PREFACE

Grammar cannot be directly discovered. It is necessary to

include its discovery in the general pursuit of word stems, and

meaningful sentences that agree with the archeological context. It is

only during the discovery of sentences and maintaining a constancy in

word stems, that it is possible to look for the grammatical

endings that function in the same way in all the sentences. It is only

in the final stage that the gaps in terms of grammatical markers get

filled in and we have an organized description. That is the reason I

did not create this description of grammar until the very end.

See “

THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL” for the word stems and translations of the existing sentences on the archeological objects.

They say that the only way to prove that you have discovered a real

language is if you have identified sufficient word stems (lexicon) and

grammar that you can form new sentences that have not existed

before. I have achieved this, as will be clear in some examples

in this paper.

In general, the common public will think that anything to do with

language, including deciphering an unknown language, is a matter of the

science of linguistics; but nothing could be further from the truth.

Linguistics is the science that studies languages. If a language is

unknown or even no longer existing, there is nothing for linguistics to

study. An extinct language is just silence, and an unknown language is

simply noise patterns. Ancient Greeks called people who spoke in a way

they couldn't understand by the word "barbarian".

There is only one way to decipher an unknown language, and that is to

witness it in use. Linguists will try to find an 'informant' - a person

who speaks the unknown language and a known language that the linguist

knows as well. If Venetic had survived until today, then linguists

would have no problem deciphering it. But Venetic is extinct as a

spoken language. It only exists in short sentences written on

archeological objects dug up in northern Italy over the past centuries.

In the past, when unknown inscriptions have been found, scholars have

hoped to find translations of the unknown language in a known ancient

language like ancient Greek, Roman, Phoenician, etc, But none has

been found. Many Etruscan words have been deciphered from some parallel

texts. As for the ancient language of Crete, nobody has cracked that

one at all. As for Venetic, archeology has never found any inscription

with a parallel text in a known language like Latin. As the

region of the Veneti, in the northwest side of the Adriatic Sea became

Romanized, insriptions on cremation urns became slowly Romanized.

Traditional funerary keywords on urns continued to be used, sometimes

abbreviated. The mixture of Venetic and Latin conventions invited some

scholars to assume that Venetic was already a Latinlike language. And

so, the urn inscriptions of the Romanization period were projected into

the past. No matter how much self-deception there was to try to see

Venetic as a Latin-like language, there really was no parallel text in

understandable Latin to be found.

There is only one linguistic method for deciphering an unknown

language. If the unknown language is known to simply be related to a

known language, then the analysts can simply project the known language

onto the unknown. For example Venetic presents the word

.e.go at the beginnings of inscriptions on obelisques marking the location of tombs. It looks like Latin

ego 'I' so IF YOU BELIEVE Venetic is an ancestral language to Latin, then you will project .Latin

ego onto Venetic

.e.go. The absurd result is that all the tomb markers have the deceased declaring their name 'I am

[proper name assumed in the rest of the sentence]' If you assume Venetic is Latin-like Venetic

dona.s.to looks like Latin

donato

'give'. By coincidence the analyst can see a number of sentences that

look like offerings or gifts are being given to a deity named "Reitia".

If the number of sentences is large, then if the hypothesis is false it

will soon be apparent, and the pursuit of trying to project the Latin

onto the Venetic will come to an end, and replaced by another

hypothesis. This had already happened several times. A hypothesis

that Venetic was "Illyrian" preceded the hypothesis that Venetic was an

archaic Latin. (This stage was documented in

LLV

in the 1960's - see Referemces at the end) Since that did not produce

enough results, some Slovenian academics began

to advance the hypothesis that Venetic was an ancient

Slovenian/Slavic. Meanwhile the formal academic world

that had pursued Venetic as an archaic Latin, finally

decided it was simply an unknown ancient Indo-European. (This is the

last stage and was documented in the 1980's in

MLV - see Refences)

In general, the practice of linguistically projecting an ASSUMED known

language onto the Venetic inscriptions, has produced inadequate

results. Sentences are often empty like personal names on tombstones,

or extremely poetic because the literal translation sound absurd.

When I tackled the deciphering problem, I went back to basic principles

and asked what would I do if I came upon a people with an unknown

language somewhere, and they did not know my language. The answer is

obvious: I would learn the language by observing how it was used in

everyday life, infer meanings, and try to join in and be corrected if I

spoke wrong. Could this methodology be applied if the language only

existed on archeological objects? It is possible if you reconstruct the

situations in which the objects were made and used. Today children

learn to read from books with sentences under pictures that describe

what is pictured. It happens that the Venetic archeological objects

include a number of relief images with texts around them that are

obviously captions to what the images show.

Thus the natural way we learn an unknown language is possible if the

analyst actually projects themself into the people and world that

archeology can reconstruct. We infer meanings of words and,

although there are no real speakers to correct us, we are able to

cross-reference out hypotheses with the circumstances surrounding the

same word or grammatical ending in another inscription on another

object.

This methodology too improves the more examples of objects and

inscriptions there are, but it is surprising how far one can get in

this way. This is because after getting some very solid results from

inferring meanings from the archeological context, it is possible to

partially decipher some sentences, it is possible now to additionally

infer meanings for the unknown words, meanings that fill out the

sentences. Of course the inferred meanings have to undergo

cross-checking throughout all locations it appears. Back and

forth, working on the entire body of inscriptions at one, more an more

words are revealed in this way. Inferring meanings when we can produce

partial translations of course requires we have complete sentences so

that we can identify subjects, objects, etc. Because there were less

than 100 complete sentences, inevitably we would find words that became

a problem, but surprisingly, in the end there were only a handful of

sentences that did not get interpreted in some way.

It is possible to argue that Venetic could have been a Finnic language

because it was located at the southern terminus of amber routes,

mentioned already in ancient times, and confirmed by archeology in the

last century. But I did not EVER project any modern Finnic language

like Estonian or Finnish onto the Venetic. I determined it doesn't

really work. The Venetic was as different from Estonian or Finnish as,

say, Danish from Swedish. Some similarities could be detected but it

would certainly be impossible to compare Venetic with any language that

was 2000 years in its future.

However, once I had determined an approximate meaning for a word, the

Venetic word could then be projected into Estonian or Finnish. Since we

were projecting from Venetic into Estonian, the Venetic would be

identifying a true descendant word and all the rest of the thousands of

dictionary words would be invisible to it. Even so, the meaning

in the Venetic ruled, and finding descendant words in Estonian only

served to confirm the meaning, or to narrow down, or refine the

meaning. This helped improve results by maybe 10-20%.

Linguists say that languages do not change at the same rate throughout.

Frequently used words obtain an inertia and are passed down from

generation to generation. The language taught to children tends to

be the same language through a hundred generations. Common

grammar too - such as basic case endings, imperatives, simple present

and past tense - tends to endure longer. This can be seen when

comparing Estonian and Finnish: the basic grammatical endings are the

same, and only the rarer grammatical forms differ. For this reason

linguists look at grammatical structure similarity to find distant

genetic relationships. Theoretically, if Venetic, Estonian and Finnish

are related from having a common ancestor several millenia ago, then

their basic grammar should be similar. I therefore used, in my

description of grammar below, a comparison of Venetic grammar with

Estonian and Finnish grammar, in order to show the parallelism. The

grammar is somewhat limited though, because I only had less than 100

complete sentences to work with. Often used grammatical forms include

the third person imperative, infinitive, partitive, inessive,...You

will see below, that when the Venetic is compared to Estonian and

Finnish, there are gaps. Some of the gaps can be inferred from the

Estonian and Finnish forms.

The proof that the Venetic language has been discovered comes from

rationalizing the grammar to such an extent it is possible to create

new sentences, and from all the translations of the known Venetic

sentences being believable and suitable for the objects and

circumstances in which they were found.

See “

THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL” for a detailed description of the ideal methodology I used, and which eventually revealed the Venetic language was Finnic.

Because in the end, we found that the Venetic language looked

Finnic, I organized my description of Venetic in a form that makes

reference to Finnic languages. Since most readers will know very little

about Finnic language (the best known are Finnish and Estonian), here

is a basic summary of characteristics of Finnic languages in the Introduction..

Finnic languages are NON-Indo-European language, and therefore most

readers of this will be entering foreign territory. Most scholars know

absolutely nothing about Finnic languages, and that is and has been an

obstacle to proper investigation of the Venetic inscriptions. When

Venetic is regarded as Latin-like, or generally Indo-European, then a

million scholars can try to relate to it. But when Venetic is viewed as

NON-Indo-European, the number of scholars both educated and interested

in the subject drops to merely handfuls.

Thus in this section of describing the results of my determinations of

case endings, you have to think in a different way than when thinking

of Indo-European languages.

1. INTRODUCTION TO VENETIC GRAMMAR

1.1 Venetic as a Finnic Language Must Be Viewed Differently

Basically Finnic languages are strong in case endings, and case endings

can be added to case endings. This is a very old manner of constructing

sentences. The only more primitive language forms can be seen in either

ancient Sumerian, or today’s Inuit of arctic North America – where

ideas are formed by combining small syllabic elements. In the

course of the evolution of languages case endings became incorporated

into word stems, and the freedom to play with case endings decreased.

Also modifiers became separate words placed at the front.

There has been a steady conversion of humankind’s language from short

syllabic words freely combined, to today’s large number of independent

words. It can be compared to making soup from raw vegetables compared

to buying ready-made soup in a can. Modern words are the consequence of

the ‘canning and cooking of basic elements’. In Estonian and Finnish it

is possible to see the consituent elements in words. For example

the word

Eestlane, ‘Estonian’ or in Finnish

Eestilainen, is

regarded as a word, but already adds two elements onto the stem

Eesti.

We have

–la meaning ‘place of’ (

Eestla = ‘Estonian place’) and

then

–ane or

–ainen meaning ‘pertaining to, of the character of’

These are not recognized as case endings because they are not freely

added in actual usage, but poetic authors could do so. For example using

puu ‘tree’, one can say

puulane and could use it to

mean ‘animal of the tree’ such

as a squirrel or monkey or even a human who lives in a treehouse.

Today a large number of endings are not regarded as adding case endings

but as ‘derivational suffixes’ I think part of the problem was that

past Finnic linguists did not want to stray too far from the grammar

descriptions of Indo-European languages. There was an inferiority

complex. Estonians and Finns were even self-conscious of their culture

and language having aboriginal origins in the prehistoric canoe-using

hunter-gatherers

Thus, using the above examples,

Eestlane or

puulane are words in

themselves and to this we can add more case endings. We can thus have

Eestlastele from

Eestlane – t – ele ‘to the Estonians’. But from

a more polysynthetic view, we have

Eesti – la – ne – t –

ele A great deal of the Estonian and Finnish words already

contain many of the abovementioned ‘derivational suffixes’ which to a

great extent can be case endings too if an author wants to play with

them.

It shows the progression – that as structures with case endings become

used so often they seem like words in themselves, the constituent case

endings become frozen into them. It is how all the words in all

languages evolved. All that has happened is that some languages

progressed slowly on this path, which other progressed slowly.

From a Finnic perspective, some Venetic words produce revealing results

when broken down into their elements. For example the goddess is

addressed with

$a.i.na te.i. re.i.tiia.i. I interpreted

$a

as the basic stem meaning ‘lord, god’ -

.i.- is a pluralizer, and

–

na is a case ending meaning ‘in the form, nature, of’ The

resulting meaning is to describe the goddess having ‘the character of

gods’. It resonates a bit with Etruscan

eisna ‘divine’ and with

Estonian

issa- ‘lord’ and we can form a parallel

issa-i-na

The intent was to address the goddess in the praiseful way so that the

whole

$a.i.na te.i. re.i.tiia.i. means ‘joining with You,

Rhea, of the nature of the gods’ (‘of the nature of the gods’ can

be stated simply with ‘divine’.)

Words that were difficult to decipher from context, became easy when

broken apart into Finnic-type elements, but often resulted in abstract

ideas whose precise meaning needed some imagining of what went on in

the actual context. For example

V.i.rema.i.stna.i. (

v.i.rema =

v.i.-re-ma and then

v.i.rema - .i. - .s.t - na - .i.) which

is very abstract but because it was used in place of

$a.i.na it

has to be praisful, and so I decided it meant something like ‘uniting

with Rhea in the nature of arising from the land of life energy’.

Similar sentences in the same context plus the context of the sentence,

helped move towards the more precise meaning. Note that ancient

language was always spoken in context, so that the context would help

in making the meaning clearer.

1.2 Some Notes on reading and writing Venetic Inscriptions

Venetic writing was peculiar in that dots were added between

characters, whereas Etruscan and Latin used dots only to mark word

boundaries.

The convention is to write the Venetic text in small case Roman, introducing the dots in the correct places.

|

THE NATURE OF THE VENETIC WRITING.

CONTINUOUS TEXT AND DOTS (FOR MORE DETAIL SEE PART A):

The Venetic inscriptions do

not mark word boundaries. Instead the sentences are written

continuously, and dots are added before and after letters. This practice has puzzled traditional analysts

and had come to be regarded as a ‘syllabic punctuation’, but I

discovered this is incorrect. Venetic writing is pure phonetic writing

with the dots used to mark situations in which the pure sound of the

character is altered by actions of the tongue – mostly palatalization.

If a dot appears before and after a character, the sound of that

character is palatalized. The dots can be thought of as tiny

“I”s. These are phonetic and easy to understand. Writers simply

threw the dots into the script where there was palatalization or some

other effect from the tongue, such as trilling an R, and single dots

could also be used to signal pauses or added length. (A consonant

becomes a pause while a vowel gets added length)

The phonetic marking helps us understand how Venetic was spoken (One

can use highly palatalized Livonian – a Finnic language – as a model

for how to speak Venetic, but also the palatalization survives in

Danish, even though the original Suebic was replaced by Germanic.)

But as far as grammar is concerned, I think the palatalization was

just

a paralinguistic feature, and did not really have to be marked. If

Venetic had been written with dots or spaces separating words, it would

have been fine – except that our ability to understand how it sounded

would be lost. Therefore, the reader of this description of

grammar need not be concerned about the dots too much. Estonian has

weak paltalization which is not explicitly marked, whereas Livonian has

strong palatalization and it is marked. Venetic probably does not need

to mark the palatalization, and it exists only to reproduce the actual

sound when word boundaries are not shown. I show the dots anyway

in

order to remain true to the original Venetic writing.

For a detailed discussion of the dots, see the main document, or my

separate paper on the dots. (See references for "How Venetic Sounded")

NOTE : In

the following examples of Venetic texts, we represent the character

that looks like an M in the Venetic alphabet with the keyboard

character $ but we interpret the sound as "ISS" as in

English "hiss", whereas the s with the dots is palatalized and sounds like "sh"

|

1.3 Finnic Grammatical Features to Find in Venetic

The following presents the main characteristics of Finnic found in

Estonian and Finnish. We bear these in mind in order to be on the

lookout for these characteristics in Venetic.

MANY CASE ENDINGS/SUFFIXES, ADDED AGGLUTINATVELY.

Venetic as a Finnic language would be agglutinative.

That means case endings (or suffixes), can be added to case endings to

express complex thoughts. This is actually a degeneration of the

most primitive forms of language which have a relatively small number

of stems, and an abundance of suffixes, affixes and prefixes. Linguists

call a language that is extremely of this nature ‘polysynthetic’ .The

Inuit language is a good example. There are indications in some Inuit

words and grammar that it has the same ancestor as Finnic

languages. Finnic languages are best understood if they are seen

as having such a ‘polysynthetic’ foundation, and then being influenced

towards the form of language seen in Indo-European.

(It is important to note that the modern descriptions of Finnic

languages like Estonian and Finnish are somewhat contrived in that they

modeled themselves after grammatical description models similar to what

had already been done in other European languages. The reality is that

Estonian or Finnish case endings are merely selections of the most

common endings from a large array of possible suffixes. Thus even

though in the following pages we are oriented to specific formalized

case endings in Estonian and Finnish, there remains also suffixes that

could have been described as case endings if the linguist who developed the popular

grammatical descriptions had chosen to. The difference between

‘derivational suffixes’ and ‘case endings’ is merely in the latter

being commonly applied in the opinion of the linguists who described

the grammar.)

PREPOSITIONS, PRE-MODIFIERS, CASE ENDINGS & SUFFIX MODIFIERS

It seems as if in the evolution of language, the ‘polysynthetic’

form degenerated in the direction of our familiar modern European

languages, where there are less and less case endings, and more and

more independent modifiers located in front. But Finnic languages are not

as ‘primitive’ as Inuit, and have developed through millennia of being

influenced from the languages of the farmers and civilizations - some

premodifiers, adjectives, prepositions and other features placed in

front. Venetic, like modern Finnic, present some instances of

prepositions and pre-modifiers, like

va.n.t.- and

bo-

but in general there are very few modifiers in front. It appears that

instead of adjectives, Venetic liked to create compound words, where

the first part – a pure stem without case endings – was somewhat

adjectival.

NO GENDER. NO GENDER MARKERS ON NOUNS

There is no gender in Finnic languages. There is no ‘la’ or ‘le’ in

front, nor any gender marker at the end. English too lacks gender in

nouns, so that will not be a problem for English readers here.

But there is only one pronoun in Finnic for ‘he,she, it’. In Venetic we

do not mistakenedly consider some repeated ending to be a gender

marker, but look for a case ending or suffix.

NO ARTICLES. USE PARTITIVE INSTEAD OF INDEFINITE ARTICLE

In English and many European Indo-European languages, there are

definite and indefinite articles. For example French has un or

une as the indefinite article and le or la as the definite article.

Finnic does not have it. Instead the indefinite sense as in ‘a’ or

‘some’ is expressed via the Partitive. The Partitive is a case

form that views something as being part of something larger. For

example “a” house among many houses. or “some” houses among many houses.

PLURAL MARKED BY T, D or FOR PLURAL STEMS I, J

Plural in Estonian and Finnish is marked by T,D or I,

J added to the stem according to phonetics requirements. Finnish only

uses the T in the Nominative and Accusative, and then uses I, or J to

form the plural stem. Estonian uses T for plural stem, and then

uses I or J if necessary where phonetics calls for it. Venetic

appears to have both plural markers too, but perhaps more like

Estonian. As we will see, there is more reason to attribute

Estonian conventions than Finnish conventions to Venetic. (There is

reason to believe that Estonian and Venetic/Suebic have the same

ancestral language – see later.)

CONSONANT AND VOWEL HARMONY, GRADATION

Venetic shows evidence of consonant gradation and vowel and consonant

harmony. For example if a suffix/ending is added to a stem with high

vowels or soft consonants, the sound of the suffix may be altered to

suit - with a lower vowel going higher, or a soft consonant going

harder. For example

ekupetaris has hard consonants P,T, hence the

K in

eku instead of G as in

.e.g.e.s.t.s. We can find

similar situations with vowels, unforunately the Venetic inscriptions

are phonetic and capture dialectic variations, and the number of

examples is very small.

COMPOUND WORDS –FIRST PART IS STEM, SECOND PART TAKES ENDINGS

A compound word occurs when a word stem is added to the front of

another word stem. The case endings then are added to the combined

word. We can detect them in Venetic when we see a naked word stem in

front of another word stem but the latter taking the case endings.

WORD DEVELOPMENT

Generally all words develop in the following way, but this is less

noticable in the major languages today. Words began with very

short stems with broad, fluid, meanings. As humans evolved, they needed

to name things more specifically, and did so by combining them with

additional elements – suffixes, infixes and prefixes. As the new word

came into common use, the new word would become a stem in itself,

taking its own grammatical endings. Because of abbreviation and

other changes in the stem, the fact that the stem arose from a simpler

stem, becomes obscured. For example in Estonian we might create the

word

puu-la-ne ‘tree-place-pertainingto’ as a poetic word for an animal

who lives in trees. If this word were to come into common use,

such as describing a squirrel, we might have

puulane =’squirrel’ which

then over time might degenerate to

pulan.

Puulane>pulan then

is a stem for endings, such as

pulanest ‘from the

squirrel’. This is invented for illustration, but a real example might

be how the word

vee might have developed into the word for ‘boat’

as follows:

vee (‘water’) >

vee-ne (‘pertaining to water’)

>

vee-ne-s (‘object pertaining to water’) > reducing to

vene

(‘boat’).

(In our analysis of Venetic, we looked into the internal construction of words for insights)

2. VENETIC CASE ENDINGS

2.1 CASE ENDINGS IN GENERAL

2.1.1. Static vs Dynamic Interpretations of Some Case Endings

When one first looks at Venetic the first thing one notices are endings

of the form

-a.i. or

-o.i. or

-e.i. Sometimes there is a double

II in front, as in

-iia.i. A good example is

re.i.tiia.i.

The context of the sentence, even when it was viewed from a Latin

perspective from imagining

dona.s.to was like Latin

donato, is

that it was like a Dative – an offering was being given ‘to’ a

Goddess. This remains true when viewed in our new Finnic perspective -

something is brought ‘to’

Rhea. But is it a Dative? I was fully

prepared to grant that ending,

(vowel).i. , a Dative label,

but the more I studied it wherever it occurred it seemed to most of the

time to have a meaning analogous to how in modern religious sermons, the

priest might say ‘to join God’ or ‘to unite with the holy’ and so on. I

eventually found this idea of 'uniting with' has to be correct because in

the prayers written to the goddess

Rhea at sanctuaries, written in

conjunction with burnt offerings, one is not giving the offering to

Rhea in the manner of a gift, but rather releasing and sending the spirit via the smoke which then joins or unites with

Rhea up in the clouds. Indeed

even in modern religions one does not 'give' something to our high

deity, but sends something to the deity, to be with the deity, to unite

with the deity.

But what was this case ending if it was not Dative? What case ending

would mean ‘uniting with’? But then I saw the ending from time to time

in a context where it seemed to be like a regular Partitive. If a

regular Partitive has a meaning ‘a thing’ or in plural ‘some things’ and can be

described as something ‘being part of’ a larger whole, then if it were

viewed in a dynamic way, would that not mean ‘becoming part of, to

unite with’? If this is the case, then we would have to discover

Venetic having a static vs dynamic interpretation in other case

endings too.

Let us assume the Partitive has two forms – the normal

static form and a dynamic form (‘becoming part of, uniting with,

joining’) Let us investigate.

Overlooking similar endings for the Terminative

-na.i. or used

for the infinitive use of

(vowel).i., which we will discuss later, we can find the example.

lemeto.i. .u.r.kleiio.i. - [funerary urn - MLV-82, LLV-Es81]

‘Warm-feelings. To join the oracle’s eternity’

In this describing of Venetic grammar we will not explain the entire

laborious process of establishing the word stems. That information is

extensively discussed in the main document - “

THE VENETIC

LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL”.

Here the first word, a plural of

leme can only be a static Partitive –

‘Some warm-feelings’, while the second expresses a dynamic Partitive

conveying the sense of ‘towards’ in the sense of ‘joining’ (‘becoming

part of’) an infinite destination, the infinite future with which

the oracle deals with. One may wonder if the double I (

-ii-) is an

infix that makes it dynamic. (See later discussion of the

-ii-)

If it is possible for a language to allow a case ending to be

interpreted in both a dynamic and a static way, what more can we say

about it? What do I mean by dynamic vs static meanings of a case form?

It is not unusual for a word to have a different role in a

different sentence context. An example of dynamic vs static

interpretation can be seen in how English uses

‘in’. One can say “He went

in the house” and it would be clear

the meaning is he went ‘

into’ the house.

But if this variation in meaning depending on the whole sentence

meaning only occurs with the Partitive, then we may wonder if the

hypothesis is correct. But then I found that Venetic

appears to have both dynamic and static ways of interpreting ‘

in’ as

well. The Venetic Inessive (‘

in’) is marked by

.s.

– often the meaning,

as a result of context, ‘into’ not ‘in’ as Inessive requires. The only

difference between the concept ‘in’ and the concept ‘into’ is whether

there is movement. Thus one case can be used for both static and

dynamic intepretations. The correct interpretation is determined from

the context. There is no need to create separate cases for when there

is no movement, vs movement, if it is easy to understand from the

context. It can be argued, then, that case endings originally did not

explicitly make the distinction - except if clarity was needed, an

adverb was added that explicitly meant, for example, 'into' (in

Estonian there is sisse 'into' so one can say 'he went in the house -

into' as in

tema läks majas -sisse' which evolved to

tema läks majasse'.

Modern Finnic languages have developed explicit static vs dynamic

interpretations – perhaps from the development of literature which

promoted more precision. For example modern Finnic will have an

explicit ‘in’ case in the Inessive and an explicit ‘into’ case in

the Illative. But perhaps originally it was not that way. One

indication of it is the fact that, for example, the Estonian and

Finnish Inessive (‘in’) case endings are similar (Finn.

-ssa versus

Est.

–s) and yet the Estonian and Finnish Illative (‘into’) case

endings are different . This suggests that

the Illative case is a more

recent development and they do not have a common parent. The common

parent would have had an Inessive case that could have a dynamic

meaning if the context required it. Then I think the use of the

language – probably about a thousand years ago - put pressure on

being more explicit and that lead to Finnish and Estonian developing an

Illative each in their own separate way. Finnish has an Illative case

(‘into’) that looks like it was developed out of stretching the Genitive (‘of’)

for example Finnish

talo - Genitive

talon, Illative

taloon. Meanwhile

Estonian has an Illative that looks like it was an enhancement from the

original Inessive in that

–s becomes

–sse . Estonian (using

talu) the

Inessive (‘in’)

talus, Illative (‘into’)

talusse.

In summary, it appears that the ancestral language of Estonian and

Finnish only had the Inessive, and that the Illative developed when

Estonian and Finnish had branched away from each other, and perhaps

only less than the last two millenia. In short, the Illatives

being very different, are not related, while Inessives are similar,

hence are related and must have been in the common ancestral language.

If Venetic only has the Inessive for both usages, then Venetic precedes

any development of an explicit Illative.

The development of the Illative described, indicates that they

developed from a lengthening of a static case. This lengthening is a

natural development when we wish to indicate movement. For example,

Estonian Illative -sse can easily arise from the speaker of an

original –s simply lengthening it to emphasize movement, as in talus

> talusse. What is peculiar is that the Finnish Illative was

developed by adding length to the Genitive! It is possible when you

consider that you can start with a Genitive (talon ‘of the house) and

exaggerate it to get the concept of ‘becoming of’ (taloon ‘becoming of

the house’ =‘into the house’) Thus, technically the Estonian Illative

and Finnish Illative have different underlining meanings!

This shows that if originally Finnic had static case endings that would

assume dynamic meanings (from movement) from context, the dynamic forms

could be spontaneously implied by the speaker simply lengthening

it. We take any static case and add into the meaning ‘becoming’

as for example ‘into’ = ‘becoming in’.

Thus if we accept that Venetic cases could be interpreted in both

static and dynamic ways, we have to allow all the static case endings

the possibility of having dynamic meanings.

Returning to the Venetic Partitive. Depending on the context, the

listener would interpret the Partitive ending either in a static way

‘part of a’ or a dynamic way ‘become part of a’ ideally

interpreted in English as ‘unite with, join with’ That is the

reason, I interpret

re.i.tiia.i. with ‘join with

Rhea’ instead of

simply ‘to Rhea’. I believe the intended meaning was that the item

brought to the sanctuary and sent skyward as a burnt offering was

intended to join Rhea, become part of

Rhea – the Partitive case

assuming a dynamic meaning here that had a more complex implication to

it – that of the offering travelling into the sky and joining, uniting

with, becoming part of

Rhea. As I said above, the idea is

reflected in modern religious ideas of ‘uniting with God’.

We have above now identified two Venetic case endings that can be

interpreted either statically or dynamically. (v means ‘vowel’)

-

v.s. can mean either ‘in’ or ‘becoming in’=’into’

-

v.i. can mean either ‘a (part of)’ or ‘becoming part of’ = ‘join, unite with’ and an added

-ii- may emphasize the latter.

I noticed that often the seeming dynamic interpretation of the

Partitive in Venetic is preceeded with the double

ii as in the

example

re.i.tiia.i. This insertion of the long

ii sound may be

an explicit development, analogous in the psychological effect of

lengthening, to how Finnish achieves the Illative meaning by

lengthening the last vowel (example

taloon). It can therefore be

interpreted with its psychological quality. The possibility exists that

the double

ii can serve as an explicit way of making the following

ending dynamic. That is to say perhaps –

iia.i. instead of just –

a.i

emphasizes the fact there is movement. We will consider the –

ii- infix

further later.

The following sections describe case endings, in the order of presence

in the Venetic. The case endings names are inspired by Estonian and Finnish case

ending names. We will reveal examples in the Venetic inscriptions

and note them. However, case endings are really frequently-used

suffixes, and Venetic may have some additional suffixes which could be

considered additional case endings for Venetic. A summary of our

investigation of case endings and comparisons with Estonian and Finnish

case endings will follow this section in the table at the end of

section 2

2.1.2. Introduction to Est./Finn. Case Endings and the Presence of these Case Endings in Venetic.

Since we will structure our description of Venetic case endings in the

standard descriptions used for Estonian and Finnish, and since we will

make comparisons between Venetic and Estonian and Finnish case endings,

we should first summarize the common accepted case endings in Estonian and

Finnish.

The list is oriented to Estonian and the modern order in listing them.

This is by way of summary of the ones we have looked at, showing which

ones do and do not have resonances with Venetic. See also the chart

given in Table 2.

The following is an introductory overview of the possible case endings

based on Estonian and Finnish. This will be followed by more detailed

study of each, and how it is represented in Venetic.

Nominative -- identified by a finalizing

element that has to be softened when made into a stem. Even if the last

letter may be hardened over the stem, there is no formal suffix or case

ending.

Genitive ‘of’ (Estonian)

[stem], (Finnish)

-n

identified by a softened ending able to take case endings Venetic

seems to have gone the direction of Estonian – ie Genitive given by stem

Partitive ‘part of’ (Estonian)

-t (Finnish)

-a Venetic appears to have evolved

to convert the

–t in the parental language of Estonian and

Venetic/Suebic into –

j (

.i.)

Inessive ‘in’ (Est.)

-s (Finn.)

-

ssa Appears in Veneti as

-

.s. but Venetic uses it in both a static way to describe something and

a dynamic way with meaning of Illative ‘into’

Illative ‘into’ (Est.)-

sse

(Finn)-v v

n NOT in Venetic, meaning the

explicit Illative may be a development since Venetic times, as I

described above. Venetic allows –.

s. to assume this dynamic meaning

according to context needs.

Elative ‘out of’ (Est.)

-st, (Finn) -

sta strong in Finnic languages

including Venetic but appearing mainly as a nominalizer and therefore

must be very old

Adessive ‘at (location)’ (Est.)

-l (Finn.)

-lla

Due to similarities between Est. and Finn. versions is another very old

ending, hence expected within Venetic (and is as -

l)

Allative ‘to (location)’ (Est. and Finn.)-

lle Because

it is found in both Est. and Finn. also very old, and we found it in

Venetic as –

le.i..

Ablative ‘from (location) (Est.) -

lt (Finn.) -

lta Probably also in Venetic at least embedded in words like

vo.l.tiio

Translative ‘transform into’ (Est.)-

ks

(Finn.)-

ksi Not identified yet in Venetic, but if it exists in

both Estonian and Finnish one might expect it does exist in Venetic

too. One watches for evidence.

Essive ‘as’ (same in all three languages)-

na

This is one of the endings that must be very old to appear in all three.

Terminative ‘up to, until’ (Est.)-

ni (not

acknowledged in Finnish grammar) This seems it may exist in

Venetic as Essive plus dynamic Partitive -

na.i.

–

ne.i.

Abessive ‘without’ (Est.)

-ta Not noticed in the Venetic, but could be there somewhere.

Comitative ‘with, along with’ (Est) -

ga Venetic

definitely presented

k’ or

ke in the meaning ‘and, also’ as in

Estonian

ka, -

ga. Unclear if it occurs as a suffix in Venetic.

The following go through the above in more detail:

2.1.3. Nominative Case

In Estonian the nominative has a hard ending as it lacks case

ending or suffix. If there is a case ending, there is a stem with a

softened ending since more will be added to it. Common in Estonian is

the softening of a consonant too. For example Nom.

kond, and stem

becomes

konna- Since we find in Venetic -

gonta as well as

-

gonta.i. etc this character of reducing the t to n may not exist in Venetic. I expected in

Venetic too the Nominative may show a harder or more final terminal

sound than when it becomes a stem for endings. It may depend on the

nature of the stem. But in the Venetic inscriptions I simply

looked for the stem without endings and that would then be the

nominative.

It may seem strange, but the appearance of the Nominative in the

Venetic inscriptions is very rare – almost always there was some kind

of ending – because most of the sentences have the following as the

subject (The nominative occurs only as the subject)

dona.s.to ‘the brought-thing’

dona.s.to however contains endings, as the primitive stem is

do- See discussion in section 1.2

Some other Nominatives (underlined)...(Spaces added to show word boundaries)

5.K)

.a.tta ‘the end’ [urn- MLV-99, LLV-Es2]

7.A)

ada.n dona.s.to re.i.tiia.i v.i.etiana .o.tnia -

[MLV-32 LLV-Es51]

Above we see the ending –

ia Such an ending is indicative of the

Nominative. It resembles the –

ia ending used in Latin, but did not come

from Latin since Venetic is older than Latin.

7.B)

v.i.o.u.go.n.ta lemeto.r.na .e.b. - “

The collection of conveyances, as

ingratiation producers, remains”

[MLV-38bis,

LLV-ES-58]

Above we see

v.i.o.u.go.n.ta which is unusual

since this word usually occurs with an ending like

v.i.o.u.go.n.ta.i and hence is usuallly not

nominative.

In general, once you determine the word stem from scanning all words

for the common first portion, you can assume when that word stem occurs

without any such ending, it is Nominative. Later we will see something

similar when studying verbs. When a verb appears not to have any

endings, then we regard it as the common imperative. (See later section

on verbs) For verbs we determine the verb stem by removing the endings

(The present indicative, past participle, infinite, imperative...)

2.1.4. Partitive Case -v.i. ‘part of; becoming part of’

This is the case ending that earlier analysis from

Latin or Indo-European was thought to be “Dative” because by

coincidence the mistakened idea that

dona.s.to was related to Latin

donato, the prayers to the goddess seemed to speak of an offering being

given to the goddess. (In reality nothing was being given directly to

the goddess, but something was being burnt and its spirit was being

sent up to join with the goddess in the clouds, and that needed a

different kind of case ending than simply giving.)

Practically any static case ending could become a dynamic one which can

be interpreted broadly with ‘to’. A good example a Genetive

ending meaning ‘of, possessing’’ in a dynamic sentence with movement

can become ‘becoming possessed by’ as in ‘coming to be of, coming

to possess’ which in a general way can be interpreted as ‘to’ in the

sense that when something is given ‘to’ someone, it is becoming

possessed by them. Similarly giving something ‘to’ someone can also

mean ‘becoming part of’ (from Partitive) or ‘becoming inside’ (from

Inessive, turning into an Illative meaning) or ‘coming to the location

of’ (from Adessive, becoming Allative in meaning). As I said in

2.1.1, I believe that in actual real world use, the dynamic

interpretation was dictated by context. But with the arrival of

literature much context was lost and it was necessary to be more

explicit in terms of whether a meaning was static or dynamic. And

sometimes a meaning could shift. I believe that Finnish Illative ‘into’

developed from its Genetive – that the dynamic Genetive meaning

‘becoming of, becoming possessed by’ came to be used in the sense

of ‘becoming inside’.

Similarly a dynamic Partitive ‘becoming part of, uniting with’ could

shift its meaning towards the Dative idea of giving something ‘to’

someone.

The main reason for my regarding this case ending as a Partitive rather

than another case that will also reduce to a Dative-like ‘to’, is that

in some contexts in the inscriptions it appears in a regular Partitive

fashion much like in Estonian or Finnish. That means that the dynamic

meaning of the ‘to’-concept actually means ‘becoming part of’, or

‘uniting with’, etc.

Comparing with Estonian Partitive. Here is more evidence that

this case ending in Venetic of the form -

v.i. was intrinsically

Partitive: we can demonstrate that the Venetic Partitive can be

achieved if an Estonianlike Partitive (which may have existed a couple

millenia ago in the common language) was spoken in an intensely

palatalized manner. I explain it as follows:

The Partitive in general can be viewed as a plural treated in a

singular way (one item being part of many), and so the plural markers

come into play. The plural markers in Finnic are -T-,-D-, and -I-,-J-;

hence the replacement of T, D with J,I is already intrinsic to Finnic

languages. When speakers of the ancestor to Venetic – Suebic – began to

palatalize a great deal, they found the -J ending more comfortable than

-T.

Estonian marks the Partitive with a -T-,-D- and therefore it isn’t

surprising that you can get a Venetic Partitive by replacing the

-T-,-D- ending with -J-, as in

talut >

taluj (= “

talu.i.”).

While it is possible in this way to arrive at the Venetic Partitive

ending from the Estonian one, one cannot do so from the Finnish

Partitive. This suggests that both the Estonian and Venetic/Suebic

languages had a common parent. Perhaps the Estonian Partitive came

first. Then, with strong palatalization, the Venetic/ Suebic Partitive,

converted the -T-,-D-, to -J (.i.)

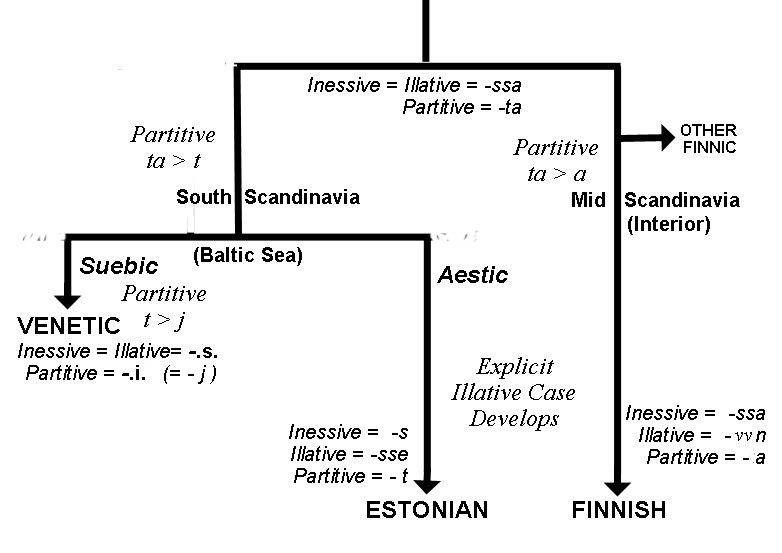

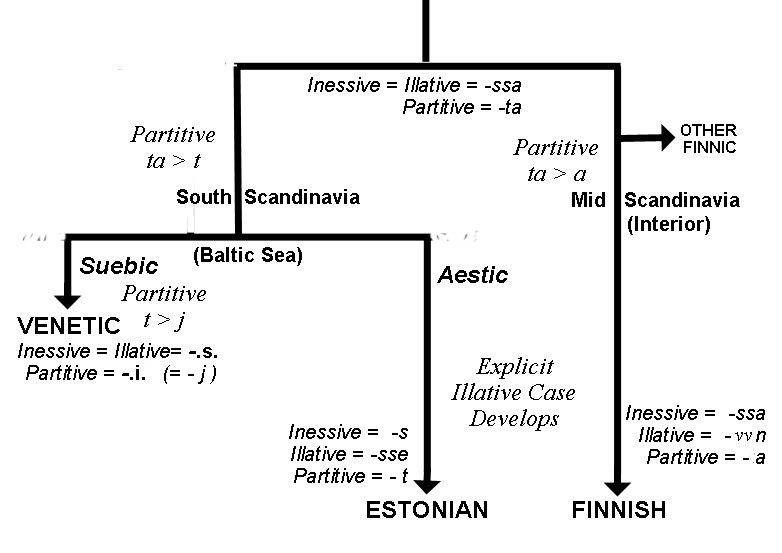

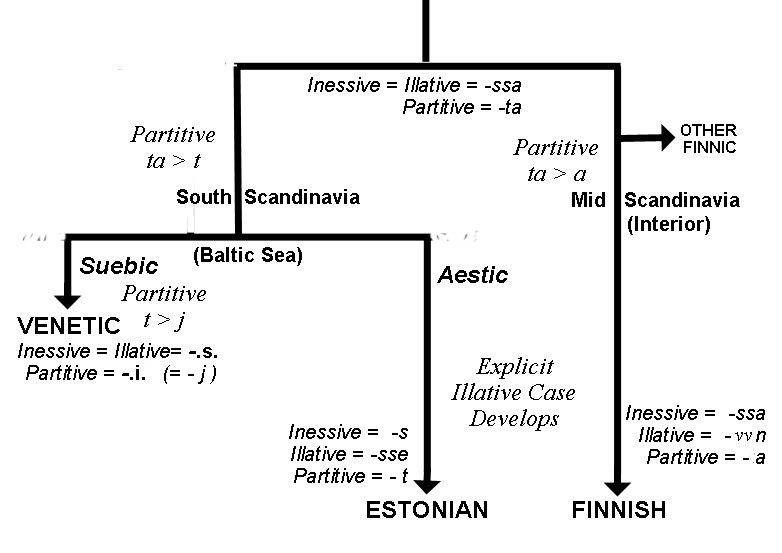

This and observations of the Inessive as well, give us a family tree of

Finnic language descent which agrees with both archeological knowledge

and common sense. I have shown it below in a tree diagram.

In it I show how we can arrive at the Estonian Partitive and modern

Finnish Partitive from an ancient one, and then arrive at the

Suebic/Venetic Partitive from highly palatalized speaking of the

Estonian-like Finnic that was presumably the first language used among

the sea-traders across the northern seas.

Follow the Partitive in the tree chart. We begin with –TA which then loses

the T in the descendants going towards Finnish, and loses the A in the

descendants going towards Aestic and Suebic (as I call the two ancient

dialects of the east and west Baltic Sea). The common

Baltic-Finnic language then on the west side interracts with

“Corded-ware” Indo-European speaking farmers, and becomes a little

degenerated and spoken with a tight mouth that results in intensified

palatalization, rising vowels, and that the –T Partitive is softened to

a frontal H or J sound, which is what the Venetic Partitive ending

-v.i. means.

This chart also describes how the Estonian and Finnish Illatives must

be developments in historic times, as Venetic shows no presence of an

explicit Illative (‘into’) but uses the Inessive (‘in’) in a dynamic

context to express the Illative idea. I show above how the

Estonian Illative developed out of emphasis on the Inessive, while

Finnish derived it from emphasis on the vowel in the Genetive.

See later discussions of the Inessive case in Venetic.

Thus the Venetic Partitive could be interpreted in a static or dynamic way as follows:

Static interpretation (‘part of’): This is the normal use of the

Partitive - where something is part of something larger. It is

indefinite and is equivalent to using the indefinite article “a” in

English. The static Partitive appears a number of times in the body of

Venetic sentences, such as

rako.i.

in

pupone.i. e.go

rako.i. e.kupetaris

but because so many of the

inscriptions are sending offerings to Rhea or a deceased person to

eternity, the following dynamic interpretation tends to dominate. In

other words the prevalence of the dynamic partitive interpretation in

the body of inscriptions is purely the result of archeology finding

mostly funerary inscriptions dealing with sending things to the goddess

or eternity and requiring the dynamic interpretation below.

Dynamic interpretation (‘becoming part of, joining with’): Perhaps

dynamic interpretation was less in everyday use of Venetic, but very

few inscriptions show everyday sentences. If we gave the Partitive a

dynamic meaning, it would be ‘becoming part of many’. The best

concept is ‘to join with’ or ‘unite with’. For example giving an

offering to the Goddess in

re.i.tiia.i does not mean giving

in a give-recieve way, but rather for that offering is to unite

with her, become part of her. It resonates with modern Church

expressions of ‘uniting with God’.

Further Discussion:

From an Estonian point of view, one can understand how there can be a

dynamic interpretation because of the alternative Partitive and

Illative in Estonian , where, using the stem

talu, both the

alternative Illative (a dynamic case meaning ‘into’) and alternative

Partitive have the same form

tal’lu based on lengthening. This

suggests that the language from which this alternative form came must

have had a dynamic Partitive interpretation like we see in Venetic, and

its usage was so much like a newly created Illative that it was linked

to the Illative. In that case the so-called Estonian alternative

Illative is not an Illative at all, but a dynamic interpretation of the

Partitive. Sometimes the only indication of the alternative Partitive

in Estonian is emphasis or length. But this only underscores the fact

that explicit dynamic case endings can easily shift their meaning.

One of the sentences discussed in

THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL was..

(a)

.e..i.k. go.l.tan o.s.dot olo.u. dera.i. kane.i - [container - MLV- 242, LLV- Ca4]

Here we see

dera.i. kane.i ‘a whole container’ in the static Partitive

interpretation. In Estonian the normal Partitive is to use -T-,-D-

instead of the J (

.i.) as in Est.

tervet kannut but it is also common

to say in Estonian

terv’e kann’u adding length. Considering that

Estonian was converged from various east Baltic dialects, in my opinion

this alternative Partitive form in Estonian comes from ancient Suebic

(the parent of Venetic) from the significant immigration from the west

Baltic to the east during the first centuries AD when there were major

refugee movements caused by the Gothic military campaigns up into the

Jutland Peninsula and southern Sweden. The Suebic grammatical forms

needed to converge with the indigenous Aestic grammatical forms, and so

an original

tervej kannuj (for example) evolved among these speakers

into

terv’e kann’u instead of reverting to the indigenous

tervet kannut

(which would sound unusual to people used to

tervej kannuj)

The following sentence below shows the general form used in regards to

an offering being made to

Rhea. It shows the most frequent

context in which the dynamic interpretation is desired.

(b)

mego dona.s.to vo.l.tiiomno.s. iiuva.n.t.s .a.riiun.s.

$a.i.nate.i. re.i.tiia.i. -

[bronze sheet MLV- 10 LLV- Es25]

Our brought-item ((ie offering), skyward-going, in the infinite

direction, into the airy-realm[?], to (=unite with) you of the Gods, to

(=unite with) Rhea

When you think about it, the idea of uniting with or joining with a

deity, or eternity, is more involving than merely moving to that

location or giving something to it – which is the reason in religion

today, it is more satisfying to ‘unite with God’ . In the case of the

Venetic context it is the spirit, rising to the clouds via the smoke of

burning, that unites with the deity.

2.1.5. “Iiative” Infix -ii- ‘extremely (fast or far or large)’

As we saw in the example above (b) one of the Partitive endings, the

one inside

re.i.tiia.i. is preceeded by -

ii- It is possible to

regard the -

ii- as a separate infix giving motion, or the entire

thing

iia.i. as an explicit expression of the dynamic Partitive. It

could represent a way by which the speaker emphasized the dynamism.

However, the double -

ii- appears elsewhere too and the example shows it

twice as well. Note the double “I” under the underlined parts:

mego dona.s.to vo.l.tiiomno.s. iiuva.n.t.s .a.riiun.s. $a.i.nate.i. re.i.tiia.i.

While there may have developed some degree of an explicit dynamic

Partitive in

-iiv.i. the appearance of the double

ii in non-Partitive

situations, made me decide that this was a more widely applicable infix

that added a sense of extremeness and or motion. See our discussions

about the infinite as well in the lexicon (ie the meaning of

.i.io.s.).

In the above

.a.riiun.s. the stem is probably

.a.riu- and three

elements are added:

-ii-,

-n and,

-.s. We note that the

-ii- occurs also in a similar way

vo.l.tiio which describes movement to

the heavens overhead, where we see no other ending. Here it seems that

the

-ii- is intended to exaggerate the size of the realm above. As

funny as it may seem, it could have the same psychological basis as

when an Estonian says ‘

hiiiiigla suur’ emphasizing the I’s in the

word meaning ‘gigaaaaaaantic’. Humans do this extension naturally, and

it is certainly possible that such inclinations could be formalized in

a language (ie systematically used, rather than purely on whim)

Note that in our determination that the dots were phonetic markers, we

determined that Venetic writing was highly phonetic – which means this

kind of doubling of the “I” could simply reflect the actual speech,

even if the sound in reality had no grammatical significance.

2.1.6. Inessive Case -v.s. ‘in; into’ (In dynamic meaning equivalent to Illative)

Static interpretation (‘in’): In today’s Finnic, the Inessive and

Illative cases are considered different, but as we decribed in 2.1.1

above, it seems originally, in the parent language of Finnish,

Estonian, ancient Suebic (from which the inscriptions Venetic came)

there was only the Inessive, interpreted in both a static and dynamic

way. And then in recent millenia, it became necessary to

explicitly distinguish between the two. But Venetic, remaining an

ancient langauge does not show this distinguishing, and for Venetic we

determine whether it is the static ‘in’ or dynamic ‘into’ from the

context. Was the action simply happening, or was the action being done

towards something else? Was something merely ‘being’, or ‘acting on

something’? An object that simply was, and did nothing onto anything

else, would take the static meaning. I already mentioned how in modern

English, we can use

in and the context could suggest it means

‘into’. For example “He went in the water” is technically incorrect,

but from the context the listener knows the intent is “He went

into the

water”. This shows how easily the correct idea is understood from

context, and why in early language it wasn’t necessary to have two

different case endings. Also, in early language, all speaking was done

in the context of things going on around the speakers and listerners.

If language became separated from being used in real contexts – such as

when it was used in storytelling or song even before written literature

– it became more important to explicitly indicate the required meaning.

There was another usage for the static form – as a namer. Many Estonian

names of objects end in

–s seeming to be a nominalizer. For example we

could begin with

vee ‘water’ form

veene ‘in the nature of water’ and

then add the –

s to get

veenes ‘an object associated with water’. This

could very well be the origin of vene ‘boat’ (same smaller boat

which acquired the name

rus as well in Scandianvia)

Venetic too appears to have such naming purposes for the static

Inessive. Because here, the –s creates a new word, the whole word is

now a stem, a nominative form. For example, the word

.i.io.s. (see full

sentence below) appears to be a word for ‘infinity’ formed from adding

the -

.s. and therefore we do not interpret it as ‘in the eternal’ but

simply ‘eternity’

If an additional Genitive is added, we arrive at a place name.

Modern maps of Estonia and Finland show a historic practice of creating

place names by adding either

-se which is like the Inessive and

Genitive, or

–ste which is like Elative plus Genitive, as for example

from

silla- ‘bridge’, giving town names

Sillase or

Sillaste. I like to

view these respectively as a name based on the sense ‘in the bridge’

versus ‘arising from the bridge’. In other words, the choice depended

on what suited the situation. We could take the

veenes example above,

and adding a Genitive sense with

veenese, it becomes a name of a place

‘(place) associated with the boat’

This can be found in some Venetic place names too. In Venetic, the

Adige River was called on Roman references

Atesis and the market

was called

Ateste. AT- meant

‘terminus’ and therefore we can interpret

Atesis as ‘(The river)

in the terminus (of the trade route)’, and

Ateste as ‘(The market that

)arises at the terminus’. Another Venetic town was

Tergeste, at

today’s Triest. This information comes from Roman texts, so we do not

know exactly how it was said in Venetic. How did the Roman form change

the ending?

Dynamic Interpretation (‘into’ = Illative) But if that object was

either entering or leaving that state, it would take the dynamic

meaning. We discussed the absence of an explicit Illative in Venetic in

2.1.1 This interpretation is common in the inscriptions,once

again perhaps because the abundant cemetary and sanctuary inscriptions

speak of the deceased or smoke travelling into the sky.

Note that the difference between ‘to’ in an Inessive situation, in the

sense of physical movement ‘into’, whereas ‘to’ in a Partitive

situation has a sense of uniting with, which is quite abstract. Thus

while English has the all-purpose ‘to’, in Venetic, that ‘to’ has

different meanings depending on the case ending. It makes the English

translation a little challenging. The Inessive case is underlined

in the following. Note I interpret it both with ‘in’ and ‘into’ as

required:

mego dona.s.to vo.l.tiiomno.s. iiuva.n.t.s .a.riiun.s. $a.i.nate.i. re.i.tiia.i

Our brought-item ((ie offering), skyward-going, in the infinite

direction, into the airy-realm[?], to (=unite with) you of the Gods, to

(=unite with) Rhea

The following is a good example showing the Inessive in a prominent

role, and in this case it is borderline whether the interpretation

should be ‘in’ or ‘into’ (hence I translate with in(to)):

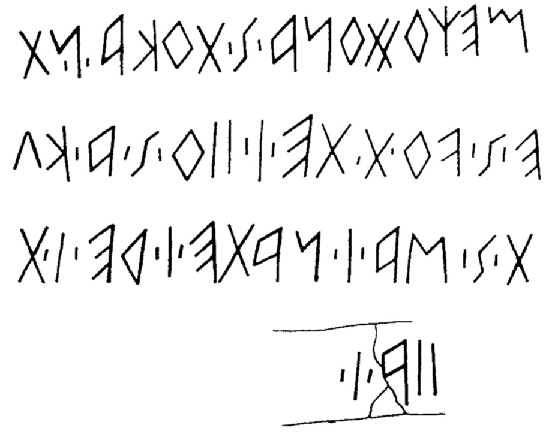

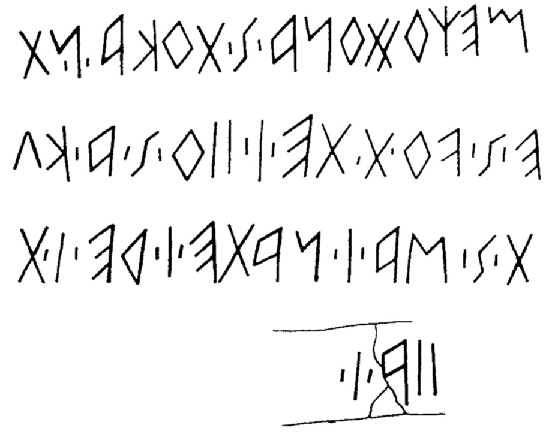

.o..s.t..s.katus.ia.i.io.s.dona.s.to.a.tra.e..s.te.r.mon.io.s.de.i.vo.s

[MLV- 125, LLV- Vi2; image after LLV]

expanded:.

o..s.t..s. katus.ia

.i.io.s. dona.s.to .a.tra.e..s.

te.r.mon.io.s. de.i.vo.s.

‘Hoping (alt. Out of being) the offering, would be disappeared, in(to) the eternity end, in(to) the sky-heaven terminus’

There seem to be two parallel word pairs (Finnic requires the same case

ending on connected words)

.i.io.s.

.a.tra.e..s. and te.r.mon.io.s.

de.i.vo.s. The two versions seem to be Venetic in the first pair

and loanwords from Indo-European in the second. This example shows how

the interpretation as ‘in’ or ‘into’ is not particularly crutial.

2.1.7. Elative Case - v.s.t ‘arising from; out of’

I include this next because we have already above discussed how –ste

can be used to name something. It is actually not so common in

the body of inscriptions.

Static Interpretation (‘arising from’) This is similar to the

Inessive, in that the static form seems to have most often served the

role of naming. Today Estonian and Finnish tend to view the Elative

case in a dynamic way – something is physically coming out of after

being in something. Thus as the table of case endings (Table 2 at the

end of these case ending discussions) shows, it is the static form that

is less known and less used today, which logically comes from the idea

of something being derived from or arising from something else. This

static form is the one that names things. As mentioned under the

Inessive, where the static form also names things, a town with a bridge

silla- could acquire a name two ways – with the static Inessive as a

description

Sillase, and with the static Elative with

Sillaste. Just as we referred to

Atesis for our example

with the Inessive, there was also the town,

Ateste at the end of

the amber route. In this case the meaning is ‘derived from, arising

from, the terminus (of the trade route)’. Another major Venetic city

was

Tergeste, which suggests ‘arising from the market (

terg)’

Interestingly the market at the top of the amber route, in historic

times called

Truso was probably in Roman times called

Turuse (or

Turgese or

Tergese) in that case using the static Inessive manner of

naming.) Of course, as mentioned under the Inessive, it was not just

used for place names, but to derive a name for something related to

something else. I gave the example earlier of

vee >

veene > veenes which could refer to a boat and eventually reduce to

vene. We could also have veenest but it would name something

arising from water (like maybe a fishing net?) The difference between

naming with –

s(e) and naming with –

st(e) is whether the item named is

integrated with the stem item, or arising out of the stem item and

separate from it.

In the Venetic sentences, there are nouns that were originally

developed from this static Elative ending. For example

.e.g.e.s.t- is one.

.e.g.e.s.t- could be interpreted as

‘something arising from the continuing’ = ‘forever’. The common

dona.s.to could be interpreted as ‘something arising from bringing (

do-

or Est./Finn

too/tuo)’ Another is

la.g.s.to which I interpreted

as ‘gift’ but internally means ‘something arising from kindness’. (The

reader should review my interpretations of the –ST words in the lexicon

from this perspective – the stem word plus the concept of ‘arising

from’.)

Dynamic Interpretation (‘out of’) This is the common modern

usage in Estonian and Finnish and this is the meaning we will find in

their grammar describing case endings. The dynamic interpretation of

the Elative in the body of Venetic inscriptions depends on our

determining there is movement involved. The static meaning ‘arising

from’ is abstract and there is no movementm but the dynamic meaning

‘(moving) out of’ involves movement. Perhaps the

.o.s.t..s. in

the recent example sentence in the last section is one, as movement

occurs in that sentence.

In general the Elative is less common in the known inscriptions because

the concept of something travelling ‘out of’ or even ‘arsising from’

something else was not particularly applicable to offerings towards the

heavens or the Goddess whenin things are going ‘into’ not ‘out

of’.

Most often, whenever the -.s.t appears in Venetic, it appears to be the

static kind where there is no movement, and it produces a new noun stem

from the more basic stem.

2.1.8. Genitive Case –n OR [naked stem] ‘of, possessed by’

Static Interpretation (‘of’) vs Dynamic Interpretation (‘coming into possession of’)

Estonian today lacks the

–n Genitive which is standard in Finnish.

Estonian simply uses the naked stem. For that reason (considering also

the tree chart of Fig 2.1.3) we must investigate the inscriptions to

determine if Venetic had an

–n Geneitive, a naked stem, or both.

What I found in the Venetic sentences was that the idea of possession

seems often to be expressed by what seems to be the compound word

form. In a compound word, the first part is the stem and takes no

endings, while the second part takes the endings. But given that in

modern Estonian the Genitive is purely the naked stem, these first

parts of compound words are indistinguishable from Genitives. For

example Venetic

kluta-viko-.s. is a compound word, the first part

interpreted from context as ‘clutch’ (of flowers) and the second as

‘the bringing’. But the first element,

kluta, could very well be seen

to be in the Genitive. It may be exactly such overuse of compounding,

that developed the use of the naked stem as Genitive in Estonian, with

the consequential abandoning of the

–n at the end, while it endured in

Finnish which derives from the earlier ancestor language.

Nonetheless, the

–n does appear a number of times in a way that makes

it seem to be joining concepts. For example in

iiuvant

v.i.ve.s.tin iio.i. -

[MLV -138, LLV-Pa8

] we see the

–n appearing in a way that makes it seem

Genitive (

v.i.ve.s.tin iio.i. seems like ‘the conveyance’s infinity’).

The same occurs in

pilpote.i. k up. rikon .io.i. -

[MLV-139, LLV-Pa9;]

in which

rikon .io.i. seems like ‘nation’s infinity’.

We also see the

–n appearing in the example

mego dona.s.to

vo.l.tiiomno.s. iiuva.n.t.s .a.riiun.s. $a.i.nate.i. re.i.tiia.i. Other

examples include

kara.n.mnio.i and voltiio.n.mnio.i.

To summarize it seems more common to find in Venetic the bare stem in a

situation that looked like a compound word. It is possible that while

the n-Genitive was still in use in the inscriptions; however, the use

of the bare stem in a fashion almost like a Genitive was also in use.

The disappeance of the n-Genitive in Estonian may have occured in this

way, that is to say, from the latter becoming more and more

common. My conclusion is that Venetic had the –n Genetive, but

lazy speakers dropped it. (Linguistic change often arises from lazy

speech where endings are dropped.)

2.1.9. Essive -na ‘as, in the form of’; ‘becoming as.’

This ending is almost as common in the body of inscriptions as the

Partitive and Inessive. We will assume for the sake of argument that

this case ending too had both a static interpretation and a dynamic

one, depending on context. I propose this was the case for all the

Venetic case endings; but some case endings were more dramatic in the

difference between the static interpretation versus dynamic - for

example case endings about location. Here were are speaking of form,

appearance and the differentiation between static and dynamic meanings

is not significant in this case as it is a more abstract concept, and

abstract concepts are quite static by nature compared to concepts

involving actual physical movement or lack of movement.

Static Essive: In the static interpretation this ending has the meaning

‘as, in the form of, in the guise of’ For example it appears in

$a.i.nate.i. where

$a.i.na is seen as ‘in the form of the gods’

It appears more commonly in the inscriptions with an additional

Partitive attached, giving

-na.i This added Partitive usually

results in a very dynamic meaning, which appears to be like Estonian

Terminative ‘till....’

Dynamic Essive: I do not know if there is a clear example of this in

our body of inscriptions, except for the situation in which an

additional .i. is attached as mentioned above – as in -

na.i. The

dynamic interpretation would mean ‘assuming the form of’ It would

need to have a verb behind it, such as ‘he changed into....’ It

is purely a question of whether there is a motion towards. In any

event, I believe the speaker or listener understood what was intended

from the context

2.1.10. Terminative -na.i. -ne.i. ‘up to, until, as far as’

This ending appears often. It looks like a Partitive ending added to an

Essive ending and originally my interpretations tried to combine

the Essive meaning with Partitive and got confusing complex results

like ‘in the form of joining with’ and then one day I hit on the

simpler idea of the Terminative – ‘up to, until, as far as’ – which

exists in Estonian but not Finnish. Already we have evidence that

Estonian and Venetic/Suebic were related through a common parental

language, and so something found in Estonian could be represented in

Venetic, even if not represented in Finnish.(We have already seen for

example, that we cannot tranform a Finnish Partitive to Venetic, while

we can transform an Estonian Partitive to Venetic by changing the

–T,D ending to –J (.i.))

Without much rational justification I applied the Terminative meaning

everywhere it occurred and it fit better than my complicated combining

of Essive and Partitive concepts.

This case ending might also have static and dynamic interpretations. If

so, I would say that the

static interpretation is as in

pupone.i.

– something (the duck

rako) is physically

given to, in the

example

pupone.i .e.go rako.i.

e.kupetaris To(‘til) the elder remain a duck, Bon Voyage. This

static intepretation seems very much like a Dative.

Meanwhile the

dynamic interpretation would be to

physically travel

until somewhere which is how Estonian uses the Terminative. The

Estonian Terminative can be seen in

Ta läks taluni ‘he went as far as

the farm’

In Venetic, for example in a funerary urn inscription

v.i.ugia.i.

mu.s.ki a.l.na.i. ‘

to convey my dear (?) until down below’

the word

a.l.na.i. appears to be in a context with physical

movement. (Hmm. Perhaps the static form is

–ne.i. and the dynamic form

is

na.i. ?? There remains a question as to the signifance of using

e

instead of

a. )

2.1.11. Adessive -l ‘at (location of)’& Allative -le.i. ‘towards (location of)’

The Adessive in the meaning ‘at (location of)’ represents the

static interpretation. In this case it seems Venetic

does have an

explicit dynamic form which parallels what is in relation to Estonian

and Finnish called the Allative ‘towards (location of)’.

One may ask, why does Venetic have the explicit Allative, when it did

not have the explicit Illative? To understand what Venetic is

expected to have and what not, we can look at what is common in

Estonian and Finnish. If a case ending exists in both Estonian and

Finnish in a similar way then it is very old, and

must exist in

Venetic. Our tree chart of Fig 2.1.3 showed the descent of Inessive,

Partitive and Illative. If we were to add Adessive and Allative, we

would show both existing at the common ancestor of all three languages

– Estonian, Venetic/Suebic, and Finnish. These two separate forms could

have developed in an early stage of Finnic perhaps because in the lives

of early hunters of northern Europe, it was important to distinguish

with being at a location versus going towards a location. Too important

to clarify via context.

In Estonian Adessive is reperesented by

-l, Finnish by –

lla which is

essentially the same (Est. has lost terminal a’s on case endings). And

the Allative, which is equivalent to a dynamic interpretation of the

Adessive, is found both in Estonian and Finnish as –

le and –

lle

respectively.

Unfortunately in the body of inscriptions available to study, the

Venetic Adessive and Allative occur only a couple of times, so we do

not have many examples. The most significant sentence is the following.

It is written on one of the Padova round stones left at the bottom of

tombs, and on which most of them are telling the deceased spirit to fly

up out of the tomb. The first underlined ending I think is the Allative

and the second is Adessive.

(a)

tivale.i. be.l. lene.i. -

[round stones- LLV Pa 26]

‘towards wing, on(at) top of, to fly! (Est.

tiivale peal lendama!)(=tiiva peale lendama!)

I propose that the ending

-le.i. on

tivale.i. is an Allative (‘to

location of’) while the

-.l. on

be.l. is the Adessive (‘at’).

Note that the stem of

tivale.i. is

tiva, and its meaning is

confirmed by the handle-with-hook that has

kalo-tiba on it (=Est.

‘

kallu tiib’ ‘wing for pouring’ ) The latter is in the Lagole dialect.

Here is another example with tiva in the inscription and here it

appears with the Adessive ending (-l) to which is added an iio.i. which

seems to mean ‘to infinity’)

(b)

vhug-iio.i. tival-iio.i. a.n.tet-iio.i.

eku .e.kupetari.s .e.go -

[figure 8

design with text - image of Pa26]

‘

Carry infinitely, upon wing to infinity, the givings to infinity, so-be-it happy journey, let it remain’

We can interpret

tivaliio.i. as

tiva + l + iio.i.

2.1.12. Ablative -.l.t ‘out of (location of)’

The Ablative also exists in both Estonian and Finnish in a

similar way and therefore must exist in Venetic from its origins in the

northern Suebic.

The Ablative (-

.l.t) to Adessive (-

l)and Allative (-

le.i.), is similar

to the Elative (-.

s.t) in relation to the Inessive/Illative (-.

s.). The

difference is that one deals with physical location, while the other

(-.

s.t) deals with interiors.

Static Interpretation of the Ablative (‘derived from location

of”) Similarly to the Elative (

.s.t) the Ablative

(-

.l.t) probably was mostly used to create nouns, to name things, but

in this case related to a location - on top of it, not inside it.

An example in Venetic is the word

vo.l.tiio Could it have

originated with AVA ‘open space’? AVALT would then mean ‘derived from

the location of the open space’ This seems to accord with the

apparent meaning of

vo.l.tiio as ‘sky, heavens’. But like -

.s.t in

dona.s.to, it is not a free case ending, but now incorporated in the

word.

Dynamic Interpretation of the Ablative (‘from the location of’) This is

the common usage in modern Estonian and Finnish – to physically move

away from a location.

Ta läks talult eemale ‘he went away from

the farm’ Do any of the inscriptions indicate movement from one