supplementary articles

INTERESTING COINCIDENCES BETWEEN ALGONQUIAN, FINNIC, AND INUIT LANGUAGES

INTRODUCTION

My interest is peoples in North America who had

long boat-oriented ways of life began when I saw the use of the "INI"

word stem in the Inuit language ( Inuit means 'the people' in their

language), and in Algonquian languages. In the Algonqiuian language the

INI or INNI stem refers to 'person' as well. For example the word is

used in the name of Algonquians in Labrador and Quebed (there is the

Labrador "Innu" on the Churchill RIver, and the Quebec "Innu" on the

Saguenay River. Others have derived words for their own name

("Iniwesi", "Anishnabe", etc..) while still having the inini word for 'person, man'.

Being of Estonian descent, it resonated with the

Estonian word for 'person' which is "inimene". Also there is the

origins of the word "Finnic" appearing historically as FINNI or

FENNI. Since the "F" sound does not exist in Finnic, the initial

F-sound may be a speech characteristic caused by a strong empasis on

the first syllable, that to varying degrees produced an unintended

voiceless launch consonant - such as a voiceless fricative like F, V, H

- which arises when the initial syllable begins with a vowel. Needing

to be emphasized, the vowel is produce explosively which causes the

voiceless consonant to seem to appear. Thus foreigners hearing Finnic

words starting with a vowel, would imagine they heard an "F" (="PH").

"V", "H", "WH". For example, Romans originally used the sound "W"

for the character "V". so their name for "Veneti" peoples actually

sounded like "WHENETI". Greeks meanwhile, used "Eneti" but it would

have sounded like "HENETI" If we reverse the addition of the

voiceless consonants imagined by foreigners for Finnic words begining

with a vowel, we arrive at Finnic originating from "INNI". or if the vowel was more rounded, the "Hanti" peoples name originated from "ANTI".

Historically there were in the Scandinavian Peninsula a people

described as "Cwens" in English, or "Quans" in Swedish. These

people are identified with the Finnish dialect "Kainu" which would have

originally been "AINU". This

word now also brings to mind the "Ainu" boat-oriented culture that was

original to Japan. But in historic times, Finnic languages have been

influenced mainly by Germanic languages, and for instance an Estonian

will not say "HINIMENE" when intending "INIMENE".

A good example of how the need to emphasize an

initial vowel produced a consonantal sound can be found in "Hiigla"

meaning 'giant'. It is common to find in Estonian words needing not

just the length of double vowels but the initial emphasis, will add the

H to make the sound more explosive.

My conclusion is that a voiceless consonant in front

of a Finnic word with a strong initial vowel, is either conjured by

foreign listeners or has developed into the Finnic language from its

being too strong to ignore in written Finnic.

The presence of the INI stem in North American boat

peoples tends to suggest that all these boat peoples originally had the

same language, and that as long as they followed their unique

boat-oriented way of life, a continuous thread of linguistic descent

was preserve, even if there was much change from external influences

and invention.

If this is true, then we should be able to find more

words that have survived over thousands of years without changing too

much.

In my investigation of a Lake Superior dialect of

the Ojibwa (Anishnabe today) language, I discovered some words that are

identifiable in all the boat peoples I looked at, words with no

similarity at all, and a large spectrum in between. I will below

highlight some of the remarkably similar words. I will avoid dealing

with the in-between words, which may or may not be valid.

The reality is that words in all languages

degenerate or are even abandoned if not often used. The

remarkably similar words MUST be common words that had to be used

frequently for thousands of generations, or else they would not have

survived so long. In our study, after all, we are dealing with the

survival of words for up to 6,000 years. If we are comparing the

language with another language, these would have to be long lasting

common words in BOTH languages. As a result, linguists acknowledge the

words with most longevity would be words pertaining to family

relations.

In our investigation of the Inuit language, the

words with remarkable similarity to Estonian and Finnish were indeed

words that would have been in constant use generation after generation,

and change only slightly.

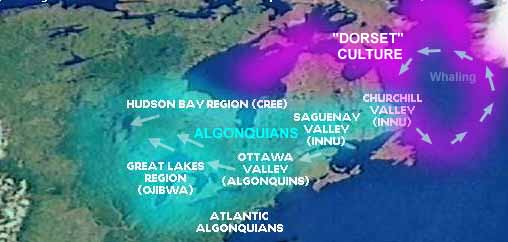

This

map shows both the wide distribution of the Algonquian boat peoples (in

blue) and arctic seagoing boat peoples in purple, that appear to have

loaned many words into Algonquian, or perhaps were first to inhabit the

post-glacial interior at a very early time. (This implies that the

Algonquian boat culture may not have developed, at least not entirely,

in North America, but practices and ideas came from the arctic seagoing

cultures.

My purpose here is to present evidence that reveals

a common origin in northern boat-oriented original peoples. See also my

other short reviews of aboriginal peoples in North American Pacific

coast. These may serve as proof that the aboriginal peoples of North

America did not entirely come by foot over the Bering land bridge. Ever

since the invention of seagoing boats, there has probably been hundreds

of crossings to North America from Eurasia (and why not the other way

too? and North America before European colonization was already a

mixing of cultures according to the strength of the immigration,

compared to the strength of peoples already established.

THE "INI"

WORDS AND WATER/SEA WORDS

Note: the Northwest Lake Superior dialect is used as it would be least influenced in recent times.

In chapter 4, I proposed that the Algonquian

indigenous peoples of the northeast quadrant of North America had

origins in the arctic peoples, such as the "Dorset" and/or earlier

culture,

who arrived in the arctic waters in skin boats since around 6,000 years

ago or more, and continued an established life of hunting whales, seals

and walrus.

They would have spoken a prehistoric language that was carried with the

expansions of the oceanic boat peoples, ultimately from origins in

northern Europe.

The first seagoing boat peoples to arrive in the vicinity

of Newfoundland would have found the rich seas uninhabited. However,

there would have been pedestrian hunting peoples in the interior. When

some of the arctic skin boat peoples

ventured further south either from Hudson Bay, or south along the

Labrador coast, they would have also encountered indigenous woodland

hunters - pedestrian and avoiding post-glacial flooded lands. In

any case, the resulting languages were those called "Algonquian" by

linguists today. The immigrants would have been free to inhabit

still-uninhabited flooded post-glacial lands, and would have

intermarried with the indigenous peoples.

The Algonquians of Quebec and Labrador called

themselves "Innu". There were the Labrador

Innu associated with the

Churchill River, Montagnais Innu

associated with the Saguenay River.

But as we moved west, the names changed a little. The Algonquins of the

Ottawa River valley today call themselves "Iniwesi" which means 'we

people here alone'. The Ojibwa peoples use variations of the word

"Anishnabe" whose meaning is

something more complex than 'the people'.

However all the Algonquins have their word for 'man, person' in a form

similar to inini. Just as I was originally drawn to the Inuit language because the word is plural for 'person' (singular is inuk) so too I was drawn to the name Innu in Labrador and north coast of the Saint Lawrence, and to the word for 'person' inini. I found it a mysterious coincidence that Estonian possesses the word inimene for 'person' plural inimesed.

The results of my investigation of similarities

between Algonquian language and Finnic language are not

earth-shattering - otherwise scholars would have noticed it earlier.

(Maybe not, since there are very few if any scholars who know a Finnic

language, who have even considered investigating Algonquian. You have

to bear in mind that my investigations arise entirely from my discovery

of an expansion of boat peoples in the wake of the retreat of the Ice

Age in northern Europe. Unless one begins to try to trace the expansion

of boat-oriented way of life, first by rivers to the east, and then

into the arctic and Atlantic oceans, the question of whether

boat-oriented aboriginal peoples also spread the original language -

which I identify with the archeologically defined "Kunda" material

culture - would not have occurred to them.

Interestingly the Algonquian peoples

pictured North America as a large turtle in a sea, a concept that would

only be envisioned by seagoing peoples accustomed to travelling long

distances in the sea. Because North America is very large, knowledge

that it is surrounded by seas and is an island, requires people able to

travel long distances along coasts and major rivers.

The following looks at some of the more significant

discoveries, according to various themes. The examples given here

are from the "Ojibway

Language Lexicon" by Basil Johnson, presenting his dialect of

north of Superior, a dialect that is unlikely to have

been subject to much influence from modern developments.

(A proper study of correspondences requires a greater

knowledge of Ojibwa than I have. Ojibwe, like Inuit, is built from

strings of elements.

There are no clear 'words' in the sense of modern

European languages having clear 'words'. Thus it is necessary to be

able to break down the words into constituent components. For that

reason it is best if the analyst knows the Algonquian language well

enough to grasp the inner composition.)

1. WATER: THE WATER-BODY: KAMO, GAMI, GEEM

One of the concepts discussed earlier is the use

of the AMA pattern to express 'water' in the sense of an expanse, a

sea. In the discussion of the Inuit language, it appeared it was found

there. Yes, we can find it within Ojibwa. For example 'he surfaces out

of water' is mooshkamo, the

word for water being expressed by I believe

-kamo. The AMA pattern is also

in gitchi/gami 'great

water-body =

ocean, sea'. The idea of AMA seems to be present in Ojibwa, in that gami

properly refers to a 'water-body, sea' and not to the liquid.

Throughout early humankind, such as revealed in

ancient Greek, the world was seen as a large sea in which all lands

were islands in it. This flat fluid world represented a mother earth

that was not made of earth, but was a sea. Hence we should not be

surprised if the AMA word form referred also the the word for

'mother'. If gami meant 'sea', then it is interesting that the Ojibwa word element for

'mother' is -geem- which is

relatively close to gami.

In Estonian the word for 'mother' is ema.

Does this

indicate a view of a large water body as mother, the same as we see

everywhere else? (Estonian ema,

Basque ama 'mother')

Thus we can here see at least a coincidence in worldview - of seeing

the expanse of the sea as the Mother Earth, except the earth was seen

as a plane of water. In ancient Greek texts the known world was seen as

being surrounded by seas. This concept may have originated long before

ancient Greece, an accumulated wisdom that developed with the expansion

of boat use, and long distance trade.

So far we have not discovered much yet. We will have more success when we turn to the Ojibwa word for

'water', the liquid.

WATER, THE SUBSTANCE: BI, BII

Although the Inuit language presents the V

sound, the Ojibwa/Anishnabe language lacks the V, and B plays the role

of the V. But neither are the V or B sound we are used to with English.

Both sound more like a slightly voiced, slightly fricative B as opposed

to the silent one. But we will write the Algonquian (Ojibwa) words

according to modern practices. I will represent it here with "BH-"

In the Ojibwa/Anishnabe language there exists the suffixes

biiyauh a verbalizer meaning

'quality character nature of water or body

of water' and bi, bii 'verbalizer/nominalizer

refering to liquids,

water'. Examples are biitae

'water bubble', biitau

'surf', nibi

'water', ziibi(in)

'river', mooshkibii 'he

surfaces out of

water'. It can be argued that the voiced "B" was the original

sound in all early languages. The Inuit

"V" and even the Finnic "V" may have originated from a softer B-like

sound that is simpler than "V". (A chimpanzee can produce such a "B"

sound, while it cannot say the modern "V"!)

Thus the original word for 'water' or 'liquid' may have sounded not

like modern Est/Finn. "VEE" but more like "BHEE" or

"WEE". Another observation is that Inuit lacks the "E" sound,

which suggests the original language of the boat people too lacked the

"E" sound, and instead used "I". In that case Estonian/Finnish words

for 'water' (the substance) would have been "VII" originally sounding

like "BHII" or "WII". It may have survived without modification in the

Finnic steam ui-

which means 'swim, float'. It all makes sense that the earlier forms of

the boat people language has endured longer in Inuit and Algonquian,

while it came under the influences of European In

GATHERING : KOOG-

Ojibwa Koogaediwin

means 'village', 'temporary

encampment'. As we saw above there was Inuit qaqqiq

'community house' versus Estonian/Finnish kogu/koko 'the whole, the

gathering'. Indeed in the Estonian landscape a common name for a

village was Kogela 'place of

gathering'.

DUALISM: GE-

We saw that the Inuit language had the dual

form, but that was not significant since the explicit recognition of a

dual form is only needed if the concept of being in a paired situation

is important. What was important though, was that it appeared that the

dual form was marked by the "K" as it is in Estonian/Finnish (example

kaks/kaksi 'two').

In Ojibwa too, the sound "G" appears to have a function similar

to Estonian at least in its commative case ('also,

too') In Ojibwa, the pronoun niin means 'I' but adding ge- to the

front as in geniin makes it

'me too'. This is analogous to Estonian ka

mina 'also

me'. It applies similarly to other pronouns.

Continuing evidence of the use of G for dual: Ojibwa reveals

a dual in the imperative, where commanding two people is marked by -G

at the end. For example commanding one person is biindigen! 'you go

inside', while commanding two people is biindigeg!. This resembles the

Estonian plural imperative, which uses the -ge ending as in mine!

becoming minge!.

ACCOMPANYING ANIMATE CREATURES - USE OF -G

Ojibwa also distinguishes between animate and

inanimate words. All nouns in Ojibwa or Cree language are animate or

inanimate and the verbs must agree. The main marker is that

animate nouns always end in G in the plural, while inanimate nouns end

in N in the plural. For example the animate inini 'man' in plural

becomes ininiwag while the

inanimate ishkode 'fire'

becomes ishkoden.

This phenomenon of animate versus inanimate can be interpreted in an

interesting way. Animate beings are things which 'accompany' the human,

and thus require the K, G sound that marks accompanying. In other words

'fellow living beings'

There is no

distinction between animate or inanimate in Estonian/Finnish, but once

there may have been, since many names of animals or trees begin with

KA, KO, KU. For example Estonian karu,

koer, kajakas, kaur, kala, kull,

kask, kuusk, etc .(bear, dog, seagull, loon, fish, seagull,

birch, fir, etc) It suggests the Finnic primitive ancestors named

animate

things with "KA" plus some descriptive suffixes. It is clear that in

the ancient past there was a more systematic use of the K sound in ways

that recognized parallelism of animate things.

THE EVERLASTING WORLD: AKI, AJI

It is significant to investigate the

Ojibwa word for 'land, earth'. As I said above, if the sea-people used

the word AMA to refer to the World-Mother, and mainly to the

Sea-Mother, then they would have had another name for the land. In

Basque (another language with deep roots), 'earth' is given by lur.

This could in my view originate from Finnic ALU-RA 'way of the

firmament, foundation'.

The Ojibwa word for 'earth'

is aki, but this word is

similar to Ojibwa words related to time!

It is not uncommon that where languages from the

same origin drift apart, each can select a version of a word based on

different stem ideas.For example in Finnish 'sun' is given by aurinko, which seems to have a connection to steam (aur-), while in Estonian 'sun' is given by päike. which resonates with äike 'lightning' so that pää äike

seems like 'the main lightening'. Two related languages can thus look

more different than they really are, when we consider that the same

idea can be expressed, and preferred, in different ways.

In this case, it looks like the Ojibwa word for

'earth' was derived from the idea of 'that which endures forever' - an

eternal constant in the environment.

This is proven if we find other words of similar form, describing aspects of 'time'.

In Algonqian, ajina 'a while, a

short time'. It compares with Estonian aja- stem meaning

'related to time'. In the Inuit examples we saw Inuit akuni 'for a long

time', which we compared to Est./Finn. aeg/aika 'time', kuna/kun

'while', and kuni/---

'until'.

Estonian has the interesting

imperative akka! meaning

'begin!'. Ojibwa has akawe!

with the reverse

meaning 'wait!' These examples of words pertaining to time suggests

that the Ojibwa word for 'land, earth' presents the concept of 'the

everlasting place'.

SPIRIT: CHII-

The Ojibwa use of CHII in

chiimaan, the word for 'canoe,

boat, water-vessel' is peculiar, but can

be explained in terms of the concept of the human body being a vessel

of the spirit -- the boat too was seen as a vessel, container, hence

the name chiimaan. One of the unique aspects of boat-people

spiritual world-view is that spiritual journeys are seen to be carried

out in spirit boats. The word for the soul-spirit in Ojibwa is chiibi

after death and chiijauk when

still alive. We can speculate on whether

it has a connection with the Chi

of oriental worldview, but for the

present, we can point to Estonian, and its traditions using "HII".

Most

recently in Estonian tradition HII was

used in the idea of grove as in püha

hiis 'sacred grove', Thus one may

wonder if it only meant 'grove'. The answer is that püha 'sacred' is

probably redundant in püha

hiis. The -S ending on hiis

suggests

it originates from HIISE, meaning 'something connected with HII'.

Elsewhere in the Estonian vocabulary one finds that hiig- means

'extreme, giant'. The concept 'big, high, great' exists in

Ojibwa also in the word kitchi.

Perhaps there is a connection between

the two CHI situations. (?)In that case the common concept in all is

'extreme'.

To continue the quest for coincidences, the

following are a sampling of words in no particular order, that resonated with Finnic (Finnish and/or Estonian were used.)

FOG OR HONOUR - AWUN, AU-

The Ojibwa word awun 'fog' is interesting

because the Algonquians had the practice of the sweat lodge, which in

Finnic is called sauna. In

Finnic the word fails to break down, other

than au means 'honour'; but

if we assume auna is 'fog',

then the

initial S would suggest 'in the fog'.

FALLING - KUKA-

An interesting Ojibwa word that used the word

for 'water, surf' is kukaubeekayh

meaning '(river) falls'. This word

compares with Estonian/Finnish kukuda/kukua

'to fall'. Plus add vee 'water' . So in Estonian one can say kukuv vee-. 'falliing water'. Also kukozhae

'ashes, cinders' may reflect the same meaning of falling. An Ojibwa

speaker can tell us if the implication in the kuko- element is 'fall'.

BONE - KUN

Ojibwa kun means

'bone', and it compares with

Estonian kont 'bone'.

LUNG (SWELL) - PUN

Ojibwa pun means

'lung' which reminds us of

Inuit puvak 'lung' which

connects well with Estonian puhu

'blow'. Ojibwa puyoh

means 'womb', which reminds us of

Inuit, paa 'opening',

Estonian poeb 'he crawls

through' Est/Finn

poegima/poikia 'to bring forth

young'.

FEMALE - NOZHAE-

Another Ojibwa word element with coincidences in both

Inuit and Estonian/Finnish is -nozhae-

'female'. We recall Inuit

ningiuq 'old woman' and najjijuq 'she is pregnant'. These

compare with

Estonian/Finnish stem nais-/nais-

meaning 'pertaining to woman,

female-'. The Ojibwa nozhae

is very close to Estonian/Finnish

nais-/nais-, and with exactly

the same meaning. Estonian says

naine for

'woman', genitive form being naise

'of the woman'

This is a word that can have such common use that it

could survive with little change for many thousands of years.

FATHER - -OSSE-

Another word that would have endured for thousands of years, is a word for 'father'. In Inuit we found the word for

'father' to be

ataata. However the common

Estonian word for 'father' is isa.

This is

reflected in Ojibwa -osse- 'father'.

TREES - METI-

In Ojibwa we have the following referring to

trees: metigimeesh 'oak', metigwaubauk 'hickory', and metigook 'trees'.

In Estonian/Finnish mets/metsä means

'forest'.

TO SELF(Reflective) - ISS, IZ, IZO

Ojibwa iss,

iz, izo is a verbalizer, reflexive

form, indicating action to the self, to one, to another. This compares

with Estonian/Finnish ise/itse

'(by) self'.

TO GO - KAE

Ojibwa kae

is a verbalizer that makes nouns

into verbs. Can be compared to Est/Finn. käis/kydä 'to go, function'.

There is something similar in Inuit.

INSIDE - SSIN, ASSIN, SHIN

Ojibwa ssin,

assin shin is a verbalizer

meaning to be in a place. This compares with Estonian/Finnish cases and

words that use -S- and denote a relationship to the 'inside' of

something. For example Estonian says tule

sisse to mean 'come inside.'

Note that we found that Inuit too employed "S" to convey the idea

of 'interior'

ALL - KAKINA

Ojibwa had kakina

'all' which compares with

Estonian/Finnish köik/kaikki also meaning 'all'.

BUTTON - NAUB

Ojibwa

naub or naup means 'lace, string

together, connect, join, unite', and

Estonian/Finnish nööp/nappi

'button'.

ROCK (HARD OBJECT?) -ASIN

Ojibwa asin means

'rock', which compares with

Estonian/Finnish asi/asia

'thing, object'.

SEAGULL - KAYASHK

Ojibwa kayashk

'seagull' corresponds to

Estonian kajakas

'seagull'. This is an almost exact parallel. Is it possible that in

their seagoing days, seeing seagulls was important - a sign they were

close to land, and the importance of the bird ensured the word would

endure.

CONCLUSIONS

The above selection represent very strong examples.

There are of course many borderline examples whose similarities are not

perfectly clear, unless a more comprehensive analysis is pursued. There

is of course a balance of words with no resonances at all with either

Inuit or Finnic, that have evolved through history, or arrived from

other languages.

But in general, the above examples seem to confirm

immediate cultural connections to the Inuit of the North American

arctic, and indirect connections going back to northern Europe many

thousands of years ago..

<<<BACK

author: A.Paabo, Box 478,

Apsley, Ont., Canada

2018 (c) A. Pääbo.