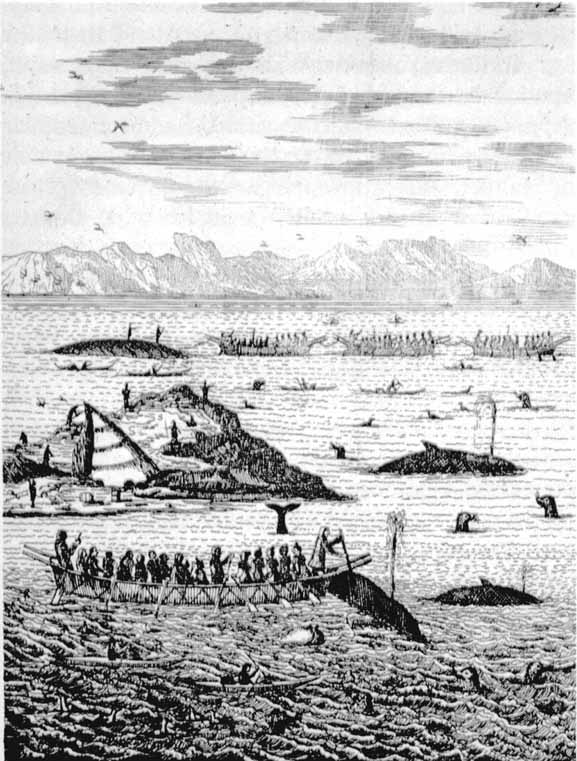

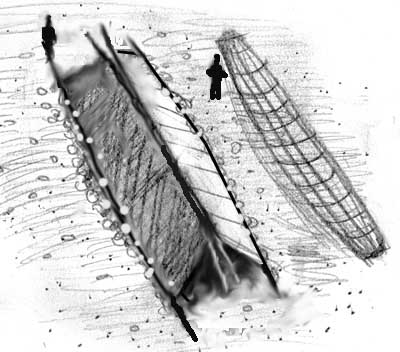

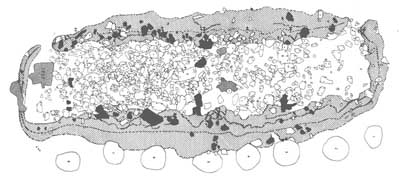

Greenland Inuit clans meeting to hunt

whales

from Description

de histoire naturelle du Groenland, by Hans Egede, tr

D.R.D.P., Copenhagen and Geneva, Frere Philibert. (Image adapted from

reproduction in Canada's

First

Nations: A

History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times by O.P.

Dickason,

Toronto, 1992. )

This illustration of whale-hunting is impressive. It

shows

clearly just how sophisticated the northwestern Atlantic seagoing

aboriginals were in terms of having mastered a way of life harvesting

the sea. What is shown must represent the culmination of

millenia of sea-harvesting traditions specially designed for the

North Atlantic, traditions that may date back to origins in arctic

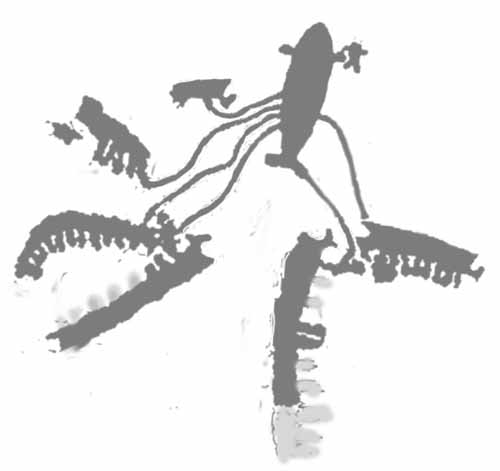

Scandinavia. I presented the following illustration from rock carvings

dating to some 5000-6000BC in

SEA-GOING SKIN BOATS

AND OCEANIC EXPANSION: The Voyages of the Whale Hunters

It is easy to imagine that the

techniques first shown in this prehistoric illustration are also

depicted in the illustration of the Greenland Inut,

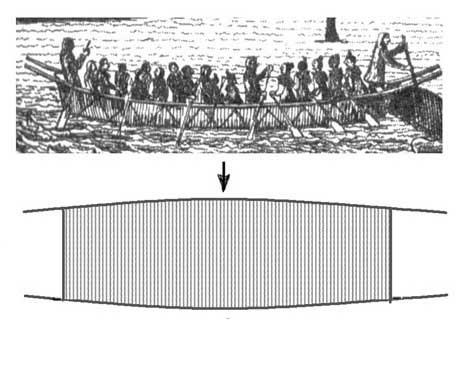

Significant to

our quest for an answer to the "longhouse foundations" is the

appearance of the Greenland "Eskimo" skin boats. They have poles

on the ends, that may have been intended for handling the boat, and

there is a crosscrossing of rope on the side, which suggests the

skins are designed to be easily removed. Compare these Greenland skin

boats with an illustration of the Alaskan version. The Alaskan

umiak looks like a more permanent construction.

Detail from 18th century illustration of Greenland Inuit whaling

showing the sides made of two long poles, probably with skins attached.

In addition there appears to be ropes suggesting the skin was

easily removed by "unlacing". This suggests that the skin was easily

removed to be used for the purposes of creating a shelter

By contrast, the Alaskan skin boat, looks quite permanent. It lacks

features suggesting a desire to easily handle the boat and remove the

skin. Various parts of the skin may be affixed directly to

the frame here and there by pieces of rope though the skin, in contrast

to the Greenland scheme of holding the skin by pressure of the "lacing"

on the outside.

The illustration of the Greenland

"Eskimos" shows a gathering of the clans (bands, extended families) of

the sea-going tribe. Each large umiak would represent one clan, and it

appears there are four clans, which is a typical number for a natural

tribe. Among boat-using hunting people across the northern world,

a tribe would consist of some four to six clans who had

established over many generations, claims or rights to specific

hunting territories, rights which they would pass down from the clan

chief to male descendants.

THE

WAY OF LIFE OF ABORIGINALS

The manner in which clans unite to

form tribes is influenced by their circumstances. In a forest setting,

the clans might unify into a tribe if the clans each occupy a branch of

a river system. In the case of ocean-people, the pattern of ocean

currents, coasts, and winds could join a number of clans into a tribe.

The hunting territory for the seagoing peoples was

not defined in terms of land area as in civilization (based on farming

people) but in terms of specific hunting areas in the sea. The

clan would move within their own territory, from one hunting area to

another according to the patterns of nature, in a usually annual

circuit, only coming back to the same place the following

year. Each clan would defend their

territory, and respect the territories of the other clans. There

would have to be an agreement if more than one clan hunted at one

location. They moved through the environment on their own, but

congregated, usually annually, at an agreed-apon location, to

affirm their identity in the larger social order, the tribe, exchange

news, pursue celebrations, find mates. A good place for the

multi-clan meeting was where food was plentiful enough to support all

the clans together, and where it was advantageous to have help from

each other, such as hunting whales.

Each clan had their own territory, their own

number of campsites that they visited year-by-year, and they would have

guarded their rights to the animals. It is because hunting

territories, campsites, associated clans, etc were all strongly

defined, that a clan was not likely to wander aimlessly. Strange

territory meant they could be intruding on some other people's

territory and had to be on guard, proceed with caution.

It is

because of this ownership of hunting areas, that it would be difficult

for any foreigners to intrude. Any Europeans attempting to

harvest some

animal like walrus from a location a clan owned, could end up being

attacked by the entire tribe - other clans coming to the aid of the

clan experiencing trespassing. While it would not have been

difficult in recent history when Europeans had guns , early Europeans

would not have had much defence against the aboriginals if they

intruded on the aboriginal hunting territory. Any "Albans" at

well known walrus hunting sites would have been driven off It was

far easier to remain respectful and detatched towards the natives, and

get the ivory by trading some quaint European items - cloth, metal,

trinkets.

Thus the archeological features discussed by Mowat,

the seeming longhouse foundations and the beacons visible from

the sea, are much more easily explained in terms of long established

native sea-going

people of the northwest Atlantic, who spent most of their lives moving

around on the open Atlantic and harvesting large sea-animals like

whales. They would have been ancestral to the Greenland "Eskimos" and

originally archeologically "Dorset". These people would have

systemantically visited

familiar campsites year after year, in their annual

circuit, camped on rocky coasts and islands if it was needed, to

be close to their hunting places, and used methods and equipment that

had been adapted to this specialized form of life over countless

generations. With a way of life spent mostly on windblown rocky

islands, being able to use the skins of one's boats as shelter would

certainly have been part of a good system.

The boats shown in the

illustration were clearly not invented overnight, but over centuries in

adapting to the special conditions encountered in the seas off the

coasts of Greenland and Labrador.

The places where the sea animals were located were

usually far from the coast, among scattered rocky outcrop; and

so, the sea-harvesting clans needed to be able to improvise

their life on even small rocky islands not far from the hunting sites.

They would improvise shelters from very large skins that were easily

removed from frames with the long poles, by "unlacing" the rope. The

debated "longhouse foundations" may simply have been one form of

shelter, designed for open flat terrain. Elsewhere they draped the

skins against rock walls, in front of caves, etc.

HOW

SHELTERS MADE

Merely overturning umiaks produced cramped shelters.

Using skins of boats rather than whole boats gave greater

versatility and comfort in fashioning shelter. It solves the

objection of the umiak being too narrow if overturned. Possibly two

skins could be combined to create a large communal shelter for two

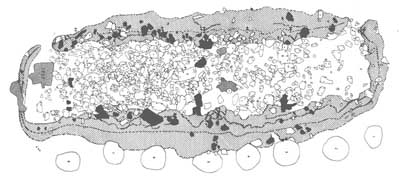

clans. Below reproduces, from

Farfarers one of

the remains of the

so-called "longhouse foundations". Note that the scattered rocks do not

show a constructed wall; and that assumptions that there was one, is

speculation. The nature of the edges, with rotten turf and stones,

could merely represent the accumulation of rocks and turf used to hold

down and seal the edges of the tent through repeated use.

Pamiok Longhouse No. 2 site after reproduction page 8 of The

Farfarers:Before the Norse, Mowat, Toronto, 1998 (The black

rocks are thought to be in their original positions)

The archeologist of the site, Tom Lee,

interpreted the distribution of rocks and turf as a broken turf and

rock wall, and used the loose rocks to build a speculative

reconstruction which is shown in

Farfarers page

7. If the skin

boat comes apart easily, if the skins can be easily removed by several

men via the poles, and if the poles themselves become supports, then we

have all the ingredients for shelter. A shelter and an umiak

cannot exist at the same time. And that is what is suggested in the

illustration - the boats appear to contain everybody (other than those

placed temporarily on rock islands) - men, women, children.

The shelter, the longhouse, may

have been made out of two umiak skins, connected to two poles each. The

base would then be held down by rocks and turf - which would explain

why nowhere have archeologists found proper walls, only loose stones

and turf. The following speculates on what was done. It requires

further research by people with more information about the traditional

Greenland umiak.

Conception of he Pamiok No. 2 site with a tent made

using 2 umiak skins including the poles that formed the skin boat

sides..

One would expect that the interior would

have had arrangements of stones for fireplaces, sleeping platforms,

etc. In my interpretation, shown in the illustration, most

of the interior stones actually belong in the interior, and the fewer

stones around the edges were never used as a wall, but simply piled on

the edges of the tent to hold down the edges. Turf pieces sealed the

cracks. Repeated use meant the site's edges always looked broken down

since they were never built up.

Who made them? Were they made by seagoing

aboriginals? Mowat records archeologist Tom Lee

saying

"I've found little in the way

of artifacts except a lot of

Dorset-culture litharge [scraps and flakes of flint] . . .Dorsets

appear to have camped here after this longhouse was abandoned."

Lee assumes the site was abandoned,

because he preconcieves a wall.

But

if there never was a wall, and it was a tent-site re-used over and over

by the Dorset people who left only their food scraps behind, then it

would agree with the concept that it was made by seagoing Dorset people

who came with a large umiak, or two per clan, pulled them ashore,

removed the skins, and erected the longhouse tent using the skins. When

they left they took everything except scraps away with them.

There never was a proper wall

The large number of such "longhouse sites" in the region

of Ungava Bay suggests it was a

congregating area for clans.

Indeed a

major hunting site was nearby. As mentioned above, while clans moved

through the environment independently, they congregated at special

locations of abundance and activity of larger scope that many clans

could better perform together. All the nomadic hunting peoples

travelled around in small extended families and then congregated at

bountiful sites where food was plenty and/or a combined effort was

reguired involving many clans - as we see above in the illustration of

Greenland aboriginal whaling. It is easy to imagine a gathering of

clans near walrus hunting grounds and hunting in a group effort for

greater efficiency.

The Cylindrical Beacons - Seemingly

Used Around the Entire North

Atlantic

Typical cylindrical pillar of rocks often over 6 ft (2 m)

tall that are best explained as markers of campsites in the annual

circuit of movement of the seagoing Dorset clans, to be seen from the

sea.

Mowat's map of the

cylindrical beacons in the Canadian arctic shows them widely

distributed on the Canadian east and arctic coast. The wide

distribution of these "beacons" -- in Ungava Bay, Hudson Strait,

eastern Hudson Bay, down the Labrador coast, etc --

cannot be

explained by occasional cross-Altantic visits by Europeans (ie

"Albans"

or Norse). They were obviously established by sea-going aboriginals of

many clans, and over many generations. They could be very old. Once

made, there was no reason to remove them. They became permanent

landmarks.

These beacons were not made by the recent

Inuit peoples, who instead erected irregular stone structures called

inuksuak made from a few

large rocks to depict a person and to signify that a human had been

there. The beacons were visible from the sea and clearly were made by

seagoing

peoples. With respect to a beacon found near the Pamiok No. 2 location,

Mowat quoted archeologist Lee as saying ".

. too big, Too

regular. Too well made. Not Eskimoan at all. And look at the thickness

of the lichen growth on them. They're too old to belong to the historic

period."

But something that is old, that predates the

newer culture, would belong to the earlier "Dorset" culture,

would it not?

Mowat continued: (p 162) "

Tower beacons

of this type are also found on Britain's Northern and Western

Isles, Iceland, western Greenland, the eastern Canadian high

arctic, the Atlantic coast of Labrador, and Newfoundland."

I add

that other sources say they can be found on the Norwegian coast

too. This means that the beacons were not merely North American

but a North Atlantic skin-boat

sea-hunter institution, as typical and widespread as the Atlantic

seagoing skin

boat itself.

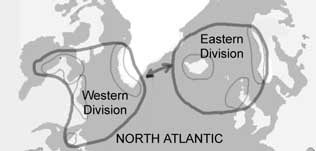

Note on the following map that all these locations

mentioned by Mowat, plus Norway, circle the North Atlantic.

It suggests two divisions of North Atlanic seagoing aboriginal peoples,

eastern and western. I have defined these divisions acording to the

absence of islands between Iceland and Labrador and by the patterns of

the ocean currents. Mowat may want to view the makers of these beacons

as a relatively civilized seafaring people, but the truth may be that

they were largely primitive (in the sense that they were nomadic, and

lived off the sea in a self-sufficient manner), and all belonging to

the same race as the Greenland Eskimos. It is European chauvinism that

wants these people to be more like the modern seafarer of the Northern

British Isles, rather than the Eskimo/Inuit.

There is a general tendency of older generations to

dismiss aboriginal peoples, make them background decorations to the

adventures of Europeans; and as sympathetic as Mowat may be to

aboriginals, he was raised to celebrate the Norse, the British, the

European and place aboriginal peoples in a different universe.

The "beacons" are found throughout the North Atlantic (areas in the

lighter lines), and it is clear they were made by ancient

skin-boat-using aboriginal sea-harvesters of the North Atlantic, who

comrpised two divisions (heavier lines). The eastern division has

long vanished, while the western division was last represented by the

Greenland whale hunters.

A map of the currents of the North Atlantic shows why there would

have been a natural division between eastern and western tribes. The

circling of the currents encourages one division to be set up mainly

around circuit B, and the the other in circuit C. In addition note that

the space betwen Iceland and Labrador, without islands, would discourge

travel between the two divisions, except along the coast of Greenland.

This current along Greenland , travelling east to west would

encourage peoples from B, with evolving European racial

features , to venture towards the west. The names "Dorset",

"Fosna" and "Komsa" refer to archeological designations of prehistoric

cultures in these areas, their artifacts seen along the coasts and

islands. I propose they were all related and ultimately has the same

origins.

These beacons, placed to be

visible from the sea, thus marked the locations of campsites for the

nomadic sea-going aboriginals of the North Atlantic. Once an ideal

campsite location was established, it would be reused over and

over, year after year, and thus it was useful to construct

beacons visible from the sea, in order to find the place again and

again.

Conclusions

Mowat's

The

Farfarers:Before the Norse, (Mowat, Toronto, 1998 )

presents much good information from his research, but his

analysis is not scholarly. He began with an idea of peoples from his

Scottish heritage riding in skin boats and using the boats as shelters,

and basically did what all bad scholars do - organize and select data

in order to 'prove' a preconcieved idea, and resist abandoning it when

the research did not really support the idea as he originally, naively,

concieved it.

Proper scholarship only entertains a general

question and tries not to predict the solution. The question is "How

were the longhouses suggested in the archeological finds made, and who

made them?" He may have originally thought the Norse made them, thus he

did change course once before beginning the book in his imagining an

earlier people, he decided to call "Albans". But the research really

did not support such a simple, narrow, interpretation. But could he

back out now? His publisher was waiting for a book!

There is a good story for "Albans" of Roman times,

including their possibly being the origins of Beothuks, but for the

centuries after the Roman Age, there is less and less basis for

contacts with North America by a single group. More likely the North

American evidence represents footprints made by a number of groups,

from traders who kept their journeys secret and established a couple of

trading posts, to groups of monks creating a settlement on

Newfoundland, to early settlers who were not Norse, but Finnic (the

original north European boat people), to random accidental visits by

lost Icelandic fishermen. The reality behind the diverse information he

collected from his research is far more complex than his simplistic

theory about a hypothetical "Alban" people.

He may have sensed alternative paths for the book, but was

forced to continue on the "Alban" path, and thus created something that

is more fantasy than fact, and has been treated that way.

I believe there are three major stories in the accumulated

evidence - the story of Roman Age native British, the story of North

Atlantic seagoing aboriginal peoples, and the story of contact by

northern traders, not even mentioned by Mowat. And within these three

themes there are many subdivisions, both on the British side and North

American side. For example the evidence of a settlement may represent a

trading post set up by traders. The texts speaking of a settlement of

clergy may represent a genuine settlement of Irish monks, that if they

were all men, only lasted one generation. There are several major

themes each with several angles, and it may be very difficult to find

connections between the many possible themes and angles.

2016 (c) A. Pääbo. UPDATED 2016

So

is it possible the Beothuks were the "Albans" who hunted walrus and

created the "longhouse foundations"? We note that humans are by nature

very territorial, so that Beothuks could not trespass on hunting

territory already occupied by indigenous "Dorset" culture seafarers.

That may be the reason they ended up in Newfoundland, south of the

Labrador coast and the "Dorset" peoples. We note that since the Dorset

culture sea people did not sail, but went with currents, it is possible

that they avoided travelling south past Newfoundland, on account

currents would drive them out into the open sea. By staying adequately

towards the north, if swept to sea, they would be carried back to

Greenland. See the map below showing the current circuit "C".

So

is it possible the Beothuks were the "Albans" who hunted walrus and

created the "longhouse foundations"? We note that humans are by nature

very territorial, so that Beothuks could not trespass on hunting

territory already occupied by indigenous "Dorset" culture seafarers.

That may be the reason they ended up in Newfoundland, south of the

Labrador coast and the "Dorset" peoples. We note that since the Dorset

culture sea people did not sail, but went with currents, it is possible

that they avoided travelling south past Newfoundland, on account

currents would drive them out into the open sea. By staying adequately

towards the north, if swept to sea, they would be carried back to

Greenland. See the map below showing the current circuit "C".