Before the Roman era, there

were peoples and languages in the Italic Peninsula who were

inspired by a new development - writing. Phonetic writing probably

developed among long distant trader peoples, who needed writing that

actually reproduced the sound of a language so that they could create

phrasebooks in the languages of their customers. This practice is

especially well-known for the Phoenicians. A by-product of the

development of phonetic writing is that it could be put on everyday

objects to in effect make them speak. Originally it would have been as

fascinating as in recent history recorded voices being added to toys.

The long distance traders from the north, who ancient Greeks saw as

'barbarians' (literally meaning people who spoke an unintelligible

language), were probably speakers of a Finnic language, since long

distance trade was by coasts and rivers, and the northern boat-using

hunter-gatherers were preadapted to take on the role in a Europe

consisting of settled people in interiors who would not even have known

how to build proper boats. This truth suggests that major

southern terminals of north-south trade - especially amber trade for

which the Veneti were known - spoke a Finnic-like language, even if the

larger world around their southern terminus colonies spoke an

Indo-European language like Greek, Illyrian-Slavic, or early Latin.

This common sense notion motivated me to try to interpret some short

inscriptions on common everyday goods found in the Italic Peninsula

from before the expansion of Rome. Having been raised from a child in

the Estonian language, I tried to listen to the writing with the

intuition of someone with Estonian as a child, to see if I could detect

a sentence that was supported by the object. The linguistic

principle for doing so it the fact that there exists in every modern

language, a core common language that is passed from generation to

generation to children, without change. The most common language tends

to have a greater inertia than specialized language where the words are

not used often and easily displaced and changed.

The ancient Etruscans were fond of creating highly marketable objects

for the general consumer - hand mirrors, ale tankards, etc. Not all

have the novelty of writing, but the ones that do can reveal some

surprises. Of particular interest are hand-mirrors with writing

on the back. Archeology has found some with elaborate

illustrations of scenes from mythology. The names of the deities are

clearly identifiable. However, the problem with trying to interpret

those, is that it is necessary to know the mythological situation

depicted in order to confirm any hypothesis about the language. I

needed to find a sentence where the sentence was related to the nature

or use of a hand-mirror. How suitable would the translation be for the

object, for a hand-mirror. How appropriate would the sentence be, and

an appealing feature at a marketplace?

ETRUSCAN HAND-MIRROR

I discovered generally that the

Etruscan language was too diverged from even simple Estonian for any

result to be convincing. However there was one inscription on the back

of a mirror that employed a few of the most common words in Estonian

such as

näe! 'see!'. That word could very well be many thousands of years old and widely used in pre-Indo-European trader Europe.

The Etruscan sentence on the back of the elegant hand-mirror, converted to Roman alphabet reads:

MIZKITNASVEHNASVEHSNAROA

Making a connection between viewing yourself in a mirror and seeing oneself, I immediately saw the Estonian

näe! look, stem

näge- 'look, see, show' and also

naer 'laugh, smile' and divided up the continuous text as follows

MIZKIT NASVEH NASVEHS NAROA

This resonates to the Estonian intuition as an extreme dialect saying

what in today's Estonian, with some valid dialectic liberties. For

example

miskit is a valid alternative to

mida, and

näeva is a present participle whereas today we would use the infinitive

näha 'to see'

Miskit näeva? Näevas naeru

The closest literal translation into English: "Whatsit to be seeing? (In process of) seeing a smile"

Which is totally appropriate for a hand mirror! In modern Estonian idiom one would express the idea more like

Mida näed? Näed naeru. 'what do you see? You see a smile' or

Mida näha?

Näha naeru. 'what is to see? To see a smile'

But as I say, Etruscan is very old, going back 3000 years or more, and

it would have deviated considerable from any language common also to

the roots of Estonian. I did not pursue Etruscan objects more, even if

I could give a couple examples of inscriptions on tankards-. Other

inscriptions would not be as obvlously suitable for the object like the

above- All we have to support our hypothesis is the nature of the

object.

The ancient Veneti of northern Italy developed at the south end of the

amber trade route that came south from the Elbe, and descended the

Adige. The amber trade made intimate connections between the Baltic

sources of amber and the Mediterranean. Greece was one of the major

destinations. Since the amber sources were at the Baltic, and the

largest source of amber was at the southeast Baltic, it seemed that we

might find an even greater resonance between common Estonian and the

Venetic objects. Although the number of Venetic inscriptions dating

mostly to the centuries before the rise of Rome, is not great (less

than 100 complete sentences and less than 300 fragments) almost all the

inscriptions were very short sentences on object whose character and

purpose are understood and would serve both as a guide and proof for

the interpretations. Most of the Venetic objects are those found at

ancient sanctuaries or cemetaries, so the bulk of the writing are on

cremation urns, tomb markers, and items dedicated to the goddess Rhea;

so actual consumer oriented items we can dissect are not great. The

following are a few very convincing examples.

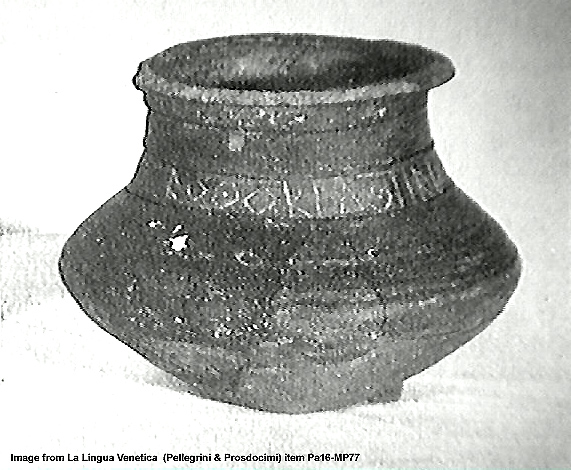

AN ELEGANT VASE

The image above, shows a very elegantly designed vase. Unlike another

vase and other objects that appear to be custom inscribed with a prayer

to a diety, etc. and the inscription is obviously added after the

object was made, this vase, like other objects that appear to have been

made repeatedly for the marketplace, incorporates the text into the

design. As we see in the image, the text goes around the neck of the

vase within a band. The image is not in colour, but we can

imagine it was attractively covered.

klutiiari.s.

Archeologists have determined this was a vase, and so I set out to see

if the text was as suitably designed as the rest of the vase. We are

looking for a universal sentence, and not the typical prayer or

memorial normally inscribed on the common funerary or memorial objects.

The Padova area, where the vase was found was a major market city in

Venetic times.

The sentence going around the neck, when converted from the Venetic alphabet to the Roman alphabet was

votoklutiiari.s.vha.g.s.to

Ancient texts were intended to purely mimic actual speech, and so the

reader had to know the language enough to place the emphasis and

intonations in the right places. Venetic writing added dots as

additional phonetic markers where the sound departed from the normal

pure sound, such as palatalization. But ultimately the solution was to

add spaces or dots to identify words. It was begun by Etruscans and

copied in Latin. Here, because today we have rationalized

languages in terms of a sequence of words with grammatical endings, it

is useful in the analysis to break up the Venetic continuous writing

into words. This of course has to be done correctly of course, as there

are potentially many ways to divide a continuous row of letters.

In this case we could see that

voto was a separate word from its appearance in other inscriptions. That left

klutiiari.s.vha.g.s.to Another

indication of a word boundary is grammatical endings seen repeatedly in

the inscriptions. In this case there is the first

.s. We can then reliably divide the sentence as follows:

voto klutiiari.s. vha.g.s.to

The is in other inscriptions some evidence that voto is connected to

'water' the liquid. Without an ending, it follows the pattern of the

imperative form. Next, the third word

vha.g.s.to sounds remarkably like Estonian

väga 'very' and even more closely

vägevasti

'strongly, energetically' Since these words are very common,

probably used a dozen times a day, they probably have the required

inertia to have survived with little change since the time of the

Venetic inscriptions. (Our linguistic methodology is to ensure

decisions are made from words in daily use, which will have been passed

down generation after generation.)

So if

vha.g.s.to is interpreted with

vägevasti then with

voto

being 'water' the word seems to refer to the contents

of the wase as in 'water [the contents of the vase] strongly'. This

would not be a common word, and therefore would not have the same

inertia. Nonetheless Estonian has the word

klutt to describe a tuft of hair or something. Furthermore there is in Estonian

hari, meaning 'arrange, brush' so that

klutiiari.s. sounds

like it means 'arranged bunch' or 'cultivated bunch'. In English

there is the word 'clutch (of flowers)'. Regardless of the actual

origins and evolution of the word, it becomes clear from

voto ----

vha.g.s.to that

klutiiari.s.

describes the flower arrangement in the vase. It makes complete sense

that a very universal message on a vase would be 'water the flower

arrangement well'.

This result is exactly what you would expect on a marketed object where

the text is incorporated into the design and therefore it would not be

surprising if archeology might find more of the same design. A good

design is repeated over and over.

A SET OF ALE TANKARDS AT A TAVERN ALONG THE PIAVE VALLEY ROUTE

Another example, where the object apparently was found in identical

form three times, comes from the Piave River valley, which was the

major trade route from the north, after Rome became a major destination

for merchants. There were two major routes that came down to the

north end of the Adriatic - one came down the Adige, and the other one

came down the other routes from the Baltic, originating from the

southeast Baltic. Merchants/traders coming down from the

southeast Baltic would have spoken the dialect there that would have

been closer to today's Estonian. This analysis has no effect on the

analysis, but explains why the following inscription was easier to

interpret via Estonian and Finnish language intuition. The merchants

the writing was for may actually have been speaking ancient Estonian as

it was in the first century of the Roman Age. These inscriptions,

written on ale tankards, may have been deliberately inscribed to be

readable by these merchants from the north, stopping at a tavern along

the route, who were not familiar with Latin. This is a believable

deduction because in this case the text is actually written in the

Roman alphabet, even though the language is Venetic, or at least an

Estonian dialect of Venetic. (The traders were actually called

Venedi a word that originates from

Venede 'people of the boats')

This is one of the very few inscriptions written in the Roman alphabet

during the Romanization period, that is in a proper Venetic

language. After the Romanization there were still outlying

areas where Venetic was the primary language.

The Roman alphabet form eliminated the Venetic phonetic dots markers,

and shows word boundaries with dots. The fact that Venetic could be

written in the Roman fashion proves that the Venetic dots are not

necessary when word boundaries are used. We can understand this if we

write this text

withoutanyspaces.

The Venetic alphabet approach would be analogous to adding marks to

suiggest how the actual speech is broken up as in using an apostrophe

as in

with'out'a'ny'spa'ces for

example. (Venetic dots were more sophisticated, in putting dots around

letters that were in one way of another palatalized, including "sh"

repesented by

.s. or a trilled r with

.r. But

here we need not be concerned about the character of Venetic

writing, because here we have a very long sentence written in a proper

Roman fashion.

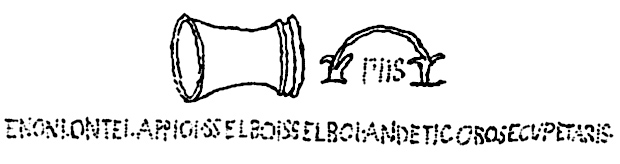

This incription, is shown in the illustration above, as drawn by its

finder, showing on paper the object, its handle, and the manner in

which the text was written onto the object.

The inscription reads (dividing the sentence at the dots)

ENONI ONTEI APPIOI SSELBOISSELBOI ANDETIC OBOSECUPETARIS

It was engraved on a container found at Canevoi di Cadola, a

village on the Upper Piave River . The object has been lost, but

the drawing and information was preserved by canon Lucio Doglioni

from Belluno, the author of several studies of Belluno inscriptions.

Etruscanologist Elia Lattes was first to publish the drawing of the

bucket and the inscription.

This container was 30 cm long with a 15 cm handle, made of

lead, concave sides, with a handle. The finder wrote that

he had seen two other identical ones – which suggests it was part of

quite a number of identical ones, which is why I propose it was part of

a set of ale tankards in a tavern.

Besides the believability of a set of tankards at a tavern along the

Piave valley trade route, there are other indications it was an ale

tankard. The size 30cm long, and it looks like maybe 15cm across, is

too small for a bucket. Furthermore, there is no indication of any

bucket-type handle being connected from the top. The illustration

shows the separated handle with points on the end. This suggests that

the container portion had two holes drilled into it, and the points

were pushed into holes on the sides. The size of the handle -

15cm - is about right for a man's hand.

But the real evidence that this was an ale tankard among a set of such

tankards used at a tavern will come from translating the sentence.

The regular academic interpretation of this inscription by the

traditional scholarly studies of Venetic as an archaic Indo-European

language, could only get a translation by making most of the words into

proper names – a trick common to traditional analysis. For example a

translation given by Micheal Lejeune in

Manuel de la Langue Venetique

was ‘Burial vault of Ennonios for (his brothers) Onts (and)

Applios (and for) himself, (all three) sons of Andetios’. Although not

absurd, it is completely empty and not only makes parts into

meaningless proper names, but assumes ideas in the brackets.. This act

of regarding pieces as meaningless proper names is unacceptable since

we know ancient names had meanings themselves (as we still see in

modern names surviving from ancient origins). Another interpretation of

the Canevoi bucket using Slovenian was done by Matej Bor, completely

ignoring the word boundaries, and is equally absurd ‘And now, drunken

as you are, have fear, have fear even of children around you, when you

travel.’ And of course, it was necessary to add a paragraph of

explanation of children being malicious to drunks, etc. While anything

is possible, it would be highly unlikely to appear on such an object.

There were three trader routes identified from dropped/lost amber -

south via the Elbe and by various rivers to the Innsbruck area and

south on the Adige River, .down the Dneiper to the Black Sea area, and

south on the Vistula transferring to the upper Oder and reaching the

Vienna area and then south to the Adriatic from the east side.

The region of the Veneti were at the southern terminus of the two

routes that came down to the Adriatic. The route from the

southeast Baltic beginning at the Vistula originally was keen to reach

the great market for amber at ancient Greece; but with the rise of the

Romans, some of the traders turned further west, and came down the

Piave, in order to reach Roman markets. (The name Piave, in Latin

Piavis, sounds remarkably like Finnic

pea vee, or

pea viise,

'main waterway' or 'main river-route') They are very common words

and therefore would have been perpetuated through the last couple

thousand years.

Scholars have never considered Finnic language, since the academic

world has never considered that the Baltic peoples who handled amber,

and were expert in boat travel, spawned professional traders and

exploitation of southern interest in northern products like amber,

furs, honey, and other exotic northern products. Having already

found some evidence of an Estonian-like language in the Venetic

inscriptions, I tackled this sentence with my Estonian intuition (this

is something one gains as a child from direct learning without the

intellectual rationalization of adult language learning.)

The most valuable aspect of this inscription is that the word

boundaries are defined, because traditionally analysts trying to find

something Latin-like or Slavic-like in the inscriptions, simply tried

to hear some words, and then divided the continuous text to suit what

they thought they heard. It would be analogous to listening to a clock

ticking and translate the sound into 'tick-tock'. The explicit

identification of words makes it impossible for a false interpretation

being created from convenient custom division to suit what the analyst

thinks they hear.

We first note the word ECUPETARIS we see often tagged at the end of

some sentences and which suggests a ‘happy journey’ concept. In

front of this word is OBOS, giving OBOSECUPETARIS. If OBOS means

'horse' as suggested by Estonian

hobus

(a word that has Indo-European origins since horses were not originally

found in the north), then we see a compound word meaning 'happy

horse-journey' In the memorials with pictures of horses there was

an inscription in Venetic alphabet

v.i.ug-iio.i. .u. posed-iio.i. .e.petari.s. in which

.u. posed appears to mean ‘horses’. The singular would then be .

u.pos, which

looks much like the OBOS here. Such additional cross-references are important to help confirm choices.

We then notice ANDETIK We note that the word ANDET appears in other

inscriptions and a very believable meaning everywhere is ‘successes’.

Modern Estonian has the word

andekas

'lucky, talented, successful'. This too is a commonly used word that

has enough inertia to have lasted since the time of the Veneti.

This enables us to view the end portion ANDETIC OBOS ECUPETARIS end portion as ‘have a successful horse-journey'.

Working backwards through the sentence we next see SSELBOISSELBOI which

is clear reduplication of SSELBOI. Such repetition suggests a

repeated action, or emphasis. If we are talking about a successful

horse journey then we want to find a word that can be associated with

horse-riding.

It is here that the Estonian ear helps. Estonian uses reduplication in

Selga, selga ‘onto the back, onto the back’ as applied to a horse.. As already discussed earlier, the presence in Venetic of the suffix

-bo- ‘side’ suggests BOI is a suffix or case ending that is based on

-bo- and partitive (vowel)-I giving the meaning ‘to the side of’. The Estonian

selg ‘back’ appears to be an ancient word as it exists in Finnish as

selkä. Thus we can propose that SSELBOI is formed from SSEL- stem meaning ‘back’ and -BOI which is not exactly the same as Estonian

selga, selga but produces the same meaning. For those knowing Estonian it would be analogous to

selj-poole.

In this sentence the partitive ending (v)I occurs several times. It’s

meaning is typical of the complex application of partitives in Finnic,

and appears to have the meaning ‘to, towards’ as there is a sense of

action in a direction.

Estonian has the word

appi

as an Illative type of word meaning ‘to the aid’ which suits the

previous word APPIOI except other evidence suggests it is actually in

the infinitive 'to aid' rather than 'to the aid'.

ONTEI sounds like Estonian

on teid ‘is your’ The ending is here to be interpreted in the Partitive.

Thus we have so far the equivalent of the Estonian

on teie appi ‘is to aid’

What is ‘(in)to your aid’? Since it is a container, and may involve a

horse, how about water from the container to quench the horse’s thirst?

But this is not believable. The object, as already mentioned, is

probably an ale tankard. Thus we have to find in the word ENONI,

something connected to thirst and whatever is in the container.

With an Estonian ear, we immediately hear

jänu 'thirst'. Finnish has preserved

-ni ending as a possessive pronoun meaning 'my'; hence ENONI sounds like it means 'my thirst'

If these interpretations are incorrect, then when we put it all

together, the result would sound absurd. But if correct, a sensible

sentence will appear. The result using added information from Estonian

would be in Estonian

jänuni (my thirst)

on teie appi (=

teie abitsenud mind). (have you aided)

Selga, selga. (selja-poole, seljapoole) (onto the back, onto the back)

andelikkut hobus-reisi (have a successful horse-journey)

‘My thirst you have aided. Ontotheback, ontotheback. Successful horse-journey-continuing!’

The most believable way of interpreting this, is that the drinker is

thinking this, and directing it to the tankard of ale, now empty. You,

ale, have helped me by quenching my thirst. Now it is time to continue

on, to get on the back of the horse outside, and to continue on to a

successful horse-journey. In addition to the sentence being believable

(and can be shown to have grammatical closeness to Estonian grammar)

the resulting sentence is perfectly suitable for an ale tankard in a

tavern. The sentence expresses what the drinker thinks after

having downed the ale.

In addition there was the word on the handle of the bucket, where the

first letter looks like it was a P, giving PIIS. It can be interpreted

as ‘handle’ from

pidese >piise >piis.

What else could a single word on the handle mean, other than

‘handle’? The handle with its pointed ends, I believe was

attached by pushing it into holes in the side of the container.

This inscription also illustrates how important it is in our

methodology to always select not just the interpretation that is

possible, but the one that is most realistic, the one that most follows

grammatical structure, and results in the most believable result.

For example, it is possible to come up with other interpretations

such as the absurd ones via Slovenian or Latin which the analysts can

argue are ‘possible’. But it is the interpretation that ‘works’

on all levels that is by the laws of probability and statistics, most

probably correct. Strange interpretations always reveal themselves to

have flaws on all levels.. For example interpreting SSELBOISSELBOI with

Estonian

sel poisil sel poisil ‘of that boy, of that boy’ instead of s

elga, selga ‘onto the back, onto the back’ can produce a worse, even absurd, sentence.. We can tell that

sel poisil is a worse interpretation than

selga for a number of reasons.

Sel poisil breaks the SSELBOI word against suggested word boundaries, and it adds an additional

-il at

the end.. Thus in the direct approach the interpreter must be trying

their best and always seeking the best fit and realistic results -

closest to word boundaries, grammar, etc.. This applies to

employing other languages too. We can take modern English for example.

What can we get if we identify in the above inscription some vague

English sentence? “Anon – on the – apply – sell boy sell boy – and

ethic – oh boys – occupy taris”. If the analyst were fanatic like some

analysts can be, he could probably poetically massage this result to

get a meaning that, still absurd, formed a ‘poetic’ sentence, and then

accompanied it with a long explanation. Furthermore, it will be

impossible to find the same meaning of the same Venetic words in other

inscritpions, nor the same grammatical operation.

In a sentence – while it is possible for anyone to find a similar

sounding sentence in any language, it will be like hearing sentences in

the wind. A proper analysis of Venetic requires the full analysis of

all the inscriptions at once, with constant cross-checking of any

hypothesis. There is no shortcut. It is impossible to interpret Venetic

in a piecemeal fashion. The entire body of known inscriptions must be

analyzed at once and the results highly realistic and clear.

But our purpose here is to highlight examples of objects that appear to

have been crafted over and over in order to serve a marketplace so

that the writing on them will have a common universal saying

appropriate to the object and appearling to the customer who buys

it. These objects demonstrate that what we see today in

manufacture and marketing, already existed two thousand years ago in

the Italic Peninsula, in a languae other than the more common Latin or

Greek.

How about an object used in ancient times to freshen the air inside a house?

A TINY CONTAINER WITH A ROUND BOTTOM

Among the Venetic objects with inscriptions, there are two inscribed with the same words.

lah.vnahvrot.a.h

In this case they are not identical objects, and therefore were made by

different craftsmen; however, these are objects that would have been

crafted many times and intended to be sold at markets. Both of them are

small containers and one can speculate what they were used for?The

following illustration shows the more elegant-looking one. Let us

interpret these objects from their appearance. What could they have

been used for?

The one illustrated here has a handle that shows holes for thumb

and forfinger. The bottom of the little pot is round, meaning it was

not set down anywhere. It was carried around and then put away. What

does this context suggest? The first thing that comes to

mind is a portable oil lamp analogous to later candle holders – to

carry around to find one’s way in the dark. But examples of such oil

lamps in other cultures suggests it should have a flat bottom to set it

down.

Another practice involving carrying something around would be to

perfume an environment. A flat bottom is not necessary if, once the

rooms are perfumed, the task is complete, and doesn’t need to be

continued.

We all the while bear in mind the fact that the same words appear on

another small pot, which tends to suggest the object was designed for

general customers and the words were not custom-made and were most

probably a label for the object or what was inside.

Thus from studying the context we can come up with some ideas of

probable use, and from that propose some meanings. Our first next step

would be to look through all other inscriptions to see if similar words

appear. In this case we cannot find the words anywhere else other than

the second pot.

All we have determined so far is that the object was crafted, and the

words describe the object (‘small pot?’) or what was inside (‘lamp oil’

or ‘perfume’)

We have, thus, a general expectation. We can continue to search

evidence for more clues. As we discussed earlier, we can extend our

accumulation of clues to external languages. But it is wise to do so

only when we have already determined a rough meaning from direct

interpretation. We have done so. We expect the meaning to be likely

something connected with perfuming a home.

With that in mind, when we now look at external languages (Latin,

Etruscan, Germanic, etc) we find that in Estonian we can mimic the

Venetic with

lõhnav roht ‘aromatic herbs’.

What is the probability of such closeness occurring by random chance onto two similar objects!?

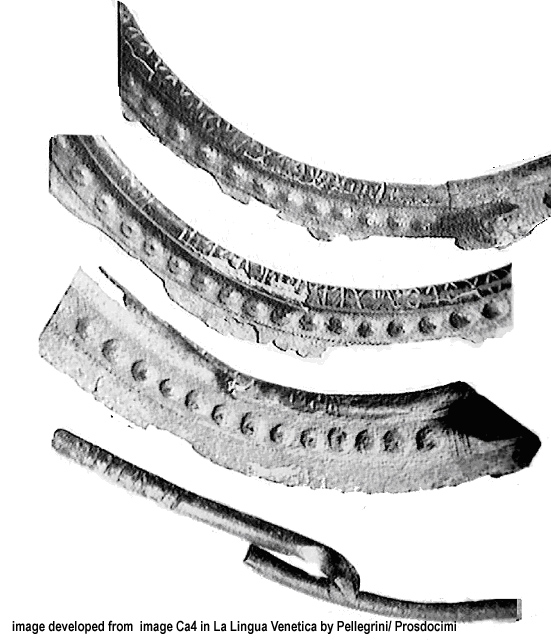

AN ADVERTISEMENT ON A CONTAINER?

As our final example, we will not describe an object that would have

been manufactured over and over, since we have no idea if was. But this

is worth looking at because it has, in tiny letters on the rim of a

container, some text that appears to be blatant sales promotion.

The container is in pieces, but what is interesting here is the tiny

text incribed on the rim. What could be the purpose of this tiny

writing. Today if we see tiny text on a product, it will describe

things like manufacturer, country of manufacture, etc. But at this

early date industry and commerce were not so organized. We are speaking

of centuries before the Roman Empire. There are many possibilities,

form the crafter trying to be poetic, to recording some kind of news

connected with the object. It would seem to any archeologist that

the object itself would provide no guidance in what is written in the

tiny text.

However this is not entirely true. The object was found in the

Piave River valley, which means it was found along the ancient trade

route from the north. (like the tankard discussed earlier). The

container, which seems to have been of elegant design, was not a

utilitarian pail. This information does not narrow down the

possibilities much, but it may be enought to tell us if our

interpretation of the inscription can believably be explained in

this context.

The text, converted from the Venetic alphabet into small case Roman, reads as follows:

.e..i.k.go.l.tano.s.dotolo.u.dera.i.kane.i

The inscription too does not provide much if anything that is repeated

in other inscriptions. But in this case, if spoken out loud, it sounds

like it is in a dialect of Estonian. To read it properly letters with

dots around them represent palatalization - which is like adding a

short "I" in front of a consonant. or a "J" (pronounced like

English "Y") or an "H" produced at the front of the mouth. This

means the first letters

.e..i.k. sounds much like a very common Estonian word

ehk, generally meaning 'in case that'.

There are grammatical endings in the text, that help us find word boundaries. At the end we see the endings -.

a.i.

which appear to be in the partitive. An .s. might indicate an

inessive case, but this assumption doesnot work. We have to

simply take the plunge and produce an interpretation and then text it

for grammar and meaning.

Long story short, I found a perfect parallel with Estonian

ehk gulda, ni ostad õlu, terve kannu

The meaning is 'In case (you have) gold, then you buy ale, a whole

container'. There is absolutely no rational reason it is correct

other than the circumstances of being along the trade route coming down

the Piave and originating in the Baltic, but the Estonian version

parallels the Venetic grammatically.

If we accept it is correct, then why is it written in tiny letters on a

rim? The answer is simple, if it is an ale container, the drinkers will

get very close to the rim and read it. In such a context, it could have

been in a tavern serving containers of ale to travellers seated at

tables. The tiny letters would then be an advertisement encouraging the

purchasing of whole containers of ale.

Either it is an extraordinary coincidence, or it is correct.

F u

r t h e r S t u d i e s

FOR MORE VENETIC

LANGUAGE DOCUMENTS AND PDF DOCUMENTS SEE

author of all content except

where otherwise cited: : A.Paabo, Box 478,

Apsley, Ont., Canada

2017 (c) A. Pääbo.