< < <

My paintings "Under Northern Skies" and "The Teaching Rocks" became

lmited edition prints in the early 1990's but the original public

excitement about wildlife limited editions was lessening..We have to

admit that the limited edition reproduction was a new thing - allowing

anyone to have a highly illustrative nature image on their wall. But

when everyone had decorated their walls and there was no more space

left, they had no reason to buy more. The limited edition print

phenomenon was not one that regenerated itself regularly like popular

music and film. There was and is no culture of 'hits' motivating people

to replace their old prints with the new 'hits'. So many people loved

my prints but said 'our walls are full'. It was not

economic for me to pour money and energy into making and marketing

prints. I never enjoyed the marketing side of it anyway.I would rather

just create the art. I however kept my prints, and continued

to deal with them as circumstances allowed, carrying them alongside my

regular art. I returned to only creating original art. Still, I could

not

create large serious paintings that took weeks or months and had to be

sold for thousands of dollars - there simply weren't many wealthy art

collectors!. But I found great

interest - as always - in my quick small 8"x10" landscape paintings of

the kind that goes back to my teenage years. Public interest in them

has never wavered. This then became my new bread-and-butter, while

continuing to also make serious large paintings and hoping to

find buyers for them. This Part 3, covering 1995-2005 (more or less)

will present some of the larger landscapes, and plenty of the small

landscapes .

I found additional income in website

design. With a commercial art and advertising background going back to

1968, I was preadapted to take on both traditional brochure and

advertising design, and the new website design as the internet and

worldwide web emerged in the late 1990's. I was excited by the creative

opportunities and learned html and javascript coding (There was no easy

web design software back then) Meanwhile, in my

spare time, I exploited the internet to both do

scholarly research. My researcj interests are rooted to when I was a

university student

and had an interest in the little-studied subject of the prehistory of

northern Europe..

From about 2002 I developed a theory of the prehistoric development of

boat peoples, who as whalers, spread around the arctic. This had

implications on linguistics too, as the aboriginal boat peoples were at

the origins of Finnic languages. This lead me to explore

what happened to the boat peoples who remained in Europe, which to me

were clearly peoples known historically as "Veneti" "Venedi" or

"Eneti". That lead me to decipher ancient Venetic inscriptions in

northern Italy - but that takes me now beyond 2005 and into my most

recent period. Another diversion was in fiction writing. Going back

to childhood when I tried to creat comic strips, I had a talent for

creating stories, so around this time too, I tried to write a novel.

(see

Abbi) In any event,

these research.and creative

pursuits were for my own interest, and gave me no monetary rewards.

Artistically, this period 1995-2005 were mainly about making selling

small landcapes, and trying to find customers for the more expensive

art. All along, I did sell my prints casually when people showed

interest, even though I no longer aggressively marketed them.

GREEN

BORDER AROUND IMAGE MEANS THE

ORIGINAL OF THE PAINTING

IS STILL AVAILABLE- CONTACT ME.

A WHITE

BORDER

MEANS SOME LIMITED EDITION PRINTS OF

THE IMAGE ARE AVAILABLE TO PURCHASE.

3.1

FINDING THE TRADITIONAL SOLIDITY TOWARDS LANDSCAPES

In Central Canada there is plenty of wilderness ot

the northern boreal kind, wilderness whose wildness and

healthiness cannot be found anywhere else in the world, other than the

least inhabited parts of northern Europe and Asia. Thanks to the

Canadian artists of the early 1900's, the Group of Seven, who sketched

and painted the Canadian wilderness, Canada has a tradition in art that

captures the essence of the

Canadian wilderness It is not that the public every

consciously wanted a tradition of landscape painting that did so - it

came about as a result of the prior North American interest in the

wilderness experience.

In the early 1800's as European culture expanded

into North America, interest developed in the Native peoples there. In

the mid 1800's the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, created a poem

called "Hiawatha" which he based on legends and stories gathered by

Henry Schoolcraft, when he was among the Ojibwa in northern Lake

Michigan. By this time children were already making boys and arrows and

putting feathers in their hair as a result of the growing print media.

(Newspapers, then telegraphy, were spreading the news about the Native

"Indian" peoples), The poem "Hiawatha" and its author became extremely

popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Because of this popularity,along

with the development of railways, a tourist industry arose. Railway and

steamship companies began to promote tourist travel to various

locations from which they could experience the wilderness, complete

with "Indian" guides. One popular practice that city people sought, was

to be guided by an "Indian" guide to paddle canoes into Central

Ontario's lakes, to catch fish, and stop on a bank in midday to have a

"shore lunch" in which the Indian guide would fry up some fish they had

caught. They would then go back to the rustic lodge where they had

accomodation - unless they were adventurous and their Indian guide

guided them to camp through the night. Sportsmen of course were

adventurous, and went into the wilderness for many days and nights at a

time. In general, North America celebrated the wilderness. By the end

of the 1800's both Canada and America had created wilderness parks to

preserve the wilderenss and cater to this public interest in the

wilderenss experience.

Everyone who knows about the Canadian Group of

Seven, knows about their friend Tom Thomson (who died in a canoe

accident before the "Group of Seven" formed themselves). He hung out at

Ontario's Algonquin Park at a lodge there, and while he loved to take

excursions by canoe to fish etc, he also liked to capture his

experiences on small canvas panels. Note that at this time photography

was new - only huge cameras that took black and white - and recording

scenes in paint on small panels was the only way of capturing the

experience. That was the motive. Tom Thomson, or the other artists, who

formed a club to, together, go out into the wilderness and pursue this

practice of capturing what they saw on small panels. I believe that

when colour photography became simple in the last decades, especially

now with digital cameras, this motive of going on an adventure and

capturing it in images, would have been much less.

The point is that the "Group of Seven" began a

tradition of capturing the Canadian wild wilderness onto panels. As

they painted, they could do some organizing and design as required to

capture the feeling of a scene, but done in the outdoors, quickly, they

lacked the refinement of serious works of art. So the artists would

take some ideas from their small paintings, and develop them later in

the studio, resulting in the finished products that hang in art

galleries and art museums today.

The Art Establishment of the day turned up their

nose at the exhibitions by the "Group of Seven". By this time (around

1915 or so) the French impressionists were gaining popularity - those

were the Parisian artists who painted the scenery around the French

countryside with thick dabs of paint, to capture the feeling of the

scene. Everyone knows the name Van Gogh. He was one of the more

adventurous of them. The aritst of the "Group of Seven" did not imitate

the French impressionists, but simply wanted to capture the essence of

the Canadian wilderness - whatever artistic way that was achievable was

fair game: the ultimate purpose was to capture the scene in a way that

the viewer of it understood the subject matter, drawing from their own

experiences in the wilderness. These paintings were geared to

resonating with the North American wilderness experience that had begun

in the Victorian Age, and had resulted now in a wilderness tourism

industry with lodges, fish camps, canoe manufacturing, and wilderness

parks set aside by the governments.

The Art Establishment of Toronto - made up of men who

probably had never gone out into the wilderness - could not see the

relevance of depicting the wilderness in art. This was competely new.

The Art World of the time simply did not depict the raw wilderness.

Paintings should be of people, farm buildings, countrysides, vases of

flowers, gardens, streets, etc. Why would anyone want a painting of the

wilderness?!! The Art Establishment, being out of touch of the common

man who was now even going to their cottages in the wilderness in

summer, simply did not know what was happening, and that the general

public could relate to these paintings of the wilderness.

Art has always celebrated and reflected what the

general society was up to. But when elites develop to control the

valuing, production and selling of art, the general public changes and

values culture in their own unsophisticated ways.

Thus, to conclude, the 'Group of Seven' reflected

public trends towards the wilderness experience - first visiting lodges

and hiring "Indian" guides, and then actually getting their own

"cottages" and owning their own canoes and boats. Without knowing it,

when I grew up - my family going to the "cottage" beside the wilderness

every summer and even many weekends - I responded to the relevance of

painting the wilderness around me. And the proof of the relevance was

in my paintings of the scenery selling to other cottagers on my lake.

The capturing of the wilderness in art was not a formal new development

in the "Art World". It was simply a reflection of what the general

public was experiencing. When you experience the world in a particular

way, you want that experience to be captured and remembered.

And taking photographs was never enough.

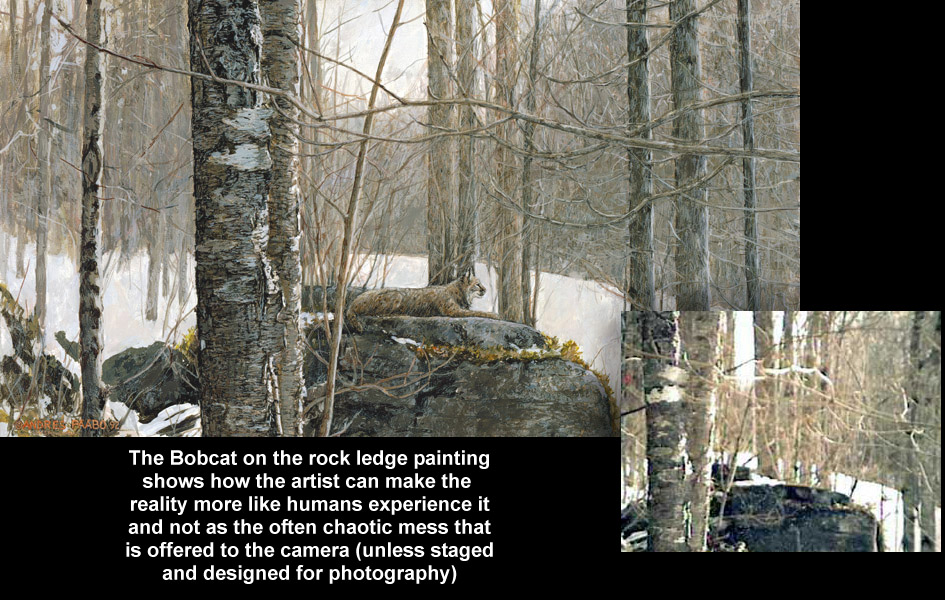

I recall many times a customer

giving me a photograph and asking me to make a painting of it. Why not

blow the painting up to a framable size? The answer is simple - the

camera sees everything coming in the lens, from the suble imbalances of

forms, the intrusiveness of random branches and leaves, unwanted logs

and such in the water, etc. You can see this for yourself if you

compare the actual scene as the camera saw it with the painting. That

having been said, one in a hundres photos of scenes, taken by a

photographer with a good eye for design, actually look good. But the

artist can take a scene recorded in a poor photo, one that most people

would consider terrible, and extract a moving painting out of it. And I

have many examples.

I therefore found myself painting the wilderness,

for exactly the same reason that the 'Group of Seven' did, to capture

the scenery that the public was experiencing, and to which they could

relate. While the people a century ago who could relate to the Group of

Seven painting from their summer vacations going to lodges, camping in

wilderness parks, etc, by the 1960's my similar small paintings were

images which resonated with people who went regularly to their summer

cottages. This landscape painting was valued and purchased, and still

is, since going to the cottage is a strong as ever.

By the time the 'wildlife art' phenomenon developed

there has been another new experience in the general public - the

naturalist experience. There was since I went to school in the 1950's

and 1960's much conversation about endangered species. There was also

discussion of how nature worked. We all became naturalists in our

childhood. We liked to see not just the landscapes with which we

were familiar, but also the animals in those landscapes. While at the

time of the "Group of Seven" people were focused on their experience

while canoeing, etc., by the 1960's, we were more educated about

nature, and adding animals to scenes was like the cherry on top of a

sundae. In my paintings when I joined this new trend with wildlife, I

would often hide the animal in the landscape, and the viewer would look

at the painting as they would naturally experience it while canoing or

hiking, and then suddenly they see the animal in the painting and shout

"I see the osprey!" in the same way that they would actually encounter

an animal in the real experience. I believe my paintings are all

fundamentally in the Canadian Wilderness Landscape tradition, and that

my adding animals to the scenes is purely an extension of that,

completing the scene with expected wildlife, mirroring the experience

of the person in that landscape suddenly seeing an animal.

While I do have a portrait painting background that

can lead me sometimes on a path of portraying an animal - as opposed to

showing them as part of a landscape - my paintings in general are

in the Canadian tradition of

mirroring the Canadian experience of the wilderness, including

animals that naturally are found therein.

Yes, I will explore and experiment in other

directions, but my art is rooted in the Canadian experience of the

Canadian wilderness based on my own experience.

When the "craze" with limited edition reproductions

faded away in the 1990's, I still had the landscapes. Although I could

not make much money spending weeks and months on my landscape paintings

because there was no marketplace of wealthy people available from me, I

could still make hundreds of small landscape paintings and do them

quickly enough that they had a market among all people who went to a

"cottage" in Ontario, or went "camping' in our wilderness parks.

(Art critics who dismiss landscape painting, and

realism, must stop to think of what art is - art is a mirroring of

society. In prehistoric times, people were interested in bringing down

big game so they put images of them on their cave walls. In ancient

Greece, society was immersed in Greek mythology, so they painted and

sculpted images from mythology. In Christian Europe everything was

about the Bible, so murals depicted scenes from the Bible. In the

Renaissance, there was a return to Greek mythological themes, including

scenes from the Odyssey. Today, the cottaging and camping

experience in Canada is not paralleled in most other parts of the

world, and therefore viewers of my art from elsewhere than Central

Canada might have some difficulty relating to some scenes, the

size of the world public that understands and relates to the northern

boreal wilderness is substantial. That having been said, an argument

can be made that truly universal art uses the universal imagery that

everyone understands - sun, sky, land, foliage, the general shape of

trees, grasses, rocks, mammals in general, the human form. . If art

wants to appeal to all of humanity, then it tries to restrict itself to

what ALL humankind understands, and reflect their experience. There has

been a trend in art to either become specific to a culture (such as

Andy Warhols making a big deal of consumer products like soup cans), or

become extremely universal - such as "abstract" art analogous to what a

chimpanzee, our closest species relative, will create when given some

paints and paper: it is an indulgence with doing things with paint to

experience the psychological reaction. I can certainly see there is a

relevance in artists creating paintings that have the same effect on

chimpanzees and apes as humans, then the art becomes very universal,

comprising not just humans but our species relatives!)

3.2

PORTRAITS OF NATURE: TECHNIQUE

In the period 1995-2005 I did not abandon my limited

edition prints - since most of them are very saleable: I simply have to

frame them and present them to the buying public. But I realized the

trend was over. It was no longer possible to hand 50% of the

retail price over the the retailer. It was only practical if I was the

retailer. I could then even give a small discount. Accordingly I have

not stopped advertising my prints online and inviting purchases via the

internet - shipped via the postal system.

But by 1995, my energy was put into the landscapes.

While the small landcapes were the "liquid" product, I tried to keep up

my serious landscape paintings - mainly to show what I could do if not

constrained by the need to make a living.

The following presents some of the serious larger

work, and further below, a large number of examples of my small

landscapes.

MY

TECHNIQUE IN THE SMALL LANDSCAPES AND SERIOUS LARGE LANDSCAPES IS THE

SAME

But first it is important for me to show that even

when my landscapes are very detailed, they are STILL quite expressive.

While I don't deviate unnaturally from nature's colours, textures,

shapes, what I do is paint in ways that mirror what I am

painting. When I paint water in a scene, I use a brush long

bristles and very fluid paint, often as if I am painting with water

colour. If I paint rocks, I may make the paint thick, and perhaps use a

dry-brush technique to reflect the character of the rock. Similarly I

get emotionally involved in the object I am painting, and that emotion

is captured in the technique. It is a new approach to impressionism.

The colours and shapes remain true, so it still looks realistic, but

the surface of the painting, even when the detail is high, is infused

with the emotion of the technique guided by my reactions to what I am

painting.

Furthermore, my serious large paintings start out

being similar to my small paintings, and then I simply use thinner and

thinner brushes, never losing the technique. From a distance and in

photos, the technique is not visible, but the real painting up close

has a similar feel as the smaller paintings where the technique is

obvious.

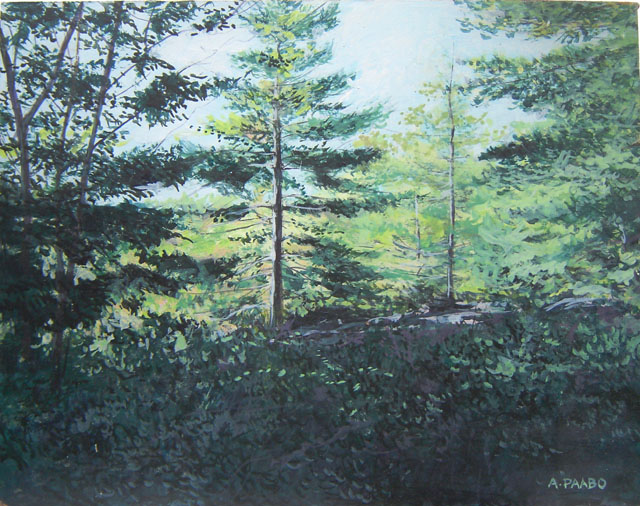

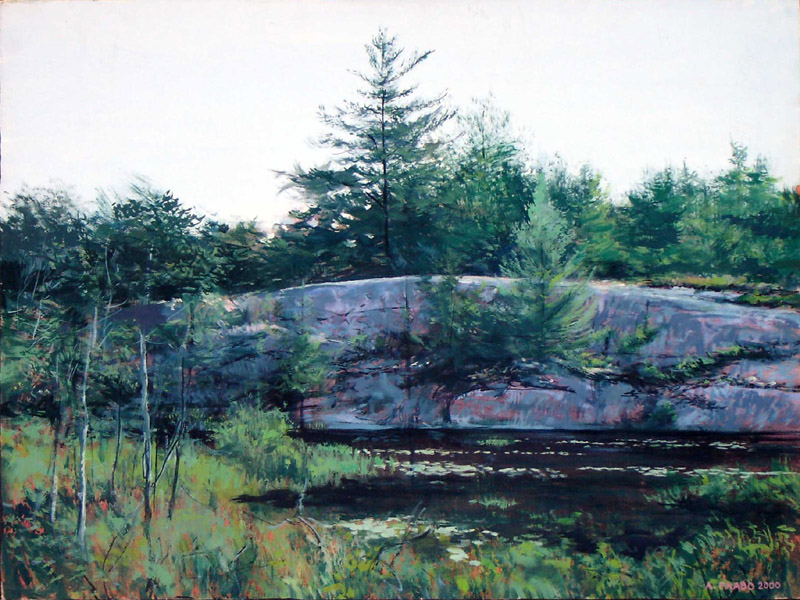

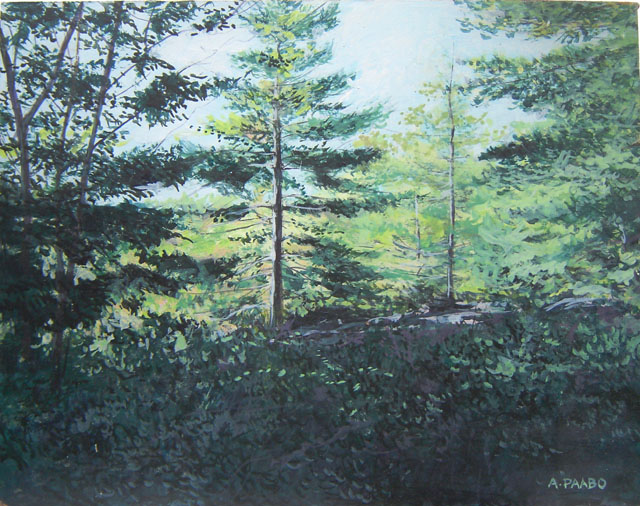

The following painting is a good example

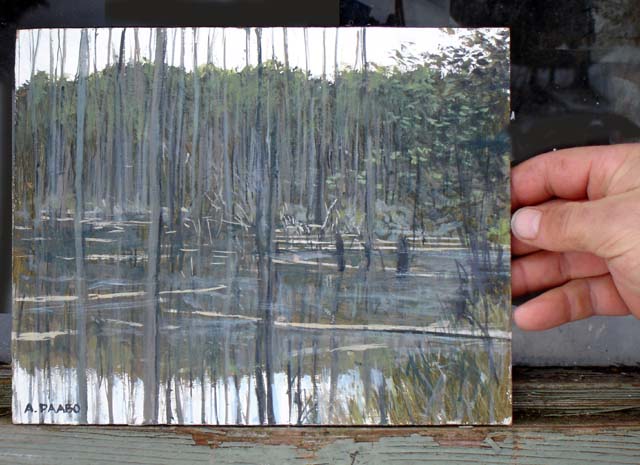

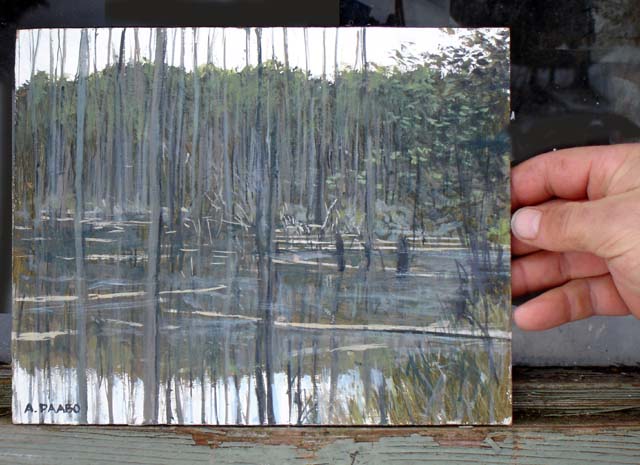

of my technique, here very visible on a small 8"x10" painting:

For

comparison, I show an example of an 8"x10" central portion of a large

48" x 36" painting.....

And yet, when photographed for this page,

you cannot see the nature of

the painting up close. That is why photos of my large paintings do not

do it the justice - the 'feeling' in the technique is lost in the long

distance view or photograph. (Painting

is Algonquin Pond #2 and is nearing completion and sale)

Therefore, do not be decieved when you see on these

pages photographs of large paintings that are in highly realistic

detail. If you see the actual painting, you will see that the technique

is the same as in the small paintings. The larger size simply covers

more canvas with the same technique. In real use of the large painting,

when on the wall, it is human nature to come quite close to it - say at

arm's length - since we are naturally drawn to detail. It is when one

gets close that the painting opens up and becomes quite

impressionistic

THE

ALGONQUIN POND SERIES

HOW

THE CREATION OF A LARGE PAINTING IS THE SAME AS FOR A SMALL PAINTING AS

WELL - ONLY THE BRUSHES BECOMES FINER AND FINER.

The following is the first painting called Algonquin

Pond. It so happened that I decided to record the entire process of

creating it. As you will see, first photos of the real place are a

little chaotic and off balance, but I can use it as a beginning point.

Then you will see that unlike many illustrative artist who develop the

painting, pencil it out, in advance, and then use the same small brush

throughout like a paint-by-number, I begin with a large brush, looking

for the design, trying to make the painting appear in my mind's eye in

advance. This is also the approach used by Robert Bateman. I believe

our methods are the same because we both began our art career trying to

emulate the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson with a technique that

"bang", started painting the scene right off without any finicky

predesign.

ORIGINAL FIRST SMALL PAINTINGS

ORIGINAL FIRST SMALL PAINTINGS

Two

small 8"x10" paintings of the

Algonquin Pond location. They became the jumping off point for the more

serious larger paintings below. I refer to these as well as photos of

the location that I originally took. My intention is to create a large

30"x20" painting but with the same level of detail - which results in

up close there being much more work in the foliage, grasses etc, where

in the small original much of it is blurry.

The painting begins by roughing it in using reddish colours that are

opposite to the greens that go on top.In the next period of work I am

adding greens and rough forms. It

is very loose and rough up close.

You

can see that I am beginning to develop the trees in the backgound to

give me more clarity as to how the background will look.

I now give attention to the

foreground pond with lilypads- lots of dots! The next period of

working on it, I do not like the trees in the background and blur them

for now. I work more detail into the background. Note I work no more

than 2-3 hours at a time, as the brain gets tired.

When

I return to work on the painting

I tackle the background trees in

the hill again and am more satisfied. I now have a good idea of where I

am headed. And then begins the many days and hours of making all the

elements in the painting very detailed, because it is designed so that

the viewer can study it quite close.

THE FINAL PAINTING

ALGONQUN POND 30"x20"

This

painting too is also a portrait of a location, because it describes the

location in detail. A portrait describes a specific subject but as in

human portraiture someone who does not know the subject matter, can

still relate to it.

MORE

PAINTINGS BASED ON THE SAME LOCATION

I continued to explore the subject, with two other paintings based on

the same location which I call Algonquin Pond #2 and #3.

ALGONGUIN POND #2 48"x36"

Note

that this

painting is different from the original "Algonquin Pond" shown above.

But since the painting portrays the same location, if you did not

compare the two, you would think they are the same painting. But they

are just two paintings that happen to portray the same location.

ALGONQUIN POND #3 48"x36"

This

version of Algonquin Pond is based on the region to the right (south),

and here I explored oil painting and impressionistic techniques

Note how this painting captures more of the "feeling" of a scene, while

#1 and #2 are more descriptive.

VARIATIONS

IN TECHNIQUE, SIZE, MEDIUM AND SURFACE

These three paintings are of the same location. Note how each

time I elect to use different techniques. Note too that I am not

committed to all details, but allow myself to change things in order to

arrive at a good design and impression.

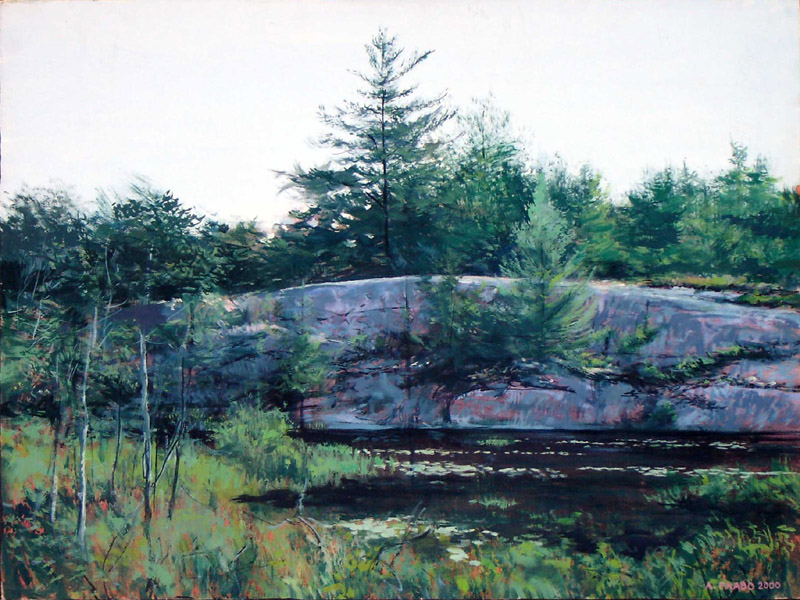

ROCK RIDGE - THE FIRST AND SECOND INTERPRETATIONS OF THE

LOCATION

These

paintings of generally the same location and subject,. began with the

small 8x10 painting to the left above, and later I created a larger

more organized version in 16x20 on the left. These lead to a rather

large painting on canvas shown below

ROCK RIDGE, LARGE VERSION ON CANVAS 36"x24"

This

is not a "final version" because the two earlier ones are not intended

to progress towards this one. Rather all three are different approaches

to the same subject matter. What happens is that I find a location so

interesting that I need to explore it in further paintings.

EXAMPLE:

MY ART STRIVES TO SHOW WHAT THE HUMAN MIND PERCIEVES, NOT HOW THE

CAMERA SEES

The human mind

does not observe the

reality in the same way that a machine (ie a camera does). A camera

records everything that comes in the lens. That image does also come

through the lens of the eye and falls on the retina, but it is when

that image reaches the brain, that the brain filters, or sifts, the

image, to screen out what is intrusive and/or undesirable. The best

example would be a scene of a lake through a thicket of branches. Take

a photo of this scene, and you will see all the chaos of the branches

in the foreground. But that is not what you, the human remember about

the scene. The human mind will filter out the intrusive branches in the

foreground and see that nice scene in the distance. The human mind will

also overlook things being out of balance, even in the desirable part

in the distance. The artist in fact portrays the scene as the human

mind actually sees it, not in the imperfect way the lens of the camera

saw it. That is why photographs will never replace well-done art,

except where the photographer consciously captures just those scenes

that by chance happen to already be perfect. A wildlife photographer

typically has to take 1000 photos of an animal before by chance he

getsclear: both;

a shot that is perfectly designed. (The artist can take imperfect

photos and MAKE the perfect image from the imperfect source photos!) It

is also the reason for studio photography - the subject can be fully

arranged and lighted to be perfect for the camera.

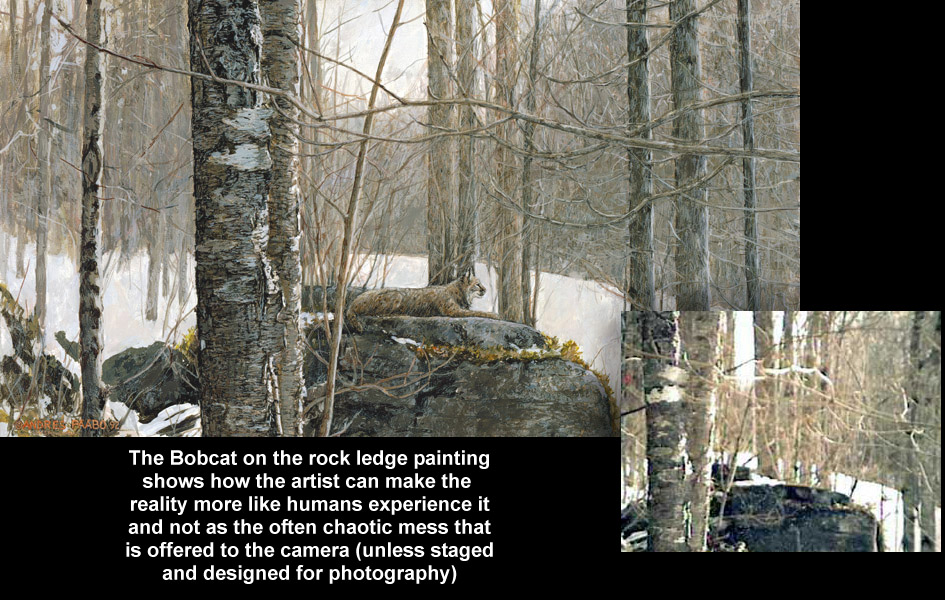

The following painting is a vey good example of how

I greatly I can

improve on what is really there, what the camera sees, making the scene

look more like the human mind sees with its filtering and balancing.

ROCK LEDGE WITH BOBCAT - AND A CAMERA VIEW OF THE ACTUAL

PAINTING.

Compare

the painting with the photograph to see what I have done - made the

trees more vertical, stretched the scene sideways for a more aesthetic

rectangle, made the branches follow simpler design - note how the

foreground branches are waves working together and integrating into the

abstract design. The original scene is full of chaotic randomness but

my mind's eye can see how, like a gardener, I can subtly rearrange

nature to look simpler, more powerful, and with a stronger abstract

design.

3.3

A SELECTION OF PORTRAITS OF NATURE (LARGER THAN 8" x 10")

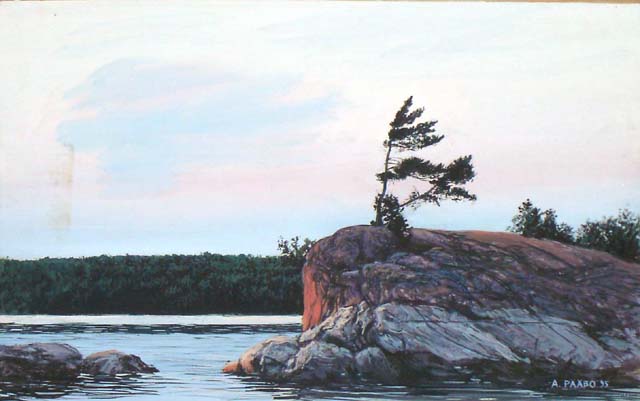

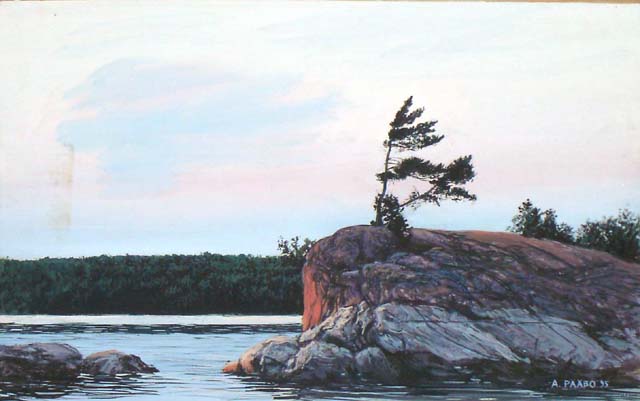

PICNIC ISLAND about 24" x 16"

'This

island is a central focus on Eels Lake, and called "Picnic Island". I

caught this amazing lighting in the later afternoon.

PINK ROCK 20"x16"

I

was attracted to this scene in a nearby marsh and this tries to capture

the feeling and the abstract design

MORNING SUN 16" x 14"

I

encountered this scene one early morning at Bon Echo Provincial Park

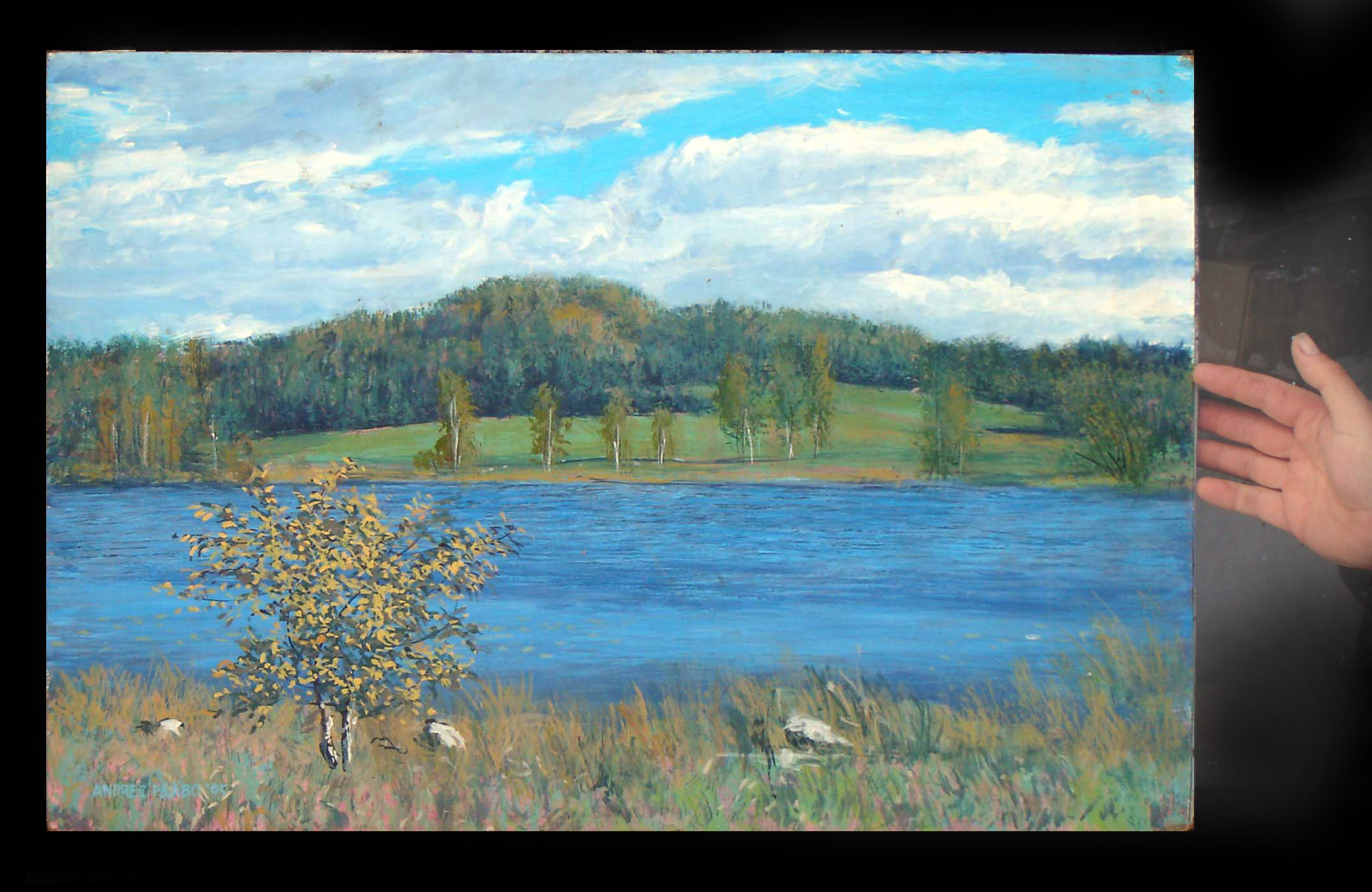

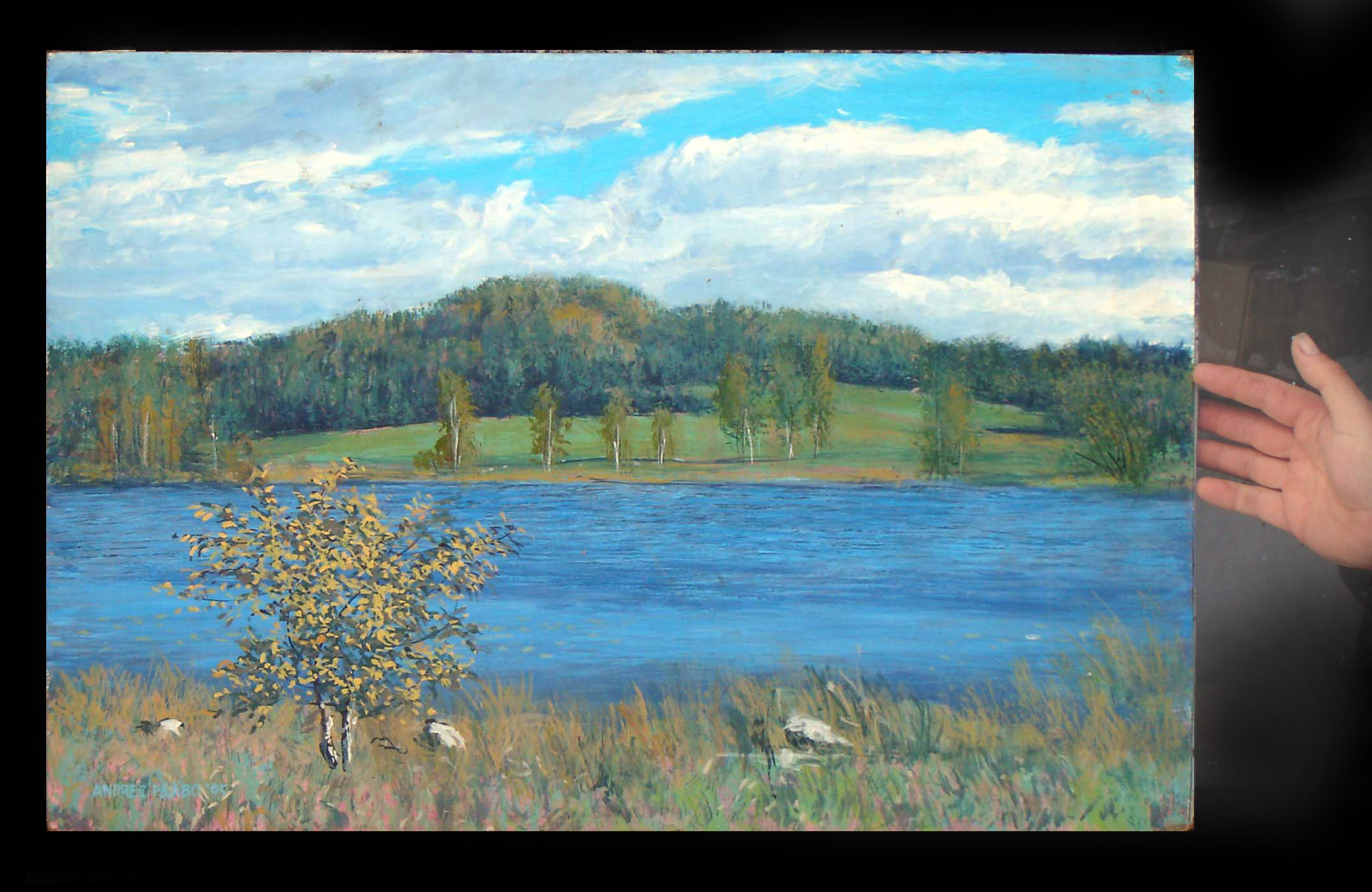

BLUE LAKE

This

is an instance in which I painted with a thick brush on a large panel

in the same way I paint with a small brush on a 10"x8" panel. Since

price is based on time taken, this only enlarges the art, but does not

add to time. But the disadvantage was that most people did not have the

wall space for a large painting, and always chose the smaller version.

PICNIC ISLAND IN WINTER 30" x 20"

This

island in Eels Lake is very photogenic. Its windswept trees and granite

rocks are very attractive. This became my norm for larger paintings -

to paint with the same detail as my small 8x10's

This

shows the same island as above, but in a quiet fall afternoon. (The

water level is lowered in fall, revealing ore of the pink granite rock.)

LATE WINTER RIVER 30" x 20"

This

painting was actually based on a scene I saw near Thunder Bay. It's

beauty lies in the way the eye can meander into the distance.

EAST SHORE 30"x20"

I

was attracted to this shore scene not far from where I am located

because of the attractive pines. I added the kingfisher in the

foreground as a surprise element - however it has a significant role in

creating interest in the foreground.

WINDSWEPT CLIFF

I

painted this scene several times, based on a cliff at a nearby lake. It

was an interesting pursuit of textures and shapes. Each time I tried to

improve the design and effect.

LAZY RIVER 24" x 24"

I

painted this on canvas in a traditional 'painterly' style mainly to

remind myself of the traditional technique which I learned as a

teenager.. Although it is quite large, it's price is not high because

it is done in a loose style.

Pink

rocks covered with pines and junipers etc is common across northern

Ontario, In this case I made the distant shore thin, very far, in order

to keep attention on the foreground. As with the above painting, it is

painted large and not in the normal detail level

AUTUMN HAZE

This

painting is mostly subtle colours intended to capture the feeling of a

hot fall day - Indian Summer.

MARSH ALONG LAKE ONTARIO

I

found this scene located along Lake Ontario near Brighton as

having an interesting design of colours

RAIN CLOUDS about 24" x 16"(?)

This

scene scene in southern Ontario farmland, become a narrative painting

by the presence of the farmhouse.

SOME

INSPIRED PAINTING PROJECTS

When more information and detail is introduced into

a painting - also

of larger size - the painting becomes more storytelling, has more

narrative - and that additional content takes the painting to a new

level.

THE TEACHING ROCKS 48" x 32"

THE TEACHING ROCKS 48" x 32"

This

painting, more than any other wildlife painting, is also a portrait of

a real place. The rock carvings in the image are accurately positions

and painted. While it portrays a specific place, someone who does not

know that can see it in general terms as 'Native rock carvings'

This

painting, more than any other wildlife painting, is also a portrait of

a real place. The rock carvings in the image are accurately positions

and painted. While it portrays a specific place, someone who does not

know that can see it in general terms as 'Native rock carvings'

(RIGHT: HOW THE PAINTING LOOKED AT EARLY STAGES

>>>

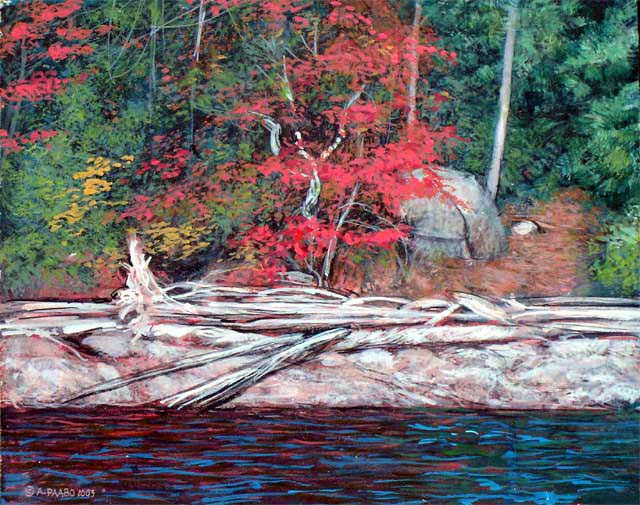

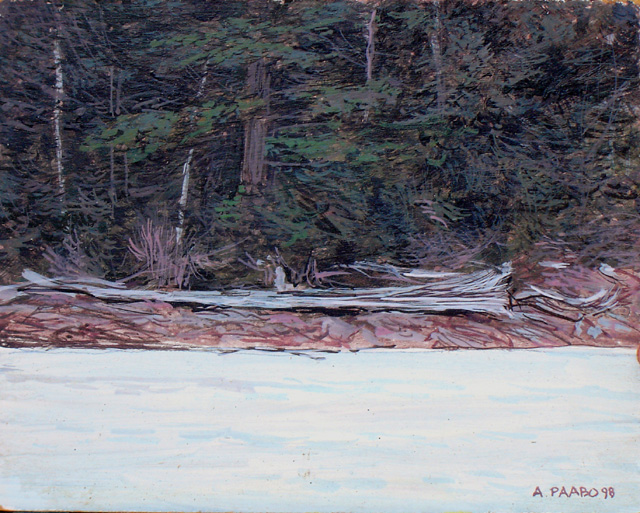

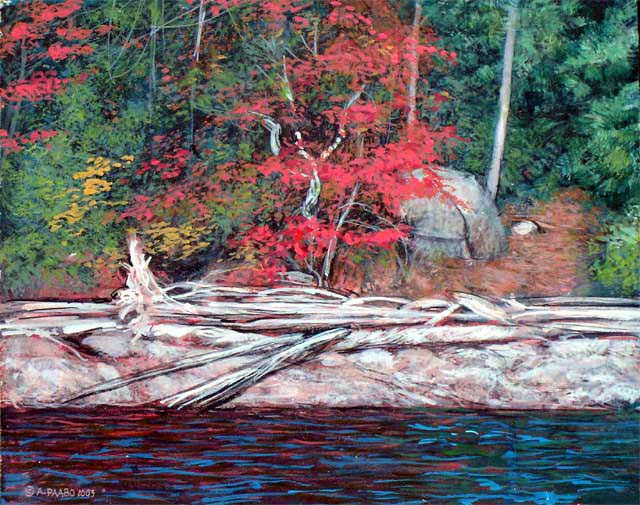

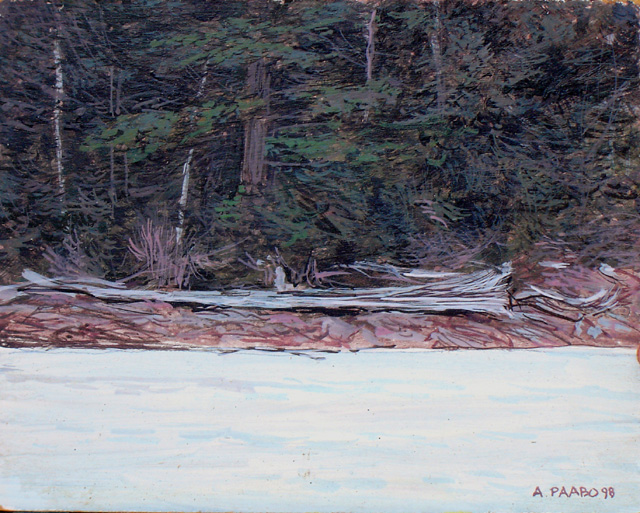

DRIFTWOOD SHORE 48" x 32"

DRIFTWOOD SHORE 48" x 32"

The above painting

is also more a

description of an actual place, but it anyone can relate to it, because

its elements can be found everywhere - sunlight, driftwood,

rocks.

LILYPADS

ABOUT 30" x 20"

I

was fascinated how a lilypads formed an interesting pattern that even

if you do not know what the reality is, produces an interesting

abstract pattern with the white flower as the focal point. And when you

know what is being shown, symbolism and metaphor enters the art.

LILYPADS

ABOUT 30" x 20"

I

was fascinated how a lilypads formed an interesting pattern that even

if you do not know what the reality is, produces an interesting

abstract pattern with the white flower as the focal point. And when you

know what is being shown, symbolism and metaphor enters the art.

EDGE OF THE EARTH 48" x 36"

Based on flat rock edge on the east

coast of the Bruce Peninsula facing Lake Huron, I saw the abstract and

symbolic design in in, contrasting rock with water with sky. The figure

at the edge gives a human context to it. It is also part of my

exploration of adding humans, instead of wildlife, into landscapes (see

later for more about my putting humans in landscapes)

EDGE OF THE EARTH 48" x 36"

Based on flat rock edge on the east

coast of the Bruce Peninsula facing Lake Huron, I saw the abstract and

symbolic design in in, contrasting rock with water with sky. The figure

at the edge gives a human context to it. It is also part of my

exploration of adding humans, instead of wildlife, into landscapes (see

later for more about my putting humans in landscapes)

HERON ROOKERY 30"x20"

This painting originated from a

photograph, but I was already familiar with such scenes. I adjusted the

scene to make it more balanced, and more interesting - the usual

technique.

HERON ROOKERY 30"x20"

This painting originated from a

photograph, but I was already familiar with such scenes. I adjusted the

scene to make it more balanced, and more interesting - the usual

technique.

Many of the paintings shown on these pages

actually portray a real place in the background, and the animal has

been worked into the scene. Thus to one degree or another all

portrayals of nature are portrayals of real things the artist sees.

Nature scenes cease to be portraits, if the artist revises, changes,

modifies the scene which was the original inspiration. Some of my

paintings are like that for the simple reason that nature is not

perfect. If you saw the actual photo of a particular scene in a

painting, you will see that the photo is quite chaotic and unpleasant.

I have redesigned nature to make it more 'perfect'. It would be

analogous to painting a portrait of a person, and making that person

look more beautiful that they really are.

3.4 WILD STILL LIFES AND CLOSUPS

When one thinks of landscape, one things of scenes

receding into the

distance However, just as in the traditional art there are closups of

bowls of fruit or vases of flowers, etc, so too it is possible for a

painting to study an interesting section of nature up close. Here are

some which are clearly that.

FALL SPRING 20" x 20"

While I start with a real scene, in

order to create an organized, interesting, system of shapes, textures

and colours, I have to slightly 'redesign' nature to remove the

imbalance, etc. This image could not be achieved with a photograph -

well, maybe if you spent a week and took 1000's of photos you may find

one that is perfect - or the photographer carefully set it up in studio.

FALL SPRING 20" x 20"

While I start with a real scene, in

order to create an organized, interesting, system of shapes, textures

and colours, I have to slightly 'redesign' nature to remove the

imbalance, etc. This image could not be achieved with a photograph -

well, maybe if you spent a week and took 1000's of photos you may find

one that is perfect - or the photographer carefully set it up in studio.

DECORATED ROCK 20" x 28"(?)

I saw these interesting autumn

colours at a rock beside the road, and used it as a jumping off point

for a painting. Note, as always, I basically redesign the actual nature

to make all its elements form into a moving abstract design. As I say

again and again, nature is never perfect. The artist has to rearrange

things, add and subtract, etc. (Or a photographer has to spend a summer

taking thousands of photos to find a perfect design occuring naturally

- all MY photos are imperfect, and my job is to make them perfect.)

DECORATED ROCK 20" x 28"(?)

I saw these interesting autumn

colours at a rock beside the road, and used it as a jumping off point

for a painting. Note, as always, I basically redesign the actual nature

to make all its elements form into a moving abstract design. As I say

again and again, nature is never perfect. The artist has to rearrange

things, add and subtract, etc. (Or a photographer has to spend a summer

taking thousands of photos to find a perfect design occuring naturally

- all MY photos are imperfect, and my job is to make them perfect.)

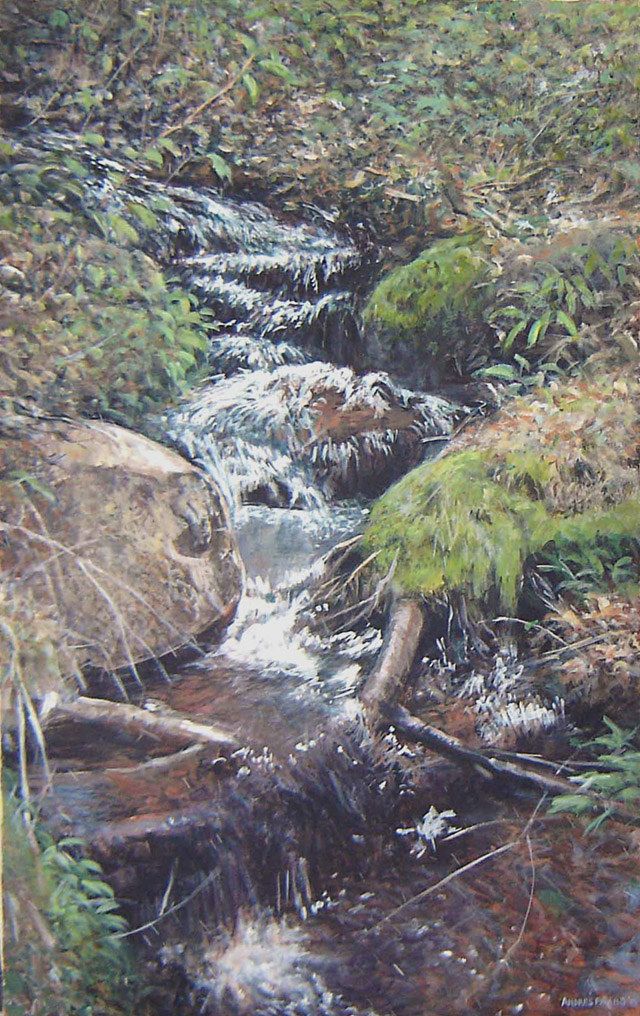

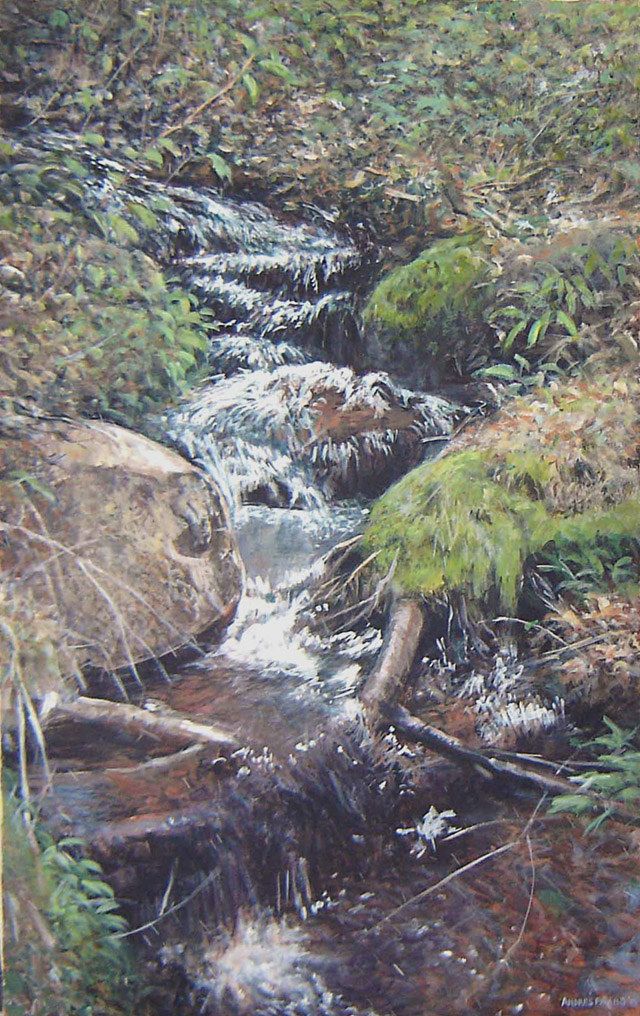

SPRING RUNOFF 24" x 42"

I painted the action in the lower

portion years ago, but I also had photo records of the upper portion.

So I had the idea of creating a long painting showing more of the small

stream . In this case, there is more from my imagination. It is also a

looser painting.

SPRING RUNOFF 24" x 42"

I painted the action in the lower

portion years ago, but I also had photo records of the upper portion.

So I had the idea of creating a long painting showing more of the small

stream . In this case, there is more from my imagination. It is also a

looser painting.

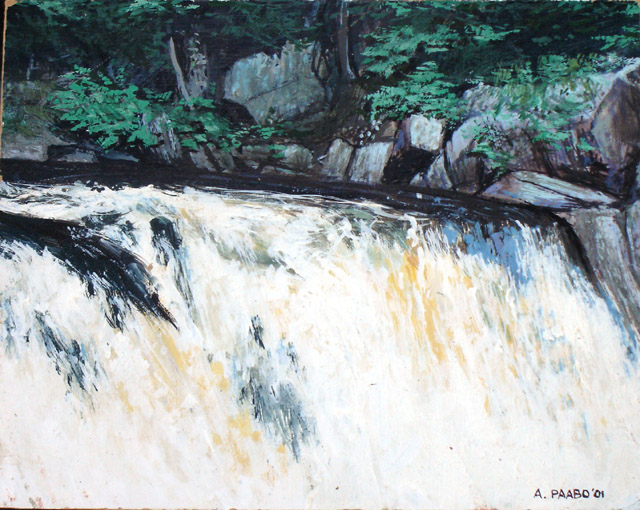

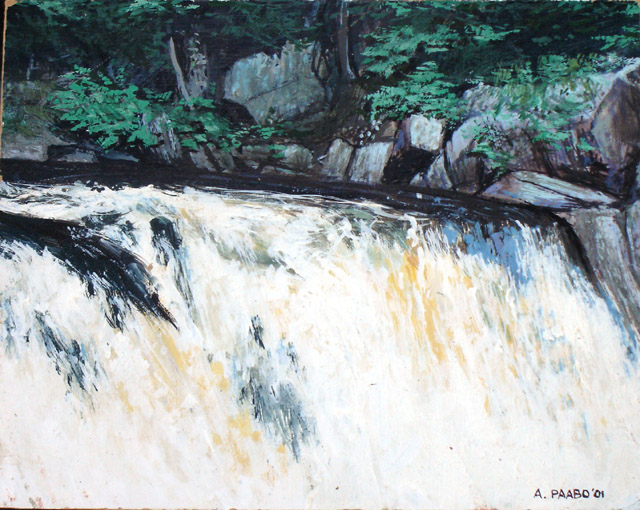

RAPIDS 20"x12" (?)

This painting was a challenge to

myself to see how real I could make moving water during spring melt,

inspired by the rapids of Clanricarde Creek.

RAPIDS 20"x12" (?)

This painting was a challenge to

myself to see how real I could make moving water during spring melt,

inspired by the rapids of Clanricarde Creek.

SPRING RUSH

This scene occurs in early spring

when suddenly the weather is very warm and snow is turning into streams

everywhere, and then in some weeks it is gone. This is a case of me

trying to capture not just the warmth but also the lively action

SPRING RUSH

This scene occurs in early spring

when suddenly the weather is very warm and snow is turning into streams

everywhere, and then in some weeks it is gone. This is a case of me

trying to capture not just the warmth but also the lively action

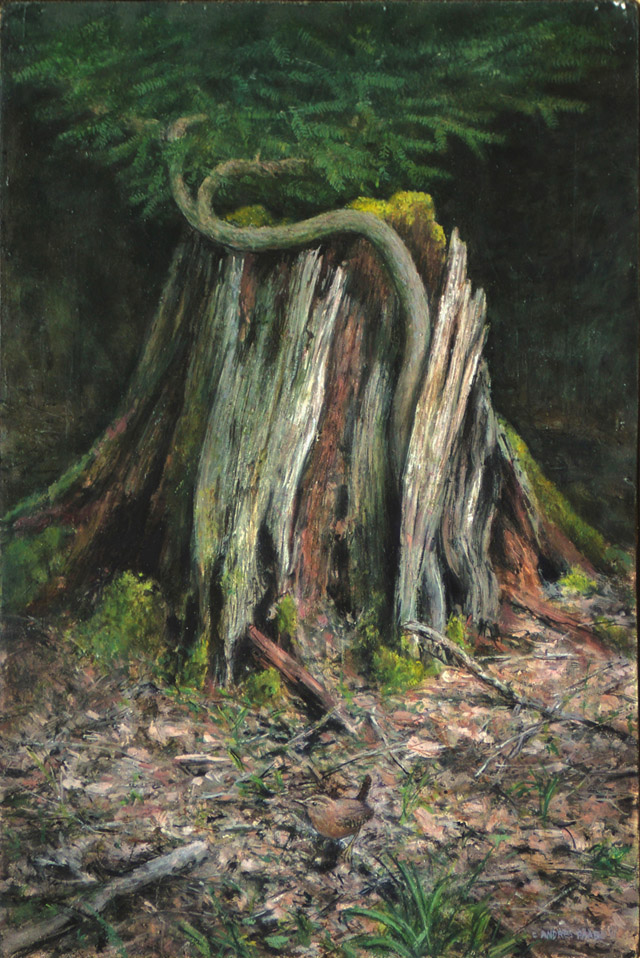

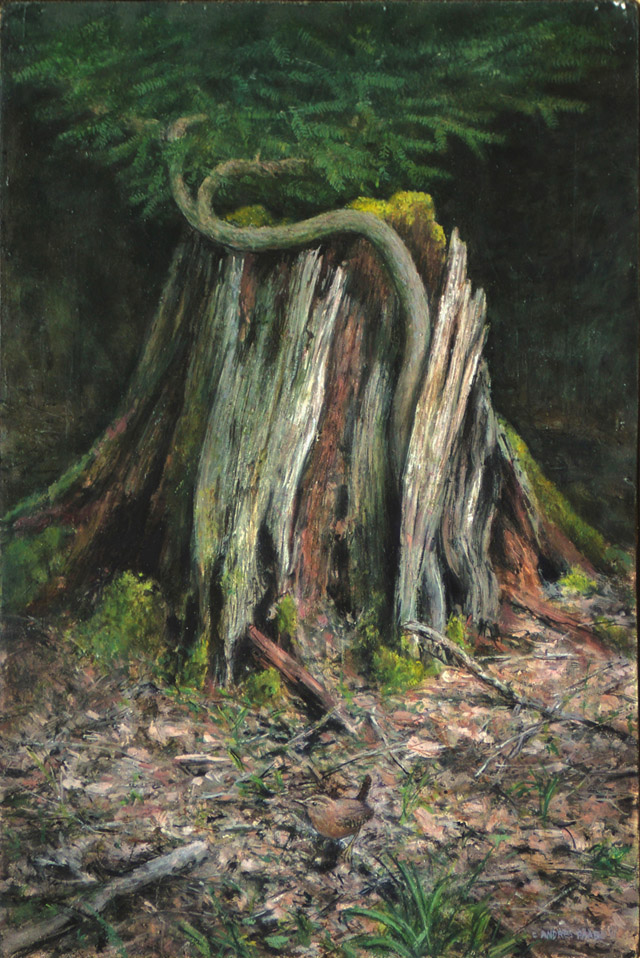

REBIRTH

This is a painting unlike anything

you have seen before. It shows how a new tree can grow out of a

decaying stump. This gave my a symbolic idea - showing how nature

regenerates itself, recycles itself, whereas pollution does not

recycle. As a final touch, if you view the original, you

will see a wren on the forest floor.

REBIRTH

This is a painting unlike anything

you have seen before. It shows how a new tree can grow out of a

decaying stump. This gave my a symbolic idea - showing how nature

regenerates itself, recycles itself, whereas pollution does not

recycle. As a final touch, if you view the original, you

will see a wren on the forest floor.

3.5

NATURE AS ABSTRACTS

I have two large 48"x48" paintings which, altough depicting

nature,

highlight the abstract side of the painting. Some people seeing them

for the first time do not realize immediately that it depicts a real

natural scene.

PATCH OF ICE 48"x48"

I was intrigued by the 'feeling' of

the trees in a bay - subtle greys. To enhance it I imagined a

pack of wolves there. To give a strong sense of the third dimension, I

wanted some detail in the foreground, and decided on showing a region

of the ice that was blown clean of snow by the wind. Overall, you will

note that this is an abstract design as well.

PATCH OF ICE 48"x48"

I was intrigued by the 'feeling' of

the trees in a bay - subtle greys. To enhance it I imagined a

pack of wolves there. To give a strong sense of the third dimension, I

wanted some detail in the foreground, and decided on showing a region

of the ice that was blown clean of snow by the wind. Overall, you will

note that this is an abstract design as well.

TEMAGAMI SUNRISE 48"x48"

I

saw such a misty scene when I travelled south from Temagami,. Ontario,

at about 6AM. I stopped and took many photos, and those became my

source of inspiration to develop a painting that portrayed a real

event, but also, overall had the same effect as an abstract.

A BASIC TRUTH: ABSTRACT ART IS

UNDERNEATH ALL GOOD ART BUT AVERAGE

PEOPLE NEED REALITY ON

TOP, AND CANNOT UNDERSTAND IF REALITY IS MISSING.

|

This may make you ask the question whether this

validates "abstract art". The answer is that ALL good art has a

good abstract design underneath it. Abstract art is about the

psychology of shapes, colours, lines, textures etc. But this psychology

has developed in humans through a million years of experience in

nature. Thus abstract design is born of our experience in nature, and

so by using natural elements to create good abstract designs that

create particular emotional and intellectual responses, we return to

the very origins of abstract art. All humans will understand abstract

art if it is created from real natural elements, because the realism

puts the viewer into the context. When abstract art is removed from any

reality, then the average person has no way of interpreting it.

Sometimes abstract art attempts to help the viewer by the title - such

as calling alot of vertical black lines as "a forest". Without

the realism on top of abstract art, it is merely a meaningless bunch of

lines, shapes, colours, etc. and no different from what can be produced

by a child or a chimpanzee simply playing around with artist supplies

to achieve "interesting effects". Perhaps there is a place for

"interesting effects" but they should be priced accordingly. When the

Art Establishment is confronted with art produced by apes or

chimpanzees, they say "it is not art because the ape or chimp does not

intentionally design the painting. Instead, the ape or chimpanzee

generates them one after the other and it is the human art dealer who

selects the ones that look interesting." My response is that human

artists do the same!! They generate painting after painting, and then

select the ones that 'work' and hide or paint over the ones they

reject. The only difference is that while the chimpanzee has not

context by which to select the best, the human artist does. But when

either man or ape creates interesting lines, shapes, colours etc, they

are both doing the same thing - achieving results that resonate with

psychology, which originates from evolutionary experience in nature. If

a chimpanzee artist learned what kind of art his human master likes, he

too can select which of his wild explorations to show to his human

master. In my opinion, EVERY painting I create is an abstract. The fact

that I make the abstract coincide with real elements from nature, does

not alter this fact. The only difference is that the human being

can understand it when the abstract has reality on top of it, as it

gives a real world context, while if it doesn't it is just a jumble of

lines, shapes, colours, etc in limbo, without any connection to reality

- except if it is used for giving interesting design to walls,

furniture, carpets, etc.

I selected the two large paintings as the best

examples of simple abstracts, but ALL paintings have abstract designs

underneath them. The trick is to use the abstract design to generate

the psychological responses suitable for the subject matter. (For

example, one would not want to have bright, happy colours if the

painting shows a pack of wolves. ) As you saw in my demonstration

above, all my paintings are abstract paintings within a couple hours.

Developing the painting to put the realism on top, complete with

additional symbolism and narrative, can take another hundred hours.

Thus it is outrageous that art dealers will try to sell abstracts that

take a half day to create for the same price as a realistic painting

that took further weeks.

3.6 MORE IMPRESSIONISTIC TREATMENTS

The truth is that there is a spectrum of techniques

that range from pure non-representational abstract (lots of lines,

shapes, etc) that produce emotional reaction) to suggested reality in

the abstracts (such as an artist creating alot of vertical lines and

calling it a 'forest') to more and more reality, leading to the

impressionistic techniques. When the abstract designs are noticable in

the painting technique, we call the work "painterly". As I have said

elsewhere, traditonal realism strives to make the painting technique

invisible. It is similar to how handwriting is invisible - the reader

seeks what the handwriting says, But if the writer writes with crazy

flair, the handwriting begins to intrude. Note that it is not necessay

to be realistic for the painting technique to be invisible- if the

viewer is familiar with the technique and is looking beyond the

technique in the same way we look past the handwriting to its message.

If the abstract design, thus, is not noticable, and

the purpose of the painting is to offer a visual narrative, then that

form of art will be the other end of the spectrum. But there is always

the abstract design underneath all art, whether or not we notice the

handwriting, or painterliness, or not.

The following are examples in which I leave some

presence of the painting technique, where this helps convey emotion.

(Detail has the problem of making a scene cold and technical, so

sometimes blurring, etc to avoid obsessing on detail is desirable)

THE FENCE AND FIELD

The

background is blurred and suggested, partly to keep the viewer's

attention on the foreground.

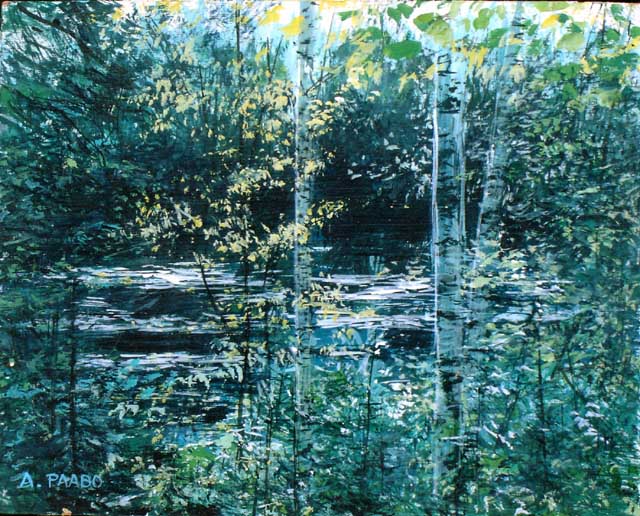

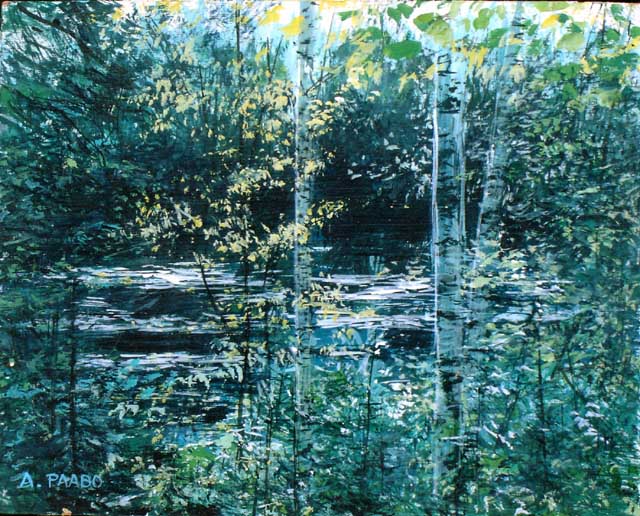

THROUGH THE TREES

This

scene had a great mess of foreground trees, so I decide to blur it and

show it impressionistically so that the foreground would not be made

more important than the pond we are actually looking at

OPPOSITE SHORE

This

is the scene on the opposite shore from me. It is the same location as

the painting of the deer when I was 14 or so

THE POND

All

my paintings start more or less like this, but this is an established

painting style for final works - most commonly used by illustrators.

Usually I consider this stage to be the beginning of a painting I

develop into more detail. However, this one happened to be very lively

and interesting at this stage, and I realized I might leave this

painting as is If I want to paint this scene in more detail I can

start another painting. It is easy to see that it could also be a

detailed scene perhaps containing a heron in the water - or a

moose. An artist has to know where to stop.

The above examples merely show my flair and emotion

in my brush technique found in all my paintings, taken to extreme.

These are only some examples where the technique is especially

noticable.

3.6

PORTRAITS OF NATURE: SMALL LANDSCAPES

I have already spoken in detail about the small

paintings by which I first capture the images of nature I encounter.

This section will present many of these small paintings. Many were sold

in galleries for prices up to $500 framed. It depends on the success of

the result and the level of detail. When I was a teenager in 1964, I

remember selling a small painting for as little as $95; but if we

investigate inflation since then, that price would be as much as $500

today. As money loses its value, people remember how much things cost

earlier. The pressure was on me to keep selling my small paintings as

if in 1960-70 Canadian money. I had a major row with someone who wanted

to commission a portrait from me, and pay about the same as his

grandfather paid back in 1964 which was I believe $65. That one had two

hour sittings five times, totalling 10 hours, or $6.50 per hour. Even a

teenager cleaning floors in a fast food joint will make twice that

amount. In reality, adding preparations before and after, the proper

amount of time would be more like 15 hours and if I demand a more

reasonable $35 hr, then that gives roughly the $500 that inflation

suggests. So I insisted it had to be $500. Nothing irritates me more

than the lack of respect for original painting and customers trying to

make me accept less than minimum wage for my lifetime of experience and

talent. I got so fed up by the person who wanted a portrait of himself

for the same as his grandfather spent 50 years ago, that I was prepared

to let that commission pass by. It took him a year or so before he

contacted me again. What an insult! I should be making $50 per hour. In

Toronto there is a portrait artist whose head-and-shoulders painting

starts at $1000. That is very reasonable, and only possibly because he

deals directly with the public and does not have a gallery commission

subtracted.

So the following paintings took - all time

considered - about one per day. What is a day of work worth? Minimum

wage is $100/day. To make a living I allowed art dealers to buy small

paintings for that, in effect treating me like a minimum wage earner. I

later raised it to $200, which was better. The dealer puts a frame

around it and sells it for $500-$600. You can see who gets paid and who

gets screwed. If you are interested in art, do not buy from art

dealers, especially since now you can contact the artist directly,

visit them to see the art, and study their art on the internet. It all

goes to show that there are three types of people in the economy -

those who make things, those who buy things, and the middleman or

middlewoman who tries to screw both.

You can see why I hate marketing my art. Let me

create art and recieve buyers directly and then I am happy. We live in

a new world today where this is becoming the case - where the middleman

or middlewoman is increasingly

unnecessary. If a painting on this website has a green border, you can

contact me directly, negotiate, and obtain the painting - especially

now that shipping has become very streamlines and sophisticated with

the development of internet shopping.

EXAMPLES OF THE

SCALE OF THE SMALL PAINTINGS IN FRAMES

Here

are two small paintings that I framed and put on my wall because of the

success in my technique.

What

you will notice about the following small 8"x10" paintings, is that I

will paint anything that appeals to me. Not everyone cares for

everything I paint, but the constant truth is that if I am personally

excited about the subject then that excitement will enter the painting,

and the viewer will feel it. In addition, I actually enjoy the

experience. Everybody wins.

Thus

anything that interests me is valid to paint. It also allows me to get

ideas that will lead to major paintings. It also constantly trains me

to adjust my subject matter to produce strong underlying abstract

designs that make the painting rise above the mundaneness and chaos of

the real wilderness.

The

rule in all art - paint, write, etc what you know - also applies. If

you know subject matter better than the common average person, then you

can show things that the average person does not know. All viewers want

to gain something from a cultural experience. If you merely repeat what

they already know, you are boring.

I

travel through nature and then see

something that strikes me as interesting. I stop and wonder what it is

that is captivating me, and then I can explore making the painting

capture that special thing that captivates me. If successful, I

transfer the special thing to the viewer.

In

some places in my area, the wilderness has grown on the remains of

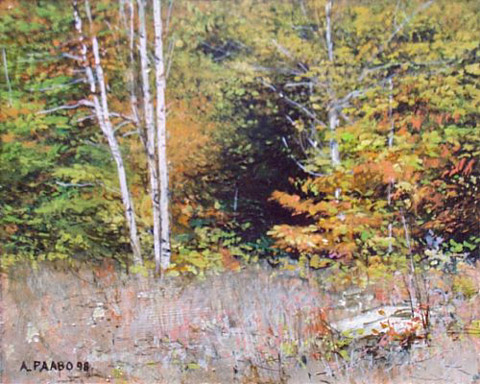

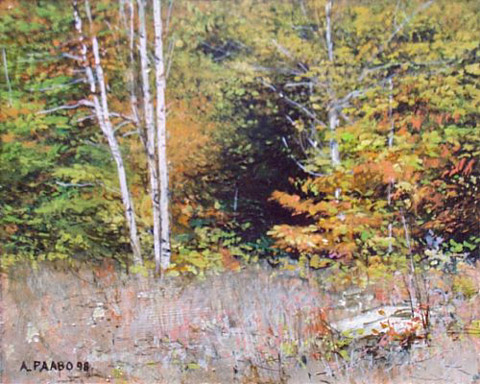

clearing and farming a century ago. This two paintings are such areas -

where there are grassy clearing or meadows.

What becomes subject matter for my paintings is often totally

unexpected. I simply see something interesting that can be captured in

a painting. Sometimes the attraction is the play of light on water,

sometimes it is the abstract shapes in the remains of a past fire, that

I can arrange into an abstract design.

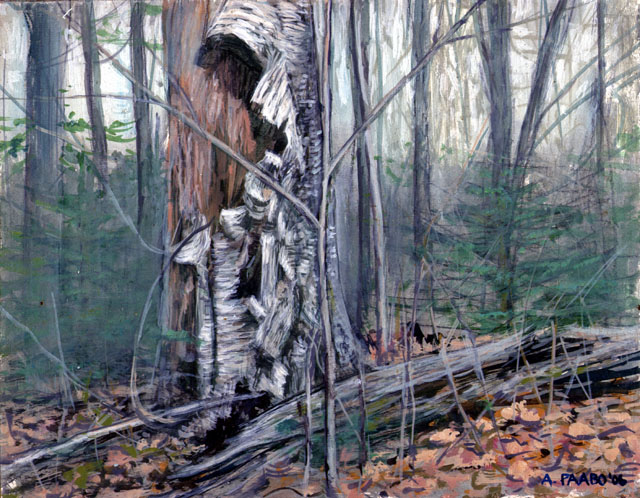

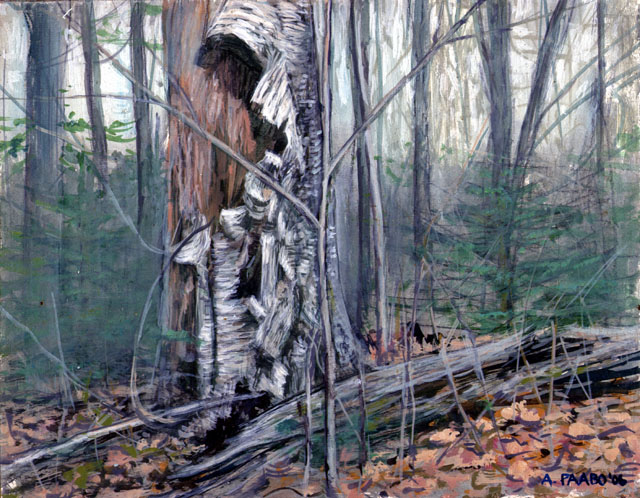

The

above two paintings are of the most unlikely subject matter. They are

studies of things in the forest that we normally would not expect has

any beauty, but I then see the beauty and extract it. In the painting

on the left, I was attracted to the misty feeling of the scene. In the

right, I was fascinated by the interesting textures of the broken

birchbark.

In

these examples, I became fascinated by the character of birch trees in

one and driftwood in the other. What happens is that I in effect give

these object livingness. In a way you could say that in giving life and

importance to things in a landscape, I am expressing the original

animistic view of nature found in all humankind who lived or still live

integrated with nature.

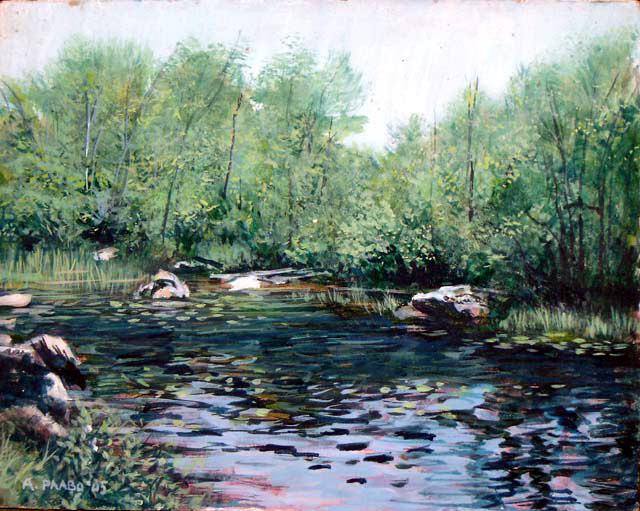

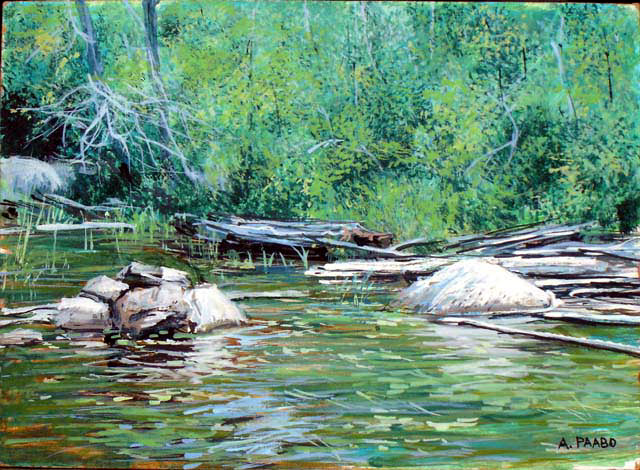

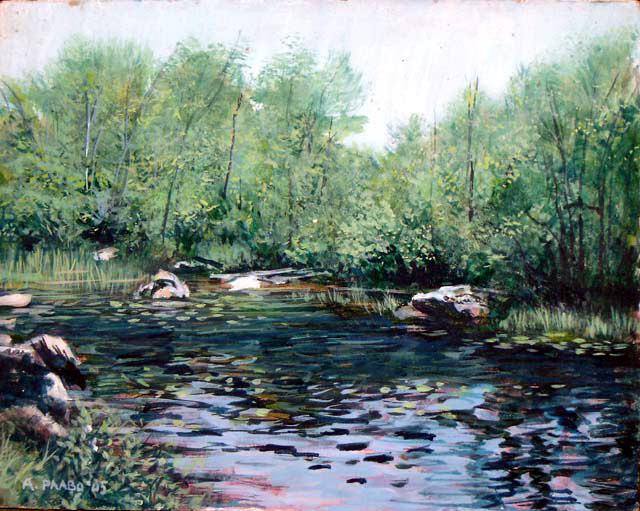

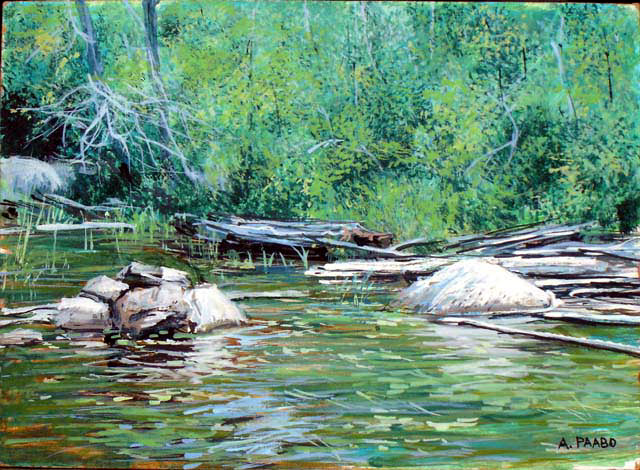

These

two are studies of light and water. Sometimes what I find fascinating

is unique to me. As much as I like the painting on the left, not many

people can see it on their wall.

These

two paintings are of the same pond-like area beside the highway near

Buckhorn Ontario. I cannot understand exactly what appealed to

me about it. Perhaps it is the variety of detail, and the strong

colours reflected in the water.

Two

paintings inspired by rapids or falls. In one case I wanted to see if I

could paint the falls in such a lively way that it looks real. (Bad

painting fails to make water feel fluid). The other painting shows

rapidly moving water in advance of rapids and falls, but it is made

more interesting by the variety of elements in it and colours.

Both

these paintings lacked variety of objects, but in one, I worked at

capturing the character in the trees, and in the other capturing the

liveliness of sunlight making leaves sparkle

90% of my small quick paintings is of

the wilderness in my environment no more than maybe 4 km away.. But now

and then I go to other places, and see something interesting. The

painting on the left is a design I saw at Sandbanks Provincial Park in

the afteroon sun. The painting on the right is of the ridges west of

Burleigh Falls.

But

most paintings are from not far away. One only has to keep one's eyes

and mind open for the ideas to appear unexpectedly. The painting on the

left is in the bay just a km to the south, and the painting on the

right is a rocky cliff I saw from my boat a km or two to the north on

the lake.

These

two paintings feature roads. The road on the left is Eels Lake Road.

The painting on the right simply shows some trees etc to the left of a

narrow dirt road that used to lead to my property. I think the painting

on the right is a remarkable capturing of the scene

Winter

does not reduce the opportunity for attractive subject matter. The

painting on the left is interesting from its great variety of elements,

including grasses. The painting on the right is a little n the simple

side. I thought that adding an animal, like a wolf or bobcat,

might add more subject matter, but I left it as is.

An

interesting scene can appear anywhere. The left scene is late afternoon

at the snowcovered pond made by beavers, and the right scene is the

play of sunlight on leaves and branches at a clearing. Both paintings

use the device of having a way for the eye to recede into the distance.

The

scene with sunrays falling on an island is something I saw. I am

inspired to possible develop a large painting with such a sky effect.

The other painting, the old burnt stumps was a natural subject for

study.

Two

scenes involving water, captured while I was travelling.

The

paining with the maple leaves is somewhat designed to form an abstract

arrangement. The sunset scene attempts to capture an unusually golden

situation on the water.

AND THERE WERE MANY MORE...

It is clear that painting these small

paintings was

invaluable to me for exercise, for getting ideas for more serious

paintings, and for making a living - since people loved most of them

and because they took less than a day each to paint, they were

affordable. There was a time between 1995 and 2005 when I had

maybe as many as a hundred of them that I took around to galleries. It

was exhausting, and I needed to take breaks, and work on more serious

paintings too - such as those shown ealier on this page.

written

April 2016

by the artist

contact: A.Paabo, Box 478,

Apsley, Ont., Canada

2016 (c) A. P��bo.

This

painting, more than any other wildlife painting, is also a portrait of

a real place. The rock carvings in the image are accurately positions

and painted. While it portrays a specific place, someone who does not

know that can see it in general terms as 'Native rock carvings'

This

painting, more than any other wildlife painting, is also a portrait of

a real place. The rock carvings in the image are accurately positions

and painted. While it portrays a specific place, someone who does not

know that can see it in general terms as 'Native rock carvings'

LILYPADS

ABOUT 30" x 20"

I

was fascinated how a lilypads formed an interesting pattern that even

if you do not know what the reality is, produces an interesting

abstract pattern with the white flower as the focal point. And when you

know what is being shown, symbolism and metaphor enters the art.

LILYPADS

ABOUT 30" x 20"

I

was fascinated how a lilypads formed an interesting pattern that even

if you do not know what the reality is, produces an interesting

abstract pattern with the white flower as the focal point. And when you

know what is being shown, symbolism and metaphor enters the art.