<CONTENTS

<CONTENTS

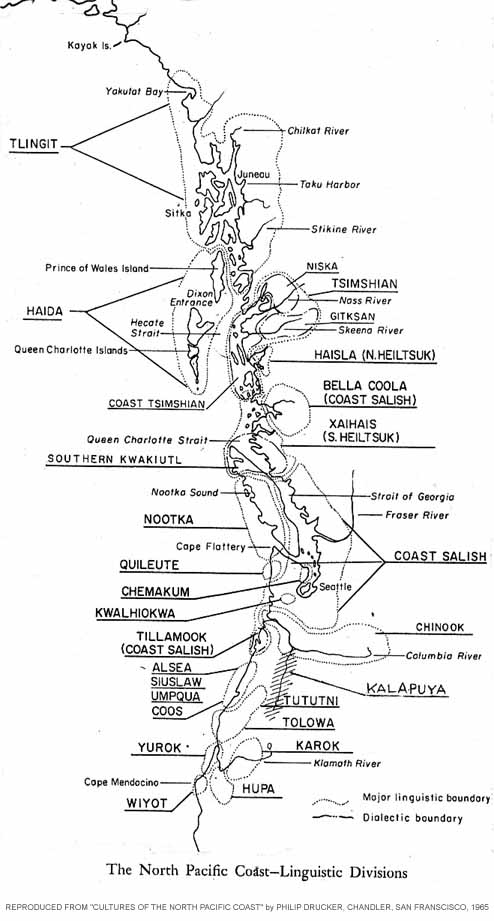

5. WESTWARD TO NORTH AMERICA

THE SEAGOING EXPANSION WESTWARD TO NORTH AMERICA

6,000-4,000BP

Synopsis:

The expansions to the sea of chapter 3, were still tied in some

way to their arctic Norway origins. But when the expansions went far

enough, such as into the Canadian arctic, or in some way as far as the

Pacific, we are speaking of migrations great distances. As remarkable

as it may seem to us, it was not really that remarkable. Whales migrate

up and down the North Amercan coasts of the Atlantic and Pacific

for many thousands

of kilometers. Peoples who have become dedicated to whale hunting will

rise to the challenge of traveling as far. They will settle

approximately at the half-way point of the whale migrations, so that

they will encounter them twice a year going south and then coming back

north. In

addition to following the voyages of whale hunters, I will also look at

the Alqonquian languages, that I believe were offshoots of it, since

arctic whaling and generally arctic sea peoples would have included

groups who were attracted towards the south, and found the flooded

postglacial landscape also yet uninhabited. These people would be the

Algonquian peoples, who developed an interesting skin boat that used

birch bark as the skin. There may be other examples of seagoing

bat peoples impacting North America, but I will present the

ones I discovered around the 1980's when I did research. Someone

interested in the subject is welcome to continue the investigations of

the expansions of boat peoples, including later expansions via

seatrade. Traditionally, the academic world has taken the evolution of

boats and seatrade for granted, and failed to recognize its

revolutionary impact on transportation including furthering the

evolution of long-distance-trade-based civilizations..

Introduction

OCEAN CURRENTS LEAD TO NORTH AMERICA

The most obvious expansion of boat peoples would be

the continuation of the internal expansion within Asia. Once reaching

the Ob River basin, boat-oriented peoples could move to other rivers,

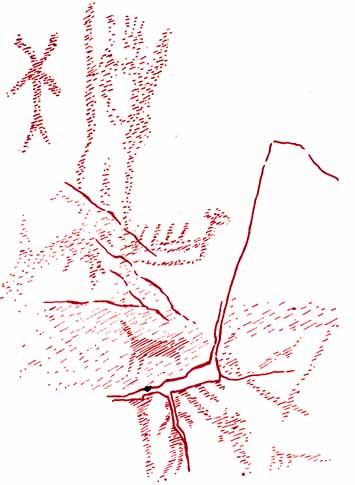

and end up travelliing the Lena, as proven by the image of a large

dugout found on a rock wall beside the Lena River. But the most

interesting and dramatic expansions occurred through the arctic seas

and some distance down the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. But,

arriving on the shores of North America, could then launch the boat

peoples into water-filled environments towards the interior, such as

the expansion of boat peoples into the east half of Canada into the

post-glacial environment that arose there.

Once there were boat capable of ocean waves - and the

arctic skin boats fit that requirement - migrations throughout arctic

waters was easy as land was close together. The notion that there were

contacts by boat, between Europe and North America via the North

Atlantic, or between east Asia and North America via the North Pacific,

at the earliest times, is so obvious that one wonders why it has to be

debated. If we show that there are certain words in common between

Finnic languages and Inuit language, should we be surprised? And yet,

scholars feel it is controversial and not obvious and needs to be

debated. In my view, this theory, as presented

here, should not even need to be a large issue. It is so obvious.

All we need to do is to establish that there were seaworthy skin boats

in arctic Norway some 6000 years ago - and this is clearly evidenced in

rock carvings; that there were people who harvested the sea; and that

there were sea currents that would have helped men in such boats to

venture towards North America into the North American arctic and down

the Labrador coast. Every requirement is present.

It is true there may be a need to

debate crossings through the centers of the oceans. Even oceanic boat

peoples tried to remain on courses that brought them to the shore where

they could find fresh water and food..

Crossing the centers of oceans and not seeing land

for weeks

would required plenty of fresh water on board, as well as food.

Did Polynesians cross the middle of the Pacific? Did sea peoples from

the Iberian coast cross the middle of the Atlantic to visit the

Bahamas? Were the latter "Atlantians"?.

There is plenty to debate

when we consider crossings through large spans of open water. But there

is no reason to debate the prospect of seaworthy skin boats following

the edge of sea ice, the coast of Greenland, and allowing ocean

currents to carry them. It is obvious even without plenty of additional

evidence.

Following the northern coasrts, there was plenty

of places to land, to fetch fresh water (or freshwater snow), and to

procure food along the way. There was nothing to hinder circumpolar

adventures if there were men with an adventurous spirit (or indeed, men

who got lost, but were still able to survive off the land and

sea.) The idea that ALL original arctic peoples were basically

the same people, from the same origin, should be an established obvious

fact in our body of knowledge. There is plenty of additional

evidence in folklore and technology - where we see parallels for

example between the Inuit and arctic Asians.

THE WORLD'S OCEAN CURRENT HIGHWAYS

Figure 1

This map of the world ocean currents suggests the paths of oceanic

migrations. The most applicable currents are those that follow coasts

as then the seafarers can land to replenish supplies. Note that when

the world is shown in a rectangular fashion the top and bottom of the

map stretches the continents. In reality distances in the arctic are

much smaller than they appear here.

The above map shows in pink the POSSIBLE migrations of the arctic

sea-going peoples. Note that the distances were much less than the map

suggests since the map stretches the polar regions.

The map shows migration west to east over top of Siberia. We do not

know if that occurred. It is possible to explain the arctic entirely

with n east-to-west migration. See our discussion of "Thule" culture

origins below.

We have already discussed in Chapter 3, the north Atlantic ocean

currents and how the circuits of currents could have developed three

divisions of seagoing cultures, all of which were oriented to the

warmed waters of the Gulf Stream.

More can be read from Figure 1. Looking now at the Pacific, we sea

currents crossing the Pacific from south of Japan across to

approximately the middle of the North America coast. around Vancouver

This is supported from the fact that trash from the Japanese tsunami

some years ago were beginning to wash ashore around Vancouver, starting

only some months later.

Note how the current, reaching the Pacific coast near Vancouver

turns in two directions, one branch going north and then circling back

to Asia in a counter-clockwise direction, and the other turning south,

and turning west near the equator.

Early seagoing people travelled with the currents, and did not want

to be out of contact with land for long. The prevailing winds were not

so important unless they raised sails. Even without sails there would

be waves, and preferred routes would be ones where the currents and

prevailing winds were in the same direction.

Analysis of possible routes taken by the prehistoric seagoing boat

peoples can lead to many useful conclusions. Considerations of the

timing and routes of whale migrations, and where archeology has

actually found evidence of human presence, can make the prehistory of

the seagoing boat peoples vivid. This article does not proceed into

detail. Our purpose is simply open the subject by

looking for evidence of boat peoples far from their origins. Part of

the evidence would be to find coincidences in languages between such

peoples, and the Finnic languages at the "Kunda" culture origins

location - so this investigation continues in the separate article

investigating the linguistic dimensions.

Devoted to Animals Hunted

'OWNERSHIP' OF WILD ANIMAL HERDS

Over the centuries a patronising mythlogy has

developed in civiizations that peoples living in harmony with nature

were like wild animals, mindlessly searching for food. But this has

never been true. Human survival in environments outside the natural

'Garden of Eden' environment in which humans evolved, required maximum

organizing and planning in their way of life. It is assumed that

intelligence and organizating was manifested as material culture. If

archeologists find remains of impressive palaces, or technological

works, they assume the people were 'advanced', but people who left

behind only campsites were verging on animal-like primitiveness.

The reality is that in general people in civilizations were more

intelligent and healthy because of the greater challenges of living

outside the artificial environments, than inside. Partly it is the

increased demands on the mind and body to live in harmony with nature

than in harmony with the posh artificial environments created in

civilizations. More humans can survive in the short term, but in the

long run the health of human populations declines. The eventual

collapse of civilizations in history, may be caused by civilization

creating a disconnect between its populations and nature, and

eventually there has to be a return to nature. It could be compared to

how farmers have to leave farm fields 'fallow', to reture their natural

fertility. Civilizations may have to collapse.

Therefore, we must look on peoples who lived

in harmony with nature possibly being true humans, while humans living

in civilizations being the weak and unhealthy. We are therefore dazzled

by material culture because we are indoctrinated by civilization to

feel that way.

The closer one studies the prehistoric, ancient, and

historic 'hunter-gatherer' peoples, the more amazed we can be about how

complex their society was. They did not develop buildings and monuments

for one simple reason - they were mobile. When farming was adopted in

humankind, the people could no longer be nomadic. Because people stayed

in one place, the infrastructure, the material culture, kept developing

generation after generations. An emperor could have a monument to be

developed by an army of slaved over several generations. Civilization

builds material culture on the last. The original nomadic humankind

could only develop small or non-material culture. For example, the most

developed cultures of poetry and song was in the northern material

cultures. Had there been writing, we would be celebrating northern

authors, rather than those of ancient Greece. We can only celebrate

that with which we can be aware.

Being in harmony with nature meant to have a place

within the plants and animals in the environment, similar to how, for

example, have a place in the lives of deer. But humans too organized

themselves into bands, packs, like for example, wolves, and claimed and

defended territories. Humans, competed not just with other

humans, but animals too. They

did not think so much about owning the animals as in terms of owning

the rights to hunt at particular sites as defined by their annual

rounds.

Hunters of large herding animals might become

dependent on them, especially if it was necessary to develop a

sophisticated way of life designed for that specific animal. For

example, living off reindeer herds required sophisticated practices for

hunting, and then exploiting all the products provided by the animal

that was available. (Every part of the animal was used in one way or

another) Hunters specialized on a particular herd animal defined

their territory in terms of a particular herd. Long before

domestication, the hunters of the herds thought of

themselves as 'owners' of those herds, and they both endeavoured to

foster the herd's health as well as defend them against foreign

hunters.

In the late Ice Age, the reindeer hunter tribes of

the North European

Plain would have stayed with the same herd generation after

generation. Their sense of territory was that herd, not the

land.

Each tribe respected the herd of the other tribe. There is no question

that something similar occurred with tribes that hunted horse and bison

herds.

Archeology says that the "Kunda Culture" from which

the expansion into the oceans came, originated around 12,000 years ago

from the "Swiderian" reindeer culture located in a wide area comprising

what is now Poland and surrounding region. These reindeer hunters would

have had contact with the expanding "Maglemose" boat peoples, and when

reindeer hunting or even pedestrian hunting in general became

difficult, they borrowed from the "Maglemose" culture, and the "Kunda

Culture" arose. The "Kunda" material culture inherited technology and

pracrices from their former reindeer hunting culture. I think they

inherited the highly nomadic nature of reindeer hunters, who, even on

foot covered a wide region in their wanderings to keep in harmony with

the great migrations of thousands of reindeer. The Baltic Sea was a new

liquid form of tundra, and they were not afraid of treating the sea as

a vast plain over which to move in accord with the behaviour of

animals. The reindeer of the sea were probably seals, since seals

congregated in herds. They found they could use technology inherited

from former reindeer hunting.

Thus, when the "Swiderian" culture moved into the

flooded lands south of the melting glaciers they did not become

pedestrian hunters pursuing individual animals,. but continued to seek

out the large herds, but now the herds found in the new liquid tundra.

When we get into the mind of men of the "Kunda"

culture we can understand their mentality - large scale seasonally

nomadic behaviour over the liquid tundra, and the pursuit of the sea

mammal herds. Besides seals, there were the walrus herds, dolphins, and

the whales.

But it was the whales that travelled especially long

distances and those descendants of the "Kunda" culture that became

hooked on whales, would have made especially long voyages. We do not

know, but it is possible whale hunters could have travelled as far

south as whales migrate. Archeologists and geneticists who find

evidence suggesting northern sea peoples somehow reached southern

regions along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, should consider whale

hunters.

In about the 1980's I pursued this question of

whether whale hunters travelled very far down the coasts. In terms of

migrating south along the European Atlantic coasts, such an

investigation is thwarted by the amount of development. Aside from the

Basques, there are no coastal peoples who have any connection to

aboriginal origins. But the Basques are interesting because when Europe

developed a great demand for whale products, Basques were quick to

respond. Originally whale products were obtained from Greenland Inuit

who hunted whales in a traditional way, but Basques quickly dominated

the whaling industry. Was there something in their culture that had

preserved an association with whaling? We will look at the evidence in

the Basque language.

It is of course possible that whalers also travelled

south on the North American coast of the Atlantic. Later in this

article, I will look at evidence of an origin in arctic skin boat

peoples, in the Alqonquian peoples. I do not know if evidence of

whaling peoples can be found further south.

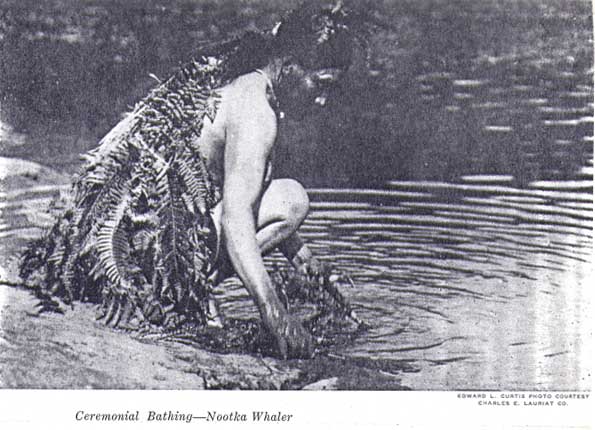

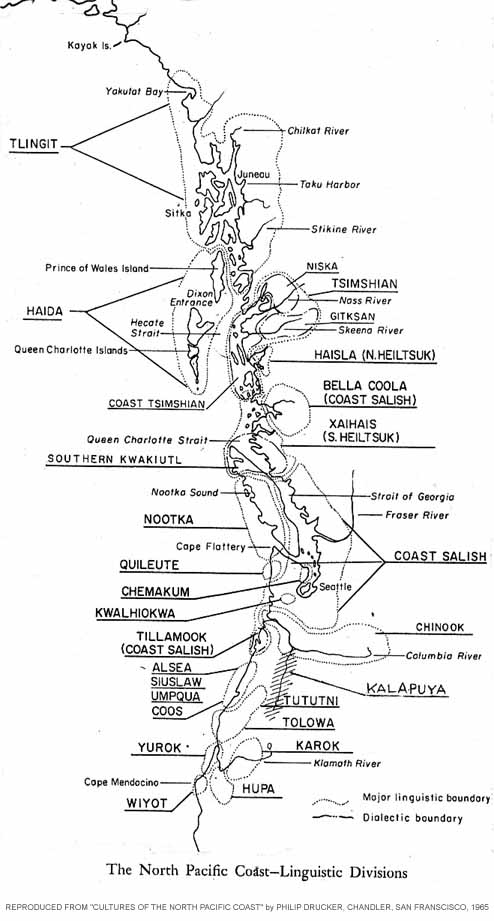

Investigations of the Pacific coasts are more

fruitful. On the Asian side, it is possible the Ainu peoples of

Japan, originated from the same peoples who became the "Inuit".

On the North American side, my investigation of indigenous languages

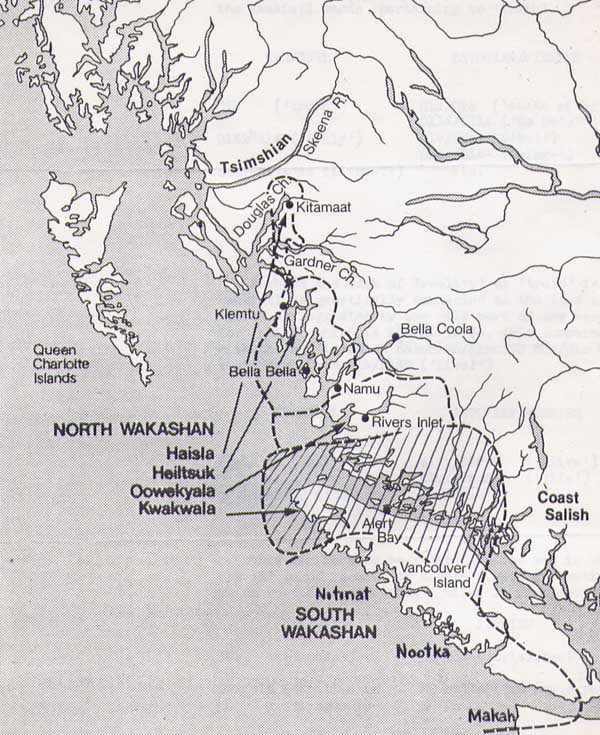

down the coast lead me to discover the "Wakashan" cultures of the

Vancouver area had deep whaling roots. Furthermore archeology confirms

that originally the coast was unihabited and became inhabited from

about 5,000 years ago, which is consistent with the development and

expansion of seagoing skin boats from arctic Scandinavia. Other peoples

with whaling traditions on the coast apparently came to the coast from

the interior at a later time and adopted the whaling practices.

The Pacific coast of North America, particularly the

British Columbia coast, also demonstrates how material culture develops

when people stop being nomadic. Because of the wealth provided by

the rain forests and salmon, the British Columbia coastal peoples did

not have to remain nomadic. As a result they were able to develop their

material culture, which included totem poles and cedar lodges.

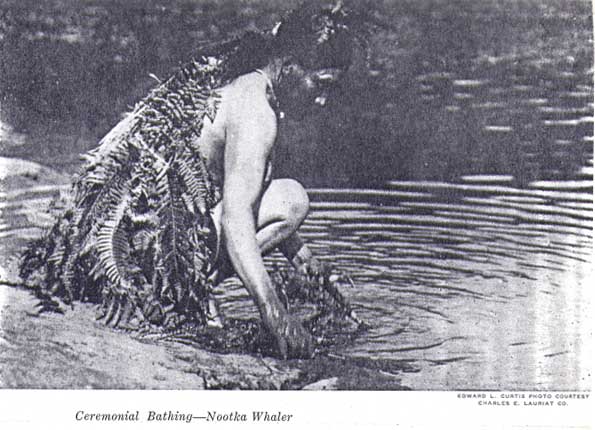

The salmon runs up the rivers provided plenty of food, so that whale

hunting became more of a cultural tradition than a necessity,

Situated approximately half way in the coastal migrations of the

whales, they could access the whales coming or going. Culture can be

defined as an originally necessary activity, now not necessary, but

preserved in rituals and ceremonies.

Whaling was of

course difficult, so more realistically, most of the year was probably

spent harvesting the smaller creatures, whether it was plentiful fish or the smaller aquatic animals such as seals and walrus..

The Arctic Sea-People of North

America and Greenland - the "Thule" and "Dorset" Archeological Cultures

ARCHEOLOGICAL

CULTURES OF THE ARCTIC

Archeologists say that the Inuit of northern North

America and Greenland, originated from the archeological "Thule"

culture, which expanded rapidly west-to-east (in 500 years!) from

northern Alaska. The name "Thule" has no relationship to the historic

Thule of Pytheas which is

believed to refer to Iceland, and which coincidentally matched the

Finnic word for 'of fire' ("tule" (DUH-LEH) in Estonian). The new

culture, the new

technology, seemed to displace a former "Dorset" culture in the north.

The "Dorset" culture had arrived much earlier from the Greenland side,

beginning as early as 3000BC (5000 BP) about the time of the making of

the rock

carvings of seagoing skin boats.

Note that archeology

defines culture by artifacts. The replacement of "Dorest" with "Thule",

only means that a new set of tools and practices travelled east from

Alaska. It does not necessarily mean a massive migration of "Thule"

people. The new ways could have spread through contact, intermarriage

with minimal genetic replacement. Realistically it was both.

Archeologists tend to want to invent drama - wars and conquests. But it

is now accepted that MOST spread of material culture innovations rise

from simpy copying of the more attractive culture. This is clear today

from the speed at which the whole world has adopted the internet and

cellphone. If a people with new superior hunting tools came on the

scene, it would be adopted and spread much more quickly than the very

laborious process of immigrants actually conquering and killing off the

natives. Only genetics can determine if there was genetic replacement -

but even that is not easy to determine because of intermarriage.

I have, thoughout my investigations of the

prehistory of the Canadian arctic, not found any reason to believe that

a "Thule" people actually conquered a "Dorset" peoples, as opposed to

being the source of new cultural innovations that came to be widely

adopted. Humans fight over territory, and there may have been battles

at walrus congregating sites, but those battles could have been between

people with the same culture. The myth of "Thule" culture peoples

exterminating "Dorset" culture peoples is simply naive and absurd, even

if claimed by highly respected scholars. One culture simply changed

another, in much the same way that in modern history, an internet based

culture has replaced the print and letter based culture of a century

ago. Today we do not see any army spreading all over the world from

Google and Apple corporations, and killing off all people who do not

have Google or Apple products. Even in ancient times, nobody

exterminated existing peoples - only opposition. Conflicts are always

territorial - one group of men trying to 'win' in a competition

with another group of men. If other people than the warriors are

affected it is only collateral damage. But history has always

celebrated wars and victories, just as today men celebrate the victory

of their favourite football team over the 'enemy' team. History is not

about real events, but about wars - who won over who in the course of

time. Winning a war did not mean the entire population of the

defeated was destroyed - only the actual participants in the war or

competition.

If the "Thule" culture was merely the movement of an

innovative culture from the west to the east, then how did the "Thule"

culture originally arrive at the Alaska region?

If we assume the skin boat was developed in arctic

Russia and Scandinavia, then it could have travelled not just west

across the North Atlantic, but also east along the arctic coast of

Siberia. While it is generally accepted that the "Dorset"

material culture arrived in northeast North America from the east over

the North Atlantic, how did the "Thule" skin boat peoples arrive in the

northwest North America, at Alaska.

There are two possibilities: 1. that some of the

peoples who reached the Russian arctic migrated east along the coast of

Siberia and reached the Bering Strait and Alaska that way. 2. That it

originated across the north Atlantic like the Dorset at a time when it

was possible to travel by boat to the northwest.

The latter needs explaining: We know that about the

time of the Norse landings on North Americam shores there was a

climatic

warming that led to Norse establishing farms on the Greenland coast.

Within a few centuries the climate cooled again and those farming

settlements were abandoned. During this warming spell, passages between

the arctic islands, normally blocked by ice could have been free of

ice, offering easy passage to seagoing tribes (ie carrying the "Thule"

culture) on the west side. To be specific, McClure Strait-Viscount

Melville Sound, Barrow Strait, could have had ice-free passages

easy to follow in skin boats. It is believed there was a similar

climatic warming at the start of the modern era ( ie after 0 AD). The

"Thule" culture could have originated from the earlier "Dorset" culture

at an earlier time moving in the other direction (east to west) when

water passage was easy. and then movement across the arctic was blocked

off so that cultures on either side would have developed independently.

Therefore it is not necessary to find the "Thule"

culture emerging from a different ultimate source than the

"Dorset". They could both have come across the North Atlantic,

and then the originally single people become separated by a climate

cooling - until the next warming opened the passage again.

Which explanation works best? The problem with the

migration along the Siberian coast as a few shortcomings. First of all,

the Gulf Stream wamed waters was in the Norwegian arctic, and the

northeast Atlantic, and it would have drawn more seagoing hunters

there, thus increasing the probability of some groups continuing

west. Secondly the Tamir Peninsula extends so far north, that the

sea would have been frozen and blocked continuation eastward along the

coast. Thirdly, I have not learned of any seagoing skin boat

traditions along the Siberian arctic coast. All things

considered, it seems to have come from the east over top of North

America. The theory that passage was blocked and the east and west

populations developed independently for a time, makes much sense,

especially since Greenland Inuit speak of origins towards the east, and

yet their language is a dialect of Inuit. This also supports the idea

that the "Thule" and "Dorset" cultures were basically the same people,

and that all that migrated was material culture

SHORTCOMINGS

OF ARCHEOLOGISTS' MATERIAL CULTURES

Archeology only studies the hard material

remains left by people. Their definition of "cultures" according to

artifacts can be highly misleading. For example we mentioned above the

"Kunda" culture; but were the "Kunda" culture really very different in

linguistic and cultural terms than the "Maglemose" culture? Similarly

were other "cultures" to the north and east really very different from

the "Kunda"? We have to recognize that people of the very same

ethnicity and language -- with only dialectic variation -- can follow

different ways of life! The differences are determined by the

forces in the environment in which they lived, and not by internal

changes. Indeed internally they could all remain the same, changing

only the technology and behaviour that they needed to deal with each

their own environment. Seagoing people developed material culture

suited to seahunting, river people developed material culture suited to

river life, marsh and bog people had yet other technologies and

behaviour. Humans can change their material culture very very

quickly and still remain the same, ethnically. For example, Chinese can

adopt American business-suits and cars and electronics, and still speak

Chinese, still eat their own traditional food, and still carry on their

own folk traditions. Another good example are Estonians and Finns. They

borrowed farming practices and from an archeological perspective they

ought to be Germanic speaking, but they are not.

Thus we have to be careful about assuming that the

"Thule" and "Dorset" archeological cultures were different ethnically.

While scholars have painted pictures of "Thule" people travelling east

from the Alaska region, and killing off all "Dorset" culture they met,

to be realistic, people living in the arctic would not have waged any

war except if either the invaders were often seen 'stealing' their

resources, or the invaders were stealing "Dorset" culture sites (sites

where arctic animals congregated in quantities, for example) and needed

to displace the indigenous rivals to survive. Otherwise the changes

occurred through positive influences. It is clear from archeology that

the "Thule" material culture was superior, and so the most logical

explanation, as already described above, is that the original

"Dorset" culture people became aware of the "Thule" innovations and

adopted them - a very common process. It is not necessary for the

originators of a new advantageous cultural development to be physically

carried by migration, for the innovation to spread.

A single "Inuit" language is found across the entire

North American arctic from the Bering Strait to Greenland. There is no

evidence of another language. The explanation that the "Thule" culture

killed off every "Dorset" culture follower does not make sense. If my

interpretation above is correct, then the "Thule" and "Dorset" culture

practitioners spoke the same language, with only dialectic variation,

and all that happened was that through contact and intermarriage the

strong aspects of the both cultures survived. For example, the skin

boat of the Greenland Inuit, based on wrapping a large skin with poles

on either end, around a frame, was not like the skin boat in Alaska

where the skin was not easily removed. Here is a case where the

"Dorset" version of the large umiak was superior to the "Thule" version

near Alaska - resulting in the Greenland Inuit continuing to use it

until the 18th century, as revealed in an illustration printed in a

book at that time.

Material culture, and soft culture like language and

genetics are independent of one another. While they can move in

parallel, often they evolve independently. Unfortunately archeologists

do not recognize enough that a material culture can spread without any

respect for language or genetics. Similarly language too can spread

independent of genetics - although in this case I think there was a

single language across the North American arctic and other than

dialectic peculiarities, this aspect does not apply. The only true

insight into whether there was actual migration and warring, lies in

genetic research. Was there any clear indication of genetic replacement

in the northeast arctic by genes from the northwest arctic.

AN EARLY CIRCUMPOLAR LANGUAGE

It is well known in linguistics that languages

change according to useage. Words that have to be used daily will

continue to be used generation after generation. Language changes when

words are used infrequently so that now and then a speaker does not

remember the word, and selects another word. We do it all the time if

we cannot recall the name of something. In a society with writing, the

various words can be remembered, and so there are many synonyms, but

without writing, words develop and endure according to how used they

are.

Therefore we would expect that if there

was a common arctic circumpolar boat people language many thousands of

years ago, that to the degree the seagoing tribes became established in

various regions and reduced contact with more distant neighbours,

dialects would have developed. But throughout the region words used all

the time throughout all these peoples would endure for a hundred

generations.

Historical linguistics compares similar words in different languages

to observe the ways in which the words have changed phonetically in

different directions. They then try to reconstruct how the parental

language sounded originally, before the descendant languages shifted it

in one direction to another. However historical linguistics is

dependent on finding the similar words to analysis. The further back we

go, the fewer words we can find; but even finding a small number of

similar common words is enough to determine distant origins. We need

only become suspicious with uncommon meanings. They are likely to be

random coincidences.

The words most resistant fo change would be words

used daily in the household - words for family relationships, for

example. If the distance between the Inuit language and the

Finnic language is some six thousand years or so, we certainly cannot

expect there to be very many examples of similarities.

The source of the Inuit words and

expressions tested in my brief study included only a few 1000

expressions. (The

Inuit Language of Igloolik, Northwest Territories,

Louis-J Dorais, University of Laval, Laval, Quebec, 1978). My source of

Finnic words is my own upbringing. I know all the most common Estonian

words from learning it in childhood. It is those most common words

imparted to children that are the ones that are probably the oldest.

So was it true? Do the words I saw in Inuit that had

strong resemblances to Estonian, both in sound and meaning, belong to

common ideas that would be used every day?

As expected there weren't many words, but even so,

the rate at which I sensed similarities between Inuit words and

Estonian words was significant: about one

word in 55.

The following area few of the best examples,

because the words relate to the most common concepts and indeed they

have changes so little that the connection to Finnic is

believable. (For more detail, see the Supplementary Article - see

the links at the bottom of this page)

THE RESULTS OF ANALYSIS OF INUIT WITH FINNIC

First it should be noted that Inuit grammar is

as expected from the passing of some six millenia. The Finnic

"agglutinative" structure (endings can be added to endings to form a

complex thought) can be viewed as a degeneration from a "polysynthetic"

form (small prefixes and suffixes added to stems to form complex ideas

in single words) There are also similarities between Finnic and

Inuit grammar. The

most noticable is the use

of -T as a plural marker, or -K- to

mark the dual. (Although neither Finnish nor Estonian retains

declension of a dual person, it is easily achieved by adding -ga

'with' into the declension, which is the Estonian commitative case

ending.)

among Inuit suffixes, the one that

leaps out first is the suffix -ji as

in igaji 'one who cooks'. This

compares with the Est/Finn ending -ja

used in the same way, to indicate

agency, as in õppetaja 'teacher, one who

teaches'. Indeed Livonian

(related to Estonian) uses exactly -ji This ending would have been in common use, so there would have been an ancestral version that has survived millenia.

In Inuit there is -ajuk as in tussajuq

meaning

' he sees for a long time' or the similar -gajuk which makes the

meaning 'often'. This compares with Estonian/Finnish aeg/aika meaning

'time'. This pattern has parallels in Algonquian Ojibwa language

(people of the birchbark skin boat)

Inuit kina? 'who?' versus Est./Finn. kelle?/kene?stem

for 'who?' This can be debated on the exact forms, but in general

what we see is the use of the K for interrogative pronouns. . Note the

use of K for interrogative pronouns, signifying the K sound marks a

question. Such parallels in grammatical elements, is evidence that the

similar words are a result of descent from the same language and not

borrowings.

Continuing to words, we should look first to family relations and then to daily activities.

Words for family relations are words not

easily removed, and Inuit produces more remarkable coincidences: Inuit

ani 'brother of woman',

compares with onu 'uncle' in

Estonian, but in

Finnish eno

means almost exactly as

in Inuit, 'mother's brother'. When we consider that over

millenia, these slight shifts in meaning can be expected, these parings

with Finnic words do not need to be debated.

Inuit akka

refers to the 'paternal uncle'. In

this case Estonian uses onu

again, but Finnish says sekä

'paternal

uncle' which is closer.

Then there is the Inuit saki meaning

'father, mother, uncle or aunt-in-law'. In Estonian and Finnish sugu/suku

means 'kin'. The Inuit word meaning suggests an institutional

social unit consisting of the head of a family being one's father and

his brother, plus both their wives (our mother and aunt-in-law) As I

wrote above, Inuit culture was based in hunting, and the male who

hunted ruled the society. The brother was both the assistance to

hunting, and the substitute if the other became incapacitated. This is culturally known, The loss

of the hunter, cold spell the end of the whole family dependent on

them. This may have been the original meaning of the Finnic sugu/suku,

but that when the Finnic people left the hunting way of life millenia

ago, the meaning became blurred and generalized, in much the same way

we see above the Finnish eno means 'mother's brother' while Estonian has narrowed it in onu to just 'uncle'

Inuit has amauraq for 'great grandmother' a

word that might reate to Inuit maniraq

'flat land' . These two words

relate to Estonian/Finnish ema /

emän- 'mother/lady-' on the one hand,

and maa/maa 'land, earth,

country' on the other. As I discuss

elsewhere, early peoples saw the world as a great sea with lands in it

like islands, thus the original concept of a World Mother was that she

was primarily a sea. Thus the original word among the boat peoples

for both World Plane and World Mother was AMA. The meaning of AMA did

not specify land or sea. The proof of this concept seems to be found in

Inuit maniraq since it

contains the concept of 'flat', as well as in

Inuit imaq 'expanse of sea'

which expresses the concept of 'expanse'.

Estonian too provides evidence that the original meaning of AMA was

that of an 'expanse', the World Plane. For example there is in Estonian

the simple word lame

("lah-meh") means 'wide, spread out'. There are other uses of AMA which refer to a wide expanse of sea. One

manifestation of the word is HAMA, as in Hama/burg the original form of

Hamburg . Also there is Häme, coastal province of Finland, etc. which

appears to have had the meaning of 'sea region'. Historically,

according to Pliny, the Gulf of Finland was once AMALA, since he wrote

that Amalachian meant 'frozen

sea' (AMALA-JÄÄN). The words for 'sea' in

a number of modern languages, of the form mare, mor, mer, meri can be

seen to originate from AMA-RA 'travel-way of the world-plane'. The

equating of sea with 'mother' interestingly survives also in French in

the closeness of mère

'mother' to mer

'sea'. The

intention of this

discussion is to show that the worldview appears to be a deep one,

possibly being born when boat peoples expanded into the open sea some

10,000 years ago,

However, we must also note that while

Inuit

'great grandmother' is amauraq,

the actual Inuit word for 'mother' is

anaana Is it possible Inuit

used N to distinguish between the sea-plane

and land-plane. Indeed their word for 'land, earth, country' too

introduces the N -- nuna. Or

perhaps the N is borrowed from the concept

of femininity because we also find Inuit ningiuq 'old woman' and

najjijuq 'she is pregnant'

which relate to Estonian/Finnish stem

nais-/nais meaning 'pertaining

to woman'. It is worth noting that we find a similar word in Algonquian

Ojibwa, notably I bring the passage from later into this

paragraph "Another Ojibwa word element with coincidences in both Inuit

and Estonian/Finnish is -nozhae- 'female'. The Ojibwa nozhae is very close to Estonian/Finnish nais-/nais-, and with exactly the same meaning. Estonian says naine for 'woman', genitive form being naise

'of the woman'" Such connections with Inuit help support my

theory that the Algonquian languages descended from earlier skin boat

peoples established in the northeast arctic of North America, perhaps

the "Dorset" culture ot their ancestral culture.

Inuit also says amaamak for 'breast'

which compares to Estonian/ Finnish amm/imettäja

for '(wet) nurse'.

There is aso Est./Finn. imema/imeä

'to suck'. These coincidences are strong indications of prehistoric

connections, and I don't think a debate about this pairing can be

defeated.

Inuit puvak

'lung' connects well with Estonian

puhu 'blow'. Finnish has

developed the word to mean 'speak'.

In Inuit there is -pallia as in piruqpalliajuq

meaning 'it grows more and more. This compares with Estonian/Finnish

palju/paljon 'much, many'.

Inuit also has the expression pulliqtuq

'he

swells' which compares with Finnish pullistua

'to expand, swell'. The P+vowel form is commonly found in language in

association to expansion, to blowing something up, as in English "ball".

Of common daily activities we have the following:

Inuit nirijuq 'he eats' versus Estonian närib 'he chews' This one can be debated, because ninjuq omits the R sound. Why not compare it to Estonian nina 'nose'

('nose in food'?) This one needs more information, from within the

language, derivative words, associated concepts. We need not leave any

hypothesis because the connection is not obvious.

But, the words which are of greatest

interest are words for 'water'. If there is anything that all the boat

people have in common is the act of gliding, floating, on water.

It appears that in Inuit the applicable

pattern is UI- or UJ- same as in Estonian/Finnish. uj-, ui-, Inuit

uijjaqtuq means 'water spins'

whose stem compares with Estonian/Finnish

ujuda/uida 'to swim, float'.

Interestingly Inuit uimajuq

means

'dissipated', but Estonian too has something similar in uimane 'dazed'

, demonstrating that both use the concept of 'swimming' in an abstract

way as well. (Indeed the concept at least survives in English in the

phrase "his head swims" to mean being 'dazed'.) Considering the Inuit

infix -ma- meaning 'in a

situation, state', it seems that the stem in

both Inuit and Estonian cases is UI, and that -MA- adds the concept of

being in a state, situation.

Then there is in Inuit

is

kaivuut 'borer' which

compares with Est./Finn. kaev/kaivo

'something

dug out' today commony applied to a hole dug out of ground. This

is very close, especially between Inuit and FInnic

Inuit qaqqiq

'community house' versus Estonian/Finnish kogu/koko

'the whole, the gathering'. This pair too, matches in form. The

concept of 'community house' and 'gathering' are identical, other than

an indication of a building. The shift that added the concept of a

building could have arisen from the fact that in the arctic, community

gatherings tended to be in the interior of buildings, and not in some

open air location.

Inuit alliaq

'branches mattress'

compares with Est./Finn. alus/alus

'foundation, base, mattress, etc' This pairing too makes sense.

All that differs is the reference to the matress being made of

branches. How far in the past has it been since Finnic peoples slept on

branches matresses?!

Inuit katak 'entrance' versus Est./Finn. katte/katte

'covering'. This too is very believable. The Inuit building had

entrances covered with a skin, thus if it began in the meaning

'covering', it acquired the meaning of 'entrance'. This was especially

true of winter during which people lived in large snow houses, where

the only covering was at the entrance.

Inuit kanaaq ' lower part of leg' versus

Est./Finn kand/kanta

'heel'. This is a good example of the word form and meaning being very

close. The lower part of a leg is in deed the heel. The

Estonian/Finnish version is a little more focussed towards the heel. I

would not debate this one more. But see next.

Inuit kingmik 'heel' versus Est./Finn king/kenkä 'shoe'

Here the word for 'heel' resonates with the Est/Finn word for 'shoe'. A

shoe is a covering for the heel. Difficult to debate this one.

Inuit tuqujuq 'he dies' versus Est. tukkub

'he dozes'. The Estonian word is a colloquial word, that may have

survived because it come into such common use. Since a person dozes

daily, the chances are that the word survived in Inuit in the meaning

of 'sleep' and only became transferred to the idea of 'death'

relatively recently.

Inuit angunasuktuq

'he hunts' or anguvaa 'he

catches it' compares with Est./Finn öngitseb/onkia

'he fishes, angles'

or hangib/hankkia

'he

procures, provides'. The liking of hunting to fishing is not a problem

because seagoing people hunting was identical to fishing. I find this

paring is easy to argue and that more supportive evidence is available.

Inuit nauliktuq

'he harpoons' versus

Estonian/Finnish naelutab/naulitaa

'he nails'. But closer to the

concept of harpoon is nool/nuoli meaning

'arrow'. (Some words

here have echoes with English words - like to nail - because English

contains a portion of words inherited from native British language

which was part of the sea-going people identifiable with the original

Picts. Some also have echoes with Basque which also has connections

with ancient Atlantic sea-peoples) We will refer to harpooning further later, as we find the same word in the Kwakiutl language!

Inuit iqaluk 'fish' versus

Est./Finn. kala/kala

'fish'. This pairing can provoke major disageement among linguist. However, all we need

for a closer parallel in form is to have the intial "I" in iqaluk to be

dropped, because then we have QALU- It is because of this, that I

accepted this paring. It is easy to drop an initial "I" in Finnic from pure laziness.

Inuit unnuaq 'night' compares with

Est./Finn. uni/uni 'sleep'.

Here there is lack of parallelism between 'night' and 'sleep', however

it is possible that the parallelism would be valid if originally the

night was seen as the day being asleep. For an animistic worldview, the

day can be viewed as a living entity that goes to sleep. While we

cannot know for sure, the probability if high that this pairing of

words is valid.

The Inuit aqqunaq 'storm' is reminiscent of

the earlier word akka for

paternal uncle. It may imply that the storm

was considered a brother of the Creator. The word compares to the

Finnic storm god Ukko. In

Finnish ukko also means 'old

man'. Inuit also

has aggu 'wind side', which

implies the side facing the storm. In

Estonian/Finnish kagu/kaako

means 'south-east'. Prevailing winds

travelled from the north-west to the south-east; thus the word may

originate in a relationship to wind. Looking at all the evidence as a whole, the probability is very high, that Inuit aqqunaq is indeed mirrored in the Finnic words. I believe that if this is investigated further, the evidence will get better not worse.

The Inuit kangia

'butt-end' compares with

Est./Finn. kang/kanki 'lever,

bar' or kange/kankea

'strong,

intense' Here is another example of the Est./Finn. words having

more than one modern meaning. The 'butt-end' is the 'tail end',

the non-business end. The business end of a lever, bar, is the end that

is put under the object being leveraged. In a lever, the tail end is

easy to move. The business end is magnified and strong. It makes sense

that kange/kankea

would mean 'strong,

intense'. I think it is not difficult to connect the concept

of the 'butt-end' as the 'strong end'. I do not think there is a

debate possible that can defeat this pairing.

In Inuit traditions and indeed throughout the

northern hunter peoples, the man was always the hunter. This is

reflected in Inuit ANG- words. We have already noted anguvaa 'he catches it'. There is also angunasuktuk 'he hunts', which is obviously related to anguti 'man, male', and angakkuq 'shaman'. Estonian kangelane,

'hero', but literally 'person of the land-of-strong' may have a

relationship to the concept of 'shaman', and also to the earlier Inuit

concept within kangia

mentioned above. In general we see here another example of an

intense focus on hunting in both sea and land, and how hunting skills

were greatly valued. Much could be written on this subject when we

consider the way of life of the prehistoric boat peoples.

Inuit also has several KALI words that have Estonian/Finnish correspondences. Inuit qulliq 'the highest' corresponds with Est/Finn. küll/kyllä 'enough, plenty'; Inuit kallu 'thunder' corresponds with Est/Finn kalla/--- 'pour;; Inuit qalirusiq 'hill' resembles Est./Finn. kalju/kallio 'cliff'. In general it looks like there are many dimensions to the KALI words, and it occurs both in Inuit and Finnic.

The most interesting Inuit words to me, are tuurnaq 'a spirit' and tarniq

'the soul', because they compare with the name of the Creator across

the Finno-Ugric world. It appears in Finnish and Estonian mythology as Tuuri, Taara,

etc. And the Khanti still concieve of "Toorum". The presence of the

pattern in Inuit is proof that it has nothing to do with the Norse

"Thor", but that "Thor" is obviously borrowed from the indigenous

Scandinavian Finnic peoples.

Inuit uunaqtuq

'burning' relates to Est/Finn.

kuum/kuuma 'hot' but most

strongly to Finnish uuni

'oven'. This Inuit word obviously matches the Finnic uuni, very

closely. Even though the Finnish word means 'oven', in a world that did

not have ovens, it would have meant 'heating' which is caused by

'burning'. The conceptual connections are very close. In early

languages there were fewer words, and the precise meaning was inferred

from the context in which it was used. Over the last ,millenia the

number of words multiplied mainly because language was increasingly

used in situations where it was not being spoken directly in context,

and therefore words had to present more precise meanings. Thus it is

valid to imagine an original UUN+vowel word that had many

meanings, but all related to the production of heat, warmth.

Inuit kiinaq

means 'edge of knife'. This compares with Est./Finn küün/kynsi 'fingernail'

Both the Inuit and Finnic words describe the same type of object - a

thin blade with a narrow edge, It is possible in prehistoric

times the creation of a blade from flint, was seen as the creation of a

tool that was like a large fingernail. And then with the development of

metallurgy and metal knives the word was carried over into knives. I

have not problem with making this pairing.

Inuit aklunaaq 'thong, rope' compares

with Est./Finn. lõng/lanka

'thread'. While the Inuit word has the AK at front, everything else

with the pairing works. Note that in primitive times there probably did

not exist a word for 'thread' because a 'thread' would have been seen

as a very thin thong. When skin clothing or boat coverings were sewn

together, the thickness of the 'thread' used would vary greatly. There

was no basis for making a distinction between a 'thread' and a 'thong,

thin rope'. I am happy with this paring, although there is room

still for wondering about the AK- in front. Is it a prefix giving an

additional description to the thin rope? Was the original Est/Finn word

AKLANKA? But I don't think answering this question will

significantly alter this result.

Inuit words sivuniq

'the fore-part' compares

exactly with Finnish sivu

'side, page'. But also Inuit sivulliq

'past',

compares with the alternative Finnish use of sivu

in the meaning 'by,

past'. This kind of parallelism in two meanings, is powerful in

arguing a connection since it is not likely to occur by random chance.

In my opinion there is no debate about this pairing. It is interesting

to note that in these parallels, the Finnish word is closer to the

Inuit. This is to be expected since Finnish was located closer to the

northern regions around the White Sea, where our boat-people theory

suggests, the expansion of skin boat peoples began.

The following are a few remarkable parallels.

. In Inuit there is suluk 'feather' which

compares with Est./Finn sulg/sulka

'feather'. This is one of the

clearest parallels. This is also an amazing parallel. It suggests that

birds and feathers were very important. Perhaps feathers were a sign of

land nearby. We note that aboriginal peoples liked to wear feathers.

There must have been a major significant to prevent the word being

changed in form or meaning. Furthermore, we will see later that this

word also exists in the Wakashan Kakiutl language. See later.

The word may be related to the Inuit saluktuq 'thin' versus Est./Finn. sale/solakka

'thin' The Inuit stem is SALU which certainly resonates with the

Est./Finn. This is a good one, as it is a concept used every day. There

is always something that is thin. We may wonder if there is a

connection to 'feather'. I would not be inclined to debate this one.

In Finnic traditions there is a very strong

celebrating of water birds. They were a major source of food, and when

feathers were plucked off, there was a constant supply of feathers in

the household, and probably used for bedding and insulation. From that

perspective - if the the boat peoples carried these traditions to

arctic North America - it would not be surprising that the Inuit and

Finnic word for 'feather' would have survived.

This is just a sampling of Inuit words that resonate

with Finnic words. I use Estonian mainly, based on the fact that

Estonia originally had the "Kunda" boat people culture that - judging

from large harpoon heads - was the first to enter the sea, and which

then expanded north to the arctic sea, beginning at the White Sea.

While there is still an archaic theory created by linguists over a

century ago, that the Finnic languages began in the east and migrated

west, the truth from accumulated archeological information is that in

actuality it began in the Baltic area and expanded east. (As we see in

another article, it was the Asian reindeer people who migrated east,

and there was some mixing with the Finnic boat peoples.)

According to the new theory (not really new, as

archeologist Richard Indreko proposed it already in the 1960's)

the Estonian language is descended from the "Kunda" culture

peoples, in situ, (without coming from elsewhere), and that would

explain why Estonian resonates so well in the "Uirala" studies.

with the examples of indigenous peoples that can be linked to the

expansion of seagoing boat peoples.

The purpose of the above discussion of language is

not to come to any major linguistic conclusions but to show, based on

the scientific laws of probability, that what we found above is NOT

possible by random change. There is enough in my findings to confirm

the hypothesis that the Inuit culture ultimately arose from the same

parental circumpolar language of arctic seagoing peoples.

North American Algonquians - the Birch Bark Skin Boat and Rock Art

THE ARGUMENT OF ALGONQUIAN ORIGINS IN ARCTIC SKIN BOAT PEOPLES

The seagoing peoples of

arctic Canada would have been aware of a large land towards the south.

Since a warmer climate would have been attractive, the only thing

keeping any in the arctic would have been their being locked into a way

of life dependent on hunting animals of the arctic coasts and waters.

Immediately towards their south, moreover, there

were vast tundra deserts - land barren of life other than a short

period in summer. These barren lands would have been barriers to moving

inland in the southerly direction. However towards the northeast of

North America, there were ways in which arctic coastal boat peoples

could venture south and become aware of warmer, inhabitable lands with

enough animals to hunt.

In what is now eastern Canada, there were two coasts

by which seagoing arctic peoples could venture south while continuing

their seagoing way of life - south along the coasts of Hudson Bay and

south along the Labrador coast. But common sense suggests the

most inviting direction was the latter, down the Labrador coast, for

two major reasons - seagoing people in the vicinity of Greenland

would discover the north end of whale migration routes that went north

and south along the North American coast, The first peoples to

venture south would have been whale hunters. However whale hunters too

would have been trapped in a way of life that kept them out at sea and

only camping along coasts.

However when these whale huinters reached the waters

off the southeast coast of Newfoundland, they met up with the Gulf St

ream sweeping north and turning northeast alongside an shelf known

today as "The Grand Banks" that was rich with sea-life. It is here that

whale-hunters who also pursued fish, woutld find reason to linger and

inhabit the coasts nearby.

Of paticular interest to those who settled along the

coasts were salmon runs up and down rivers that drained to that

coast. Boat people could have followed the salmon inland into

yet-uninhabited post-glacial flooded lands.

Having originated from seagoing peoples with skin

boats, they would have discovered they were able to substitute birch

bark for animal skins, as a covering for their boats, and expanded

quickly through northern lands that were rich with paper birch..

The story of the inland expansion of boat peoples is

obvious from the fact that these boat peoples defined as the

"Algonquian" cultures, were found by Euiopean colonists to be located

in all river systems that drained generally to the northeast Atlantic

coast of North America. The longest penetration towards the interior

occurred through migrating up the Saint Lawrence River into the Great

Lakes. Towards the south of the Great Lakes there were land-based

peoples. Possibly the "Iroquoian" peoples were descended from such

peoples, since the Iroquoian cultures were completely different from

that of the Algonquian. The Iroquoians were not nomadic, but created

settlements and farmed the surrounding lands.

The Algonquians, therefore are very interesting

peoples to study from the point of view of the expansion of boat

peoples.

Over the ages, there would have been intermarriage

between the original Algonquians and whatever land-based peoples they

encountered in their expansion. Such intermarriage and general contact

would have brought indigenous genes and language into the Algonquian

boat peoples.

Bur we cannot ignore the possible migration of

arctic boat peoples south along the coasts of Hudson Bay as well. There

were three major rivers draining into Hudson Bay, so it would have been

easy for boat peoples to travel up those rivers and find an

increasingly forested and inhabitable land, if they adapted to hunting

land-animals. There were annual migrations of carbou, and the

sparse forests and boggy lands contained the animal known in North

America as "moose" (In European English they are called "elk". North

American elk are called "red deer" in European English).

We cannot say how many arctic people inhabited the

post-glacial lands of the Hudson Bay basin from travelling south from

Hudson Bay, versus north from Lake Superior, but I tend to believe more

expanded north from Lake Superior than expanded south from Hudson Bay.

The reason is a simple one - boat people are more likely to

explore down-river from an inhabited area as they would expect more

inhabitable lands ahead, whereas if you explore from barren lands there

will be an expectation of more of the same barren lands. Furthermore

they would have to paddle against the current. It would only be when

the upriver southward direction was known, that paddling upriver

through barrent lands would be tolerated, in order to reach more

inhabited lands at the southern reaches of the river systems.(Boat

peoples on rivers travelled seasonally up and down rivers. The Cree

would have wintered as far south as the rivers would carry them.)

Returning to the Altantic origins, the northeast

Atlantic offered other large rivers than the Saint Lawrence by which

the ancestors of Algonquians went into the interior. One nortable river

is the Churchill River that drained from the interior of Quebec into

the Atlantic. The people of that river were/are the "Labrador Innu" of

today. The Algonquians in Newfoundland or Nova Scotia were harvesters

of the sea and did not travel inland. The "Micmaq" are obviously

descended from peoples who remained there. But in New Brunswich the

"Maliseet" peoples inhabited the Saint John River. Other small

tribes were located in the water systems of smaller rivers drainging

into the Atlantic between the Appalachians and the Altantic coast,

south to around New York. The zied of a tribe was determined by the

productivity of the land, which allowed a tribe to occupy a smaller

geographical area than tribes (like the Cree) occupying barren lands

that required much greater nomadism to find food.

Focussing on the larger tribes that occupied the

east half of what is now "Canada", Europeans arriving a few centuries

ago found the "Cree" in the water basin of southern Hudson Bay,

the "Ojibwa" in the water basin of the Great Lakes north of lakes

Ontario and Erie, the "Algonquin: in the water basin of the

Ottawa River, the "Montagnais Innu" in the warer basin of the Saguenay

River, and the:Labrador Innu" in the water basin of the Churchill

River. All these peoples were located in regions without very

large trees - hence dugouts were not an option - but filled with birch

trees. All their boats were made by covering a

frame with birch bark. The birch bark canoe can be viewed as a form of

skin boat.

Algonquians further south, in what is now the

States, made dugouts, since birch trees were less available. The fact

that Alqonquian cultures knew both the skin boat concept and the dugout

concept, reminds us of the rock carving in arctic Norway that showed

both the skin boat and the dugout. This suggests the Algonquian

cultures most probably developed in the arctic, such as the "Dorset"

culture, or their predecessor culture, and migrated south.

If the Algonquian peoples descended from the north,

then the evolution of a skin boat from a dugout did not happen. The

Algonquians arrived with the skin boat concept already established.

Descending south of Hudson Bay or Labrador, they no longer had access

to the arctic animals they used for their skin boats. There may have

been memories of dugouts, but if they descended from the arctic, they

would not find the large enough trees initially. When their

original skin boats wore out, they had a problem of what to use for the

skin. Someone thinks "Why do we not stitch the bark of the birch

together to obtain the skin".

Continuing to spread southward into lands not yet

inhabited eventually came to an end as they encountered native peoples

in less flooded lands. They would have been pedestrian

hunter-gatherers, a woodland culture. Some cultural mixing may have

occurred. Once again, we should not think of one people dominating

another, but rather of new ideas being easily copied. The original

pedestrian hunter-gatherers would quickly copy the making and using

birch-bark canoes, and to some extent the way of life could spread,

even if the originators of the culture became a minority. (To

illustrate the idea of cultural change not needing ethhic change: In

recent history the Plains Natives of North America, copied Spanish

horseback riding, found some Spanish horses gone wild, and within a few

generations had completely changed their culture, but we would not

claim they were conquered by the Spanish! )

When we consider that humans are land-people,

and strong continuous pressures were needed to force a change that made

humans assume a new way of life dependent on boats, we cannot assume

that the development of the boat using way of life developed

independently from northing in North America. The evidence is not found

in North America. While northern Europe has rock carvings

dated to as much as 8000 years ago, showing both dugouts and skin

boats, all images in North America that show boats are relatively

recent. In addition, the ocean currents favoured voyages from northern

Scandinavia since there were locations where they could land to obtain

fresh water. For a journey in the opposite direction, the voyagers

would have to be prepared for a long journey with no place to land and

carry plenty of fresh water and food. It is not impossible, but

the expansion of seagoing peoples from east to west, first requires an

established seagoing culture with a reason to journey eastward (ie to

find new sites for hunting sea animals) which happened. Once it

happened, the expansion to North America was inevitable, and was

probably repeated often.

(This is not to say there were no other ways to

cross the Atlantic. Just as we can claim that the Norse crossing to the

northeast coast of North America was not the first, so too we can calim

that the crossing by Christopher Columbus near the equator was not the

first either. The real issue is not crossings, but whether those

crossings had any significant impact at the destination. A handfull of

men arriving on the North American coast would barely have had any

impact at all. Archeologists may uncover material evidence of

early crossings of the Atlantic, but unless the evidence is sustantial,

the group who left the evidence there might have had zero impact, and

the culture may not have lasted more than the lifetime of these

arrivals. But in the case of the Algonquians, we see a substantial

impact that seems to have come from seagoing North Atlantic peoples,

and lasted for many millenia up to recent history. With recent contact

with Europeans, the Europeans had already developed major ship

technology and were able to impact North America in a major way with

thousands of immigrants. Yhe native peoples of North America have been

impacted like never before to the extent of having the impact

assimilate them.

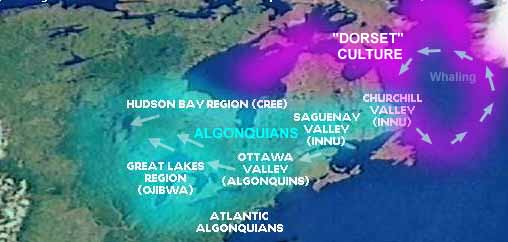

Figure 2

This

map shows both the expansion of the Algonquian tribes in blue, and the

seagoing the archeological "Dorset" culture.

EVIDENCE OF ALGONQUIAN PEOPLES ORIGINS

Other than the obvious connection between the

birch-bark skin boat and the animal skin boats of the arctic, the

Algonquian boat peoples origins is difficult to

fathom. To what degree did they develop their own way of life

independently, and to what degree did they borrow from skin boat

peoples in the North Atlantic and the North American northeast arctic

seas? There certainly must have been influences from the arctic, since

the Algonquian boat peoples had contact with the Inuit and previous

peoples in the north - such as around Hudson Bay and northern Quebec -

who did use the animal skin boat,usually walrus skin.

The arctic, according to our theory expressed

earlier, was

inhabited first by

the arctic skin boat peoples of the White Sea spreading around the

arctic coasts (which is not such an enormous distance - maps tend to

stretch the arctic.) And then the skin boat peoples were drawn

southward

by the warmth and many liked the warmth and adapted their arctic

culture to suit. I is certainly a good argument, that arctic skin boat

people groups who ventured south, would have remained in southern

locations that were not already inhabited. (When a location is

inhabited, newcomers are not free to do as they please, and are chased

away - except if the newcomers are considerably stronger and able to

displace the inhabitants.) Logically, if the lands flooded with

glacial water, were vacant since no boat peoples yet existed there,

then any people with skin boats from the north would have easily

inhabited those vacant flooded lands. .

Archeology describes two North American arctic

cultures - the "Thule" culture identifiable with the modern "Inuit"

culture, and the "Dorset" culture that preceeded it. Apparently the

"Thule" culture was originally in the northwest, around Alaska, and the

"Dorset" culture was originally in the northeast. The former apparently

expanded east, and overpowered the "Dorset". We are reminded of

an earlier discussion of how peoples pursuing the same resources are in

fierce competition and ultimately there would be one winner; and the

loser was driven away. However, the loser is not dead, but has to

adapt.

The one side killing off the other is never wise, so what would have

happened would be that the defeated people of the "Dorset" culture

simply joined the people of the "Thule" culture. Archeologically

speaking, it could simply be a matter of the spread of the superior

"Thule" material culture. It reminds us that archeologically determined

material culture is not genetic. The genetics of the original users of

the "Dorset" culture and the original users of the "Thule" culture

could have been genetically the same, and even spoken nearly the same

language. History offers many examples of how a new material culture

spreads without spreading the genetics of the originators of the new

material culture. There are examples all around us today, as all

peoples of the world are adopting the mass media material culture, and

everything carried in it. From this argument, it follows that the

Algonquian birch-bark boat peoples could in fact be descended

from the same genetic stock, at least in part, as the arctic skin

boat peoples, and becoming established much earlier than the period of

the "Thule" or even "Dorset"culture. There is considerable evidence in

the northeast quadrant of North America of elements coming from the

east across the North Atlantic. Besides the obvious spread of the skin

boat concept, there are some genetic markers, for example, which is a

subject of current debate regarding early crossings of the Atlantic

(and that the North American Native peoples did not entirely come

across at the Bering Strait land bridge, but also by boat at both the

Atlantic and Pacific sides.)

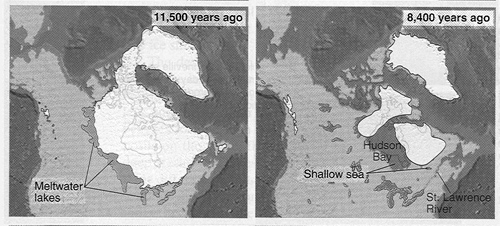

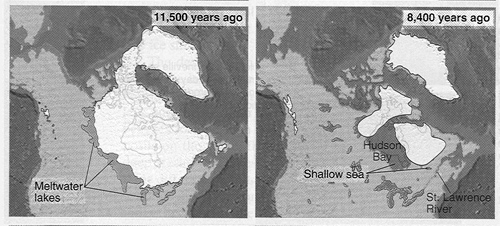

Figure 3

The above map shows the way the North

American glaciers retreated. Note that the regions that became flooded

with glacial meltwater was basically what is today the Hudson Bay

basin. Some groups of an arctic skin boat people, who had arrived

from the east, would have been able to descend either along the

Labrador coast, or the swollen Hudson Bay, and maybe both. It could be

that ultimately the Algonquian birch-bark canoes people may have been

the ancestors of Cree and that it expanded south, into the Great Lakes,

and then eastward, On the other hand, Atlantic skin boat peoples could

have easily descended the Labrador coast Do the Algonquians have

two origins paths?

The above map shows the way the North

American glaciers retreated. Note that the regions that became flooded

with glacial meltwater was basically what is today the Hudson Bay

basin. Some groups of an arctic skin boat people, who had arrived

from the east, would have been able to descend either along the

Labrador coast, or the swollen Hudson Bay, and maybe both. It could be

that ultimately the Algonquian birch-bark canoes people may have been

the ancestors of Cree and that it expanded south, into the Great Lakes,

and then eastward, On the other hand, Atlantic skin boat peoples could

have easily descended the Labrador coast Do the Algonquians have

two origins paths?

Furthermore, Greenland Inuit insist they originated

in the

east, while the Thule culture is supposed to have come from the west. I

think this is most easily explained by the theory that the "Thule"

material cutlure expanded, and not genetics. That way, people can think

of their ancestors (genetic origins) in northern Europe, while

technically their material was most recently the "Thule" culture that

originated in the west,

But that is not all. The interior Algonquian peoples

around the Great Lakes themselves carry beliefs of origins in the east

- which is at least consistent with a boat people expanding east along

the major waterway: the Saint Lawrence River that carries people to the

Great Lakes.

The fact that around 1000AD, the Norse were carried

by currents and winds to the shores of Labrador and Newfoundland,

suggest that such an event could have occurred from time to time every

since there were large seagoing boats in the North Atlantic. If as rock

carvings at the White Sea show, there were large seagoing skin boats on

the north European side as early as 6,000 years ago, then even if we

compute one accidental crossing every 500 years, that means in 5,000

years before the Norse there could have been unintented crossings

similar to the Norse crossings. Even earlier crossings, like some

archeologists claim, could have occurred if there was an independent

development of seagoing boats somewhere along the Atlantic coast during

the Ice Age. For example, if somewhere on the Atlantic coast, people

got into the habit of hunting animals on sea ice, they may have

developed ways of more easily reaching those animals. For example boats

based on the principle of the raft, such as reed boats, could have

developed independently of the development described here under

"uirala".(A raft-based boat would simply use the buoyancy of materials,

and not water displacement of the northern thin-skinned boats that when

swamped would lose their ability to float on top of the water.)

Besides the Norse crossing of 1000 years ago, there

must have been other earlier crossings. Newfoundland had up to historic

times a Native group called the Beothuks, whose culture first

manifested there in the early centuries AD. They could have come

south,or even originated from the northern British Isles.where one of

the names of the seagoing boat peoples there were called peohtas.

It is logical that during the period of the push of Celts into the

north, and then the Roman invaders circumnavigating the British Isles

and establishing control over all the isles, that many of the seagoing

"Picts" would have abandoned the area, and perhaps found a vacant

Newfoundland that was as good. The Beothuks was masters of skin boats

and canoes.

But such ideas are speculations arising from logical considerations.

Returning to hard data, what more is there that

suggests at least some cultural, genetic, and linguistic origins came

across the North Atlantic as that an early time (as early as 6,000

years ago)? :Less studied - or perhaps not studied at all before,

except here - is linguistic evidence of contact between the Algonquian

languages and Finnic languages of the original northern European boat

peoples.

In the course of investigating the traces of

expansion of boat peoples, I had a look at Algonquian languages, taking

the Great Lakes "Ojibwa" (or "Anishnabe") dialect for study.

The full study can be seen in a Supplementary

Article whose link is given at the bottom, but we can make some general

observations here.

Unlike our observation of the Inuit language across

the arctic that showed evidence of a language with the same genetic

origins as Finnic languages, our observation of the Algonquian

languages showed a different foundation language,but with Finnic-like

elements on top. My impression is that there was a mixing of an

original culture and newer ones which perhaps came with the skin boat

peoples across the North Atlantic.

The Finnic languages - looking notably at Finnish

and Estonian - look like a degeneration of the highly "polysynthetic"

language of the Inuit. Finnic languages have words that seem to contain

a large number of prefixes, affixes, and suffixes .Degeneration takes

the form of these elements being frozen into words, while in Inuit, the

prefixes, affixes, and suffixes are largely still free to use to invent

word-phrases as needed.

At the roots of the Algonquian languages is the

grammatical distinction between animated and inanimated things - things

containing spirit and therefore alive, verse things without spirits and

therefore dead. While it is possible to see connections with Finnic