< < <

(LEFT) AUNT VALLY FROM A NEWSPAPER

PHOTO IN 1938.

(LEFT) AUNT VALLY FROM A NEWSPAPER

PHOTO IN 1938.

My interest in art had some roots in my aunt Valley. With an education

in art in Estonia, she continued to Paris, which before the WWII was

the center of art culture in Europe. She returned home from time to

time. After the Soviet Union annexed Estonia, she could not return, so

she went to Sweden where my family had gone as refugees, and I was

born. She was

visiting in our apartment when I was two or three. She then returned to

Paris where she lived for the rest of her life. When my family went to

Canada by 1951, it just happened that my ability to draw or paint what

I saw with faithful accuracy, astounded all my teachers, and at home I

was compared to Aunt Vally, some of whose art hung in the livingroom.

With all the reinforcement, it was inevitable that it could go to my

head that I was to become an artist, and I pursued it diligently by the

time I was 10 and on towards my 20's. The following text gives some

more detail and some

illustrations.

1. 1 ARTISTIC ORIGINS AND REINFORCEMENTS

Comparisons to Aunt Vally

When I was growing up in the suburb of Toronto,

called Scarborough, it was difficult for me to avoid being compared to

my Aunt Vally. Several of her paintings were on the livingroom wall and

whenever family friends came to visit, my mother always told me to

bring out some of my artwork to show the guests, and that was followed

by references to Aunt Vally.

There was no pressure on me to become accomplished.

It appears I was naturally talented, since teachers at school marvelled

at my artistic ability since I was only 6. In fact it was the teachers

who drew my parents' attention to my talent. But once it was known, I

was supported and celebrated at every turn. I enjoyed the celebrity at

school during the years 6-10 when it came from my classmates. It made

me feel special in the context of my peers especially since I was

socially reserved - like many people are who are more involved in

observing than participating in activities. My celebrity as an

artist resulted in my father giving me money to buy art materials at

the paint store in the nearby shopping center, which had a corner with

genuine art materials. I told him I needed more brushes or whatever and

he gave me money for it.

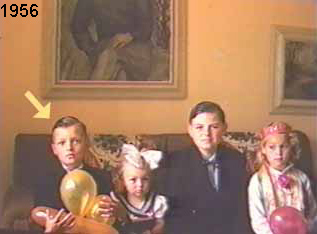

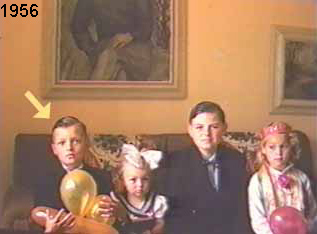

This photo shows Aunt Vally's paintings on the livingroom wall.

I am about 10 and beginning to assume the mantle of 'artist'

My talent at school lead to my school principal

informing my mother of art classes being started in the basement of the

Art Gallery of Ontario, intended for gifted young people of 10-12. Soon

I was excused from classes on Friday afternoons, to take the bus and

streetcar into Toronto to attend these two hour classes. This was

before there were subways. It took a long time to get there, and to get

back, but for a while it was all an adventure.

The teacher, coming over from the

Ontario College of Art, projected his own enthusiasm to us, and

designed each class around a different aspect of art, including colour

theory and art history via a tour of the Art Gallery of Ontario on the

floor above. He put the art I was reading in diverse books and my own

experiements, into real-world context.

This went on until I was

12, and then I was too old. But the teacher informed me of art classes

for high school students being started at the Ontario College of Art on

Saturday mornings. So from ages 13-16 I now travelled on Saturday

mornings during the school year to the Ontario College of Art, which is

around the corner from the Art Gallery of Ontario. I did not like it as

much because students were divided among the various divisions of fine

arts - painting, printmaking, etc - for the entire year. While I wanted

to paint, I found myself stuck

with grinding lithographic stones class after class, in the printmaking

class. I did get into a painting class, however, the following year.

Questioning the

Validity of Calling the Theatrical Trends and Fads in Art as 'Art'

After the classes ended, around noon, I did not want

to head home immediately, and often I explored the Art Gallery of

Ontario. I could not understand the Henry Moore sculptures, nor the

'Pop Art' that was in vogue at the time, but I remember being

fascinated by a large number of small paintings on plywood panels made

by members of the Group of Seven.

I could never understand the silly

developments in the art world, which I call 'static theatre' since that

is what they are. I was well rooted in the true tradition of art, going

back to the prehistoric cave paintings, which was to reproduce and

celebrate reality.For

example, prehistoric cave artists painted bison,

horses, and reindeer to honour them. And that motive continues in

realism - we draw or paint something because we admire them, celebrate

them. Thus if I paint the wilderness, I express a reverence to it. As

the environment became very important in our world over the years,

paintings depicting the natural environment, and wildlife, became

important in society. The kind of celebration of nature and wildlife

embodied by

the paintings of Robert Bateman could not have existed before about the

1970's. Earlier art depicting nature reflected human experience in the

trends since the Victorian Age, to wilderness recreation with canoes,

fishing etc. The Group of Seven captured the experience of the

wilderness recreationist. Animal art in the meantime captured the

experiences of the fisheman and sportsman. It wasn't until the 1970's

that nature was depicted in a naturalist ecological fashion -with the

human observer simply observing, not interfering.. While the wilderness

experience remains strong, the sportsman experience weakened

since the 1970's compared to the naturalist experience.

Realism has always mirrored what a society values.

In past history, going backwards in time, there has been a reverence

towards Greco-Roman themes that were strong during the Renaissance,

before that to scenes from the Christian Bible, before that the ancient

Romans and Greeks celebrated their mythology. I have already

mentioned the celebration of the horses, bison, and reindeer that the

prehistoric cave men worshipped as they were the source of their

survival.

Initial and Continuing

Self-Education in Art

Having come to Canada as an immigrant at the age of

5, I

didn't integrate well with other boys and girls of the mainstream

society. Thus I was pleased that I had an identity as the class artist.

Even before I was sent off to art classes in Toronto, my identity had

been established purely from classmates reinforcing my identity as an

'artist'. So when my father went to the Main Street Library every

couple of weeks - he was an avid reader, tv was very new - I went

directly to the reference section with the large coffee table art books

that could not be loaned out. When my father was through with

collecting his books, I took out three art books from the section

of books available for loaning. He checked them out with his books, and

I had three art books I could study to learn art history, art

techniques, and more. It was in these library visits that I learned

about landscape art, portrait and figure painting, artist anatomy,

animal art, how to draw cartoons, and even commercial illustration. I

was on a servious pursuit of self-education, on top of what I was

learning at those art courses described above.

In my ambition to master art, to impress everyone

all the more, I tried everything shown in the books. I sketched and

painted people, scenery, and birds. I explored cartooning, comic strips

and commercial art. Naively I thought becoming an artist was merely a

matter of education and practice. Sadly I had not considered the nature

of the art world, which by then was trying to re-define art, steer it

away from celebrating reality to shocking the public with disturning

crap shown out of context. (More about that later.)

By the time I took part in the art classes, I was

pretty well oriented to traditional realistic art. There were very few

books about 'abstract' art or the current crazy art trends. That whole

scene was baffling to me. I still view these crazy trends as temporary

cultural developments that will not last. For example, what happened to

'Pop Art'?

SOME OF MY EARLY ART

(Before the internet, and digital

cameras there were few photos. These are made from photos I found.)

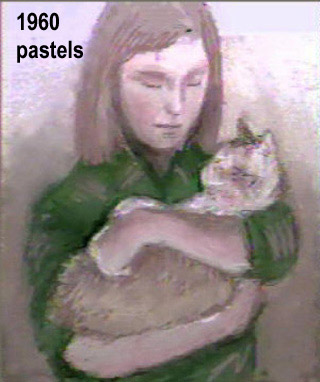

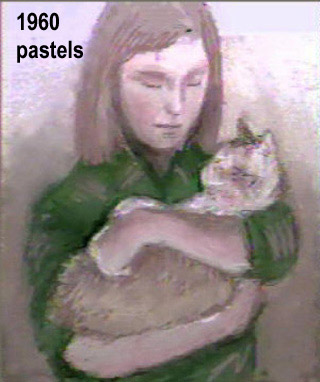

PITSY AND MONICA 1960?

I

didn't take photos of my art in those early years. This poor image

reconstructs a typical pastel painting I did of people and birds. I

also experimented with other media, from pen and ink to watercolours to

oil paints.

DEER ON OPPOSITE SHORE

After

studying books on 'animal art' I explored introducing animals to

scenes. This is a rare reproduction of one painting into which I added

a deer. This is interesting because it heralds the kind of art I

pursued in much better quality after the 1980's

ALDER BAY MARSH

1958?

One of my early paintings painted directly from nature. I parked my

boat in the bay and painted this view of the marsh.

Discovering Some

of the

Fraud in Contemporary Art

As I became accomplished in art, during my

20's I was forced now to look outside art itself, and how it existed in

the world around me.

My next challenge was to figure out how what I was

learning fit

into the current real world. At that time a great deal of fuss was

being made over the Henry Moore sculpture donated to the plaza of

Nathan Phillips Square (Toronto City Hall). Some critics called it the

'Bronze Chicken'. I still do. Let me tell you about Henry Moore - this

British sculpture claimed he was being inspired by the soapstone

sculptures of traditional Inuit peoples in the arctic. I could see

that, but that actually implied the Inuit peoples did not produce art,

but that it had to be a white man from civilization to imitate it

before it became 'art'. I would rather have seen the art establishment

commission actual Inuit artists in the arctic create large sculpures,

instead of all the pretensiousness associated with artists imitating

existing art traditions outside of 'civilization'. So the Henry Moore

sculptures and similar pretentious art for me fell in the same category

as all the 'Pop Art' and 'abstract art'. So much of it was civilized

artists trying to patronize art forms already existing away from the

mainstream art world - rediscovering what already existed, and

presenting it as something new.

My greatest revelation about the pretentiousness of contemporary

art came when I dropped in on an exhibition of art by Toronto abstract

artist Harold Town. In the middle of the gallery there was an old

cracked antique rocking horse he had found somewhere. Around the

gallery walls were interpretations of the rocking horse in various

impressionistic abstract fashion. I found ALL his artistic

interpretations of that rocking horse boring and a joke. The rocking

horse, with its peeling paint and cracked wood was the most interesting

object in the entire show!! By this time, the world had seen the high

realism art of Andrew Wyeth or Ken Danby and I think by this time

imagees by Robert Bateman were just coming to light. All these

realists would have gone the other way -instead of using the rocking

horse as a jumping off point, to produce hundreds of 'interpretations',

the realist focuses on going towards the rocking horse, going inward,

creating a painting that is more penetrating, more real than the

rocking horse itself.

That observation was what ultimately made me realise

that art can respond to reality in two ways - reacting to it,.or

converging on it. Reacting to reality with a thousand different

'interpretations', versus, taking reality and magnifying what is there

via artistic technigues, This discovery eliminated the confusion that

had haunted me in my later art education. I had experimented with the

abstract departures of reality, and felt frustrated. I recall

interpreting a scene with splashes of paint. It looked like a great

semi-abstract painting. But to me it was only the beginning of a

painting. After a few hours of capturing the overall character of my

subject, and achieving something moving, I simply HAD to spend another

hundred hours developing it into a realistic painting. I certainly

could have become a successful abstract artist since it takes a tenth

the time to create a wildly impressionistic semi-abstract landscape

painting, than a realistic painting.

In a sense converging on reality is positive, in

that the artist WANTS to capture everything that is there. It is

impossible to converge, to draw every detail, without being fascinated

with reality - in much the same way a biologist studies an animal. The

other approach, reacting to reality, can produce both positive and

happy reactions, or negative. Harold Towne's reactions were all

positive, but if the subject had been a dead fish, it could have been

negative. But just as converging on reality TENDS to be positive,

reacting to reality TENDS to be negative. Thus ultimately the matter is

not simply converging on reality, or reacting to reality, but of

celebrating (positively) reality, versus condemning (negatively)

reality. Both positivbe and negative are two sides of the same coin.

I have surveyed and come to some conclusions about

the culture of art in humankind since those early years contending with

'abstract art'.

We must not confuse traditional art, based on

celebrating

something important in the real world of our experiences, with static

theatre falsely called 'art' today, that ony lasts as long as society's

fads and trends.

For example, everyone knows how fashion (clothing)

culture is constantly changing. Well art was being redefined in a

similar way - the only different was that it was not worn on the body

by put inside a house. Culture changes, but there has to be a constant.

For example in the clothing fashion industry, the constant is that it

has to be wearable on the human body. Fashion would make no sense if it

included clothing for dogs, cats, pigs and even teapots.So what is the

constant we should find in art? Perhaps that it is 'hangable' in the

human environment. But what kind of environment? Apartment? Large

public space? A street? Unlike fashion, art cannot find a

constant in

the way it is used. That is as variable as putting fashion on a dog vs

a human. Therefore we need another constant. Is it to be outrageous? Is

it to be pleasant and uplifting?

It seems that the only constant is

that art is a direct reaction to reality. "This is how I react to

[something]-". It can be positive or negative. To gave a place in

society at large, and not just to the artist, that [something] has to

be relevant. The [something] could be Christ, to which a society reacts

positively thru its art. Or the [something] can be bison, to which a

prehistoric hunting society reacts positively to honour the bison. Or

the [something] can be the polluted environment of today to which an

artist can react negatively by depicting the ugliness of pollution -

dead fish, plastic islands in the oceans, etc - or the artist can react

positively by depicting the disappearing pure pristine untouched

wilderness. Whether a society prefers the positive (showing Christ,

pristine wilderness, etc) or negatively (showing Satan, scenes of

polluted landscapes) depends on what the public prefers. Both are

necessary - one contrasts the other - so that if we speak of

environmental art, it is wise to have the negative art shown in venues

where the public looks at it and then goes home, and the positive art

hung on home walls which are by nature positive sanctuaries. Thus

speaking of the trends in the 1980's, it was perfectly valid for the

very positive environmental art reproduced in prints to be consumed by

the general public for their homes, while the start, distrubing,

nagative reactions to the polluted environment remained in the

theatrical art world which the public consumed only for short periods

of time. There is nothing incompatable with human culture, for positive

art to be purchased by the public for their home sanctuaries while

still accepting the negative reactions being presented in the museums

and galleries. Culture is formed by the two together. It is the case in

fashion too. The fashion shows will present outlandish fashions women

will not wear in daily life, while the retail clothing stores present

the kinds of practical clothes the general public prefers to use in

regular life.

The Group of

Seven Established the Tradition of Painting the Canadian

Wilderness

In my years of self-education, I followed the art

world in the media, and I dropped into art galleries in Toronto. I

especially liked dropping in at the Roberts Gallery on Yonge Street,

where landscape realism prevailed.

Canadian nature art has at its foundation the works

of the artists who formed the 'Group of Seven'. At that time I believe

two of them were still alive. When an exhibition of new art by one of

them was mounted at the Roberts Gallery, collectors lined up and when

the doors were opened rushed to claim any work on the wall, simply

because any 'Group of Seven' art was now valuable.

I saw in the Group of Seven, my way out of the

morass of crazy theatrical behaviour falsely called 'art' (As I said

above, it should be called 'static theatre'. For example an

installation of urinals in an art gallery is not 'art', but a contrived

theatrical event designed to rob stupid wealthy people of their money.)

So I was inspired to paint landscapes of central

Ontario, where my family had a cottage, in an 'impressionistic' fashion

like the 'Group of Seven' had done a half century earlier.

But, is impressionism not a reaction to a reality?

Is ot really realism like painting the antique rocking horse above?

This question arose in my mind also when I considered where native art

belonged? I found an easy way to answer the question.

Consider portraying a person. A portrait of a

person by its nature has to converge, not depart, from the subject. A

portrait has to get closer to the subject in order to capture the

uniqueness of the person. The same would apply to painting a

portrait of a wild animal, such as a loon. The artist has to converge

on the details of the loon in order that it captures the uniqueness of

the loon, and the painting does not look like a generic dark waterbird.

This same truth applies if we portray a person in a

caricature. Caricatures can be made from a few lines, and still look

like the person being portrayed. When native artists reduce an image of

a loon to simple shapes and lines, they must still capture the reality

or else it will not be identifiable as a loon. So native art simplifies

the subject, without taking away from what makes the subject

identifiable. Some of the best exampls can be found in the cave

paintings of southern France. The images of bison, although simplified

look very real.

Thus realism is about describing the reality, trying

to capture as much of its truth as possible. It does not depart from,

react to, reality, journeying to another place.

In this light, landscape paintings that reduce a

scene to bands of paint, some lines, some textures, can similarly

capture the essence of the reality like a caricature. Even if when

squinting it may look like an abstract, it still captures the reality.

The viewer who has experienced such scenes, will immediately identify

the reality.

Bearing this in mind, I discovered that all art has

a foundation of good design. The human psychology reacts to colours,

shapes, lines, textures etc. On top of that we can add symbolism, and

narrative. Even the most high realism art has the good design

underneath that affects the viewer's emotions. For realism it is

important that the artistic technique that produces the emotions, has

to be consistent with any further symbolism and narrative placed on

top. For example, if our scene wants to produce sunny feelings, it

better use the colours and symbols most commonly generating such

feelings.

To summarize, realism is about converging on the

subject matter, trying hard to capture its essense, regardless of

whether the painting is simplified or with exaggerated detail. (The

artist has to decide what level of detail is most suited to the subject

matter.)

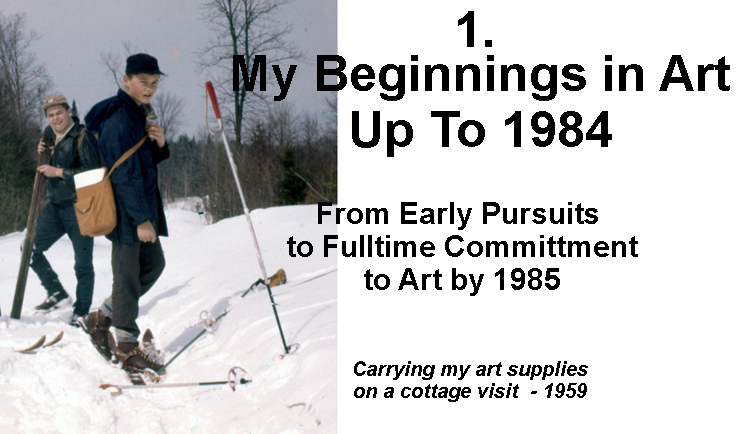

1.2

MY MASTERY OF PORTRAIT

PAINTING BEFORE THE 1970s

Portraiture was one of my earliest interests because

once I was in high school, I found I could try to make some pocket

money sketching portraits of schoolmates and in summer of our cottage

neighbours. As a result I mastered portraiture first, and actually had

a few significant oil portrait commissions in my teen years. Following

the established practices, I painted my subject in from two to five

sittings. Each sitting could be about two hours.

Thus when I explored making money from my art, I

mainly looked towards portrait sketching and painting. But by my

mid-teen years I was able to put a few landscape paintings in a couple

of places in Toronto. But mostly my display and sale of landscape

paintings was at the family summer cottage, where the owner of the

marina, Reg Armstrong, happily put my art on the wall of the store, and

made it the subject of conversation with cottagers who visited the

store. I painted small scenes from around the lake and assigned prices

of around $100 (which could be about $300 in today's money). Many were

sold. In addition, a portrait painting was put on show as well, and

from that came several portrait commissions. This activity occurred in

summers of 1961-64. I was 15-18 years old and this was a pretty good

summer business.

In general in my teenage years I had managed to have

my own business, both in summer and during the school year, making

pocket money with my art.

LANDSCAPE AND PORTRAIT

PAINTING: TWO

SIGNIFICANT TALENTS THAT LAID THE FOUNDATION

FOR MY

ENTRY INTO "WILDLIFE" OR "ENVIRONMENTAL" ART A

DECADE OR SO LATER

ARMSTRONG MARINA

FROM INSIDE THE BAY

In 1964 acrylic paints were new. This

was one of my early use of acrylic paints. The painting was done on

site. I set up in the marsh and painted while swatting mosquitoes.

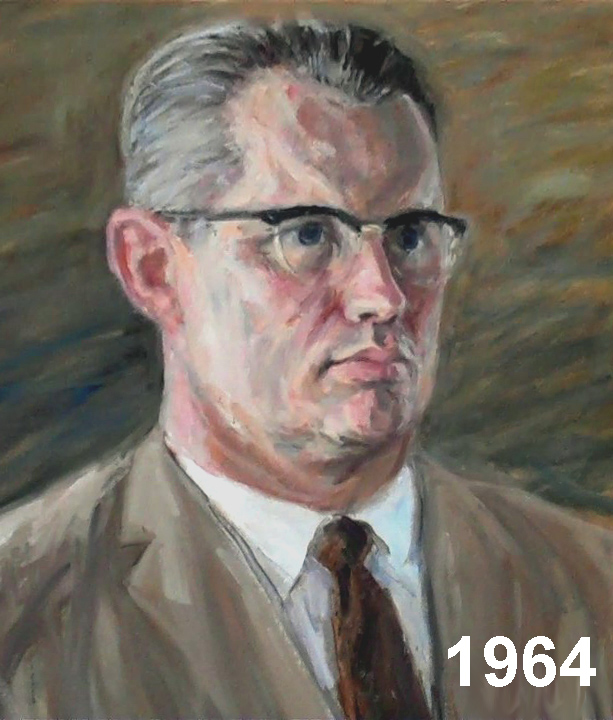

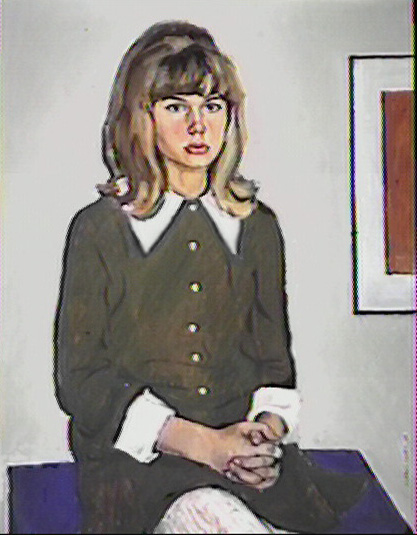

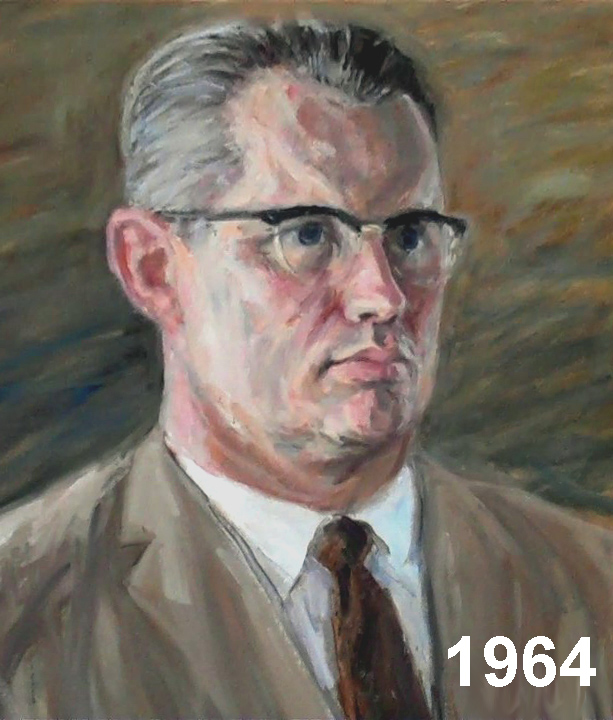

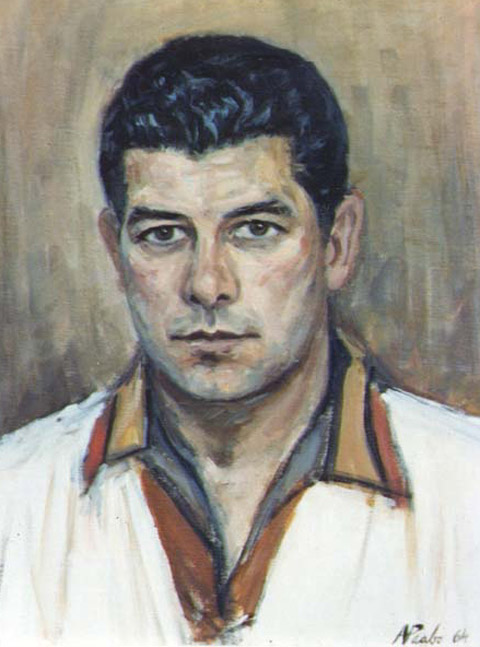

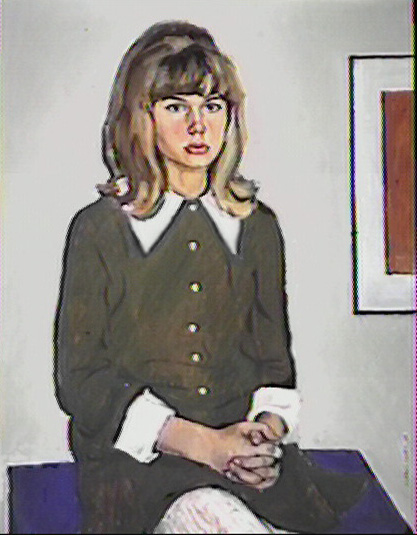

M. JACKSON PORTRAIT

16" x 20"

This was one of the more significant

oil portraits I painted in the

summer of 1964. It involved five sittings and the price converted to

today's money value was about $500. Most of my portraits to

neighbouring cottagers were charcoal sketches.

M. JACKSON PORTRAIT

16" x 20"

This was one of the more significant

oil portraits I painted in the

summer of 1964. It involved five sittings and the price converted to

today's money value was about $500. Most of my portraits to

neighbouring cottagers were charcoal sketches.

While my skills in painting landscapes was obviously

important when I expanded into the new genre of 'wildlife art' from the

1980's onward, it is not as obvious how important my mastery of portait

painting was as well. Portait painting gave me the discipliine of

analyzing anatomy and developing an eye to accuracy which preadapted me

to portraying animals. Humans, after all, are animals too. The

following shows some examples of my mastery of oil portraits.

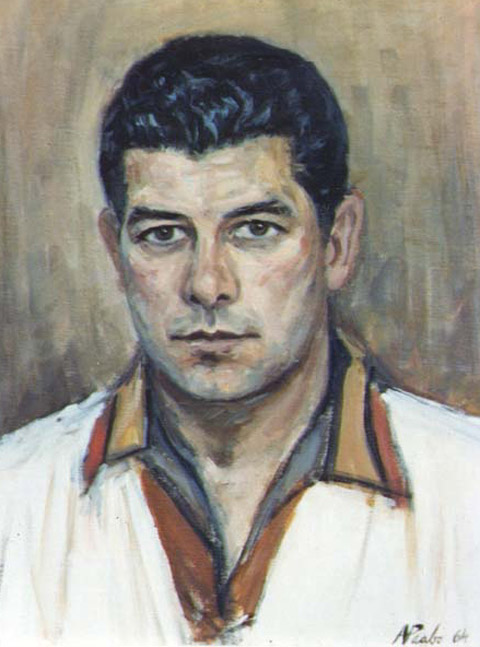

PORTRAITS

OF THE ANIMAL CALLED "HUMAN BEING"

(right)"Reg"

1964 One

of my more developed oil portraits from my teenage years shows how

accomplished I was in painting portraits by my mid-teens.

(left) "Yvonne" (my cousin) 1969 This painting, done when I was about

23, shows how

I had

mastered portrait painting. But at that time, there was no living to be

made in the art world, and I was busy trying to determine what I would

like to pursue as my 'regular' career. My pursuit of art was suspended

for the next number of years

(right)"Irene"

1969. This painting with the subject beside the painting, compares the

painting to the subject.

I already also

learned from the library books human

anatomy, and a little animal anatomy too, so that when I began to draw

and paint mainly wild animals, I already had the knowledge and

experience required. Thus when I committed myself to wildlife art

from the late 1970's I have both the skills for painting the animal, as

well as the skills for painting landscapes. I only needed to combine

the two. Earlier sections of this presentation have already showed

those results. Here I will focus on the animal portraits.

LITTLE

KNOWN FACT: HE CHARGED WELL IN THE

1960's!

Andres

P��bo painted large formal portaits already in his teenage years, and

was charging a good amount. He recalls that in around 1963 his charge

for a major portrait painting involving 5 sittings was $350, which in

today's inflated money, some 50 years later was close to $2000. Small

portraits like the head and shoulders paintings above were around $65,

which is close to $500 in today's money.

|

This education into portrait painting made it easy

for me to portray animals - to study their anatomy, capture their

character, etc. This with my dual talents of portaiture and landscape

painting, I was preadapted to immediately enter the world of wildlife

art that presented animals in their habitats, or environments with

animals in them.

1.3 MY

STRUGGLE TO DECIDE ON MY FUTURE

However, the real world does not support artists very well. As in all

fields of art, one becomes successful only when you become established

and a celebrity. Most artists had some conventional profession to make

a living, and pursued art in their spare time. The number of artists

who were famous enough to make a living from art was small.

LITTLE

KNOWN FACT: HIS COUPLE YEARS IN

ADVERTISING 67-68

Andres P��bo spent almost two

years after high school (1967-68) in the creative

department of a major Canadian advertising agency creating advertising

and several were produced and aired or published in print. That is the

origins of his advertising and writing creative ability that he applied

in the late 1990's in website design when the internet appeared.

|

That was the reality I was facing as I was ending my

high school years.

I considered what kind of profession I could pursue

to give me security. One of the obvious possibilities was commercial

art. By that time I had explored comic strips. Even though I could

never come to a decision, I went ahead to take the subjects in my high

school years required for entry into a scientific or engineering course

at university. By this time, my brother was pursuing civil engineering

at the University of Toronto. My father was a chemical engineer. So

that was my default reaction to preparing for the future.

When I actually graduated from high school, I was

determined to stay within the world of art, and one day decided to see

if I could get a job in commericial or advertising art. Filling up a

portfolio of my accumulated work, including comic strips and cartoons,

I began dropping in cold to several ad agencies and asking the

receptionists if there was an art director available to have a look at

my portfolio.

Just by chance, I walked into a major Canadian ad

agency (F.H.Hayhurst) around lunch time. Unknown to me, this agency was

booming. They were expanding. The creative director was about to have

his lunch, so agreed to see me. Taking me into his office, he went

through my portfolio, and was especially impressed by my comic strips.

"In advertisting,":he said, "we need people who are good with both

words and images" and he saw this skill in me.

Ad agencies would normally only consider applicants

with either a degree in writing, or art. Normally creative departments

contain teams of writers and artists, but it was desirable if a writer

could visualize, or an artist could create a narrative. This creative

director saw in me someone who was almost equally capable in both. So

he gave me two assignments. One assignment was to create a storyboard

for a tv commercial for Mennen shaving lotion I think, and the second a

print ad for I believe Heinz soup (or was it Aylmer).

I went home and created these ads and I either

dropped them off or mailed them to him.

As I said, the company was successful and expanding.

I was the first applicant for expansion of the creative department -

even before the offices where prepared. So he gave me a job 'assisting

both writers and artists'.

After some months, when the new offices were

finished, he gave me an official title 'junior artist-copywriter', and

I was given an office to work in. I realized my strength was more in my

being a writer who could visualize on paper, and so, I made a great

effort in creating the storyboards of layouts for my own ideas. The

regular writers had to hand their typewritten copy to their artists.

But I could do it all. I stood out, and some resented it.

I was there for two years, but while it was an okay

profession, and I could have continued, becoming an advertisting genius

in several years, it was not satisfying. Gradually I was exploring

other opportunities. For example, I was considering architecture.

Architecture calls on creativity. There was also the reality that my

brother and both parents had graduated from universities.

LITTLE

KNOWN FACT: PROFESSIONAL ENGINEER

(ONT) IN 1983

Andres

P��bo enrolled in the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering at the

University of Toronto in 1970, and pursued civil engineering, building

science and planning division, until graduation in 1974, and then

worked in various capacities in the general area and the final firm he

was at, got him certified as a "Professional Engineer" Province of

Ontario Canada. HIs early fondness for painting nature, plus a

recession and unemployment was the stimulus to give it up to become a

poor 'wildlife artist' in the wilderness of Central Ontario.

(There

were several invitations over the next years for him to return to

engineering-planning, but he turned them down citing his need to see if

he could make it as a wildlife artist.)

|

So after a couple years I departed from the company

with the intention of studying at the University of Toronto. Finding

the first year of the U of T school of architecture repeating the art

education I already had, I investigated the nearby Faculty of Applied

Science and Engineering. I would learn the engineering side of

architecture, I told myself, and then combine it with my creative side

to end up as an architect.

Later I would discover that few buildings are designed

creatively, Most building design follows standard designs and

techniques - because it is cheapest - and I would not find any

creativity in that direction. Thus I abandoned the plan of designing

buildings, and as I completed my degree in civil engineering, I steered

myself to the new field of urban plannning and design.

After graduating I began searching for something

creativet in the working world. Eventually I arrived at urban planning

and design, achieving the title of "Jr. Planner-Engineer" and learning

all about the world of zoning bylaws and urban planning. I became a

registered 'Professional Engineer" in the Province of Ontario.

1.4 A POSSIBLITY SUGGESTED BY NEW

ENVIRONMENTAL ART TRENDS

Meanwhile, there was a significant development in

the world of art. An artist named Robert Bateman was creating realistic

paintings of environments and animals. These images were

published as limited edition lithographic prints and were all the rage

in North America. This was a new kind of portrayal of animals and

nature from a naturalist angle. All former illustrative art depicting

animals were geared to sportsmen - showing bucks on hills waiting for

the bullet, or a large fish waiting to be hooked. Robert Bateman's

naturalist images were appealing to anyone interested in nature. It was

about this time too that 'environmentalism' was growing. His images

came along at the right place and time. Furthermore, Bateman aspired to

traditions of realism. He had like me once investigated the 'Group of

Seven' and tried impressionistic landscapes. He too, had to find a

regular profession to make a living. (He became a school teacher.) and

was not able to pursue art full time until he was successful.

So I think to myself - 'that is what I always liked

to do!' I saw in his work an opportunity to not just return to art, but

also possibly being successful. The limited edition lithograph

phenomenon was so popular that artists capable of creating the

naturalist paintings with the appealing narratives could publish

limited edition offset lithograhic prints and distribute them to the

same outlets that were handling the Bateman prints.

But I needed a push to embark on this new direction.

That push came from the economic downturn of the early 1980's. It was a

recession that saw the planning consulting firm for which I was working

stumble along with limited staff. During this time, my parents having

passed away, II became owner of one of the family cottage properties.

From 1976 onward I used every weekend or vacation opportunity to go

there and adapt it to become my studio. I was already beginning

to enter this new world of wildlife art before the 1980's. By 1983 I

was creating some major paintings like the one in the photo below,

which I aspired to eventually turn into a limited edition offset print.

Essentially I began painting traditional landscapes

in more detail, and

fitting appropriate wildlife into the scene. I sold them at art

festivals, and when I managed to have some significant images

published, I began advertising those images and distributiing to

framing shops, etc, who were interested in this new kind of art.

(Framing shops had good business in framing up the limited edition

wildlife art prints in those days.)

Finally the company for which I worked closed down,

and

I was faced with two options - to find another job in the planning

field, or to make my artistic pursuit fulltime. In 1985 I gave up my

Toronto accomodation and began to live

full time at my cottage to do it fulltime. I realized that if I didn't

I would always wonder if I would have succeeded had I done so. So the

attitude I had was that at least if I didn't succeed to make a living

this way - albeit at a much smaller income than I was recieving as a

professional engineer - I would have been happy that I tried.

Some

Early Paintings from around

Early 1980's before I committed to this Path full time

ANTLERS IN THE MOUNTAINS

ANTLERS IN THE MOUNTAINS

This is another major painting, this

one visualizing a concept that came to me from a photo in a magazine

showing antler-like snow in the background mountains. This was a large

painting dated to 1982

SHORE ROCKS

SHORE ROCKS

1982

This

is another painting from my early work, done I think as early as 1981.

In this case, I was exploring how naure could be the source of

interesting designs. Although I added a loon, it lacks the narrative

with the animal that most people like.

FIRST VERSION OF UNDER NORTHERN SKIES

1983 36" x 24:

This painting from 1983, is my first version of depicting an ominous

winter scene on a lake, which adds to it a line of wiolves. While this

sold well, I saw ways to improve the design, from adding a foreground,

to tightening up the line of wolves. To see the final version of 1993,

which was finally published as a limited edition, see the section of

wildlife or on prints.

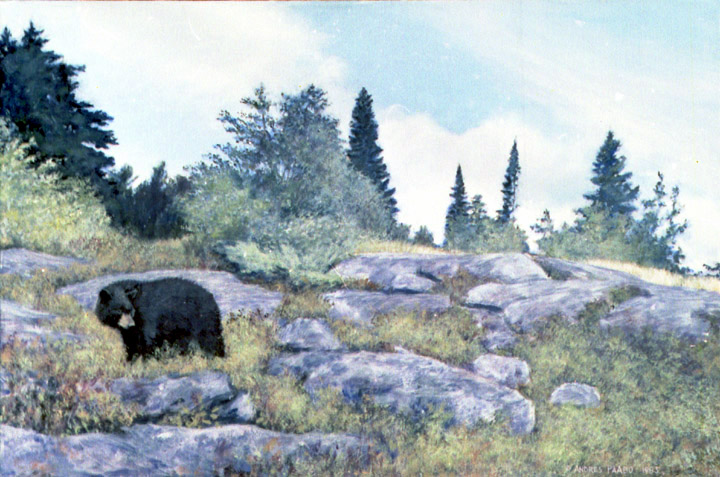

BLUEBERRY HILL - BLACK BEAR

This

is another early painting, I believe dated to around 1983. It is

large and on canvas. Purchased by the Budds, it was loaned out, and the

person who loaned it has kept it whether from a misunderstanding or

some other reason. Contact me to resolve the issue if you know of its

whereabouts.

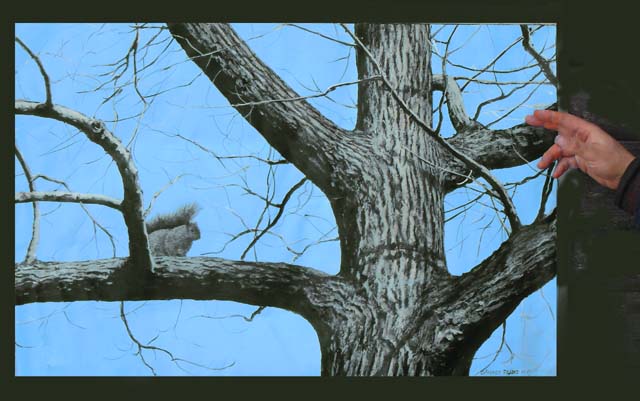

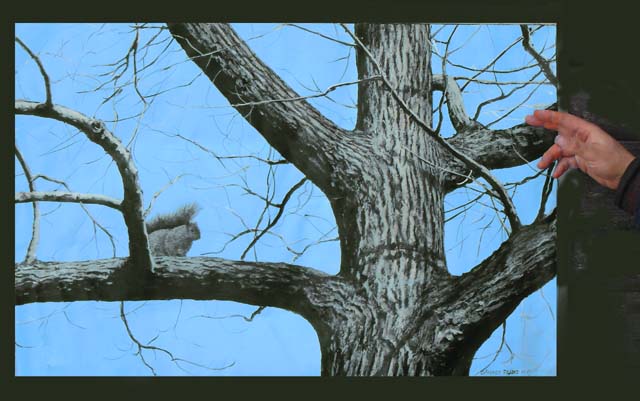

HOME SWEET TREE

1980(?)

One of my earliest paintings - from about 1980 - that explored creating

a design using natural subject matter and then turning it into a

narrative involving a squirrel. This was inspired by trees and

squirrels in Queen's Park, Toronto

OSPREY BAY 42" x 28" AROUND $1700

OSPREY BAY 42" x 28" AROUND $1700

This was an ambitiouos attempt to describe a common event in Alder Bay

- ospreys landing in the water and pulling up a fish. This is a very

large painting as the hand indicates. As I will mention later, large

paintings were difficult to sell because most people do not have the

wall space for large paintings.

SPRING CHIPMUNK 30"x 20"

This

painting was inspired by a log I saw beside the road I walked to

reach the marina. Spring was arriving and snow was melting. Chipmunks

might emerge to see if the ground was clear of snow anywhere. Since

chipmunks feed off the forest floor, this use of a chipmunk might be a

little contrived.

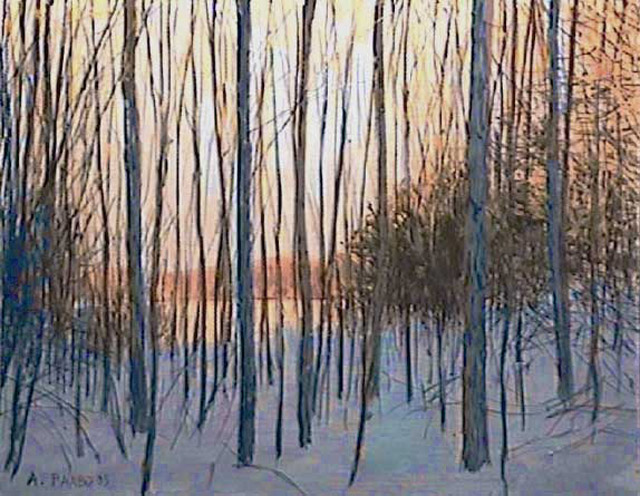

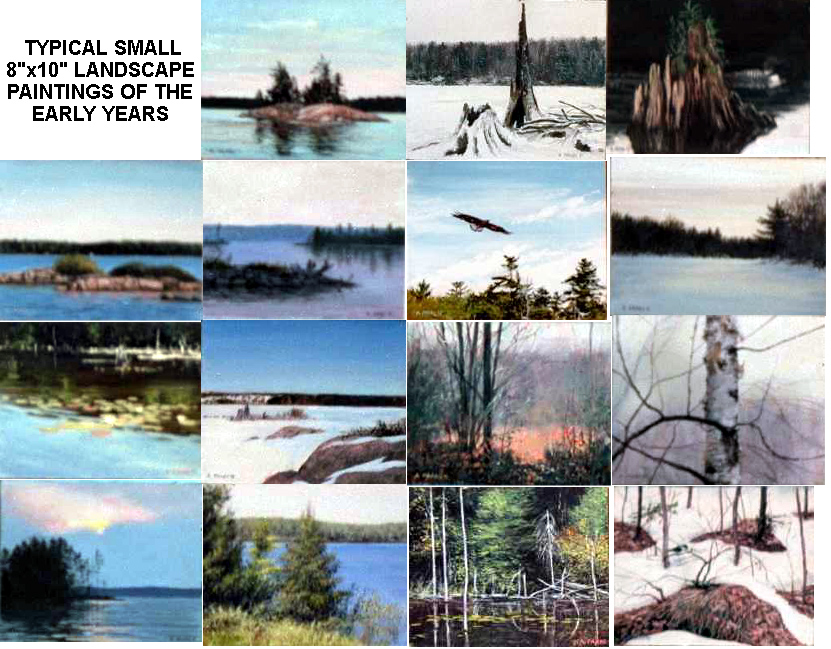

Typical Small Landscapes from Before 1985

Since I was already accomplished in painting quick

landscapes for an affordable price, and they sold well, and they were

part of studying subject matter in planning more serious paintings, I

did not cease creatiing them - expecially when I continued to find

people around the cottage country still liked them. Here is a selection

of small paintings from around 1983-4. See in later sections for small

paintings done in later years.

Some

typical exampes of the kinds of

landscape paintings I created in the transition period - 1984-1985 - to

sell to the general public in and around my cottage/studio. Some of

these paintings might be from a little later. The images are of two low

a resolution to see the dates on them.

SEE LATER PAGES FOR BETTER PHOTOS OF LATER SMALL PAINTINGS

Some of these examples above might date to a bit

later than before 1985. There was never a sharp transition like there

were with devoting to wildlife art. The trouble in the 1980's was that

there were no digital cameras, and to take photos of art, one had to

set up the art and take traditional film photos, then get them

developed into prints for great expense and discovered half were off.

Therefore I hardly ever photographed the quick small landscapes.

But a couple of times I lined up small paintings, and took a film photo

of about 9 in one photo, just to get a record. This mosaic is created

from a couple such photos. In the next stage, I was able to take

digital images with a camcorder connected to a digitized connected to

the Amiga computer. This allowed me to get low resolution digital

images at no cost and which I could process in the computer. But sadly,

I have very few photographs from before digital cameras appeared.

Therefore the images shown here tend to be of better resolution and

greater quantity for the years 1995 onward in the next section of this

biography.

Thus to summarize - I continued to create small

landscapes when the mood struck me, even as I ventured into large

landcapes on canvas, and landcapes involving wildlife. The reason was

very simple - the large canvases had to be priced several times higher

than the small landscapes and that constricted my market. Therefore

when after 1985 I exhibited at art festivals, I made certain that half

of my paintings were small landscapes. The serious large wildlife art

tended to mainly demonstrate my capability, and promote sales of

limited editons, and if some wealthier art enthusiast came along and

bought the masterpiece, well that was a bonus. But clearly before the

limited editions became popular, and after the limitied edition market

declined, the small landscapes were my bread-and-butter.

1.5 COMMITTING TO WILDLIFE ART

AND LIMITED EDITIONS BY 1985

By the summer of 1985, being unemployed because of a

recession

occurring in the early 1980's. and having now managed to place wildlife

paintings (such as the early Under Northern Skies) into galleries, I

made all the arrangements necessary to move permanently to the

cottage/studio, and give up my Toronto address. Even though it might be

a struggle, I realized I had to at least try, or else always wonder if

I could have been able to make a living with art, instead of continuing

on a path in Planning.

My first year living in the north Kawartha

wilderness was a challenging one. I had not experienced an entire

winter there - I was situated about a half a kilometer from where

snowplowing of roads ended. Every day, I walked to the marina and

interracted with its owner, Reg Armstrong, who was also in the habit of

living there through the winter, whereas cottagers only came there

sporatically on weekends to run their snowmobiles.He had plenty of food

in his store, and he was happy I was using up his old inventory.

I discovered early that I didn't have enough wood

for heating, and I had to adopt a habit of looking for standing

deadwood, cut it down, and drag it home, where I cut it up in the

evening. I burned it in the cookstove left over from my early days

being a cottager. It had an oven, and I learned to make bread, since

Reg lacked fresh bread, but had flour.

The real challenge would come in the spring, when it

was necessary for me to set out making contacts with art galleries and

registering in art festivals where I could sell the art I had created

through the winter. I already had some contacts from the previous years

where I had divided my time between here and Toronto. While creating

the paintings were challenging, it was actually the easy part. The

difficult part was to make a living from it. The various art shows -

usually weekend shows in different parts of Ontario - sold booth space

in which to hang art or crafts to sell. Because at this time the

wildlife art and limited edition trend was at its peak, these art shows

were often oriented to wildlife. The most important one to me, as it

was only 45 minutes drive away, was the Buckhorn Wildlife Art Festival.

At its peak it was attracting wildlife artists from all over North

America, and also wildlife art enthusiasts. I was in that festival I

believe by 1986 and it became an annual habit to appear there.

But there were many other shows, some smaller, some larger, some

enduring and some lasting only a few years. Between becoming known via

the shows, putting art into galleries in Toronto, and marketing my

limited edition, I was able to survive okay in the decade from 1985-95

to being one of political movements in the world of art experts who

couldn't paint, or art sellers who could not do anything more than

pursue money. It was a world in which outrageous crap could be deemed

'art' and wealthy people conned into spending large amounts of

money

on it. I recall quite a few decades ago, a news item in which

renovators of a small New York gallery had left a pile of bricks in the

corner of the gallery, and visitors had taken it to be a work of art

with a profound statement. Well I was not surprised when recently many

decades later, a similar news item appeared - unfinished renovations in

a gallery being assumed to be art - to give readers a chuckle.

Today

any stupid thing can be called 'art' as long as it is taken out of its

normal context - such as putting a pile of bricks indoors - and someone

generates some profound meaning to it. I sound cynical, and yes, it was

this cynicism that made me steer away from art as I approached my 20's

and saw what the art world had become. As I will describe further in

this autobiography, I departed art to pursue something more realistic

and practical - urban -planning and engineering - until the rise of

wildlife/environmental art distributed via limited edition reproduction

marketing that bypassed all the institutional a-holes in the art world

that sought to control how the public saw and consumed art. Thus from

about 1980 for a decade or two, I was re-inspired towards art.

The

above was written

in March 2016 - Andres P��bo

contact: A.Paabo, Box 478,

Apsley, Ont., Canada

2016 (c) A. P��bo.

(LEFT) AUNT VALLY FROM A NEWSPAPER

PHOTO IN 1938.

(LEFT) AUNT VALLY FROM A NEWSPAPER

PHOTO IN 1938.