mountains, each had commmon

expressions that were learned and remembered by the other. In the above

example, the Algonquian languages would not have had much if any impact

on French, because French was by now found widely used in two

continents, and had too much inertia to be changed. But if we

have circumstances where both languages have equal inertia, are equally

influenced by one another, then common languages will migrate equally

in both directions. This is the correct interpretation of the

langauges traditionally called the "Uralic Languages". When the

proto-Finnic boat peoples language encountered the proto-Samoyedic

Asian reindeer people language, then over the period of millenia,

commonly used words of one was adopted by the other, and vice versa.

The result would be a convergence that reduced the original difference

in the languages - more words in common, and differences weeded

out. The resulting languages then can be misinterpreted not as

the result of convergence of two different languages but divergence

from a common parent. That is essentially the primary mistake

made in Uralic linguistics.

LANGUAGE CHANGE REFLECT A HISTORY OF CONTACTS WITH UNRELATED NEIGHBOURING LANGUAGES

Is this principle applicable to the other expansion

of boat peoples via the ocean? We have to consider the

neighbouring peoples and the chances of contact that cause changes the

acquisition of commonly used words from the other language. In

the case of the Algonquian languages, we mentioned there would have

been contact with the original woodland peoples, and possibly carbou

(reindeer people). In the case of the Inuit language, there would have

been contacts too with caribou peoples. The Inuit language thus can be

expected to contain a large number of words that did not develop from

natural linguistic drift, but acquired over thousands of years from

contact with interior peoples. Note that since humans basically want to

make contact with other peoples, we cannot every assume that if other

peoples were within a reasonable travel distance that contact would be

made. They would give each other gifts and it would develop into

regular trade.

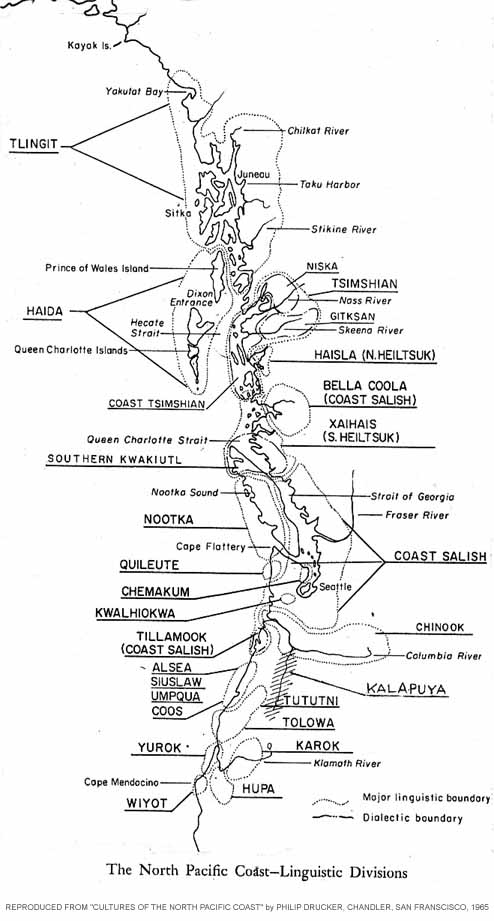

The same argument can be made regarding the Wakashan

languages and the many other Northwest Pacific coast peoples who moved

to the coast and adopted the way of life based on salmon fishing and in

some cases also whaling.

In the case of the Basque language, the great presence of

Latin-originated words from the Roman Empire, is noticable. If we

remove all words that seem to be borrowings from Spanish or directly

from Latin, the remaining words contain a considerable number of

words that resonate with Estonian. In the case of Ainu, we can

presume that most of the language borrows from other languages,

starting with japanese.

The most obvious example of the influence of other

languages can be seen in the Karok, Yurok, and Hupa languages sharing

the same river. When we look more closely at the Karok language below,

the sharing of words with Yurok and/or Hupa is obvious in the original

word list.

The reason linguistics has avoided tackling distant

languages is because no methodology exists that will address the

convergence of languages. The methodology would involve using

geographical, historical, and archeological data to ascertain what

languages were in steady contact and then becoming aware of what words

migrated over from those neighbouring languages. Merely using the lack

of development of cognates in a language as evidence of borrowing is

not enough, because it can merely reflect a lack of popularity of the

word, and also that borrowed words can be easily embraced and develop

cognates just as well as if they were inherited words. Today for

example the word "text" as used with smartphones, is developing into

many new forms in many languages even though the word "text" itself was

borrowed from English.

ON THE ENDURING OF FREQUENTLY USED WORDS

It stands to reason that

words that are used constantly, are likely to endure generation after

generation because there is no opportunity to change it. For example,

in the Venetic inscriptions, the word .e.go can be claimed to be paralleled by Estonian jäägu

because it sounds almost the same. But Estonian is 2000 years in the

future of the Venetic inscriptions, and that would mean the jäägu has

remained unchanged for about 100 generations. This is believable when

we consider Estonians may use that word 100 times a day. It means

'so be it', 'alright', 'let it be so', etc. We can therefore

conclude that if the Estonian word is actually little used, then we can

cast doubt on our hypothesis. By contrast, we found that the Venetic

word for 'duck' which was rako, has no common parallel in Estonian, but still survived as raca

within only Slovenian., located close to the region where Venetic was

found. When you think of it, in Estonian, unless you are a farmer

raising ducks, you will not use the word for 'duck' (in Estonian part)

very often. 'Duck' would be one of those words of things that we

do not use constantly, and therefore are succeptible to being replaced

by other analogous words.

This preservation of frequently used pieces of

language also applies to grammatical element and expressions. Whatever

is spoken over and over many times a day will develop an inertia,

and that it is through this realization that we can assert some

scientific integrity to comparisons.

With this knowledge, we can now understand why the

numerous words in Inuit fail to display resonances with Finnic.

We can see that they are words that are not used daily. It seems that

the words that last thousands of years are the ones that are in such

common use, that nobody dares to changed them. There can be

shifts in pronunciations, and even shifts in meaning - in both the

Inuit and Finnic - and so it is important to realize that if we begin

to look up rare Finnic words in order to find resonances, then we are

increasing the probability of arriving at false results.

In the following investigation of resonances with

Finnic in the languages of the peoples discussed in connection with the

oceanic expansion, you will note that the resonances are generally with

common words that are likely to be used constantly. In order to get an

intuitive sense of what words are common and deeply entrenched in a

language, the analyst needs to have learned the language as a child as

children are given the most common, basic language.

In

the past there have been "scholars" who have compared languages only by

thumbing through dictionaries. That approach will produce many absurd

results because in a dictionary, every word, old and new, original and

borrowed, has the same value. There is no way of determining from a

dictionary which are deeply entrenched in the language - and most

likely very old - versus those that have been recently invented or

borrowed to adapt to modern realities.

If one is not raised in the language from childhood,

there is a need to annotate a dictionary to indicate frequency of

everyday use. It would be easily achieved. Children could be recorded

speaking, and the frequency of use of the words recorded. This then

will be transfered to a dictionary. Since sooner or later a child will

say a word only spoken by his parent, so it will not exclude little

used words.

Linguists say that every millenia,

as much as 80% of a vocabulary changes. But by the same token 20% may

represent core words that are so important that there is a reluctance

to change them. After 4-6 millenia, how many of those 20% unchanging

words continue to survive? It is possible that words that resist change

after 1000 years continue to resist change. The longer one uses a word,

the longer one wants to continue to use the word. What is significant

about the interpretations below is the number of examples there

are that relate to hunting, boat-use, land, sea, water, family, and

other core concepts important to a boat-oriented people. Core words resist change.

Loanwords tend to manifest in names of new things, not core concepts.

LANGUAGES OF THE VOYAGEURS

1.

Across the North American Arctic:

Comparing Inuit with Finnic Languages

The following is a brief summary of the better

words I have found in a relatively small lexicon of Inuit words. I

avoid the grey zone of other possibilities. The grey zone is better

investigated by linguists who can add further observations to justify

their choices. Here we give only those that really jump out

strongly, and are quite obvious - needing no extensive arguing.

Full disclosure, as expected, most of the words fail

to display any obvious resonances with Finnic, and we can conclude that

these words were for little used concepts and that the words were free

to drift over the thousands of years, and/or to be influenced by

languages towards the interior such as caribou (reindeer) hunting

peoples. But even so, the rate of words that triggered apparent

resonances to my familiarity with common Estonian, was about one

word in 55, which is signficantly better than my scanning an arbitrary

North American Native language. Science is about laws of probability.

If the rate of positive hits for the target language is significantly

greater.than 'hits' by the same person with other arbitrarily chosen

languages, then by laws of probability a departure from random chance

suggests an underlyiing real reason. If we edit the word list to

remove words that would not be used constantly through hundreds of

generations, the freuencies of resonances will be even greater. (In my

investigation of a 1000 common word list of Basque, when I removed all

the Spanish or Latin words, the rate of coincidences became quite large.

The source of the Inuit words and

expressions tested in my brief study included only a few 1000

expressions. (The

Inuit Language of Igloolik, Northwest Territories,

Louis-J Dorais, University of Laval, Laval, Quebec, 1978). There is

wisdom in using common words and phrases in both languages, because it

ensures that comparison is made between the 20% or so core words that

resist change.

The following examples do not follow any

particular order. I note them in the order in which I encountered them.

Note that to make the argument strong, I have not included examples

that . Nor is the source of the Inuit words exhaustive

as only a small lexicon was consulted (A small lexicon is not

necessarily bad, as small lexicons will tend to present the most common

words, and those tend to be generally the most entrenched and oldest).

Nor are any obscure Estonian or Finnish

words used in the analysis, to ensure that we are dealing with core

vocabularies which are most likely to have endured. Note also that

anything that is grammatical in nature tends also to be old, as

grammar, representing structure, also tends to resist change. I

have selected about 54 words, which out of an original word list of

1000 words is about 1 every 20 words, which is very good.

A control experiment might only find one arguable similarity in a

couple hundred, and probably be false. Supportive evidence from outside

linguistics is very important in this kind of analysis. Exhaustive

anlysis to confirm the pairings below is beyond the scope of this

article, but anyone is welcome to investigate anything here further.

Note that we have to ignore the changings of the

endings when the forms we pair are in different grammatical forms.

THE RESULTS OF ANALYSIS OF INUIT WITH FINNIC

1. Beginning with Inuit suffixes, the one that

leaps out first is the suffix -ji as

in igaji 'one who cooks'. This

compares with the Est/Finn ending -ja

used in the same way, to indicate

agency, as in õppetaja 'teacher, one who

teaches'. Indeed Livonian

(related to Estonian) uses exactly -ji This ending would have been in common use, so there would have been an ancestral version that has survived millenia.

2. The Inuit infix -ma-

as in ikimajuq 'he is (in

the situation of being) aboard'. The Estonian/Finnish use of -ma/-maan

in a similar way describes a situation of 'being'. While modern

Estonian uses -ma as the

ending marking the first infinitive, it

originated from 'a verbal noun in the illative (into)' (J. Aavik).This

ending too would have been in common use, so there would have been an

ancestral version that has survived millenia. The MA sound is

reflective, and would suit reference to something here and now.

3.The Inuit -ksaq

as in nuluaksaq 'material for

making a net', strongly resembles the Estonian translative case ending

-ks so that Estonian can say võrkuks

'(to be made) into a net'. The

Inuit additional -aq is a

nominalizer, and Estonian also has -k

as a

nominalizer. The use of KS to represent an end product of some action,

is psychogicallly suitable. This too would have endured for millenia.

4. In Inuit the ending -ttainnaq means 'the same

for' as in uvangattainnaq 'the same (another?)

for me'. In

Estonian/Finnish there is teine/toinen,

meaning 'another, the other'. One may question this one, but it is

recognized that words can reverse meaning. The reversal could arise

from the word being used with a negation element, and eventually the

concept of 'same' developes into 'not the same, another'. It is valid

to see a link to the opposite concept for a word that is the same

in form.

5. In Inuit there is -pallia as in piruqpalliajuq

meaning 'it grows more and more. This compares with Estonian/Finnish

palju/paljon 'much, many'.

Inuit also has the expression pulliqtuq

'he

swells' which compares with Finnish pullistua

'to expand, swell'. The P+vowel form is commonly found in language in

association to expansion, to blowing something up, as in English "ball".

6. In Inuit there is -tit as in takutittara

'I

make him see' which compares with Estonian/Finnish tee/tekee 'make, do'. This is not a good example, but to the Estonian ear it resonates with teeda 'to do'. This one is on the fence unless other evidence can be found.

7. In Inuit there is -ajuk as in tussajuq

meaning

' he sees for a long time' or the similar -gajuk which makes the

meaning 'often'. This compares with Estonian/Finnish aeg/aika meaning

'time'. This pattern has parallels in Algonquian Ojibwa language

(people of the birchbark skin boat)

8. Inuit kina? 'who?' versus Est./Finn. kelle?/kene? stem for 'who?'

9. In Inuit there is suluk 'feather' which

compares with Est./Finn sulg/sulka

'feather'. This is one of the

clearest parallels. This is also an amazing parallel. It suggests that

birds and feathers were very important. Perhaps feathers were a sign of

land nearby. We note that aboriginal peoples liked to wear feathers.

There must have been a major significant to prevent the word being

changed in form or meaning. Furthermore, we will see later that this

word also exists in the Wakashan Kakiutl language. See later.

10. Inuit kanaaq ' lower part of leg' versus

Est./Finn kand/kanta

'heel'. This is a good example of the word form and meaning being very

close. The lower part of a leg is in deed the heel. The

Estonian/Finnish version is a little more focussed towards the heel. I

would not debate this one more. But see next.

11. Inuit kingmik 'heel' versus Est./Finn king/kenkä 'shoe'

Here the word for 'heel' resonates with the Est/Finn word for 'shoe'. A

shoe is a covering for the heel. Difficult to debate this one.

12. Inuit nirijuq 'he eats' versus Estonian närib 'he chews' This one can be debated, because ninjuq omits the R sound. Why not compare it to Estonian nina 'nose'

('nose in food'?) This one needs more information, from within the

language, derivative words, associated concepts. We need not leave any

hypothesis because the connection is not obvious.

13. Inuit saluktuq 'thin' versus Est./Finn. sale/solakka

'thin' The Inuit stem is SALU which certainly resonates with the

Est./Finn. This is a good one, as it is a concept used every day. There

is always something that is thin. We may wonder if there is a

connection to 'feather'. I would not be inclined to debate this one.

14. Inuit katak 'entrance' versus Est./Finn. katte/katte

'covering'. This too is very believable. The Inuit building had

entrances covered with a skin, thus if it began in the meaning

'covering', it acquired the meaning of 'entrance'. This was especially

true of winter during which people lived in large snow houses, where

the only covering was at the entrance.

15. Inuit ajakpaa 'he pushes it back' versus

Est./Finn. ajab/ajaa

'he

pushes, shoves (it)' This seems obvious too. It is obviously a

common everyday word that is likely to survive for hundreds of

generations.

16. Inuit kina? 'who?' versus Est./Finn. kelle?/kene?

stem for 'who?' This can be debated on the exact forms, but in general

what we see is the use of the K for interrogative pronouns. See the

next. What we are are noting here is this use of the K.

17. Inuit kikkut?

plural 'who?' versus

Finnish ketkä plural 'who?'

(Estonian uses the singular for plural)

18. Inuit kinngaq

'mountain' versus Est./Finn. küngas/kunnas

'hill, hillock, mound' The form is not close, and this comparison can

be debated. We need further evidence for this pair. At least

there is a general parallelism both in word structure and meaning. It

could have experienced some shifting in form and meaning, but the

shifting is not so much as to completely break those apparent parallels

19. Inuit iqaluk 'fish' versus

Est./Finn. kala/kala

'fish'. This can provoke major disageement. However, all we need

for a closer parallel in form is to have the intial "I" in iqaluk to be

dropped, because then we have QALU- It is because of this, that I

accepted this paring. But ideally we need to present an argument that

support the dropping of the "I" is it possible that in FInnic the word

was once IKALA. On the other hand, the Kalapuyan and Karok

languages do not show an initial 'I'. Kalapuyan said K'AWAN (Y)

'fish' and Karok sais 'AAMA for 'salmon. K'AWAN certainly could be

developed from KALA, while Karok 'AAMA seems if is based on another

word. It is possible the ancient oceanic peoples did not give a single

name to fish, but had specific words for different kinds of fish.

20. Inuit tuqujuq 'he dies' versus Est. tukkub

'he dozes'. The Estonian word is a colloquial word, that may have

survived because it come into such common use, while the word for 'he

dies' took another turn (sureb, which has connotations of being driven to the ground, while tukkub has connotations of sleep, the eternal sleep)

22. Inuit iluaqtuq

'suitable comfortable' versus Est./Finn. ilu/ilo

'beauty joy delight'. I paired up there words on account of

ILU. The form is exact, while the meaning is slightly shifted - the

Inuit highlighting comfort, while the Finnic highlighting a state

of joy, beauty. The latter is only a slight exaggeration of the former

and is an acceptable shift.

23. Inuit akaujuq

is another word for 'suitable, comfortabe'

and might be reflected in Est./Finn. kaunis/kaunis

'beautiful, handsome'. In this case there may be some who would debate

this because of the form, AKAU- does not exactly match KAUNI-. I agree

that there may be reason to reject this were it not for the parallels

with the ILU- pairing. Perhaps there is supportive evidence in other

words, where we might find something close to KAUNI-

24. Inuit angunasuktuq

'he hunts' or anguvaa 'he

catches it' compares with Est./Finn öngitseb/onkia

'he fishes, angles'

or hangib/hankkia

'he

procures, provides'. The liking of hunting to fishing is not a problem

because seagoing people hunting was identical to fishing. I find this

paring is easy to argue and that more supportive evidence is available.

25. Inuit nauliktuq

'he harpoons' versus

Estonian/Finnish naelutab/naulitaa

'he nails'. But closer to the

concept of harpoon is nool/nuoli meaning

'arrow'. (Some words

here have echoes with English words - like to nail - because English

contains a portion of words inherited from native British language

which was part of the sea-going people identifiable with the original

Picts. Some also have echoes with Basque which also has connections

with ancient Atlantic sea-peoples) We will refer to harpooning further later, as we find the same word in the Kwakiutl language!

26. Another word of great antiquity in Inuit

is

kaivuut 'borer' which

compares with Est./Finn. kaev/kaivo

'something

dug out' today commony applied to a hole dug out of ground. This

is very close, especially between Inuit and FInnic

27. Inuit qaqqiq

'community house' versus Estonian/Finnish kogu/koko

'the whole, the gathering'. This pair too, matches in form. The

concept of 'community house' and 'gathering' are identical, other than

an indication of a building. The shift that added the concept of a

building could have arisen from the fact that in the arctic, community

gatherings tended to be in the interior of buildings, and not in some

open air location.

28.Inuit alliaq

'branches mattress'

compares with Est./Finn. alus/alus

'foundation, base, mattress, etc' This pairing too makes sense.

All that differs is the reference to the matress being made of

branches. How far in the past has it been since Finnic peoples slept on

branches matresses?!

29. Inuit ataata 'father' compares with

Estonian taat/

'old man,

father' This is a simple term that is found in many languages,

and is similar to PAPA. It is natural, and probably does not need to be

inherited through time.

30. Words for family relations are words not

easily removed, and Inuit produces more remarkable coincidences: Inuit

ani 'brother of woman',

compares with onu 'uncle' in

Estonian, but in

Finnish eno

means almost exactly as

in Inuit, 'mother's brother'. When we consider that over

millenia, these slight shifts in meaning can be expected, these parings

with Finnic words do not need to be debated.

31. Inuit akka

refers to the 'paternal uncle'. In

this case Estonian uses onu

again, but Finnish says sekä

'paternal

uncle' which is closer. See later also ukko.

This is a subject that can be discussed with reference to concepts of

relationships in the societies concerned. But it is clear there are

connections, since if we used a control language we would not see any

of this to arouse even a debate.

32. A most interesting Inuit word is saki meaning

'father, mother, uncle or aunt-in-law'. In Estonian and Finnish sugu/suku

means 'kin'. The Inuit word meaning suggests an institutional

social unit consisting of the head of a family being one's father and

his brother, plus both their wives (our mother and aunt-in-law) As I

wrote above, Inuit culture was based in hunting, and the male who

hunted ruled the society. The brother was both the assistance to

hunting, and the substitute if the other became incapacitated. The loss

of the hunter, cold spell the end of the whole family dependent on

them. This may have been the original meaning of sugu/suku,

but that when the Finnic people left the hunting way of life millenia

ago, the meaning became blurred and generalized, in much the same way

we see above the Finnish eno means 'mother's brother' while Estonian has narrowed it in onu to just 'uncle'

33. In Inuit, paa means 'opening'. This compares

with Estonian poeb 'he crawls

through'. The stem is used in

Est/Finn poegima/poikia 'to bring forth

young', and is commony used in

poeg/poika meaning 'son',

'boy'; but its true nature is actually

genderless. This interpretation can be supported with more evidence.

Even the use of P+vowel for the concept of swelling seems to support an

ancient meaning that was connected to childbirth producing a "POEG" who

crawls out through the opening. Often the support for a pairing comes

from associated words with similar basic elements.

34. Inuit isiqpuq

'he comes in' is interesting in

that it shows the use of the S sound in concepts of 'inside' which is

common in Estonian and Finnish, as in sisu/sisu

'interior' or various

case endings and suffixes. In this pairing it seems in frequent use, the Inuit lost its initial S.

35. Another very basic concept might be seen in Inuit

akuni 'for a long time', as it

relates to Est./Finn. aeg/aika

'time',

kuna/kun 'while', and kuni/--- 'until'.. Some may question this one because the Inuit word, akuni, doesn't exactly match aika or kun; but

all relate to time. This could benefit from further evidence and

discussion. Included in the discussion would be similar patterns found

in the Algonquian language that appear to link to the idea of time. See

the discussions about the Algonquian language below.

36. Inuit unnuaq 'night' compares with

Est./Finn. uni/uni 'sleep'.

Here there is lack of parallelism between 'night' and 'sleep', however

it is possible that the parallelism would be valid if originally the

night was seen as the day being asleep. For an animistic worldview, the

day can be viewed as a living entity that goes to sleep. While we

cannot know for sure, the probability if high that this pairing of

words is valid.

37. Inuit sila

means 'weather, atmosphere', and

compares with Est. Finn. through sild/silta

'bridge, arc' if we use the

ancient concept of the arc of the sky. Of course there will be those

who will want to debate this. The answer will come from an

investigation to see if in traditonal Inuit culture and Finnic culture,

the sky above was considered to be an arc. Another perspective is to

compare sila 'weather, atmosphere' with Est./Finn. ilm/ilma which has exactly the meaning of Inuit sila

- 'weather, atmosphere'. Both concepts could be valid, since in the

development of words in languages, often one word is used for two

meanings through some small change. I believe there is enough here to

proceed to a convincing argument in favour.

38. The Inuit aqqunaq 'storm' is reminiscent of

the earlier word akka for

paternal uncle. It may imply that the storm

was considered a brother of the Creator. The word compares to the

Finnic storm god Ukko. In

Finnish ukko also means 'old

man'. Inuit also

has aggu 'wind side', which

implies the side facing the storm. In

Estonian/Finnish kagu/kaako

means 'south-east'. Prevailing winds

travelled from the north-west to the south-east; thus the word may

originate in a relationship to wind. Looking at all the evidence as a whole, the probability is very high, that Inuit aqqunaq is indeed mirrored in the Finnic words. I believe that if this is investigated further, the evidence will get better not worse.

39. Inuit puvak

'lung' connects well with Estonian

puhu 'blow'. Finnish has

developed the word to mean 'speak'. Later, the selected Kalapyan

words include PUU£ for

'blow'. There may be sound-psychology involved but in my opinion

something like these existed in the original parent language of the

boat peoples. If this is debated, I believe the side in favour will

tend to win.

40. The Inuit nui(sa)juq

'it is visible' may have

a connection with Estonian/Finnish näeb/näkee

'he sees'. In modern

Estonian, the concept of 'visible' could be expressed by näedav.

Algonquian Ojibwa has a similar word. The general form is N+long

vowel and it could be sound-psychological. This one could be debated,

and other evidence would be helpful, to confirm this pairing.

41. Inuit uunaqtuq

'burning' relates to Est/Finn.

kuum/kuuma 'hot' but most

strongly to Finnish uuni

'oven'. This Inuit word obviously matches the Finnic uuni, very

closely. Even though the Finnish word means 'oven', in a world that did

not have ovens, it would have meant 'heating' which is caused by

'burning'. The conceptual connections are very close. In early

languages there were fewer words, and the precise meaning was inferred

from the context in which it was used. Over the last ,millenia the

number of words multiplied mainly because language was increasingly

used in situations where it was not being spoken directly in context,

and therefore words had to present more precise meanings. Thus it is

valid to imagine an original UUN+vowel word that had many

meanings, but all related to the production of heat, warmth.

42. Inuit kiinaq

means 'edge of knife'. This compares with Est./Finn küün/kynsi 'fingernail'

Both the Inuit and Finnic words describe the same type of object - a

thin blade with a narrow edge, It is possible in prehistoric

times the creation of a blade from flint, was seen as the creation of a

tool that was like a large fingernail. And then with the development of

metallurgy and metal knives the word was carried over into knives. I

have not problem with making this pairing.

43. Inuit aklunaaq 'thong, rope' compares

with Est./Finn. lõng/lanka

'thread'. While the Inuit word has the AK at front, everything else

with the pairing works. Note that in primitive times there probably did

not exist a word for 'thread' because a 'thread' would have been seen

as a very thin thong. When skin clothing or boat coverings were sewn

together, the thickness of the 'thread' used would vary greatly. There

was no basis for making a distinction between a 'thread' and a 'thong,

thin rope'. I am happy with this paring, although there is room

still for wondering about the AK- in front. Is it a prefix giving an

additional description to the thin rope? Was the original Est/Finn word

AKLANKA? But I don't think answering this question will

significantly alter this result.

44. Inuit words sivuniq

'the fore-part' compares

exactly with Finnish sivu

'side, page'. But also Inuit sivulliq

'past',

compares with the alternative Finnish use of sivu

in the meaning 'by,

past'. This kind of parallelism in two meanings, is powerful in

arguing a connection since it is not likely to occur by random chance.

In my opinion there is no debate about this pairing. It is interesting

to note that in these parallels, the Finnish word is closer to the

Inuit. This is to be expected since Finnish was located closer to the

northern regions around the White Sea, where our boat-people theory

suggests, the expansion of skin boat peoples began.

45.The Inuit kangia

'butt-end' compares with

Est./Finn. kang/kanki 'lever,

bar' or kange/kankea

'strong,

intense' Here is another example of the Est./Finn. words having

more than one modern meaning. The 'butt-end' is the 'tail end',

the non-business end. The business end of a lever, bar, is the end that

is put under the object being leveraged. In a lever, the tail end is

easy to move. The business end is magnified and strong. It makes sense

that kange/kankea

would mean 'strong,

intense'. I think it is not difficult to connect the concept

of the 'butt-end' as the 'strong end'. I do not think there is a

debate possible that can defeat this pairing.

46. Inuit uses pi to mean 'thing', which has no

parallel to Est. /Finn., however other words with PI show interesting

parallels: Inuit pitalik means

'he has, there is' which may compare

with Est./Finn. pidada/pitää

meaning either 'to hold' or 'to have to'.

Inuit uses piji for 'worker'

and pijariaquqpuq means 'he

must do it'. This is like Estonian pea

'must' To be a worker means to do something that must be done, as

opposed to in leisure one does not have to do what they are doing. Also

pivittuq means 'he keeps

trying but is unable to', which resembles

Est./Finn. püüab/pyytää

'he

tries, he entreats'. I see in this an entire system around P+vowel

words that are associated with the 'work' of hunting in prehistoric

times.

47. In Inuit traditions and indeed throughout

the

northern hunter peoples, the man was always the hunter. This is

reflected in Inuit ANG- words. We have already noted anguvaa 'he

catches it'. There is also angunasuktuk

'he hunts', which is obviously

related to anguti 'man,

male', and angakkuq 'shaman'.

Estonian

kangelane, 'hero', but

literally 'person of the land-of-strong' may

have a relationship to the concept of 'shaman', and also to the earlier

Inuit concept within kangia

mentioned above. In general we see here another example of an

intense focus on hunting in both sea and land, and how hunting skills

were greatly valued. Much could be written on this subject when we

consider the way of life of the prehistoric boat peoples.

48. Inuit also has several KALI words that have

Estonian/Finnish correspondences. Inuit qulliq 'the highest'

corresponds with Est/Finn. küll/kyllä

'enough, plenty'; Inuit kallu

'thunder' corresponds with Est/Finn kalla/--- 'pour;; Inuit qalirusiq 'hill'

resembles Est./Finn. kalju/kallio

'cliff'. In general it looks like there are many dimensions to the KALI words, and it occurs both in Inuit and Finnic.

As I said at the start, I have not arranged these

words in any special order, but the next few words deserve special

attention as they make references to the sea, and how the prehistoric

worldview appears to view the sea as a mother.

49. Inuit has amauraq for 'great grandmother' a

word that might reate to Inuit maniraq

'flat land' . These two words

relate to Estonian/Finnish ema /

emän- 'mother/lady-' on the one hand,

and maa/maa 'land, earth,

country' on the other. As I discuss

elsewhere, early peoples saw the world as a great sea with lands in it

like islands, thus the original concept of a World Mother was that she

was primarily a sea. Thus the original word among the boat peoples

for both World Plane and World Mother was AMA. The meaning of AMA did

not specify land or sea. The proof of this concept seems to be found in

Inuit maniraq since it

contains the concept of 'flat', as well as in

Inuit imaq 'expanse of sea'

which expresses the concept of 'expanse'.

Estonian too provides evidence that the original meaning of AMA was

that of an 'expanse', the World Plane. For example there is in Estonian

the simple word lame

("lah-meh") means 'wide, spread out'. There are other uses of AMA which refer to a wide expanse of sea. One

manifestation of the word is HAMA, as in Hama/burg the original form of

Hamburg . Also there is Häme, coastal province of Finland, etc. which

appears to have had the meaning of 'sea region'. Historically,

according to Pliny, the Gulf of Finland was once AMALA, since he wrote

that Amalachian meant 'frozen

sea' (AMALA-JÄÄN). The words for 'sea' in

a number of modern languages, of the form mare, mor, mer, meri can be

seen to originate from AMA-RA 'travel-way of the world-plane'. The

equating of sea with 'mother' interestingly survives also in French in

the closeness of mère

'mother' to mer

'sea'. The

intention of this

discussion is to show that the worldview appears to be a deep one,

possibly being born when boat peoples expanded into the open sea some

10,000 years ago,

50. However, we must also note that while

Inuit

'great grandmother' is amauraq,

the actual Inuit word for 'mother' is

anaana Is it possible Inuit

used N to distinguish between the sea-plane

and land-plane. Indeed their word for 'land, earth, country' too

introduces the N -- nuna. Or

perhaps the N is borrowed from the concept

of femininity because we also find Inuit ningiuq 'old woman' and

najjijuq 'she is pregnant'

which relate to Estonian/Finnish stem

nais-/nais meaning 'pertaining

to woman'. It is worth noting that we find a similar word in Algonquian

Ojibwa, notably I bring the passage from later into this

paragraph "Another Ojibwa word element with coincidences in both Inuit

and Estonian/Finnish is -nozhae- 'female'. We recall Inuit ningiuq 'old woman' and najjijuq 'she is pregnant'. These compare with Estonian/Finnish stem nais-/nais- meaning 'pertaining to woman, female-'. The Ojibwa nozhae is very close to Estonian/Finnish nais-/nais-, and with exactly the same meaning. Estonian says naine for 'woman', genitive form being naise

'of the woman'" Such connections with Inuit help support my

theory that the Algonquian languages descended from earlier skin boat

peoples established in the northeast arctic of North America, perhaps

the "Dorset" culture ot their ancestral culture.

51. Inuit also says amaamak for 'breast'

which compares to Estonian/ Finnish amm/imettäja

for '(wet) nurse'.

There is aso Est./Finn. imema/imeä

'to suck'. These coincidences are strong indications of prehistoric

connections, and I don't think a debate about this pairing can be

defeated.

52. But, the words which are of greatest

interest are words for 'water'. If there is anything that all the boat

people have in common is the act of gliding, floating, on water.

It appears that in Inuit the applicable

pattern is UI- or UJ- same as in Estonian/Finnish. uj-, ui-, Inuit

uijjaqtuq means 'water spins'

whose stem compares with Estonian/Finnish

ujuda/uida 'to swim, float'.

Interestingly Inuit uimajuq

means

'dissipated', but Estonian too has something similar in uimane 'dazed'

, demonstrating that both use the concept of 'swimming' in an abstract

way as well. (Indeed the concept at least survives in English in the

phrase "his head swims" to mean being 'dazed'.) Considering the Inuit

infix -ma- meaning 'in a

situation, state', it seems that the stem in

both Inuit and Estonian cases is UI, and that -MA- adds the concept of

being in a state, situation.

53. Other notable words might include Inuit umiaq

'boat'. Given what we have discovered so far. the Inuit UMI, might be a rearrangement of UIM- There is also Inuit has umiirijuq

'he puts it in the water'. On the other hand UMI- could have arisen from AMA for sea. Perhaps this is inconclusive. umiaq could mean either something of the sea or something that swims, floats. Either way, there is a connection

54. The most interesting Inuit words to me, are

tuurnaq 'a spirit' and tarniq 'the soul', because they

compare with the

name of the Creator across the Finno-Ugric world. It appears in Finnish

and Estonian mythology as Tuuri,

Taara, etc. And the Khanti

still

concieve of "Toorum".

The

presence of the pattern in Inuit is proof

that it has nothing to do with the Norse "Thor", but that "Thor" is

obviously an adoption by Germanic settlers into Scandinavia of the

original indigenous high god. Norse mythology imported into

Scandinavia some Germanic mythology, but once there among the

indigenous people, their mythology drew into it the indigenous deities,

GRAMMAR: In addition to many basic words, such

as given

above, there are similarities between Finnic and Inuit grammar. The

most noticable is the use

of -T as a plural marker, or -K- to

mark the dual. (Although neither Finnish nor Estonian retains

declension of a dual person, it is easily achieved by adding -ga

'with' into the declension, which is the Estonian commitative case

ending.)

It is not the intention here to do an exhaustive

study of Inuit words and grammar, compared to Finnic words and grammar.

Our intent is to demonstrate an adequate number of comparisons to make

a case that the seagoing and whale hunting peoples that expanded to the

North American arctic are one of the peoples who evolved from the

expansion of a branch of the "Kunda" culture into the northern oceans.

Obviously, these people had contacts with indigenous

peoples, such as caribou (N,A, reindeer) peoples, both linguistically

and genetically and we must expect it. But in my overall opinion the

Inuit language has a fundamental form that suggest the same origins as

the Finnic languages. This is an intuitive judgement, compared to my

intuitve response to the Algonquian Ojibwa (Anishnabe) language which

seems quite foreign to my Estonian ears, in spite of significant word

parallels. For that reason I believe the Algonquian languages primarily

influenced existing indigenous woodland peoples, with the indigenous

language slightly holding the upper hand. We will look at Algonquian

next.

2.

Basques as Possible Descendants of Ancient Whalers

The only surviving peoples of the east Atlantic coast that could be

descended from whaling people and who have managed to preserve their

language are the Basques, described earlier. While scholars do not

consider Basque to be related to any other language, and have failed to

link it to Finnic, the reason is that if we remove the obvlous

borrowings from Latin from Roman times or later, a large number of the

remaining words DO have Estonian parallels (I did not consult Finnish

in this investigation)

The results are just as good as our comparisons with Inuit and other

whaling peoples languages covered in this article focussing on the

languages. The proportion of words that have believable matches in

Estonians, are far better than random chance

. I found the source of

Basque words on a website that presented about 1000 most used Basque

words. I found that the majority of Basque words were

obviously Basque versions of Romance names, borrowed from many

centuries of influence from Romans and then French and Spanish. Thus if

we eliminate the Romance words, we greatly reduce the number of usable

Basque words.

From this limited word list I found a rate of

coincidence with Estonian that is much greater than random

chance.

One has to recognize that the Basque words have to not only

resemble Estonian words but the meanings have to resemble each other

too. Even when the list is limited to the most believable pairings, the

number is remarkably high given that after we removed all that

Latin-based borrowings, there were maybe only 500 source words.

The remarkable parallels between Basque and

Estonian include the following:

1. Basque su

'fire',

compared to Estonian süsi

'coal, ember', süüta 'fire

up';

2.Basque oroi

'thought' compared to Estonian aru

'understanding';

3. Basque ama

'mother'

compared to Estonian ema

'mother';

4. Basque uste

'believe' compared to

Estonian usk 'belief', usu 'believe';

5. Basque ola 'place' vs Estonian

ala 'field (of endeavour)';

6. Basque kale 'street' vs

Estonian kald

'bank, shore' (ie original streets of boat people were rivers, shores);

7. Basque ke 'smoke' vs Estonian

kee 'boil';

8. Basque leku 'space' vs

Estonian lage 'wide open

(place)';

9. Basque hartu 'take'

vs

Estonian haara 'grab hold';

10. Basque ohar 'warning' vs

Estonian oht

'danger';

11. Basque tira

'pull' vs Estonian tiri 'pull

away, pull loose';

12. Basque gela 'room' vs

Estonian küla 'living place,

abode, settlement';

13. Basque lo 'sleeping' vs

Estonian lÄbeb looja '(it,

like the sun) sets,

goes down, goes to sleep';

14. Basque marrubi

'strawberry' vs Estonian mari

'berry';

15. Basque txotx

'twig' vs Estonian oks

'branch''; Basque ohe

'bed' vs Estonian ase 'bed';

16. Basque osatu 'complete' vs

Estonian osata

'without any part'';

17. Basque or, zakur

'dog' vs Estonian koer 'dog';

18. Basque jan 'eat' vs Estonian jÄnu 'thirst';

19. Basque jarraitu 'continue'

or jarri 'become' vs Estonian

jÄrg 'continuation', jÄrel 'remaining,

to-come', etc;

20. Basque giza

'human' vs Estonian keha

'body';

21.Basque

haragi 'beef/meat' vs Estonian

hÄrg 'ox';

22.Basque izen 'name' vs

Estonian ise(n) 'of

oneself';

23. Basque lau

'straight' vs Estonian laud

'board, table' (ie straight piece of wood);

24. Basque lasai 'calm' vs

Estonian laisk 'lazy' or lase 'let go';

25. Basque ezti 'honey' vs Estonian

mesi 'honey;

Basque is considered to be descended

from the people the Romans generally called Aquitani, located mainly in

the Garonne River water basin as far as the Pyrennes mountains.

Aquitani in fact implies

'water-people' in Latin. The name may have been inspired by

Uituriges or Uitoriges ( Caesar Gallic Wars, I,

18) the name of a

people who controlled Burdigala

the town on the lagoon formed by the

outlets of the Garonne River. The word Uituriges or Uitoriges resembles

Estonian/Finnish because the the first part corresponds well with UI-

words meaning basically 'swim', such as Estonian uju, Finnish

uida. The latter part of

Uituriges, is the word meaning

'nation'

(as in Estonian riik, riigi),

hence the name Uituriges

means 'floating

nations'. An alternative name for them in the historical record was

Bituriges. If this was a true

alternative name, then we should look to

BI in the meaning of 'water', and the full word paralleling modern

Estonian Veederiigid, meaning

'water-nations'. This latter version

would be the most applicable inspiration for the Latin Aquitani. I

believe in a pre-literate world where people and places were named by

describing them, that it is possible BOTH versions Uitoriges and

Bituriges were used.

3.

Down into the N.E. Quadrant of North America

Comparing Algonquian Ojibwa with Finnic Languages

THE "INI"

WORDS AND WATER/SEA WORDS

Note: the Northwest Lake Superior dialect is used as it would be least influenced in recent times.

In article/chapter 4, I proposed that the Algonquian

indigenous peoples of the northeast quadrant of North America had

origins in the arctic peoples, such as the "Dorset" or earlier culture,

who arrived in the arctic waters in skin boats around 6,000 years ago

and continued an established life of hunting whales, seals and walrus.

They would have spoken a prehistoric Finnic language, according to the

likelihood that the expanding oceanic peoples had an origin in the

northern part of what is now Finland. When a group had arrived in the

eastern Canadian arctic,they of course found the waters uninhabited,

since boats as part of a way of life had not yet developed in North

America. However, there would have been pedestrian hunting peoples

towards the south, perhaps in what is now Labrador and northern

Quebec. Contact with these people may have influenced the

language a little. But when some of the arctic skin boat peoples

ventured further south either from Hudson Bay, or south along the

Labrador coast, they would have also encountered indigenous woodland

hunters - pedestrian too, and avoiding post-glacial flooded lands. In

any case, the resulting languages were those called "Algonquian:" by

linguists today, and their basic form was that of the original

indigenous people, but heavily modified by the boat people from the

arctic, who would have intermarried with the indigenous peoples, and

both introduced a boat-oriented way of life, and had a significant

influence on language. That is my theory to explain the results of my

investigation of Algonquian languages, selecting the Ojibwa (Anishnabe)

of northern Lake Superior as the subject. The reader is welcome to

offer other scenarios, if there is other information available, to

explain they results presented below.

The Algonquians of Quebec and Labrador called

themselves "Innu". There were the Labrador

Innu associated with the

Churchill River, Montagnais Innu

associated with the Saguenay River.

But as we moved west, the names changed a little. The Algonquins of the

Ottawa River valley today call themselves "Iniwesi" which means 'we

people here alone'. The Ojibwa peoples use variations of the word

"Anishnabe" whose meaning is

something more complex than 'the people'.

However all the Algonquins have their word for 'man, person' in a form

similar to inini. Just as I was originally drawn to the Inuit language because the word is plural for 'person' (singular is inuk) so too I was drawn to the name Innu in Labrador and north coast of the Saint Lawrence, and to the word for 'person' inini. I found it a mysterious coincidence that Estonian possesses the word inimene for 'person'. plural inimesed. wherein -mene, -mesed seems to mean 'in the nature of us' or 'INI -in our character'.

In my investigation of a large number of words from

the Ojibwa language I looked for words that might pertain to boat

peoples to see if I could find words and ideas in common with

Finnic boat people traditions. Considering also grammar, the results

looked more like the way of life with boats, along with a good number

of words, had descended south and very substantially impacted the

indigenous peoples - perhaps to the extent of introducing a

boat-oriented way of life in a previously uninhabited

post-glacial lakelands which proved to be successful and expand rapidly

through all the previously occupied lands only usable with the boats,

the birch-bark sking boats.

Whatever the best explanation is, here is the

results of my comparisons with Finnic, which I decided to group

according to subjects most relevant to boat-oriented peoples. For

example we saw in the Inuit language the stem AMA which was similar to

the word for 'mother' (actually the word for 'grandmother') We

will now see that the Ojibwa language had AMA, even though they lived

in inland waters not the sea. Interestingly too, the Algonquian peoples

pictured North America as a large turtle in a sea, a concept that would

only be envisioned by seagoing peoples accustomed to travelling long

distances in the sea. Thus there is linguistic support for the idea

that the Algonquian birch-bark skin boat originated from arctic skin

boat peoples.

1. WATER: THE WATER-BODY: One of the concepts discussed earlier is the use

of the AMA pattern to express 'water' in the sense of an expanse, a

sea. In the discussion of the Inuit language, it appeared it was found

there. Yes, we can find it within Ojibwa. For example 'he surfaces out