Human nature alone

will not produce organized trading activity on the large scale. Human

nature alone will not cause humankind to be completely immobile -

tied to the same general location in a settlement generation after

generation. The circumstances of North America some centuries ago,

before colonization from Europe, were essentially what happens when

there is not large scale trading activity. Without peoples accustomed

to boat use, tribes will only interract with immediate neighbouring

peoples. Interractions with distant tribes do not happen, and awareness

of what exists further away is vague.

This is how it was in Europe before the development

of large trade systems. The Europe seen by the Romans was much like

that original North America - tribes were not aware of what was further

away, there were hundreds of languages and dialects and cultures.

Anthropologists a century ago know the nature of natural human

organization. National Geographic magazine was filled with strange

tribes in remote jungles in strange places. In North America around the

17th century, French explorers describe great variation from tribe to

tribe. For example, one tribe might have no restrictions on

complete nakedness, with the next was very strict. South American

jungles still had peculiar customs by the 19th century. Peoples who

stretched their lips and inserted discs of wood. There was body

tatooing, peculiar puberty rituals. Aztecs sacrificed maidens at the

top of pyramids. All this variety and peculiarity arises naturally from

lack of large scale organization. Today our entire humankind is united

by world-wide mass media. The whole world has the same large scale

cultural behaviour. Perhaps in a century from now we will look back and

think of some of what we consider normal today to be bizarre.

BEFORE TRADE SYSTEMS AND BEFORE POLITICAL ORGANIZATION HUMAN SOCIETIES WERE NATURALLY LOCAL

Pseudo-scholars today, who promote the idea that

there existed large scale nations existed in Europe before the Roman

Empire. The Roman Empire appears to have been the first truly large

scale organization of a large empire. You may say, what about ancient

Greece? If you read literature from ancient Greek, you discover that

there was no large scale government, and that Greek was a trade

language that also developed into a common language for other purposes

like culture. (Think of English today). There were city states who were

essentially tribes living in organized settlements. The ancient

historian Herodotus described all the tribes who came together to wage

war with the Persians in the 5th century BC, and his writing shows just

how different the participants were in terms of customs, appearance,

language, beliefs. When Romans developed the Roman Empire their system

promoted Roman nationalism. Everyone was encouraged to think of

themselves as Romans, wear togas, etc. Today we are used to this,

because all our nations are politically organized around large

scale nationalism. The largest European nation today is larger than the

largest natural tribe.

The notion that there could have been an empire in

Europe, or anywhere, before the Roman Empire, is ridiculous. When we

think of Indo-European cultures, whose language speaks of origins in

farming and herding, we have to think of hundreds of dialects. Without

large scale governments, it would be impossible for there to be one

language across central Europe. There was never a single large scale

Celtic nation. There as never a large scale Germanic nation. There was

never a large scale Slavic nation. The variation of languages and

cultures was as strong as Herodotus described in the tribes who came

together for the Persian war. Or imagine North America before

Europeans landed on its shores.

But why do scholars and pseudo-scholars imagine that

there existed a single Celtic Europe, a single Germanic Europe, or

single Slavic Europe before the Roman Empire? It is because larger

political units only developed since the Roman Empire, and copying of

the Roman heirarchical system.

In natural human organization, a tribe consisted of

a number of extended families associating with each other. Basically

the natural number of families is about 4-8. Each extended family

has a chief, and the grand chief of the entire tribe is formed from one

of them, and the family chiefs form a council to deal with tribal

issues.

When it gets larger, especially when the total

number of individuals exceeds about 60, men who challenge the chief can

break away and take a few families with them, and form another tribe.

The new tribe of course has to move far enough away so as not to remain

on the territory of the parent tribe. It is just like when a young

person leaves home - he or she wants to move far enough away to break

with their parent family.

But evironmental pressured may make it desirable

there is no breakaway, but the tribe tried to accomodate more families

and keep internal peace. This is achieved if the council of family

chiefs becomes more organized, and adds rules and punishments. When it

gets of substantial size, there is a king, and police to ensure this

oversize tribe holds together. Thus ancient kingdoms can become quite

large if well organized and regulated. But ultimately the "Kingdom" was

still a tribe.

BEFORE THE ROMAN EMPIRE: NO LARGE SCALE POLITICAL NATIONS

History shows that before and after the Roman

Empire, there were strong kingdoms with significant armies to keep the

ruled peoples in line, but these kindgoms could only extend their rule

as far as it took to send their army from the central palace location

to the most distant point the king claimed as his. How far is that?

A larger political unit could be obtained if several

kingdoms formed a confederation with a common purpose like defeating an

enemy. But confederations were usually short term.

The Roman Empire took another approach. It created a

multi-leveled government ruled from Rome. Armies were stationed all

over the map ready to head out to any location of unrest. It helped

that it sought to be democratic - that means it was not possible for

any one person to become a permanent ruler and command an army to keep

him in power. Indeed the natural government of humankind was

democratic. The chief of a tribe was chosen from among the chiefs/heads

of participating families. While there were traditions of certain

families inheriting the right to rule a tribe, it was just a default

suggestion, since families with traditions in leadership, would tend to

inherit the skills.

The Roman system, thus was able to create a very

large political unity by a heirachy of officials looking back to Rome,

along with military camps everywhere. In addition - and this is

important - Romans built long overland roads everywhere, so that an

army or officials could reach any location overland in a week or so.

Before the Roman Empire, roads were relatively local

and not very good. They were used only for regional marketing. A

cluster of settlements would establish a market town and cut roads by

which the settlements could get their produce to market. The condition

of the roads were only as good as the locals were willing to keep them

in shape. Romans created long roads on the large scale and

intentionally made them to last forever. Today sections of 2000 year

old Roman roads can still be found.

But before Roman roads created long distance

overland travel - assuming you had horses and chariots - the only

long distance highways were made of water, and travelled by boats.

Archeology in North America has determined that

North America had some long distance trade, originally oriented

north-south via the Mississippi. Apparently copper from north of Lake

Superior, for example, found its way to the Gulf of Mexico. This could

reflect what was found in Europe before the Bronze Age. Major long

rivers that linked distant locations were clearly used for carrying

wares long distances.

But long distance trade could only develop where

settled peoples developed an interest in places and goods further way

that what they knew in their local cluster of settlements. Today

there is world-wide shipping and there is very little left that we

would consider exotic - unless it is rocks from the moon. But earlier,

all local products would be ordinary and boring and we would be

fascinated by something new and different from far away.

But boats and rivers also had an intermediate role

as well. Even using a local river to go to a market located

strategically along a river, to which surrounding settlements could

bring wares to market without needing to deal with troublesome roads.

Thus the development of boats had a major impact to

all levels of trade everywhere there were waterways. Methods of

manufacturing with wicker or boards provided ideas for creating boats

sufficient for carring wares to market.

We can conclude that before the Roman Empire, there

were actually very few roads in general. Roads were trails created

naturally from being trampled.

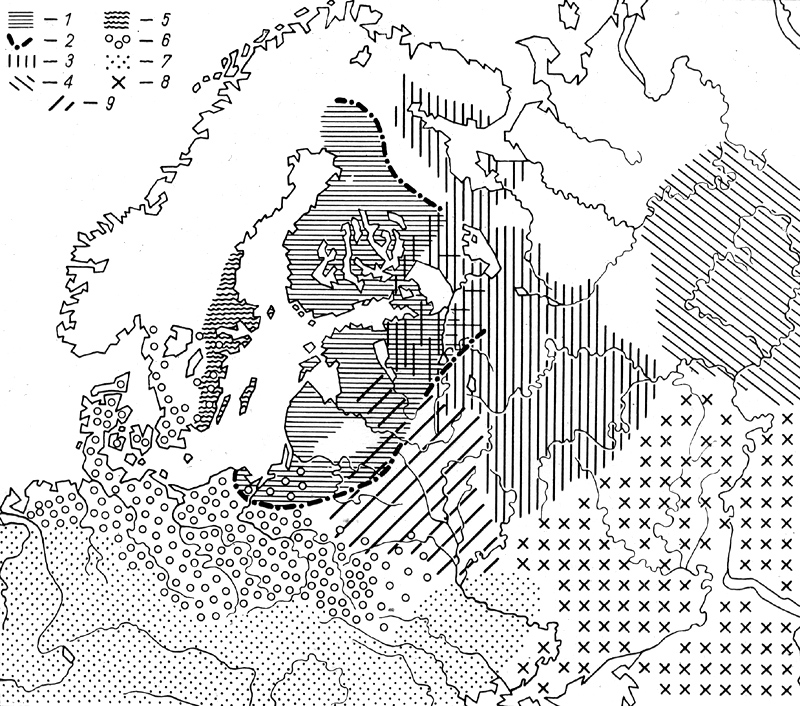

TRADE SYSTEMS ORIGINALLY PARALLELED WATER SYSTEMS

The natural system of water drainage in Europe

became the heirarchy of shipping. Ancient peoples even understood it.

Tributaries of rivers sent waters down to points where several

tributaries met. Replace the word 'water' with 'goods' and it is easy

to see that different levels of market towns reflected the structure of

the water system. The dominant market would be the one at the mouth of

the river that also recieved ships via the sea.

The whole economic system based on using boats in

water systems to carry wares, was made possible by the adoption of

boats. Farming peoples could easily adopt boats for local travel, but

large scale trade tended to remain in the hands of the peoples who

originated the boat and the use of them in trade.Accordingly we should

discover in Roman era toponymy, that place name involved most in long

distance trade have descriptive names when interpreted with FInnic.

Between the major long distance routes and the local water routes to

local markets there were varying degrees of influence from the long

distance traders, according to the degree the participants needed to

master the large scale trade language.

Let us consider Gaul in Roman times

In his military campaigns to conquer Gaul, Julius Caesar saw three

distinct geographical areas with the same language, laws and

institutions -

Aquitani, Belgae,

Celtae. The actual division

into districts when Roman Gaul was formed, proved that these peoples were

defined by the the Garonne, Rhine, and Loire water basins. This

indicates that all peoples were using boats to travel up and down the

rivers in order to visit various local markets and the major

port-market at the mouth of the river.

Based on my theory that large scale traders

originated millenia previously and established a large scale Finnic

trade language, I studied place names around Roman Gaul and Britain, to

detect Finnic names - using the criteria that ancient peoples named

places by describing them (plus an added ending to signify it was a

name and not just a description - usually a genitive)

As much as I wanted to be able to translate with

Finnic (using Estonian) place names everywhere in Gaul, but in fact

most of the believable translations were at the trade routes by which

ancient traders crossed between the Mediterranean and Atlantic via to

rivers at the neck of the Iberian Peninsula - Ebro to the south of the

Pyrennes Mountains, and the Garonne to the north,

The most notable place name, still found on maps

today is the Spanish name for the Bay of Biscay - Mar Cantabrico. There

is also a mountain range Cordillera Cntbrica. Roman texts also identify

a tribe of that name south of the region of Bilbao or San Sebastian.

The word resonates with Estonian

kandav riigi

'nations that carry, transport'. The Ebro flows towards the

Mediterranean from across the mountains Thus, there were people

with the role of carrying wares between the Atlantic and the upper

Ebro. The word "Ebro" itself combines two quite common word elements in

place names in western Europe - most noticable in Roman times - an ABA

which was the word used for a river that descended to the sea, and was

therefore a very long estuary, and the element RA (RO, RU, etc) which

was used often as a suffix meaning 'way, route' (In modern Estonian it

appears in

rada, rata 'path, way' and is also at the origins of English

road.) It appears at the origins of the names of all major trade rivers - Rhine (Roman

Rhennus), Rhone (Roman

Rhodanus) and the -RA element occurred as a suffix in many river names - for examplem Loire was Roman

Liger or

Ligera, Oder was

Otra, the Danube was to Greeks

Ister or

Istra, the Dneiper was

Nistra, the Volga according to Ptolemy was

Rha. All these names interpret well - for example LIgera resonates with Est

liige ra(da)

'moving-way'. Later in history the element TURU was used to identify a

market, and it combined TU with the RA (RU, RO) and it meant literally

'bring-way' (the place to bring wares). At the same time,

the TU element (or TO, TE, TA, etc - in FInnish today

tuo, Estonian

too) was used to name rivers too. For example what Greeks knew as

Istra was also known by Romans

Danubius (read Est TOON 'of bringing' ABA 'estuary')

Near the mouth of the Ebro today, there is the

coastal port of Tarragona. Perhaps like Ebro, this is a word that has

resisted becoming distorted in the last couple millenia, since I can

see in it the Estonian

turu-konna 'community of the market'

After a while the language of trade rivers becomes

clear. Some elements resonate with Basque. Basque may been the language

spoken by the

Cantabrico tribes, the tribes who were involved with the international trade.

To the north of the Pyrennes is

the Garonne. This river drains the other way. Thus a shipper could use

the Garonne when travelling with the flow from the Mediterranean to the

Atlantic an use the Ebro when going the other way. If one had a barge

and did not want to row against the flow. One would begin the journey

from Narbonne (I believe known as

Narbo in

Roman times) Narbo is the same word as today Narva in northeast

Estonia. It occurs in other locations like Narvik Norway. It exists in

many locations in ancient texts, and the stem is NER or NAR. It refers

to a location of a water route, in which the boat is forced through a

bottleneck, a narrows. It is origin of the English

narrow, and the name

Norway.

The latter comes from the narrow passage for travelling between the

North Sea and the Baltic. It originally applied to that area, but was

extended up the coast in the first millenium as the Danes conquered the

coasts that became Norway. (We note too that the district in northern

Spain where trade crossed from the Atlantic to the Ebro, is today

called Navarra.) Some may ask 'how do you know the word has Finnic

origin?' It is also used to name the kidney, by which fluid is

eliminated. (Estonian

neer)

The name of the Garonne River in Roman times was

something like Garumna. The GARU element appears frequently in

Ptolemy's Britain (

Albion) in early Roman times, and its context of use seems to resonate most with Estonian

korja meaning 'gather'. The English

carry

probably is related. The river name probably originally meant '(river)

of the 'gathering land' or 'carrying land' implying that shippers

dropped their wares there in warehouses, to be transferred to

ships. An ocean-going ship of course did not travel through the

rivers. So unless a ship went to the Mediterranean via the Strait of

Gibraltar, the wares it carried were transferred between associated

shippers based on either side of the Iberian Peninsula. In any event

goods were funnelled from

Narbo to the Garonne, and travelled down the river to the mouth, where, according to Caesar the port town was called

Burdigala (or similar), today Bordeaux. The word Burdigala resonates with Estonian

purde küla

meaning community built on piers. The mouth of major

rivers is always a swampy delta, so it is easy to imagine a port built

on piers located up the Garonne estuary as far as a ship could go

without going aground.

All the names easily translatable with Estonian into

meaningful descriptions are ones that can be easily associated with

major long distance trade. The descriptive words, furthermore, can be

found all over Europe!!

The names that change least are ones that are little

used and taken for granted. The neck of the Iberian Peninsula has a

mountain range called Pyrenes, which resonates with Estonian

piirine 'of the nature of a boundary'

THE SETTLED FARMING PEOPLES TAKE OVER THE MAPS

It is easy to see how rapidly a farming-based

civilization can come to dominate a map with names, by simply looking

at a North American map and realize just how many settlements were

created only in several centuries.

In Europe too, farming was successful It allows

humans to survive on small plots of land, whereas aboriginals in the

wild had to procure food over large wilderness territories.

Farming was successful and farming settlements

multiplied. The new settlements will be named in the farming peoples'

language. It reminds me of how the North American map is filled with

towns and cities with original new names, but major geographical names

still have their original pre-colonization, Native names. (Like for

example "Mississippi" is Algonquian for 'river') Modern maps have so

much new naming that it is difficult to find surviving early names of

origins in the original boat peoples who established trade routes as

early as 5,000 years ago, and even names in Roman times had so much

development that in Roman times too, place and tribe names were

dominated by new names.

Celtic scholars will claim that these place names I

attribute to a large international trade language of Finnic origins,

are all Celtic. But that is like claiming all names in the modern North

American map are European. Scholarly opiniom lacks nuance.

I have given examples around the neck of the Iberian Peninsula,

but I could also continue and also look at other locations. Everywhere

there is evidence of an early large scale language. And the

languages of settled people adopted many of the commonly used words.

The word "Don" for trade rivers, is found from the Black Sea to Spain

to Britain. Why is this word so popular? Because it meant 'bring'

(probably developing the added meaning of 'carry'.

One finds the same words everywhere. Since this is a

subject that can take up a thousand pages, I will focus on the ancient

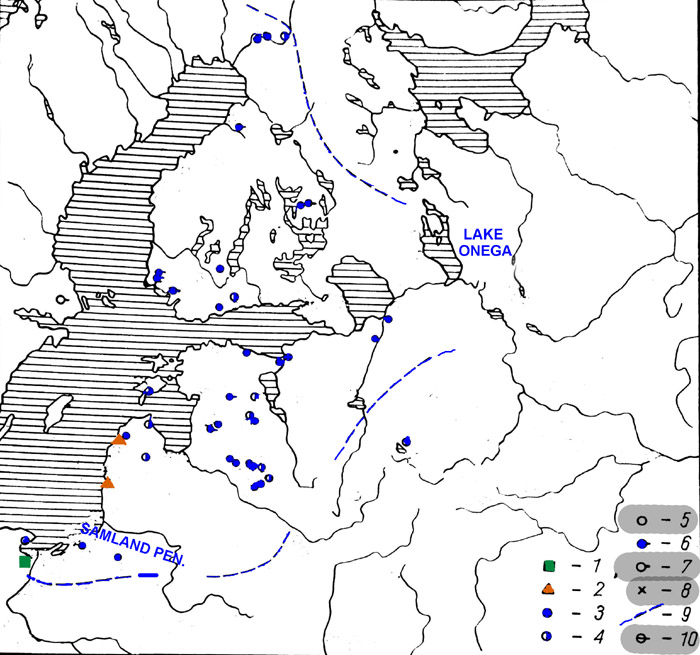

Greek world. The steady Baltic amber trade that began 5,000 years

ago, as findings of Baltic amber in Babylonian tombs, must have

left a strong mark on the ancient world. And that is the case.

The Development of Professional Trade

INTRODUCTION

Archeology

has found evidence dating back to the Stone Age, of goods originating

in a location appearing in another location far away. Humans are

natural towards sharing, and when two groups met, there is an

obligation to share what each has in excess. If the excess is in

natural resources, then they are happy to give away some of it. When

there is plenty there is low value. Elsewhere where people lack that

item, obtaining it has great value. Thus sharing excesses makes

everyone happy. If one group takes something from another that not in

excess, it manifests as robbery.

Originally, the groups met each other on

occasions of tribal gatherings. If the groups were strangers to each

other, there would be greater formality - is this item equal in value

to that which i given in exchange?

In between the bargaining strangers, steps in the businessman,

the merchant, the trader. But it was not a profession originally. It

became a profession when the merchant figured out how to take something

for himself - something from both parties for the effort.

Professional traders arose when

this merchant activity was combined with long distance transportation.

The professional trader obtained goods where they were in excess,

therefore cheap, and and carried it to another location where it was

rare and therefore valuable. For example, when some adventurers from

the Baltic went south wearing amulets made of Baltic amber, they

discovered people in the south who fascinated by the amber jewelery and

gave something in exchange that was valuable to them.

We know how in recent North America Natives were

happy to receive beads in exchange for furs. So we may think that the

merchants were crooks to take valuable furs in exchange for cheap

beads; but the realty was that the Natives did not attach such a high

value to furs as Europeans living in cities and the Natives found

European beads amazing. I would take them much effort to make such

beads themselves.

In the Roman Age, and earlier, when the southeast

Baltic area was visited by Pytheas and Tacitus, they thought the

natives there for undervaluing amber so much they even burned it

sometimes for fuel, But the reality was only Pytheas and Tacitus

valued the amber, as a result of their experiences with it in the

Mediterranean market. Here in the north, it was something pretty that

washed up onto beaches after storms. Anyone could walk the beaches and

collect it. No payment needed for it.

But the reality was that the visitor from the

Mediterranean who came to purchase cheap amber, had already paid a

great deal in the transportation getting there.

The professional trader weighed the cost of

transporting an item a long distance against the difference between

cost at origin and revenue expected at the destination. Costs would be

kept down is the product had a high value compared to weight, and if

the shipping was as efficient as possible. In the beginning the people

who were able to make the journey for the lowest cost and highest

efficiency were those who used waterways and who had mastered,

now for millenia, a way of life moving through the natural wilderness

from one camping location to another, returning to the same place only

a year later. Such people could do the same thing, but carrying goods.

All that was necessary was that they maximized profit. If you had a

load of amber necklaces manufactured at the southeast Baltic, and made

a journey south up the Vistula, stopping and camping in four markets

along the way, you will not try to sell the amber necklace close to the

origins of the amber. You will hide the amber until reaching the

southern market where it is in greatest demand and fetch the greatest

payment, when weighed against the cost of the shipping. This is the

reason, it was in the interest for early traders to carry wares the

entire distance, and not sell it at the next market. If an item were

simply traded in the next marketplace, and it eventually reached the

south, its value would be consumed by a long chain of middlemen, each

adding cost, so that at the destination the net gain would be negative.

Therefore there was a strong incentive for the boat

peoples who embarked on professional trading, to deliberately set out

to go all the way to the final destination, even if it took many

months. Professional traders might imitate their traditional way of

life, moving through the settlement local markets a if traditional

campsites, spending a whole year before arriving back where they

started. It is possible that there were such trader, even travelling

entire families together. It is possible the peoples Greeks called

"Cimmeri", circumnavigated Europe, with the Volga on the east. It is

thought the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts, actually followed a

trade route that circumnavigated Europe.

It is surprising how even today archeologists do not

understand what drives trade. Archeologists have claimed the Baltic

amber that appeared in tombs of Babylon, arrived there by a chain of

hops from market to market. Others imagined that the the large amount

of amber that was found in the tombs of Mycenean kings came from a

large shipment presumably carried by their own people. But the

fact that today Polish archeologists were discovering remains of

amber-necklace crafting workships dating to that time (4000 years ago)

suggests that the Mycenean kings became aware of amber and its value by

already existing amber trade, in the Mediterranean before the Mycenean

Greeks arrived and began a campaign of replacing the original

"Pelasgic" trade language, with Greek.

In Finnic the stem

myy or

müü

means 'sell'. Was Mycenea a trade center established by the "Pelasgi"

and was it originally called MYYGI(N) from genitive of MYYK 'the sale,

selling' hence '(city) of the selling'.

Not long ago, there was a media article about

archeologists having found that about the same time, or earlier, there

was copper mining in northern Wales that removed more copper from the

mine than could possibly be used locally. The idea was advanced that

the copper was being removed by boats. Where did the boats go? Were

they carried by ship all the way to the east Mediterranean? When

ocean-going ships had developed, ships that did not need to be portaged

or suit rivers, and which could be propelled by wind, it was possible

to load them with ore, and if the sailors did not have someplace else

they had to be, the ship could take months travelling the sea, with no

cost than to feed the sailors.

With sailing ships, distance ceased to be a

challenge. The large distance was easily covered by ships that sailed

night and day. It was possible, for example, for a ship sailing with

the wind, night and day to travel from Britain to the southeast Baltic

in ten days. Never mind, the challenges of carrying goods by rivers,

with portages, navigating marshes, stopping at markets, camping on

shores. Trade by sailing ship became the most efficient manner of

shipping, and it was not limited to light things of high value.

The British Isles became a major source of ores

needed in more developed Europe. Tin had to be added to copper to

produce the harder metal - bronze. Around 500 BC (2500 years ago, the

Greek historian Herodotus wrote that "amber and tin" come to Greece

'from the ends of the earth".

The whole story of how trade, industry and commerce developed Europe is essentially unknown.

<<<CONTENTS

<<<CONTENTS

<<<CONTENTS

<<<CONTENTS