DIALECTIC

SUBDIVISION OF ALGONQUIAN BOAT PEOPLES ACCORDING TO WATER BASINS

IN EASTERN CANADA

The

following are some of the

mistakened beliefs I have found among traditional linguists, which I

have

encountered when investigating this subject. It is not unusual for

fields of

science to hold onto ideas that are old

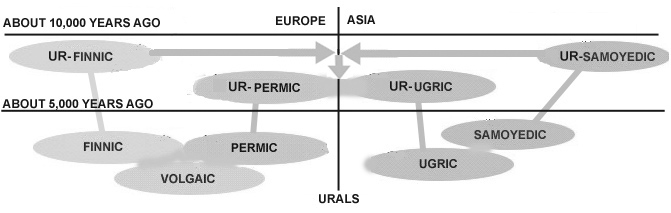

but entrenched and difficult to displace. The Figure below

presents a

modern version of the original theory when almost nothing was known

about the

early circumstances in northwest Eurasia, nor

even

linguistics itself. The linguists simply adopted a new methodology and

proceeded in the vaccuum of information of the day. It is a model that

today

could be created by a schoolboy or schoolgirl. It is about as antique

as the

early belief that the earth was flat. And yet there are still some

misguided

linguists who still follow it and defend it

In 2017 I had a lengthy email debate

with a hardcore defender of the archaic theory, and learned a great

deal of how they justified their position in continuing to follow it.

The following are some of the beliefs, some obviously ridiculous and

defensive, and my responses to them.

1. THE BELIEF THAT

LANGUAGES MUST EXIST AS INDEPENDENT ARTIFACTS?

Today there are thousands of languages, but observers – especially past

linguists who have studied the large numbers of languages in North

America at the time of European contact – have noted that similar

languages sometimes differ slightly and are dialects to each other, and

sometimes are so different that it is difficult for one to understand

the other. This is the result of the fact that languages are not

distinct tools, artifacts, with an independent existence, but that

languages in reality exists in a fluid state, often part of a continuum

of changing – converging in some ways, diverging in others, from their

prior form or from nearby related languages. Humans in the natural

state will generate a continuum based on a single language that changes

dialectically in such a way that nearby dialects are close to each

other, while dialects far away can be so different as to be regarded as

related languages rather than dialects. In the natural state,

therefore, there is a single language with dialects developed from

patterns of contact – much contact causing dialects to resist change,

little contact allowing the dialects to be more easily changed.

What we know as “languages” are the consequence of dramatic changes due

to some external factors causing those dramatic changes in a continuum.

The most common natural factors causing the dramatic changes, and even

sharp discontinuities, were geographic barriers or boundaries. For

example, originally there was a continuum of a single Finnic language

going up the east Baltic coast, that varied dialectically in the

fashion described above, but when it came to the Gulf of Finland, there

was a sharp discontinuity caused by the Gulf of Finland geographic

barrier. Of course to some extent, there was still some continuity with

dialects going around the east end of the Gulf of Finland.

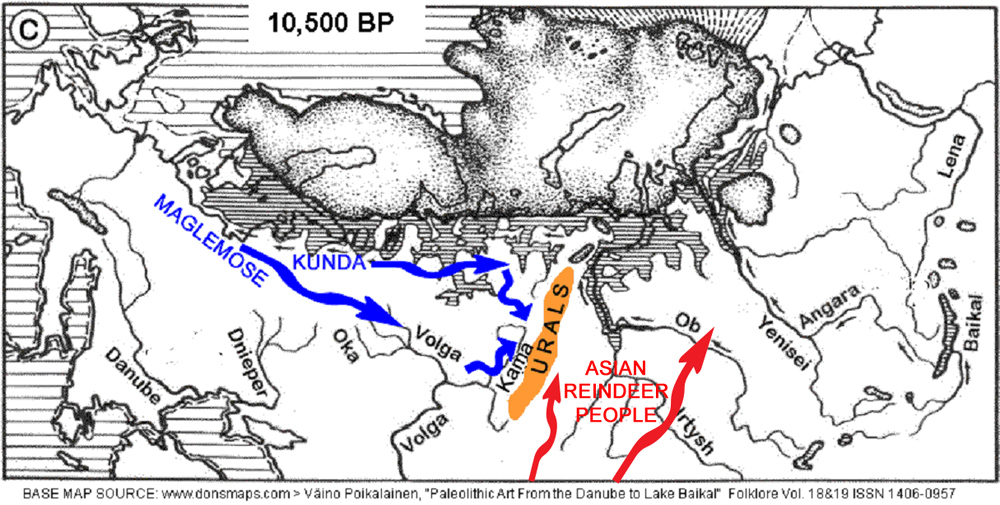

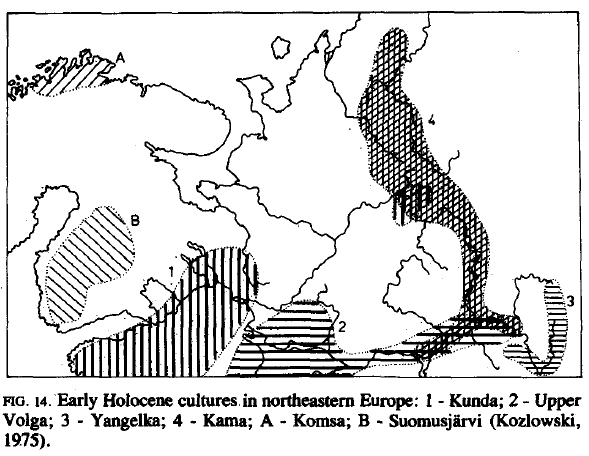

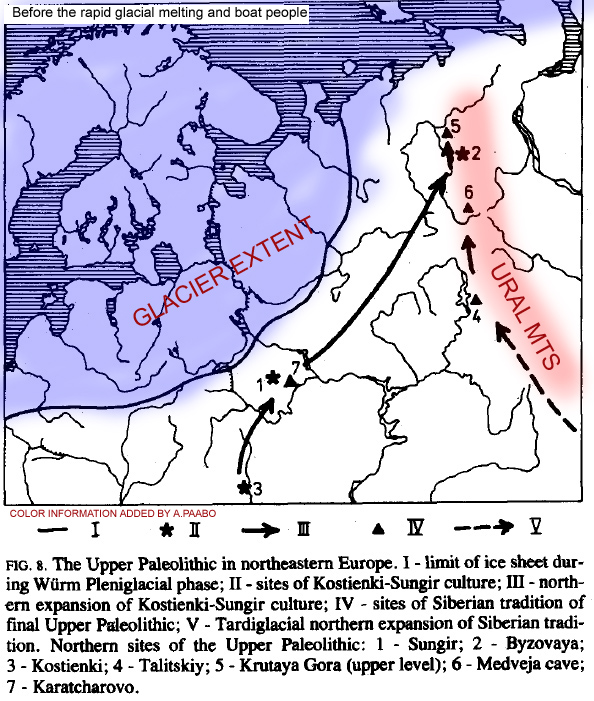

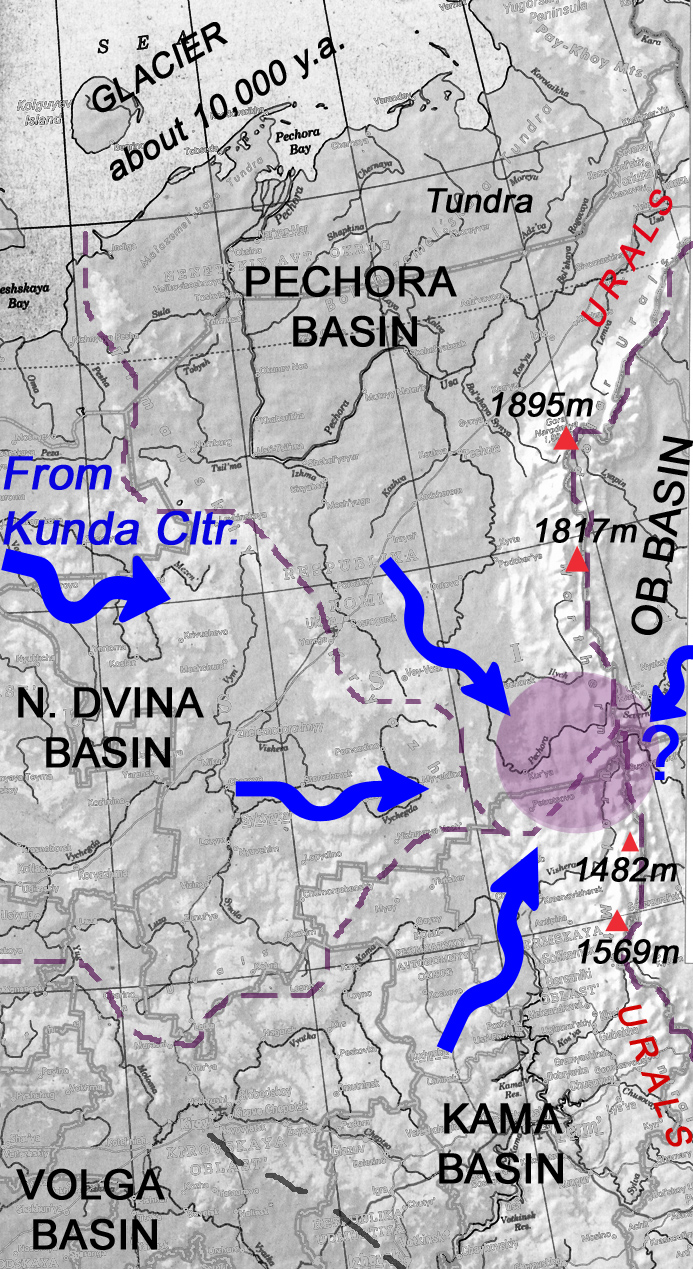

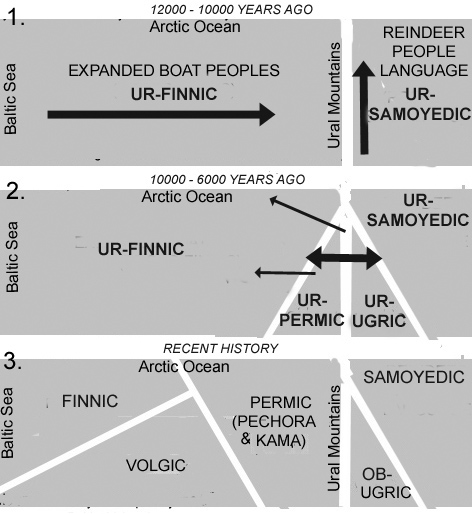

Another example is that we must regard the Ural Mountains as a barrier

causing both sides to developing linguistically a little differently

even if both languages developed from the same circumstances of contact

between the Ur-Finnic and Ur-Samoyedic languages. I have also above

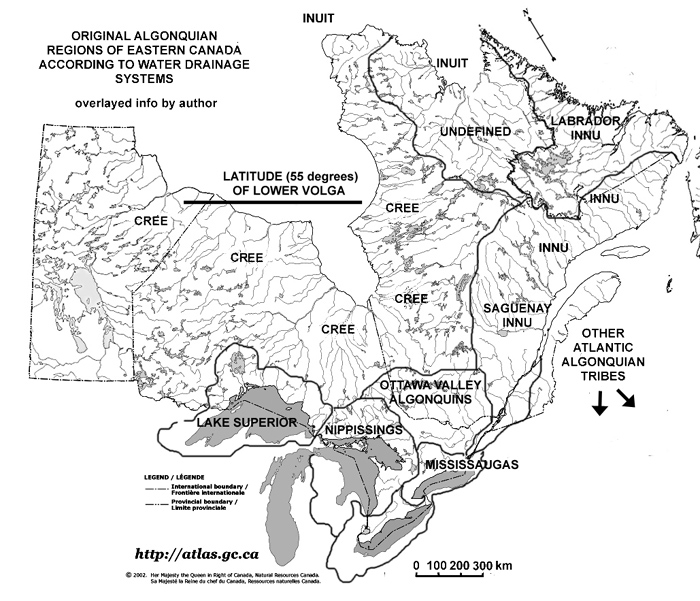

stressed that for boat-oriented nomadic peoples, the boundaries of the

inhabited water system form soft barriers to communication that caused

the dialects in one language to be different from the dialects in

another language.

But MOST languages today are not the result of natural barriers, but

the result of creation of artificial nations, and the imposition of

national languages on governed regions that originally contained the

contiinuum of a single language. And that national language was based

on the language of the strongest group.

That means when linguistics analyzes modern national languages, defined

by arbitrary national boundaries, it is not dealing with language in a

pure way, and as a result the results are somewhat contrived.

Significantly when linguistics of Finnic languages jumps from Estonian

to Livonian to Finnish to Karelian, and so on, it is not seeing the

continuum, but leaping between languages that for one reason or another

have been politically allowed to survive. All the dialects that

originally existed between those surviving languages are treated as if

they never existed.

But linguistics would be unable to analyze a continuum. Imagine that

the modern Algonquian linguistic divisions created by water system

boundaries, did not exist. There would be a single Algonquian language

continuum, changing smoothly from tribe to tribe (we can allow minor

steps of change from tribe to tribe), from the Atlantic to the middle

of Canada.

This is very important, because comparative linguistics would not work

on a continuum. Comparative linguistics has to deal with situations in

which an original language breaks up into two strong dialects which

then generates offsprings up to the modern day. Linguistics can only

compare surviving descendants of the original dialectic divergence.

Linguistics can only compare surviving languages. It therefore cannot

identify descendants of dialects when they did not produce descendant

languages that reached the modern day. For example if there once

existed Finnic languages say in the aboriginal peoples of Scandinavia,

comparative linguistics cannot see it. Insofar as comparative

linguistics today does not even acknowledge the possibility of extinct

languages, it is unlikely to present a true picture of language

evolution.

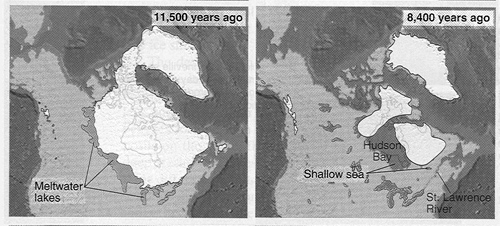

If we went back to the Ice Age, we would tend to find single languages

spread practically endlessly in a continuum. Discontinuities could be

caused by geographical barriers.. Common sense suggests that there

would have been some natural barriers too in terms of how peoples

following one way of life (horse hunters) occupied a different

environment than peoples following another way of life (say, reindeer

hunters) But there would be underlying continuity where an ancestral

people diverged between those who went in two different directions.

Thus all languages are not of the same nature and we have to be

restrained in what we conclude from them, while others may still

reflect a natural continuum among aboriginal peoples.

2. THE BELIEF THAT

LANGUAGES HAVE TIGHT ORIGINS

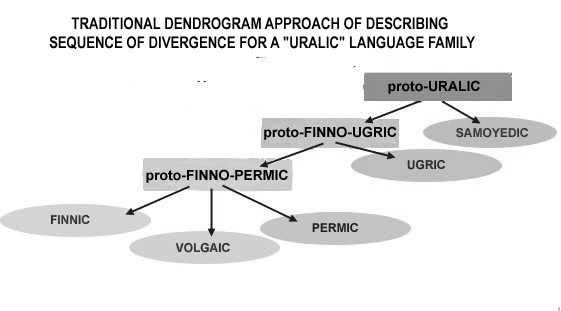

This is the silliest claim by traditional “Uralic” linguists who want

to find an original “Uralic” parent language near the Ural Mountains.

This silly idea arises only when linguistics assumes language evolves

from a group splitting off from a parent language and migrating away.

Any theory that involves migrating away, requres that the parent

language has a tight origin, If the language were widely distributed

over an entire water system, then moving away would require travelling

close to 1000km, to enter a new water system, since everyone still

within a water system would continue to have contact with the original

language. Obviously if we are dealing with highly nomadic peoples, the

correct mechanism for linguistic divergence is for the original broad

region of a single language, to subdivide dialectically for various

reasons. Since the geography is constant, the dialectic divergence will

be caused by natural continued divergence in the existing geography, or

from the inhabitants changing their way of life so at to reduce contact

throughout the original broad area. For example if members of a tribe

no longfer travelled the entire river system, but reduced their nomadic

ways to one branch of the river system, then dialectic divergence would

occur within that original complete river system.

It is important to note that when the region of a single language with

dialectic divergence (ie a continuum with some geographical influences

developing dialectic divergence) is not static. If we have

nomadic peoples maintaining a single language, over time, the language

of the whole region will evolve. What is constant is that there is

uniformity over a broad area, and then that subsequent contraction of

that broad area by further internal dialectic divergence, occurred to

that broad language at that time.

In other words, if we accept that there was once an Ur-Finnic language

that spread east as far as the Urals, we cannot claim that any modern

Finnic language looks like the Ur-Finnic language. However, the larger

the region of a single language, the more mobile the peple maintaining

that language was, the more inertia there would be in resisting

change in one location or another. Today we see the inertia in

English, where the amount of use of English causes resistance to

change. On the other hand, a local dialect in a community somewhere can

quickly change, as it has little inertia.

Thus to conclude – traditonal “Uralic” linguists have no choice but to

claim a tight origins near the Urals if they hold onto the idea of

divergence arising from migrations. A century ago, the very idea of

divergence by dialectic subdivision, was not acknowledged.

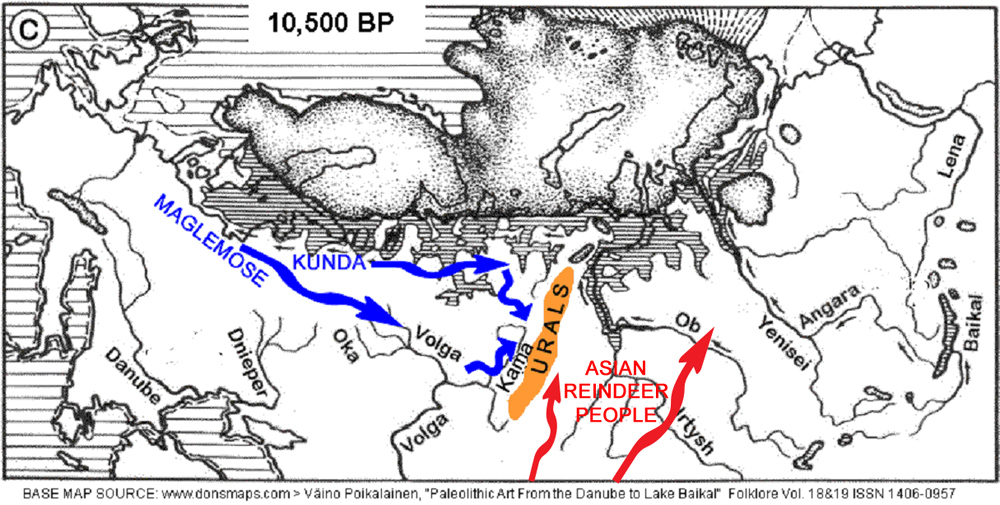

3.

THE BELIEF THAT THE SPREAD OF THE TRADITIONAL “URALIC” LANGUAGE EITHER

INVOLVED ENTRY INTO EMPTY LANDS AND/OR COMPLETELY DISPLACED THE ORGINAL

LANGUAGE

This idea is also necessary to defend the original “Uralic Language

Family” idea, in the face of increasing knowledge from archeology about

the expansion of humankind out of Ice Age Europe, a general

west-to-east expansion. Since the traditional “Uralic” theory

originally spoke about origins at the Urals around 4000 years ago, and

an arrival at the Baltic by 2000 years ago, archeological discoveries

forced the need to consider who were there at the Baltic BEFORE 2000

years ago. Scholars were confused, but generally assumed they were the

peoples historians called “Finns” or “Fenni” – people related to the

modern Saami (formerly “Lapps” and before that “Finns”). So the scholar

had to assume that the modern Finnic peoples, notably Finns, were not

descended from original people because they came from the east. But the

Saami language is close enough to Finnish to be considered related to

it.

So there existed a ridiculous situation. Theories that the arriving

Finns from the east influenced the Saami language. To summarize a whole

century of head-scratching, no evidence was found of an incoming people

from the east, displacing or even influencing any native people. When

archeology discovered that a “Comb-ceramic” material culture appeared

in the entire east Baltic with pottery styles that appeared to have

come from the upper Volga. This was enough for linguists to claim this

was the time of the migration. They only needed to push back the

arrival at the Baltic from 2000 years ago to 5,000 years ago!

Archeologists (ie Richard Indreko) dismissed the logic, saying the

influence from the upper Volga was purely a movement of a cultural

feature, not an entire tribe. There is evidence that long

distance trade, probably fur trade, began at that time. This is

confirmed by the spread of distribution of amber objects throughout the

“Comb-ceramic” area and also in ancient Babylonian tombs,

There was a spread of an influence up the Volga, but you do not require

an entire people to migrate to move something that more likely was

carried by small groups of traders, or simply carried by families to

gathering places.

It is also impossible to displace an original language with a new

language, unless the new language is very strong, expecially carried by

conquerors who kill off the indigenous peoples and force the new

language on the indigenous people. Something like that occurred in the

colonization of North America – hundreds of languages were wiped out.

But always in history, there will be remote places where the original

language endures. In the case of North America, languages have

survived, especially in the north. In the British Isles, the Pictish

language survived in the north until around the 10th century. It is

possible to think of the Saami language as a remnant of languages that

once dominated all of the Scandinavian Peninsula. Across Eurasia,

original languages can be found that have not been replaced.

Even in these cases of replacement, the new language is backed by major

powers. In order to argue an “Uralic” language completely replacing the

original language (the Ur-Finnic) we need to find the language being

spread by very powerful people bent on conquest and domination. History

shows nothing.

Therefore if there is evidence in Finnic languages of origins that

point back east as far as reindeer people, then it is more likely the

original Ur-Finnic language was simply influenced by a language that

was already Ur-Finnic at its foundations. Below we will propose that

the Ur-Finnic peoples who reached the Urals, adopted aspects of the

language of the reindeer people speaking Ur-Samoyedic, and the

resulting language, which I am calling “Ur-Permic” then began to exert

influences back east, first Ur-Permic on the original Ur-Finnic Volgic

dialect, and then the slightly changed Volgic dialect in turn

influencing the Ur-Finnic near the Baltic. The influences could indeed

spread in step by step through boat peoples according to the major

water systems. These influences would be superimposed onto the original

and continuing internal dialectic divergence, resulting in the founding

languages of the later development of the descendant languages that

survived to the modern day.

However, a century ago, linguists wanted desparately to discover a

linguistic family tree, and to use the migrations approach, and employ

the new methodology, and there was no consideration of the simple

spread of linguistic influences in diminishing degrees with

distance. ( Volgic fur traders could have been the instruments of

the spread of influences.).

4. THE BELIEF THAT

INFLUENCES – SUCH AS BORROWINGS – CAN BE IGNORED BY LINGUISTS OR CAN BE

DETECTED BY LACK OF COGNATES

One of the claims made by a traditional “Uralic” linguist was that a

linguist cannot confuse similarity from convergence of two languages

for similarity from divergence from a common parent. The reason,

was the claim, is that convergence is about borrowing and borrowed

words can be detected from lack of cognates. Original words in a

language, eventually develop words of related form and meaning, that

are known as cognates. New words borrowed from other languages will not

have existed in the language long enough to develop a history that

leads to speakers developing cognates from them.

However, if a borrowed word is very popular, then it will become part

of the language more quickly. But most of all, if the borrowing

occurred a long time ago, then it would behave like any other original

word, and its borrowed origin would not be detectable. As we see in

these pages, the contact between the Ur-Finnic boat peoples and the

Ur-Samoyedic reindeer people occurred as early as about 10,000 years

ago. That is 5,000 year before the linguistic analysis using only the

migration-divergence approach, suggests. What we have here – if you

follow the story told by archeology and population genetics – is

borrowing that took place so long ago that languages that developed

from convergence between Ur-Finnic and Ur-Samoyedic will show

similarities that can be erroneously interpreted as divergence from a

“Uralic” original language, rather than an early convergence between

Ur-Finnic and Ur-Samoyedic as early as 10,000 years ago. (Even some

millenia later, there will still be enough time for the evidence of the

original borrowing to be faded.)

It is therefore easily possible that traditional linguists mistook the

convergence between two original languages to be a divergence from a

hypothetical parent language.

Traditional historical comparative linguistics is now obsolete because

most languages evolved by convergence – often going back to the end of

the Ice Age – and yet comparative linguistic methodology is unable to

detect or analyze convergence

5. THE BELIEF THAT

LANGUAGE, CULTURE, AND GENETICS ARE INDEPENDENT AND ONE HAS NO BEARING

ON THE OTHER

Today, we can find many examples of the independence of language used,

culture (way of life) and genetics. For example we could have a

black skinned African, speaking Finnish, and practicing, say, Japaneses

culture.

But in the beginning – we have to realize – language originated as a

tool that referred to the real world with symbols in order to

communicate information. Reindeer people needed to have words for

reindeer, their gender, the landscape, the spear, how to throw spears

at reindeer, etc. Thus in the beginning a language mirrored the

way of life. Language and culture were intimately connected.

However when reindeer people adapted to using boats to hunt seals in

the sea, the words for reindeer, and hunting reindeer on the tundra

were useless. Since no language is created entirely anew, what happens

is that the useless words are rarely used and forgotten. On the other

hand a new array of words was necessary to reflect, the new way of

life. New words were necessary for boat, the sea, seals, etc, and were

invented, often from new uses for old words. Could a seal be referred

to as a ‘water-reindeer’? The harpoon used to hunt seals could be

called ‘spear’.

Many words could be kept – words for sun, earth, land, sky, family

relations like ‘mother’ ‘father’, ‘family group’. Thus if a people

inherits a language but changes their way of life, there can be much

continuity in the original language. A language is more likely to shift

the meaning of existing words to suit new similar circumstances than

invent a completely new word that never existed before.

Now, regardng genetics. We know from the behaviour of our closest

relatives, the apes, that males forming groups are rulers and defenders

of territory. New males grow up and are included in the society of

males. There is a chief, a leader, among the males, and he is

challenged by younger males who wish to take over. Humans come from the

same place – males take charge, compete for leadership, and as a whole

defend the tribe against predators or rival tribes. Indeed we can look

beyond the apes to animals that encircle females and young against an

advancing pack of wolves.

That means in the human past, males passed down the role of defender of

the tribe generation after generation. Males never departed from their

tribe They could lead the creation of a new tribe, but If a tribe

existed, its males would never leave. They would fetch their wives from

neighbouring tribes. Wives would be brought home to live beside their

mothers. ‘

For this reason the population genetics DNA marker passed down from

father to son, is revealing. It generally shows that the apparent

migration of a male haplogroup, was in fact the migration of the tribe

they belonged to. Haplogroups pertaining to females do not reveal the

movement of tribes, because the males might obtain their wives from far

away. Furthermore the daughter of the wife might then be again taken

far away into another tribe. Hence DNA in female lineage only reveal a

blurry sense of the range of a tribe over a long period. Female DNA is

most useful for permanently settled peoples where males did not go very

far to find their wives.

Thus genetics of the male lineage help us trace the migration of tribes

from the apparent migrations of their haplogroup marker. If we

can now identify the cultural development of the tribe, we can also

link the male haplogroup to culture. For example on these pages we can

determine that the N-haplogroup was originally in males of reindeer

people, therefore when this haplogroup appears in boat people, we can

infer that there were times when tribes converted from reindeer people

way of life to boat people way of life, and then from then on the

N-haplogroup was spread via male offspring, through the boat people

world, radiating from the original source location.

In terms of language, we use common sense. If reindeer people change to

boat people, and interract with them, they will have to learn the

language of the boat people to the degree of involvement. Language is

not independent of circumstances involving way or life and genetics.

Mixed marriages of course influence the use of a mixed languages, It

raises the use of the mixed language which then exerts a stronger

influence on unmixed dialects.

In general, all three parameters – language, culture, and genetics –

although independent, interract with one another in the real world, and

it is necessary to reconstruct the actual events before forming

conclusions.

Nothing is achieved by pursing each of these parameters independently

of the others since the nature of influences varies with total

circumstances.

6. THE BELIEF THAT

THERE IS NO LINGUISTIC CONTINUITY AND THAT LANGUAGES ARE CONSTANTLY

CHANGING

Since no language is developed from scratch, all language has some

degree of continuity from a language that came before and formed the

foundation for the new language. However, there could be truth that in

advanced civilizations, the language of a dominant people can displace

the language of a weaker people, and that such events can occur

alongside historical events, where one conquering people is later

conquered by another, For example, Britain was conquered by the Romans,

and most of it converted to Latin, but then five centuries later,

Britain was conquered by Germanic Saxons and Romans. But this kind of

behaviour is possible only in warring, competing, powers in

civilizations. In the case of the early languages of northwest Eurasia,

there is no evidence of any such conquering people or anyone able to

displace an original language. The fact that Finnic languages are

filled with imagery of marshy lands and boat use, do not suggest the

language came from another culture than the original Ur-Finnic of the

orignal expansion of boat people. But it is possible for Finnic to be

the consequence of being slightly changed by influences from the east

and north that originated in the early Ur-Samoyedic.

When dealing with aboriginal peoples we cannot claim any full

replacement of an original language by a new one, especially if there

aren’t even any examples of remnants of the original language in remote

places.

REFERENCES

The purpose of this article was to reinterpret the “Uralic Language

Family” theory after a century of accumulated knowledge in

archeology, and other applicable sciences. This re-interpretation is

entirely original in this article

Clark, G, 1967 World Prehistory,

Cambridge A celebrated text that summarized the accumulated

archeological discoveries up to that time. Since then the ideas have

simply been refined.

Jaanits, L. et al, 1982, Eesti Esiakalugu, Eesti Raamat, Tallinn In

Estonian, the product of Estonian archeological work during the Soviet

period, where the authors were able to access the work of other

archeology within the Soviet Union, not as accessible in the west.

Kozlowski J, and Bandi H-G

1984 The

Paleohistory of Circumpolar Arctic Colonization, Arctic 37 (4): 359-372

Article in English, where the investigation of the northeast Europe and

the Urals was only one section. I chose to use it for reference because

of this focus, and because it was a summary.

Pääbo, Andres

2002-2016 WEBSITE: The Origins and

Expansions of the Ancient Boat-oriented Way of Life: Basic Introduction

to the Theory of a Worldwide Expansion of Boat-peoples from Northern

Europe

, [

http://www.paabo.ca/uirala/ui-ra-la.html]

This is currently a layman-type site, not scholarly,

initially created for fun beginning 1998;; however the content contains

much that is original new theory from more or less raw data.

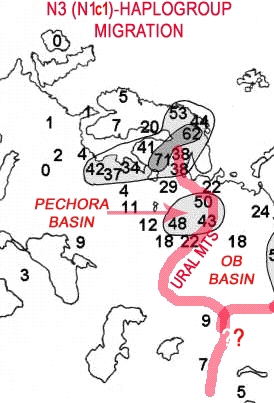

Rootsi,S., et al. 2006, A counterclockwise

northern route of the Y-chromosome haplogroup N from Southeast Asia

towards Europe”

European Journal of Human Genetics 15 (2): 204-11 Comment: This

is regarded as the authorative study suggesting the N1c1 haplogroup

migrated up the Ural Mountains and then continued west along the arctic

coast of northeast Europe to the northern Finland area, and then

diffused into the Finno-Ugric speakers from the locations of the

reindeer peoples. This agrees with the other paleoclimatological and

other facts. This association proves something that should be obvious

from the archeological/climatological story – that the Samoyedic

reindeer peoples were of Asian origins, not European.