One of the more interesting

Venetic archeological items with writing on it, is one of the several

found near Padua, Italy. These items appear to be memorials, and

involved a relief image accompanied by a short sentence. Located

in the Museo Archeologico in Padova, it has been assumed these items

had a funerary purpose as they are identified as "stele funeraria".

However, this may be wrong. Translations of the texts by A.Pääbo

suggest that these are actually celerations of important events. For

example he translated text associated with one of them showing several

war chariots as celebrating the departure of an army into the

mountains. Funerary inscriptions, moreover, followed a typical formula,

that these do not follow.

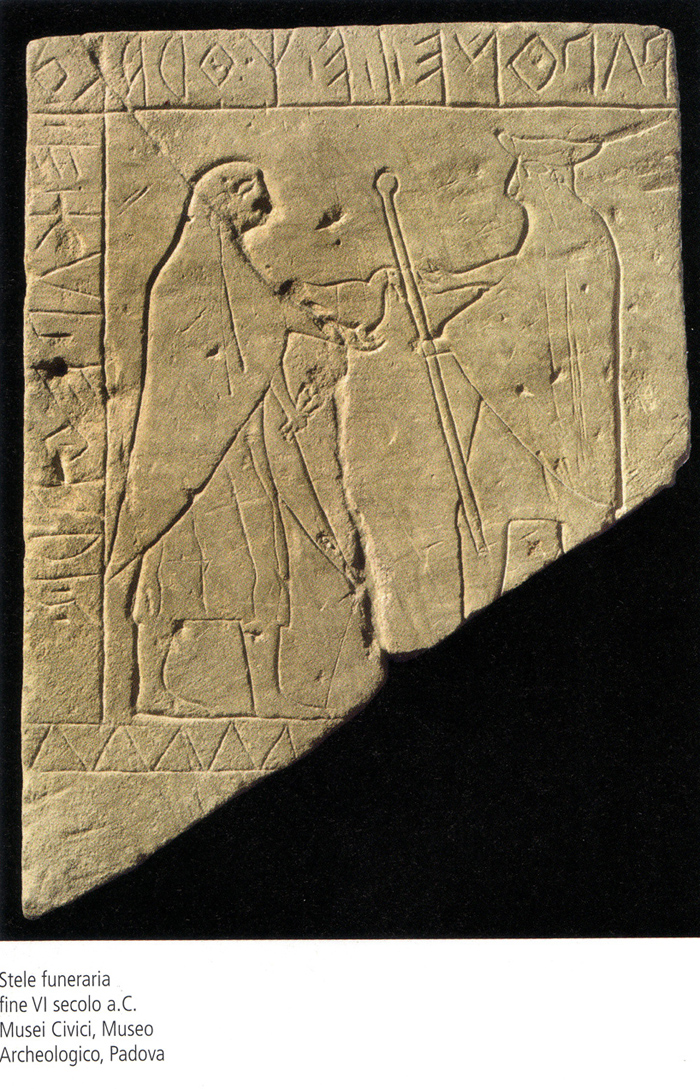

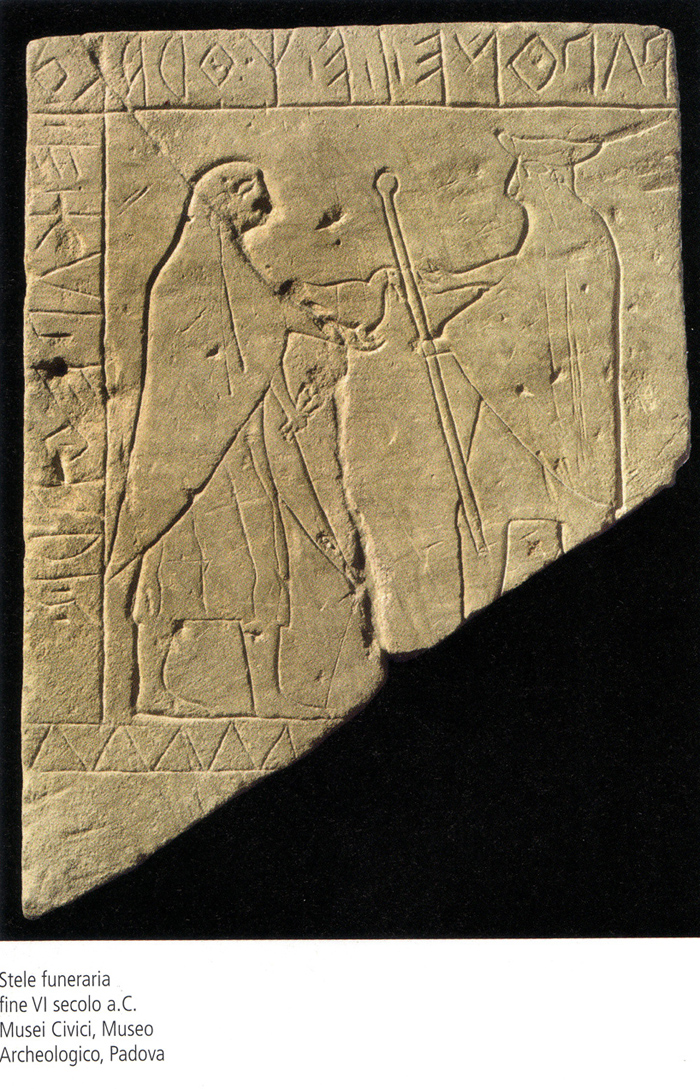

The inscription appears to caption a relief image (see photo above)

showing what appears to be a peasant, handing a duck to a

distinguished-looking man with a cane. A.Pääbo argues that this image

depicts an important 'father', perhaps a religious man that was a

precendent for the tradition of "Pope" in subsequent Christianity. The

inscription around the image, when converted into Roman alphabet from

the Venetic alphabet reads (including the dots)

pupone.i.e.gorako.i.e.kupetaris

The appearance of some of these words in other inscriptions allows us

to divide it into the following words

pupone.i.

.e.go rako.i. .e.kupetaris

Most of the inscriptions have images and messages that seem to concern

horses and travel by horses, and which feature an expression

ECUPETARIS. It has been easy for linguists who assume the Venetic

language was in a Latin-like language, to see in this word, Latin equus

for horse. However, the word appears to be tacked onto the end, and to

be something analogous to 'bon voyage' or 'have a good journey'.

Of course, it can be assumed it wishes a good journey into heaven, but

A.Pääbo believes the images celebrate a major event in the lives of

this community. The accompanying text is like a caption.

The fact that the text appears to caption the relief image, opens doors

to deciphering the Venetic without assuming any linguistic affiliation.

So far, attempts to decipher Venetic inscriptions in general has been

unable to decipher them directly, but have projected a known language,

like Latin, Slavic, etc onto the inscriptions. Most results do not fit

well with the nature of the objects and context, according to

archeologists who are more attentive to the nature of the object and

the context in which it was found. Thus, for any archeologist in the

know, the past attempts to project Latin or some other language onto

the Venetic, are not believable.

In this case, the image and text departs from the others in lacking any

image of a horse. This tends to undermine assumptions that

ECUPETARIS contains the word for 'horse', and supports the other

assumption - that it is simply a 'good-bye' or 'bon voyage'. In that

case, the image can be interpreted that the community recieved a visit

from a distinguished religious or political leader, and the visit wa

celebrated with this relief image at the time of his departure. The

duck could be a symbolic statuette, but given the peasant has fish

hanging from his belt, it is likely a real duck. In ancient times it

was not unusual that someone heading out on a journey of several days

by cart would carry a chicken or duck in a cage, to serve as a meal

along the way.. .

The ideal in deciphering is to try to interpret the text directly from

the image and context instead of forcing a known language like Latin or

Slavic onto it.. Interpreting the text directly from the image, we can

presume that the text probably identifies the actors in the image - the

peasant giving the duck, the duck, and the elegant recipient. Because

words like PAPPA and today's POPE are almost universal to refer to a

'father' individual, it is believable to assume the first word

pupone.i. refers to the

distinguished elder in the image. It is also believable that the ending

-

ne.i.

- indicates the duck is being given 'to' this person - a dative or a

similar case ending indicating the act of giving 'to' the

'father'. Secondly it is most probable that the word for

'duck' is in the sentence too because the act of giving the duck is

central to the image. We can of course consider that the word may

be something like 'gift', so we need something more to narrow it down.

Assuming that perhaps the word for 'duck' survived in languages in the

northern Italy area, .they looked at some dictionaries of languages in

the area, and found Slovenian

raca

for 'duck'. Becuse this word is not found in other Slavic languages, it

suggests ancient Veneti assimilated into Slovenians and kept some of

their own words, including

rako.

The word form also brings to mind English

drake. The word in the sentence is

actually

rako.i. and it is

assumed this is a partitive here, with the meaning 'a duck'.

That leaves two words -

.e.go

and

.e.kupetaris. Both

of these words appear often in other inscriptions. The latter

.e.kupetaris,

as already mentioned, appears often tagged onto the end, and appears

likely to mean something like 'bon voyage', 'happy journey'. The

word

.e.go also appears often.

It is most prominent as the initial word on obeliques marking

tombs. Traditionally scholars assumed .e.go meant the same as

Latin .

ego 'I', and so all

those tomb markers were translated as 'I am [rest of the inscription

assumed to be a proper name]' Of course, it is peculiar anywhere

in the world for a tomb marker to be inscribed as if the deceased is

identifying himself. Most tombstones in humankind refer to the deceased

entering an eternal sleep. Hence the common expression today of 'rest

in peace'. Even in early Christianity when Latin was used,

tombstones might have the Latin

HIC

IACIT meaning ‘here rests’. If we turn to a Latin

dictionary we find that

iaceo

is a solitary word there in the meanings given above. Most Latin words

in the similar form

iaco-

concern arrogant boasting, hurling, throwing, etc. It follows that

iaceo is not Latin but borrowed,

possibly from Venetic itself. (the Veneti predated Rome).

Thus, it is obvious that the word .e.go meant 'rest, remain',

especially since its repetition at the start of a tombstone

inscription, is analogous to 'rest' as in 'rest in peace'

But does this mean the inscription is a tombstone? No. The idea of

'rest' is not exclusive to death. We can today say 'I am taking a

rest'. Or 'let the duck rest with the father'. And that is how we

interpret the

.e.go here.

Thus the translation, developed directly from the object, is something

like:

To

the Father, let remain the duck. Happy journey!

From this interpretation, it

seems the community said 'goodbye' to a distinguished political or

religious elder visting from afar, and gave him a duck for the journey.

It is possible that giving a departing visitor a duck was a standard

practice.

But who was this visiting elder? Where did he come from? Is it possible

that in pre-Roman times, centuries before the rise of Rome, there

existed religious institutions perhaps among the Etruscans, if not

Veneti, where the religious leader was known as 'Father' and the actual

word was PUPO. This is believable, since when Christianity arrived in

early Roman times, it did not create a new institution, but continued

existing institutions. Indeed, Christianity grew in Europe, from taking

over existing non-Christian institutions. Obviously the PUPO in the

image was not Christian, but could have been an earlier religion, even

Judaism. The Venetic inscriptions themselves reveal a worship of

the early mother goddess Rhea.