2. THE

OCEANIC BRANCH

SEA-GOING SKIN BOATS AND OCEANIC EXPANSION:

The Voyages of the Whale Hunters

by

ANDRES PÄÄBO

Synopsis: In the far north, where trees were small,

it was only possible to make small one-person dugouts (like the Khanti

still have). The "Kunda" culture of the Baltic, which - as determined

from the large

harpoons that have been found - hunted in the sea, was able to make

large seaworthy dugouts as their north-south seasonal migrations in the

east

Baltic, allowed them to find the required large trees needed. But when

some of them moved north towards the White and Arctic Seas, only small

dugouts were possible and seaworthy vessels with high walls had to be

made in another way. The skin boat I believe developed in the arctic

where the established traditional dugout could not be made large enough

for use in the open sea.. My theory is that the inspiration for the

boat made of skin on a frame began when someone mistakened a swimming

moose for a floating log, and that inspired an attempt to make a moose

carcass into a boat. That introduced the principle of using ribs to

hold the skin. Over time the priniciple was refined and large boats

were developed from sewing skins together; but the source of the skins

continued to be honoured by the moosehead (now possibly carved) on the

prow. These new large skin boats could be used to hunt whales,

and rock carvings near the White Sea and Lake Onega are testimony to

whale hunting about 6000 years ago. Interestingly the Greenland

Inuit appear to have been hunting whales from their large skin

boats - although now made of different skins - not long ago, as shown

in an illustration in an 18th century book. Whale hunters,

lacking any fear of the open water, and accustomed to travelling long

distances and even following whales, were the instrument for the

expansion of boat peoples by sea beyond their origins in northern

Europe. The currents of the North Atlantic suggest the North

Atlantic was crossed easily and the "Dorset" culture became established

when a tribe became established in the current routes of the sea east

of Labrador. The connection between Finnic languages of the

region south of the White Sea, and any other people with whaling in

their traditions, can be seen in language comparisons. Although not

close enough to permit comparative linguistic analysis, comparing the

Inuit language with Estonian/Finnish presents similarlities in many

fundamental words . But skin boats ventured south as well, and produced

such crafts as the birch bark canoe (skin boat using birch bark as

skin), and the Pictish skin boat later made of ox hides when the walrus

of the northern British Isles were extinct. They also circled the

arctic waters (a relatively small distance if you view it on an actual

globe and not on a map that stretches the north and south regions.) and

descended down Pacific coasts as well.

Introduction : From Dugouts to Skin Boats

WHEN INVENTIONS COME INTO USE

The theory of the expansion of Boat Peoples from the

watery lands south of the Ice Age glaciers ( THE ORIGINS AND EXPANSIONS

OF BOAT-ORIENTED WAYS OF LIFE : Basic Introduction to the Theory

), proposes that the first boats arose from logs developed to hold

people - the dugout canoe. Archeologists have not found very many

canoes since most have rotted away. But a few have been found

from Britain to the east Baltic -

or parts of them - preserved in bogs. But, archeologically

speaking, the greatest testimony to

the originating and expanding of a dugout boat people are adzes. Stone

adzes have been found from Britain to the Urals, suggesting a

successful culture developed in the vicinity of Denmark (where

archeologists found the first evidence of it in the "Maglemose"

culture, found in a Danish bog).

Unfortunately archeologists and other scholars have

failed to adequately appreciate what great development took place when

a prehistoric people developed a new way of life involving dugouts

boats/canoes. They assume that any people anywhere can

decide to build a boat and suddenly create a way of life involving them.

Even our modern

experience can tell this is not true. Who today can build a sleek

dugout without actually having a master show us or at least a

complete set of instructions. Those who have attempted without

instruction and from only the concept, can

only manage a crude trenched log. But even before ANYONE had created a

dugout, how would an inventor even know what was needed? If humans have

never before glided in a water vehicle, how would they know that this

would be useful? How would they know that this new method of getting

around will give them greater success than the original method of

creating paths and walking?

It is important to bear in mind that if

some invention is not yet in use, it cannot come into use

immediately just because a human can think of it.

Human ingenuity can

invent something to solve an immediate task, and even invent something

exotic for entertainment, but inventions that shape an entire way of

life take a long time to evolve. A good example today is the

automobile. The automobile could not have come into existence, had it

not been for precedents in earlier vehicles drawn by horses. The

automobile simply replaced the horse with an engine.

Before that,

even the use of a horse to pull wagons and carriages took a long time

to develop. Even though

humans were entertaining themselves by jumping on the backs of horses

for sport from the moment they investigated the animals, it probably

took 1000 years for conditions to push societies to develop the horse

into the fabric of society. Similarly other beasts of burden like oxen,

also took some time to become adopted into practical uses. Ironically,

North

America certainly had animals that could have been similarly

domesticated - bison domesticated to pull wagons, or the riding of a

large animal like a moose - but it never developed. And yet, within a

couple of generations after the Plains Indians saw the Spaniards riding

horses, they were suddenly riding horses. WHile it takes a long time

for a new innovation and its integrated use in a society to

develop, once it has reached maturity then other people can immediately

adopt it. The motivation to do so is only partly its practical benefit,

but because humans are social creatures and will imiate anything that

seems popular and valuable in another society.(We need only note how

fast the cellphone has been established in the modern world, including

third world countries where the cellphone users are still living in

shacks.)

Thus, an automobile could

not have developed without the

conditions created in the Victorian era, of cities in which everyone

moved from place to place in horse-drawn buggies, wagons, and

carriages - institiutions centuries in the making. But after the

automobile was invented, every nation in the

world could now imitate it, and even manufacture automobiles and become

the

world leaders, overtaking even the nations in which the automobiles

came into first use.

Thus, applying the theory to the

evolution of a boat-oriented way of life: obviously humans had always

been able to create boat-like toys from floating bowls in water, and

even creating huge boat-like bowls and having a child play around with

it in water games. Obviously too whenever ancient tribes found their

way blocked by a river or a lake, they were intelligent enough to put

together some sort of raft to cross it. The issue is not in human

ingenuity. The issue is in the development of an entire way of life

revolving around transportation and hunting using a boat, instead of

the traditional ways travelling on foot. If it had never existed

before; if humans have previously only hunted and travelled on foot;

then doing these things with a boat required a major evolution, perhaps

as elaborate as our long evolution today towards the automobile,

starting with the horsedrawn wagon, nay-- starting with harnessing the

power of a horse!.

The development of a boat-using

way of life thus had to go through many trial and error developments,

and human need and circumstances judged which choices were better and

which were worse

(Tribes that adopted the better ways were more successful, had more

children, and also found rival tribes copying their methods.

Evolution itself selected the good choices!)

THE

NEED FOR PRECEDENTS

One interesting observation

about

inventions that are not toys but become part of the way of life of a

human society, is that every new development needs to be founded on an

old one, because too dramatic a development throws the operation of

that way of life into chaos.. Early automobilies for example had to be

built on top of the existing institutions of the

horse-and-carriage, The first automobiles had to still look like

carriages, except powered by engines not horses. That would not disrupt

society's operation (other than putting liveries out of work, but then,

the liveries turned into automobile repair facilities.) It is clear

that change cannot be dramatic. If someone had

produced an automobile that looked like a modern automobile right away,

the public would not have been able to relate to it. But the "horseless

carriage" was wonderful. It was still the familiar carriage, but it did

not need a horse to pull it.

The evolution of the boat had to proceed in a

similar way. It had to slightly improve something already established.

If someone produced the skin-covered frame boat right away, people

would not have been able to understand it. A new development

could not be dramatic. Real developments in society proceed

slowly, step by step.

I have already discussed in the main article THE ORIGINS AND EXPANSIONS

OF BOAT-ORIENTED WAYS OF LIFE : Basic Introduction to the Theory)

how since a way of life on the water is so foreign to human nature it

required a long period of pressures for it to develop. The

circumstances which caused the development were all there in the late

Ice Age, when the climate was warming and the meltwater from the

glacier flooded the lands formerly holding reindeer herds on a frozen

tundra in the North European Plain.

It is easy to imagine that the stranded reindeer

hunters, no longer able to hunt reindeer, turned first to other large

animals such as the moose - a large animal that is comfortable in

marshes. It is interesting that Estonian uses the word põder for the moose while FInns use

the parallel word poro

for reindeer. This suggests that where the reindeer

disappeared, the word for reindeer was transferred to the moose, but

where both the reindeer and the moose were found, the noose could not

acquire the word for reindeer. In Finnish, the word for 'moose' (in

Britain 'elk') is hirvi.

In hunting the moose and other large animals, the

early hunters (about 10,000 years ago) would encounter rivers and

marshes, and had to improvise rafts to get across. Perhaps they

straddled a log and paddled across on it.

After a time, someone decided to paddle across while

trying to keep their feet out of the water. Why not make a cavity in

the log?

Once there was a cavity in the log, the hunter

gained the ability to go after water animals directly from the crude

boat. For example fishing or hunting wildfowl, not to mention

collecting edible water plants, was now easy.

The canoe, thus fostered a change towards hunting

and collecting foods connected to the flooded lands - and if the lands

were mostly flooded, it would have been teeming with water plants and

animals! In turn, changes to the dugout boat, and its use,

altered the way of life as well.

Then the hole was made more

comfortable, and larger, to hold more than one man. Then someone

discovered that making the outside more streamlined allowed it to

travel faster.

Each change was then tested in actual practice. The clans and tribes

that had the better developments in both the vehicle and its use, had

more children than those who has made poorer developments. Thus it was

evolution itself that decided, from greater success and population

growth, that developments would constantly move in the more beneficial

directions.

Eventually the log turned into a dugout with a

streamlined shape and thin walls (to be light enought to carry). Such

sleek dugouts are still made and used by the Khanti of the Ob River in

Siberia, althought they can only make small single-man versions on

account there are no large trees in their northern environment.

The Khanti method of making the dugout is probably thousands of years

old. The method involved using fire to make the cavity. The stone adze

was not used to chop the wood, but to chop away coals in the direction

in which the maker wanted the fire to proceed. Fire is halted when

there is a buildup of coals. In the 1980's filmmaker Lennart Meri

documented the making of a dugout in a Khanti campsite on a branch of

the Ob River. The Khanti dugout, used by one man in the fashion of a

kayak, was limited in size by the limits in the size of trees in their

northern location.

The first dugouts, those

associated with the archeological "Maglemose" culture, were designed

for dealing with the marshy landscape from the region now the Jutland

Peninsula and southern Sweden, east along the south Baltic coast (the

Oder River basin) to the southeast Baltic. These people had no need nor

desire to venture out into the waves of the Baltic. Humans did not

develop in uncomfortable directions unless circumstances forced them,

or circumstances benefited them beyond their sense of discomfort.

"Maglemose"

to "Kunda" Culture: From Marshes to Seas

Archeologist Richard Indreko discovered in the early

1900's on a hill (that was originally an island) at Kunda in northeast

Estonia, evidence of a campsite of boat peoples who were obviously

venturing out into the open sea. We know they were dugout users,

because archeologists found large adzes. But their large harpoons

clearly suggested they were hunting large sea animals like seals or

small whales.

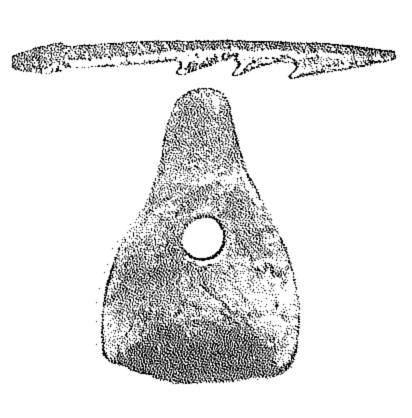

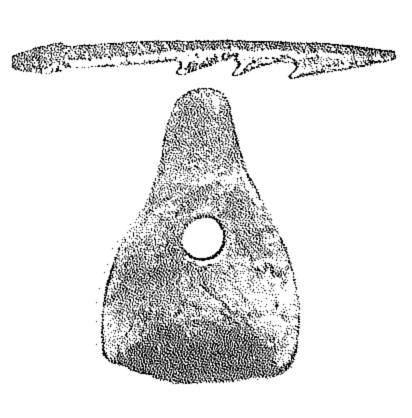

From the "Kunda"

archeological finds, the image at right shows a large harpoon and an

adze head -used for hollowing a log for a dugout with the help of fire.

To hunt seals and larger sea animals required

venturing out into the waves of the sea, and that required larger

dugouts with high prows. These people had to look for the largest

trees they could find - giant trees a meter or more in

diameter. In Estonia in the last centuries, large oaks are

celebrated. They had names. I think the tradition of celebrating oaks

began millenia ago, when a tribe would identify oaks that looked like

they had potential of becoming very large, and suitable for making into

a large dugout. Since such a tree takes a many generations to grow to

the appropriate size, it was necessary for a tribe to designate a tree

for making into a dugout already many generations ahead of time. As the

world turned towards making boats with planks, the purpose of reverence

for trees destined for large dugouts was forgotten.

But why did the "Maglemose" culture become seagoing

when it expanded up the east Baltic coast. I think it is because of the

prevailing winds. The winds came from the northwest, and large

waves were always crashing onto the east Baltic coasts. While boats

could find calm in the less of islands, when they crossed waters

roughened by the forces of the prevailing wind, the going was rough. It

was natural for the people to make larger and larger dugouts. At the

same time crashing waves tended to produce barren rock islands out in

the sea which could have been the resting places of herds of seals.

Perhaps there were beluga whales as well.

Thus the "Kunda" culture was fostered by a

combination of the attraction of the large sea mammals, and necessity

of dealing with prevailing winds. These people probably travelled

up and down the coastal water, camping on islands.

The "Kunda" seagoing dugout of about 6000BC,

was a successful one, and its users no doubt expanded into Lake Lagoda

and Lake Onega too. The land was still depressed from the former weight

of the glaciers, and it was probably possible to ride a boat from

the Baltic Sea area to the White Sea.

It is easy to imagine that once the large dugouts

had developed, with population growth, the "Kunda" culture tribe broke

apart from time to time, with a portion leaving the parental

territories in search of new territories of a similar nature in the sea

environment.

Archeology has found the remains of a large dugout

in the Jutland Penisula area. This dugout had a place for a torch and

is thought to have been used to harvest eels at night. We cannot tell

if the eel hunters came from the "Kunda" culture, or developed

independently out of the "Maglemose" culture, similarly drawn out into

the sea by opportunities.

Eventually large dugouts were common in the Baltic

Sea. Archeological finds suggest that the standard large dugout

of the east Baltic was large enough for three pairs of rowers and one

helmsman, totalling seven men. If the boat had to carry cargo, the

cargo was placed in the middle, and two rowers were removed, leaving

five. It is interesting that Estonian and Finnish remembers this in

their numerals. (Using the Estonian version) the word for 7 is seitse, but that resonates

with sõiduse 'of the

riding, voyaging' and 5 is viis,

which resonates with viise

'of the carrying'. Because both Estonian and Finnish have it, this must

be millenia old.

The breakaways from the "Kunda" culture had to

travel to find new territories with the same sea animals. The

seas were higher than they are now (or rather the lands were lower, not

having rebounded yet from the pressure of the Ice Age glaciers.) and

the Gulf of Finland, Lake Lagoda, Lake Onega, and even White Sea were

interconnected.

We do not know where the sea-hunters went, as it is

difficult to find the traces of highly mobile boat peoples in lands

that were mostly islands in a flooded landscape. The best

evidence comes from carvings made on rocks at Lake Onega, the White

Sea, and in places across arctic Scandinavia.

These migrating tribes had no problem finding the

sea animals. The real problem was in finding trees large enough for

seagoing dugouts. The further north they went the smaller the trees

were. Like today's Khanti. they could only make small single person

dugouts. Either they had to make long journeys southward to find large

trees to make new dugouts as the old ones degenerated, or they had to

find a new way to make boats large enough to handle the waves of the

open sea.

I believe the solution was found in what I would

call the "dugout moose".

Moose are large animals that can cross large bodies

of water, and will do so as long as they can see the opposite side. A

swimming moose would seem like a very large moving log. I believe it

inspired the idea of using a moose carcass to make a boat.

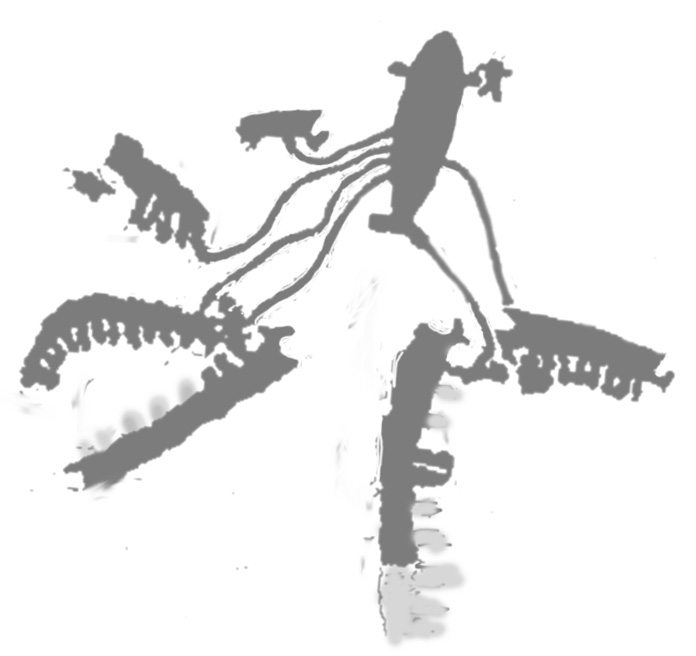

The rock carvings of Lake Onega, north

to the White Sea, and across the European arctic to the coasts of

arctic Norway show a very interesting boat. The simplest and smallest

one shows a moosehead on its prow, and it holds no more than three men.

When comparing the scale of people versus the size of the head on the

prow, it is clear that what they have done is in fact created a "dugout

moose". They have taken a moose carcass, slit it open along its back,

and removed everything other than the skeleton. To retain its shape,

they have simply used

the same principle as the moose itself has to hold its shape -

ribs. It is possible that the earliest and simplest "dugout moose"

retained the moose's own ribcage. I can easily see them using the

moose's own skeleton - adding wood pieces to give it an appropriate

shape. Then using fire - just

like in the creation of a dugout - to dry and preserve the inside. The

final result is a boat which is a dugout moose mummified and hardened

by drying with fire. The resulting boat offered a very high prow

that could handle high waves.

This, I believe, was the beginning of all the

subsequent boats that have ever been built - up to the oceanliners of

modern day - based on the principle of putting a skin on a frame. The

greatest oceanliner on earth starts 6000 years ago with a moose

swimming across a lake and being initially mistakened for a floating

log!!!!

The "dugout moose" was just the beginning. As the

rock carvings also show, pieces of skin

could be sewn together, and more frame added, in order to create a long

boat capable of holding 20-50 people. See the story of the

development of the skin boat from dugout precedents in the below

information box.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE

SKIN BOAT FROM THE

"DUGOUT MOOSE"

Theory by Andres Paabo

OB RIVER

The concept of the original boat did not involve

frames and skins.

All boats were dugout logs. The dugout is still made by

the Khanti of

the Ob (image at right is from a Lennart Meri film produced in Estonia

in the 80's) However this dugout is small because at the northern edge

of the forest zone, the trees are too small to make large seaworthy

dugouts.

ARCTIC NORWAY

A small dugout like the one of the Khanti is seen in the

top image

in the rock carving from arctic Norway, dated to some 6000 years ago.

But this small dugout was not adequate for dealing with the high waves

of the ocean, The image below it show the skin boat made from moose

hide, the moose head represented on the prow.

ALGONQUIAN ROCK PAINTING

It

is interesting that the single person dugout is

also seen in Canadian rock carvings (image to left from book by

Dewdney), helping argue that the people who crossed the

Atlantic with skin boats retained knowledge of creating the small

river-dugout. While some may say that the image shown to the left is

a birchbark canoe, I disagree. Dugouts were very slim because

it was not possible to build up the sides . Birchbark canoes actually

were derived from skin boats. They were skin boats using birchbark skin

instead of animal

skin.

Boat people who wanted to harvest the arctic,

therefore could not use

the slim dugouts made from the small northern trees. They had to

develop something new. My theory is that it began with someone's idea

of trying to make a dugout from a dead moose carcass.

LAKE ONEGA ROCK CARVINGS

The

Lake Onega rock carvings present several examples showing the

small

moose skin boat being used in sea-hunting. Allowing for some

variation by the artist, the scale of the moose head is

generally of natural size, when compared with the size of the two or

three people inside.

THE MOOSE AS A BOAT

All

the

skin-on-frame boats of the world owe their origins to this

beginning, which I believe began with applying the concept of the

dugout to a moose carcass. The idea may have begun with someone seeing

a moose swimming and initially thinking it was a large floating log.

Coming close they discover it is a moose; however the idea of making a

large boat was already planted in their mind and they wondered if a

boat could be made from it. In the beginning the idea of a skin on a

frame did not exist. It was born when the concept of the moose's ribs

was employed to hold the skin in shape.

Note that the

moose has a massive body giving a great deal of skin that can

be

stretched to create a boat large enough to hold three men.

Since the moose (shown above) is a forest

zone animal, the use of the moose meant that its users did not remain

in the arctic, but migrated between the arctic coast and forested

regions. It is interesting that the Lake Onega carvings show

no images of moose with antlers. Since males grow antlers in summer and

shed them in fall, it follows that the Lake Onega people were in the

Lake Onega area only in winter-spring. They then left for the arctic,

perhaps going as far as Alta, and did not experience the moose with

antlers. The Alta rock carvings also show boats with reindeer heads. It

suggests that those people who DID stay in the arctic, and did not

return south, used the reindeer as a substitute, sewing many skins

together. (See SOUTHWARD

MIGRATIONS OF CIRCUMPOLAR SKIN BOAT PEOPLES: Looking at Picts,

Algonquians, amd Pacific Coast tribes for more on the Alta rock

carvings of northern Norway)

The next step was of course the enlarging of this

boat, to hold many

more people. The obvious way to enlarge it was to simply sew skins

together and make it longer. The following images compares a rock

carving of a large boat at Lake Onega, with a typical UMIAK of the

Alaskan Inuit. The umiak shown was made of walrus skins, but it gives

an idea of size. Walrus skin was discovered to be a better

skin than reindeer skim, for those peoples who stayed in the arctic and

did

not descend south in winter to the forested regions where moose were

found.

Rock Carvings Showing Whale Hunting in

the White Sea as Early as 5000-6000 Years Ago

THE

DEVELOPMENT OF WHALING

The skin boat was designed to deal with the

high waves of the open sea. By lengthening the boat it could hold more

people, and a large boat with many people was needed to catch the

ultimate of sea creatures - the whale.

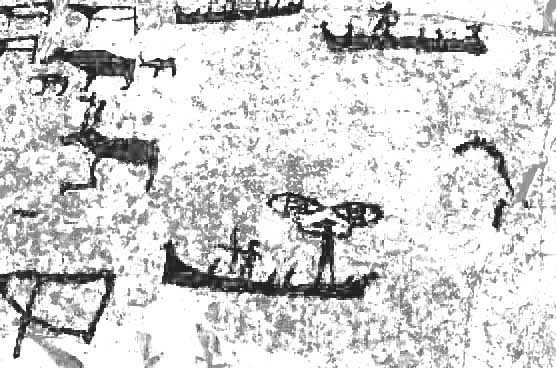

The

Lake Onega large boat, obviously made of skins on a frame. The moose

head, perhaps now carved of wood instead of a mummified real head is

seen at the front. At the front of this image we see what is

pobably a seal.

The arctic boat people who developed whale

hunting, not only created large boats, but their quest for whales took

them far into the sea, as they searched for whales. Only those sea

people willing to take on whales

would ride the open sea as boldly as the whales themselves. These

people would have travelled from the White Sea region, both eastward

and westward along the arctic coasts. They would have found whales

congregating at Greenland, and travelling up and down the east coast of

North America. There were whales, seals, and walrus as well to be found

in arctic North America. If these people reached the Pacific, they

would also have found whales, and come south along both Pacific coasts.

There is no question that

highly developed methods of whale hunting existed as early as 5000-6000

years ago, because they are shown in carvings dated to about that time.

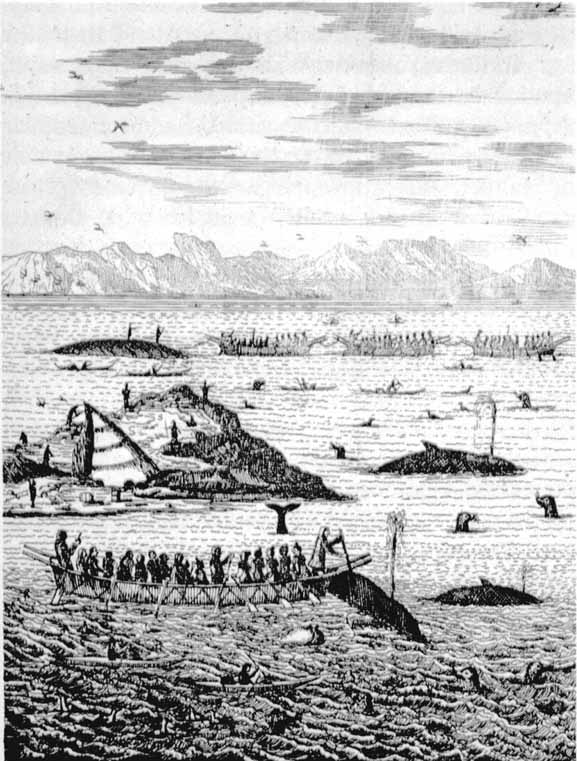

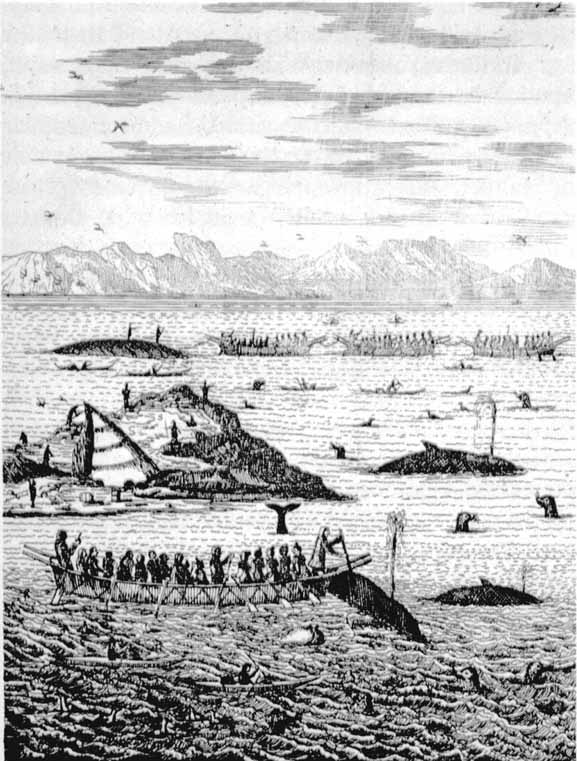

The most amazing rock picture is the one shown below (presented here

intepreted in black and white, with the whale hunting event set appart

from other elements around it for clarity.)

Whale

hunting from moose-skin

boats, probably on the White Sea (in today's arctic Russia,

north of Lake Onega). This image is developed from reproductions from

rock carvings that have been dated to between 5000-6000 years ago.

(Light grey restores missing, worn, sections)

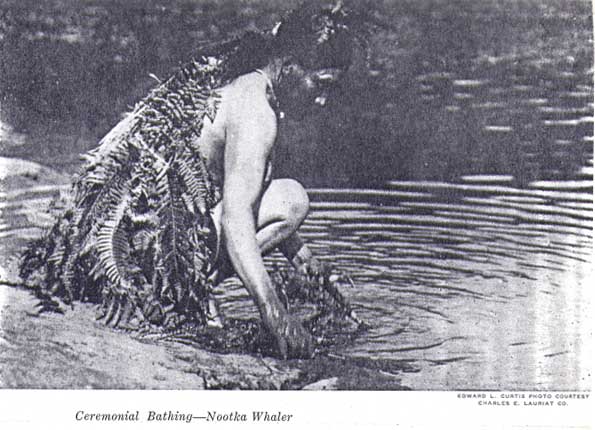

The above illustration is very surprising, because

it first of all proves that the large boat shown in the Lake Onega rock

carvings is not some kind of fantasy boat, as early archeologists said.

It really existed. This illustration does not show anything imaginary.

It shows the same activity as witnessed in the 18th century and

recorded in the following illustration. Note especially the small boats

accompanyng the large one. Apparently when the whale was entrapped, an

individual in a small boat would go to the eye of the whale and speak

to it, gain approval and willingness to give up its life.

There is no question that the Greenland Inuit continued a practice that

began some 5000-6000 years earlier, probably at the White Sea with

earlier precedents with smaller whales perhaps in the "Kunda" culture.

(How else would you explain the large harpoons of the "Kunda" culture?)

The Illustration of the Greenland Inuit shows only one large boat in

the foreground, but I think that is purely artistic liberty. The artist

sought to show everything in one image. The important part of the

illustration is that there are three large boats in the background, a

total of four boats. Each boat probably represents a clan. A tribe

consisted of several clans. For most of the year, each clan travelled

by themselves in their own territories, but the clans came together

once a year to carry out activities that were better done collectively.

It happens that whales congregate off the shore of Greenland.

The lack of a head on the prow of the skin boats,

may have two reasons, First the skins may have been made from whale

skins (???). Secondly, I believe the skins were removed from the frames

and used for shelters like we seem to find on the island to the left.

(See EXPLAINING LONGHOUSE

"FOUNDATIONS" ON LABRADOR COAST for a more detailed

discussion)

Greenland

'Eskimo' clans meeting to hunt whales

from Description

de histoire naturelle du Groenland, by Hans Egede, tr.

D.R.D.P. Copenhagen and Geneva, Frere Philibert (This image derived

from Canada's

First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from earliest times

by O. P. Dickason, Toronto, 1992)

As discussed in PART ONE: THE

ORIGINS AND EXPANSIONS

OF BOAT-ORIENTED WAYS OF LIFE : Basic Introduction to the Theory

aboriginal peoples, whether in the interior or on the seas, did not

wander aimlessly, but established annual rounds, visiting the same

campsites again and again every year, and each tribe established this

round and the harvesting sites as their 'territory'. Since the

boats were mainly paddled and not dependent on wind, their annual

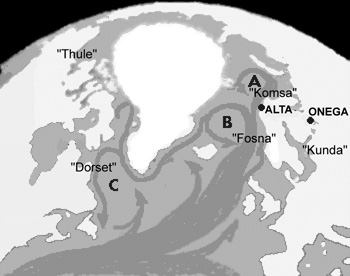

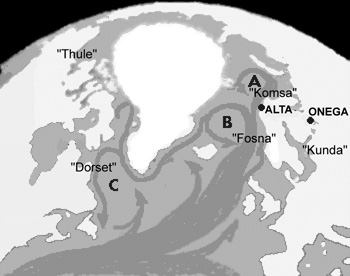

rounds would have been defined by oceans currents. The map below, shows

the currents of the North Atlantic and how we are able to identify

three 'territories'.

Map shows ocean currents

of the North

Atlantic and some of the names mentioned in this text. The names in

quotes represent archeological "cultures". ALTA and ONEGA name two

major locations of rock carvings showing boats, dating to 6000 years

ago. The letters A, B, C show areas where currents loop around. Since

early boats were not particularly wind-driven, they would have been

oriented to currents, and each of these loops could have defined a

tribe undertaking migrations that may have lasted many years before

returning to the same place.

Whale hunting tribal territories would have

developed according to the behaviour of whales and not just ocean

currents (What point are currents if they don't take boats to the

hunting/fishing places?). Whales migrated up and

down Atlantic coasts, both on the European side and the American

side. Obviously tribes on one side would in the long run diverge

from those on the other side, as a result of reduced contact. When the

whale hunting culture reached the Pacific, it would also have descended

down the Pacific coast, that also has whale migrations. They could have

descended as far south as California, since whales did. If you are a

whale hunter, would you not wonder where they went, and try to follow

them?

While whales and the search

for large sea animals in general, like also seals and walrus, may have

been the original reason for boldly venturing into the open sea (quite

scarey until one is used to it), once there, the sea-going hunters also

had access to new places to fish, and that would have caused the

culture to flourish and expand in some places, even without whales.

The Arctic Sea-People of North

America and Greenland - the "Thule" and "Dorset" Archeological Cultures

'OWNERSHIP' OF WILD ANIMAL HERDS

Hunting peoples became closely tied to the animals

they hunted. They did not wander at random and hunt whatever they

encountered. Those who hunted and gathered in the forests and marshes

did not think so much about owning the animals as in terms of owning

the rights to hunt at particular sites as defined by their annual

rounds.

However hunters of large herding animals defined

their territory in terms of a particular herd. Long before

domestication, the hunters of the herds thought of

themselves as 'owners' of those herds, and they both endeavoured to

foster the herd's health as well as defend them against foreign

hunters.

In the late Ice Age, the reindeer hunter tribes of

the North European

Plain would have stayed with the same herd generation after

generation. Their sense of territory was that herd, not the

land.

Each tribe respected the herd of the other tribe. There is no question

that something similar occurred with tribes that hunted horse and bison

herds.

This pattern can be extended to whale hunters. A

particular

tribe would consider themselves 'owners' of a particular pod of

whales.

The whales migrated up and down the coasts of the

continents. Thus one

tribe would be associated with whale migrations up and down the North

American coast and another associated with whale migrations up and down

the European coast. When the whale-harvesting culture reached the

Pacific, then tribes would be formed there too, establishing

their tribal territory to particular whale migrations. Whaling was of

course difficult, so more realistically, most of the year was probably

spent harvesting smaller mammals like walrus and seals, reserving the

whale hunt for the time when all the clans of a tribe congregated and

socialized - ideally annually - at one special location.

ARCHEOLOGICAL

CULTURES OF THE ARCTIC

Archeologists say that the Inuit of northern North

America and Greenland, originated from the archeological "Thule"

culture, which expanded rapidly west-to-east (in 500 years!) from

northern Alaska. The name "Thule" has no relationship to the historic

Thule of Pytheas which is

believed to refer to Iceland. The new culture, the new

technology, seemed to displace a former "Dorset" culture in the north.

The "Dorset" culture had arrived much earlier from the Greenland side,

beginning as early as 3000BC (5000 BP) about the time of the making of

the rock

carvings of seagoing skin boats.

Note that archeology

defines culture by artifacts. The replacement of "Dorest" with "Thule",

only means that a new set of tools and practices travelled east from

Alaska. It does not necessarily mean a massive migration of "Thule"

people. The new ways could have spread through contact, intermarriage

with minimal genetic replacement. Realistically it was both.

We know that about the

time of the Norse landings on North America there was a climatic

warming that led to Norse establishing farms on the Greenland coast.

Within a few centuries the climate cooled again and those farming

settlements were abandoned. During this warming spell, passages between

the arctic islands, normally blocked by ice could have been free of

ice, offering easy passage to seagoing tribes (ie carrying the "Thule"

culture) on the west side. To be specific, McClure Strait-Viscount

Melville Sound, Barrow Strait, could have had ice-free passages

easy to follow in skin boats. It is believed there was a similar

climatic warming at the start of the modern era ( ie after 0AD). The

"Thule" culture could have originated from the earlier "Dorset" culture

at an earlier time moving in the other direction (east to west) when

water passage was easy. Now the cousins were returning.

(The other

solution is that the "Thule" and Pacific whaling cultures originated

from whalers who migrated eastward from the White Sea over top of

Siberia, which may have occurred anyway, since real events are not

always simple ones, in spire of scholars wanting to simplify the

past. I tend to think the expansion of arctic seagoing people was

east-to-west for one simple reason - the Tamir Penisula sticks up

towards the north pole and even today for most of the year passing it

is blocked by sea ice.)

THE

BEST INTERPRETATION OF THE REPLACEMENT OF "DORSET" CULTURE WITH "THULE"

CULTURE

Thus, while it is imagined that in the relationship

between "Thule" and "Dorset" one people conquered the other,

it would have been at best a passive conquest - the ones with the

better tools and technique being naturally stronger and more

successful. While we can picture angry words and skirmishes between

those with the "Thule" culture and those of the previous "Dorset"

culture over hunting territories, we should not assume that the one

killed off the other.

Successful "Thule" technology would have been adopted by the original

peoples, the "Dorset", once they saw it, in much the same way as the

arctic peoples in modern times quickly adopted rifles and now

snowmobiles. Thus perhaps there is territorial conflict only in some

instances, and soon, after a few generations, the best of both cultures

merge into a new culture. In other words what is today called "Inuit"

is probably a combination of the best of "Thule" and "Dorset"

practices. Both cultures, obviously had to have been similar

to begin with, since both were seagoing cultures, originating

from the same circumpolar expansion of whale-hunters.

Today all the 'Eskimo' culture across

arctic North America is assumed to be from the "Thule" culture,

and is given the name "Inuit", but in truth, we do not have any way of

knowing to what extent the resulting Inuit culture of the North

American arctic, from Alaska to Greenland, contains elements of the

earlier archeological "Dorset" culture of people known by the Inuit

today as

"Tunit". Common

sense would suggest that the resulting

culture in the east around Greenland retained more "Dorset" elements,

while the culture in the west, near Alaska remained purely "Thule".

Also, is the modern Inuit language closer to the language of the

"Thule" or the "Dorset"? Or where they essentially of the same

circumpolar culture, differing only dialectically. Thus, for example,

it is possible that the "Thule" and "Dorset" culture already spoke

similar language, and both called themselves by a word like INNU, so

that when the two mingled, they quickly merged, after some generations

of intermarriage, into one "Inuit". One possibility is that the

Algonquian Native nations of the northeast quadrant of North America

originated from "Dorset" peoples pushed south along the Labrador coast,

and then after a time expanding inland up the rivers. In Quebec

the Montgnais and Churchill River Algonquians called themselves "Innu".

This fact tends to affirm that the "Dorset" people called themselves

"Innu".

Supporting the possibility that the difference

between "Dorset" and "Thule" culture may have been largely in their

material culture that archeology is finding and that their ethnicity

was similar, is the fact that

modern Greenland 'Eskimos' have legends that link them to the east

towards arctic Europe, not to the west. Greenland 'Eskimos' insist

without question they came from the east. Since archeology shows the

"Dorset" culture expanded east-to-west, it means the Greenland

'Eskimo' memory is related more to the "Dorset" culture, and further

east to arctic Europe. This makes sense because Greenland is the most

easterly of the 'Eskimo' peoples. More "Dorset" cultural descendants

would be found among the Greenland 'Eskimo' than Inuit of arctic

western Canada.

SHORTCOMINGS

OF ARCHEOLOGISTS' MATERIAL CULTURES

Archeology only studies the hard material

remains left by people. Their definition of "cultures" according to

artifacts can be highly misleading. For example we mentioned above the

"Kunda" culture; but were the "Kunda" culture really very different in

linguistic and cultural terms than the "Maglemose" culture? Similarly

were other "cultures" to the north and east really very different from

the "Kunda"? We have to recognize that people of the very same

ethnicity and language -- with only dialectic variation -- can follow

different ways of life! The differences are determined by the

forces in the environment in which they lived, and not by internal

changes. Indeed internally they could all remain the same, changing

only the technology and behaviour that they needed to deal with each

their own environment. Seagoing people developed material culture

suited to seahunting, river people developed material culture suited to

river life, marsh and bog people had yet other technologies and

behaviour. Humans can change their material culture very very

quickly and still remain the same, ethnically. For example, Chinese can

adopt American business-suits and cars and electronics, and still speak

Chinese, still eat their own traditional food, and still carry on their

own folk traditions. Another good example are Estonians and Finns, they

borrowed farming practices and from an archeological perspective they

ought to be Germanic speaking, but they are not.

Thus we have to be careful about assuming that the

"Thule" and "Dorset" archeological cultures were different ethnically.

They could have been ethnically only as different as, say, an American

and British person.

The Linguistic Ties Across the Arctic

TRACING THE LANGUAGES FROM "KUNDA" ORIGINS

If the theory that circumpolar waters became

populated by

the same culture, originating in whale hunters (and then pushed south

following the whales), then the evidence should exist in language

as well. With the new view of Finno-Ugric languages it is likely that

modern Estonian and Finnish is descended from

the language of the "Kunda" culture. Indeed history shows that peoples

of the east Baltic coast developed into intrepid seafarers, carrying on

trade across the northern seas.

Since sea-hunting culture does not

spring into being fully developed, the moose-head-boat sea-hunters

shown in the rock carvings from Lake Onega to the White Sea, must have

originated from the "Kunda" culture, where sea hunting in Baltic waters

first developed. The language of the "Kunda" culture must have

been Estonian-like.

It follows that the language

spoken by the whalers - yes the same ones in the illustration above

showing the capture of a whale - was derived from the "Kunda" people's

language, the same one from which Estonian and Finnish developed. If

these whale hunters then expanded around the arctic, it follows then

that we should be able to find Estonian and Finnish words that have

parallels in the Inuit language of the North American arctic,

consistent with many thousands of years of separation (These parallels

would not be strong enough for proper comparative linguistic analysis,

but enough to suggest support for the circumpolar whale hunter

migration theory.) Furthermore, we should also find Finnic words in

further expansions from these people, down the coasts.

Comparison of Inuit and Estonian/Finnish reveals

coincidences in basic

words, consistent with having had the same origin. As the following

sampling shows, parallels can be found in all the fundmental areas --

concepts relating to boats, fish, harpooning, hunting, and even some

family relations, Unlike the names of objects in the everyday

environment, words for these basic items at the core of a culture are

likely to

resist change and be preserved. Note that in the following study I use

Estonian as the primary language, looking up Finnish parallels to

Estonian. It is possible that if the study uses Finnish as the primary

language, additional good parallels can be found, especially if Finnish

has retained more archaic words.

In the absence of

independent ways of determining which Estonian/Finnish words have deep

roots, the approach to be used is to limit the Estonian/Finnish

vocabulary to

common words - such as is taught to children - based on the idea that

words deeply entrenched in basic vocabulary also tend to be the oldest,

transferred from generation to generation with little change. In

the past there have been "scholars" who have compared languages only by

thumbing through dictionaries. That approach will produce many absurd

results because in a dictionary, every word, old and new, original and

borrowed, has the same value. There is no way of determining from a

dictionary which are deeply entrenched in the language - and most

likely very old - versus those that have been recently invented or

borrowed to adapt to modern realities.

COMPARING

INUIT WORDS WITH FINNIC

Linguists say that every millenia,

as much as 80% of a vocabulary changes. But by the same token 20% may

represent core words that are so important that there is a reluctance

to change them. After 4-6 millenia, how many of those 20% unchanging

words continue to survive? It is possible that words that resist change

after 1000 years continue to resist change. The longer one uses a word,

the longer one wants to continue to use the word. What is significant

about the interpretations below is the number of examples there

are that relate to hunting, boat-use, land, sea, water, family, and

other core concepts important to a boat-oriented people. This tends to

indicate we are dealing with the core words that resist change.

Loanwords tend to manifest in names of new things, not core concepts.

The following is a brief summary of the better

words I have found in a relatively small lexicon of Inuit words. I

avoid the grey zone of other possibilities. The grey zone is better

investigated by linguists who can add further observations to justify

their choices. Here we give only those that really jump out

strongly, and are quite obvious - needing no extensive arguing.

The source of the Inuit words and

expressions tested in my brief study included only a few 1000

expressions. (The

Inuit Language of Igloolik, Northwest Territories,

Louis-J Dorais, University of Laval, Laval, Quebec, 1978). There is

wisdom in using common words and phrases in both languages, because it

ensures that comparison is made between the 20% or so core words that

resist change.

The following examples do not follow any

particular order. I note them in the order in which I encountered them.

Note that to make the argument strong, I have not included 'borderline'

(grey zone) parallels. Nor is the source of the Inuit words exhaustive

as only a small lexicon was consulted (A small lexicon is not

necessarily bad, as small lexicons will tend to present the most common

words, and those tend to be generally the most entrenched and oldest).

Nor are any obscure Estonian or Finnish

words used in the analysis, to ensure that we are dealing with core

vocabularies which are most likely to have endured. Note also that

anything that is grammatical in nature tends also to be old, as

grammar, representing structure, also tends to resist change.

Inuit

language resonances with Estonian/Finnish

1. Beginning with Inuit suffixes, the one that

leaps out first is the suffix -ji as

in igaji 'one who cooks'. This

compares with the Est/Finn ending -ja

used in the same way, to indicate

agency, as in õppetaja 'teacher, one who

teaches'. Indeed Livonian

(related to Estonian) uses exactly -ji

2. The Inuit infix -ma-

as in ikimajuq 'he is (in

the situation of being) aboard'. The Estonian/Finnish use of -ma/-maan

in a similar way describes a situation of 'being'. While modern

Estonian uses -ma as the

ending marking the first infinitive, it

originated from 'a verbal noun in the illative (into)' (J. Aavik).

3.The Inuit -ksaq

as in nuluaksaq 'material for

making a net', strongly resembles the Estonian translative case ending

-ks so that Estonian can say võrkuks

'(to be made) into a net'. The

Inuit additional -aq is a

nominalizer, and Estonian also has -k

as a

nominalizer. Although a little contrived, one could say võrguksik and

it would mean 'something made into a net'

4. In Inuit the ending -ttainnaq means 'the same

for' as in uvangattainnaq 'the same (another?)

for me'. In

Estonian/Finnish there is teine/toinen,

meaning 'another, the other'.

5. In Inuit there is -pallia as in piruqpalliajuq

meaning 'it grows more and more. This compares with Estonian/Finnish

palju/paljon 'much, many'.

Inuit also has the expression pulliqtuq

'he

swells' which compares with Finnish pullistua

'to expand, swell'.

6. In Inuit there is -quji

as in qaiqujivunga

meaning 'I ask to come.' This compares with Estonian/Finnish küsi/kysyy

'ask'. Note also that the example qaiqujivunga presents qai- which

resembles Estonian/Finnish käi/käy 'go'. Thus we can invent via

Estonian for example "käi-küsi-n" which can be construed as 'I

ask-to-go'.

7. In Inuit there is -ajuk as in tussajuq

meaning

' he sees for a long time' or the similar -gajuk which makes the

meaning 'often'. This compares with Estonian/Finnish aeg/aika meaning

'time'. This pattern has parallels in Algonquian Ojibwa language

(people of the birchbark skin boat)

8. In Inuit there is -tit as in takutittara

'I

make him see' which compares with Estonian/Finnish tee/tekee 'make, do'.

9. In Inuit there is suluk 'feather' which

compares with Est./Finn sulg/sulka

'feather'. This is one of the

clearest parallels.

10. Inuit kanaaq ' lower part of leg' versus

Est./Finn kand/kanta 'heel'

11. Inuit kingmik 'heel' versus Est./Finn king/kenkä 'shoe'

12. Inuit nirijuq 'he eats' versus Estonian närib 'he chews'

13. Inuit saluktuq 'thin' versus Est./Finn. sale/solakka 'thin'

14. Inuit katak 'entrance' versus Est./Finn. katte/katte 'covering'

15. Inuit ajakpaa 'he pushes it back' versus

Est./Finn. ajab/ajaa 'he

pushes, shoves (it)'

16. Inuit kina? 'who?' versus Est./Finn. kelle?/kene? stem for 'who?'

17. Inuit kikkut?

plural 'who?' versus

Finnish ketkä plural 'who?'

(Estonian uses the singular for plural)

18. Inuit kinngaq

'mountain' versus Est./Finn. küngas/kunnas

'hill, hillock, mound'

19. Inuit iqaluk 'fish' versus

Est./Finn. kala/kala 'fish'.

20. Inuit tuqujuq 'he dies' versus Est. tukkub 'he dozes'.

22. Inuit iluaqtuq

'suitable comfortable' versus Est./Finn. ilu/ilo 'beauty joy delight'.

23. Inuit akaujuq

is another word for 'suitable, comfortabe'

and might be reflected in Est./Finn. kaunis/kaunis

'beautiful, handsome'

24. Inuit angunasuktuq

'he hunts' or anguvaa 'he

catches it' compares with Est./Finn öngitseb/onkia

'he fishes, angles'

or hangib/hankkia 'he

procures, provides'

25. Inuit nauliktuq

'he harpoons' versus

Estonian/Finnish naelutab/naulitaa

'he nails'. But closer to the

concept of harpoon is nool/nuoli meaning

'arrow'. (Some words

here have echoes with English words - like to nail - because English

contains a portion of words inherited from native British language

which was part of the sea-going people identifiable with the original

Picts. Some also have echoes with Basque which also has connections

with ancient Atlantic sea-peoples)

26. Another word of great antiquity in Inuit

is

kaivuut 'borer' which

compares with Est./Finn. kaev/kaivo

'something

dug out' today commony applied to a hole dug out of ground.

27. Inuit qaqqiq

'community house' versus Estonian/Finnish kogu/koko 'the whole, the gathering'

28.Inuit alliaq

'branches mattress'

compares with Est./Finn. alus/alus

'foundation, base, mattress, etc'

29. Inuit ataata 'father' compares with

Estonian taat/ 'old man,

father'

30. Words for family relations are words not

easily removed, and Inuit produces more remarkable coincidences: Inuit

ani 'brother of woman',

compares with onu 'uncle' in

Estonian, but in

Finnish eno means exactly as

in Inuit, 'mother's brother'. A similar

word also exists in Basque (anaia =

'brother') since Basque has

connections to the ancient Atlantic sea-going peoples

31. Inuit akka

refers to the 'paternal uncle'. In

this case Estonian uses onu

again, but Finnish says sekä

'paternal

uncle'. See later also ukko.

32. A most interesting Inuit word is saki meaning

'father, mother, uncle or aunt-in-law'. This suggests an institutional

social unit. In Estonian and Finnish sugu/suku

means 'kin, extended

family' and is commonly used in for example sugupuu 'family tree'.

33. In Inuit, paa means 'opening'. This compares

with Estonian poeb 'he crawls

through'. The stem is used in

poegima/poikia 'to bring forth

young', and is commony used in

poeg/poika meaning 'son',

'boy'; but its true nature is actually

genderless.

34. Inuit isiqpuq

'he comes in' is interesting in

that it shows the use of the S sound in concepts of 'inside' which is

common in Estonian and Finnish, as in sisu/sisu

'interior' or various

case endings and suffixes.

35. Another very basic concept is seen in Inuit

akuni 'for a long time', as it

relates to Est./Finn. aeg/aika

'time',

kuna/kun 'while', and kuni/--- 'until'.

36. Inuit unnuaq 'night' compares with

Est./Finn. uni/uni 'sleep'.

37. Inuit sila

means 'weather, atmosphere', and

compares with Est. Finn. through sild/silta

'bridge, arc' if we use the

ancient concept of the arc of the sky.

38. The Inuit aqqunaq 'storm' is reminiscent of

the earlier word akka for

paternal uncle. It may imply that the storm

was considered a brother of the Creator. The word compares to the

Finnic storm god Ukko. In

Finnish ukko also means 'old

man'. Inuit also

has aggu 'wind side', which

implies the side facing the storm. In

Estonian/Finnish kagu/kaako

means 'south-east'. Prevailing winds

travelled from the north-west to the south-east; thus the word may

originate in a relationship to wind.

39. Inuit puvak

'lung' connects well with Estonian

puhu 'blow'. Finnish has

developed the word to mean 'speak'.

40. The Inuit nui(sa)juq

'it is visible' may have

a connection with Estonian/Finnish näeb/näkee

'he sees'. In modern

Estonian, the concept of 'visible' could be expressed by näedav.

Algonquian Ojibwa has a similar word.

41. Inuit uunaqtuq

'burning' relates to Est/Finn.

kuum/kuuma 'hot' but most

strongly to Finnish uuni

'oven'.

42. Inuit kiinaq

means 'edge of knife'. This compares with Est./Finn küün/kynsi 'fingernail'

43. Inuit aklunaaq 'thong, rope' compares

with Est./Finn. lõng/lanka

'thread'.

44. Inuit words sivuniq

'the fore-part' compares

exactly with Finnish sivu

'side, page'. But also Inuit sivulliq

'past',

compares with the alternative Finnish use of sivu in the meaning 'by,

past'. (This kind of parallelism in two meanings, is powerful in

arguing a connection since it is not likely to occur by random chance.)

45.The Inuit kangia

'butt-end' compares with

Est./Finn. kang/kanki 'lever,

bar' or kange/kankea 'strong,

intense'

46. Inuit uses pi to mean 'thing', which has no

parallel to Est. /Finn., however other words with PI show interesting

parallels: Inuit pitalik means

'he has, there is' which may compare

with Est./Finn. pidada/pitää

meaning either 'to hold' or 'to have to'.

Inuit uses piji for 'worker'

and pijariaquqpuq means 'he

must do it'.

Also pivittuq means 'he keeps

trying but is unable to', which resembles

Est./Finn. püüab/pyytää 'he

tries, he entreats'.

47. In Inuit traditions and indeed throughout

the

northern hunter peoples, the man was always the hunter. This is

reflected in Inuit ANG- words. We have already noted anguvaa 'he

catches it'. There is also angunasuktuk

'he hunts', which is obviously

related to anguti 'man,

male', and angakkuq 'shaman'.

Estonian

kangelane, 'hero', but

literally 'person of the land-of-strong' may

have a relationship to the concept of 'shaman', and also to the earlier

Inuit concept within kangia

mentioned above.

48. Inuit also has several KALI words that have

Estonian/Finnish correspondences. Inuit qulliq 'the highest'

corresponds with Est/Finn. küll/kyllä

'enough, plenty'; Inuit kallu

'thunder' corresponds with Est/Finn kalla/---; Inuit qalirusiq 'hill'

resembles Est./Finn. kalju/kallio

'cliff'.

The most interesting Inuit words are

those that relate to the sea, land, and mother, because they will

reveal whether in the Inuit past there existed the same boat-people

world-view also found in northern Europe.

49. Inuit has amauraq for 'great grandmother' a

word that might reate to Inuit maniraq

'flat land' . These two words

relate to Estonian/Finnish ema /

emän- 'mother/lady-' on the one hand,

and maa/maa 'land, earth,

country' on the other. As I discuss

elsewhere, early peoples saw the world as a great sea with lands in it

like islands, thus the original concept of a World Mother was that she

was primarily a sea. (This may explain why Danish bog-people threw

offerings into the sea!). Thus the original word among the boat peoples

for both World Plane and World Mother was AMA. The meaning of AMA did

not specify land or sea. The proof of this concept seems to be found in

Inuit maniraq since it

contains the concept of 'flat', as well as in

Inuit imaq 'expanse of sea'

which expresses the concept of 'expanse'.

Estonian too provides evidence that the original meaning of AMA was

that of an 'expanse', the World Plane. For example there is in Estonian

the simple word lame

("lah-meh") means 'wide, spread out'. In addition

there are uses of AMA which refer to a wide expanse of sea. One

manifestation of the word is HAMA, as in Hama/burg the original form of

Hamburg . Also there is Häme, coastal province of Finland, etc. which

appears to have had the meaning of 'sea region'. Historically,

according to Pliny, the Gulf of Finland was once AMALA, since he wrote

that Amalachian meant 'frozen

sea' (AMALA-JÄÄN). The words for 'sea' in

a number of modern languages, of the form mare, mor, mer, meri can be

seen to originate from AMA-RA 'travel-way of the world-plane'. The

equating of sea with 'mother' interestingly survives also in French in

the closeness of mère

'mother' to mer 'sea'. The

intention of this

discussion is to show that the worldview appears to reside within Inuit

language as well, suggesting distance origins of Inuit in the same

boat-peoples, the same great expansion of mainly around 6000 years ago.

We are seeing traces dating back a very long time.

50. However, we must also note that while

Inuit

'great grandmother' is amauraq,

the actual Inuit word for 'mother' is

anaana Is it possible Inuit

used N to distinguish between the sea-plane

and land-plane. Indeed their word for 'land, earth, country' too

introduces the N -- nuna. Or

perhaps the N is borrowed from the concept

of femininity because we also find Inuit ningiuq 'old woman' and

najjijuq 'she is pregnant'

which relate to Estonian/Finnish stem

nais-/nais meaning 'pertaining

to woman'.

51. But then again, Inuit also says amaamak for 'breast'

which compares to Estonian/ Finnish amm/imettäja

for '(wet) nurse'.

There is aso Est./Finn. imema/imeä

'to suck'.

52. But, the words which are of greatest

interest are words for 'water'. If there is anything that all the boat

people have in common is the act of gliding, floating, on water.

It appears that in Inuit the applicable

pattern is UI- or UJ- same as in Estonian/Finnish. uj-, ui-, Inuit

uijjaqtuq means 'water spins'

whose stem compares with Estonian/Finnish

ujuda/uida 'to swim, float'.

Interestingly Inuit uimajuq

means

'dissipated', but Estonian too has something similar in uimane 'dazed'

, demonstrating that both use the concept of 'swimming' in an abstract

way as well. (Indeed the concept at least survives in English in the

phrase "his head swims" to mean being 'dazed'.) Considering the Inuit

infix -ma- meaning 'in a

situation, state', it seems that the stem in

both Inuit and Estonian cases is UI, and that -MA- adds the concept of

being in a state, situation.

53. Other notable words might include Inuit umiaq

'boat'. If umiak is a

condensation, and the original Inuit word was

UIMIAK or even UIMAJIK, then once again Estonian too could combine UI

and MA and JA and the K nominalizer, and get UJUM/JA/K. While an

invented word, Estonian would interpret it as 'something that is an

agent of the situation of swimming, floating'. Also Inuit has umiirijuq

'he puts it in the water'.

54. The most interesting Inuit words to me, are

tuurnaq 'a spirit' and tarniq 'the soul', because they

compare with the

name of the Creator across the Finno-Ugric world. It appears in Finnish

and Estonian mythology as Tuuri,

Taara, etc. And the Khanti

still

concieve of "Toorum". The

presence of the pattern in Inuit is proof

that it has nothing to do with the Norse "Thor", but that "Thor" is

obviously an adoption by Germanic settlers into Scandinavia of the

aboriginal high god. Norse mythology contains other features that can

be traced to the Finnic mythology of the aboriginals into which they

settled, when Scandianvia was Germanized during 0-1000AD.

GRAMMAR: In addition to many basic words, such

as given

above, there are similarities between Finnic and Inuit grammar. The

most noticable is the use

of -T as a plural marker, or -K- to

mark the dual. (Although neither Finnish nor Estonian retains

declension of a dual person, it is easily achieved by adding -ga

'with' into the declension, which is the Estonian commitative case

ending.)

THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE - PART OF A WHOLE

The linguistic similarities between the Inuit language and our

examples

of Finnic - Estonian and Finnish - taken in isolation might not be

convincing to a critically-minded linguist. However, in this study we

cross many fields, and do not concentrate on only one field. Thus while

the linguistic argument by itself is not earthshaking, when we add to

it the other cultural and archeological coincidences, images from rock

art, and so on - IT ALL ADDS UP.

As it is when a detective analyses evidence at a crime scene,

collecting only fingerprints may not say very much, but if he assembles

other evidence and then analyses it all for what it all suggests as a

whole, then a strong story emerges. This kind of methodology is

familiar to archeologists, who can be described as detectives of

ancient evidence. Linguists, on the other hand are like fingerprint

analysts: with a narrow focus, and who want to find the strong evidence

within their analysis.

Thus the reader is asked not to made

judgements only within their own field, but add to it evidence from

outside their field. Linguists should also look at the archeology,

archeologists at the linguistic evidence, and both at other evidence

like the nature of North Atlantic currents, and so on. The further we

go back in time, the less we can rely on only one field for answers,

and the more we have to bring together data from every possible

direction, to make the case.

The Further Expansions of the Seagoing

Skin-Boat People

READING

THE EVIDENCE IN ARCTIC SCANDINAVIA

The original sea-people of the North Atlantic were

probably like what

we see in the illustration of Greenland 'Eskimo'/ Inuit -- with

enormous skin boats, capable of holding up to fifty men, women, and

children, as they travelled from island camp to island camp.

If you look at the

illustration, even though the few kayaks in the foreground are like

typical kayaks, the skin boats look different from the umiaks in the

western arctic. They have extensions on both ends, perhaps creating

handles so that men can pick them up easily. They look like a well

developed vessel, the result of a long history of use in such activity.

Note also how they made camps on islands.

The rock carvings found at Alta Norway (see

PART THREE: SOUTHWARD

MIGRATIONS OF CIRCUMPOLAR SKIN-BOAT PEOPLES), tell a story

about people coming there

to harvest the rich sea life off the arctic coast of Norway, where the

warm waters of the Atlantic Drift (originating as the Gulf Steam on the

American coast) ended up. Originally they would have travelled there

seasonally, and then returned south in the dark and cold winter. But

then some stayed. The "Komsa" archeological culture at the top of

Norway, that camped all winter at the mouth of the Teno River, was one

of the first cultures that remained all year, enduring the sunless

months. The Alta carvings also suggest that there were people there who

stayed, because of the many images of boats with reindeer heads on the

prows, not moose heads. Reindeer were smaller, and many skins had to be

sewn together, but if one did not descend south into the forests to

hunt moose, that was what you had to use. The large moose-head skin

boats, such as depicted in the White Sea rock carving of whale hunting,

speak of returns south into Lake Onega, where winter was spent hunting

moose on skiis (There is an image at Lake Onega of a man following a

moose on skiis).

The head on the prow of a vessel

is a

phenomenon that has endured down through time, and its last

manifestation has been the hood ornament on the modern automobile or

truck, particularly if the ornament represents an animal. In culture we

do such things, and we do not know why; but some customs can have roots

that are many thousands of years old.

This

map shows ocean currents for the

entire world, plus in pink, obvious routes that boats without sails

would have taken, using currents to move them along. For explanation of

names UINI, see background article UINI- UENNE - UENETI: Are

Ancient Boat People identifiable by Names? The so called "dragon

boats" in Japan are obviously descended from the moosehead skin boats

too, as much as the Viking "dragon boats". Once boats were made of wood

skin, the origins of that head at the front was forgotten and

boat-builders began to play with it. Whale-hunting traditions are

still remembered down the Pacific coast of North America as well,

notably around Vancouver Island and down the Oregon coast.

The head of the animal from which the skin

was obtained appears

to have been an important tradition in sea-going traditions. It

is a tradition of vehicles created from putting a skin on a

frame. It follows that in addition to language, another feature

that will help us track the expansion of the sea-going boat peoples

(but not the dugout-boat peoples), is evidence of the animal head

at the prow.

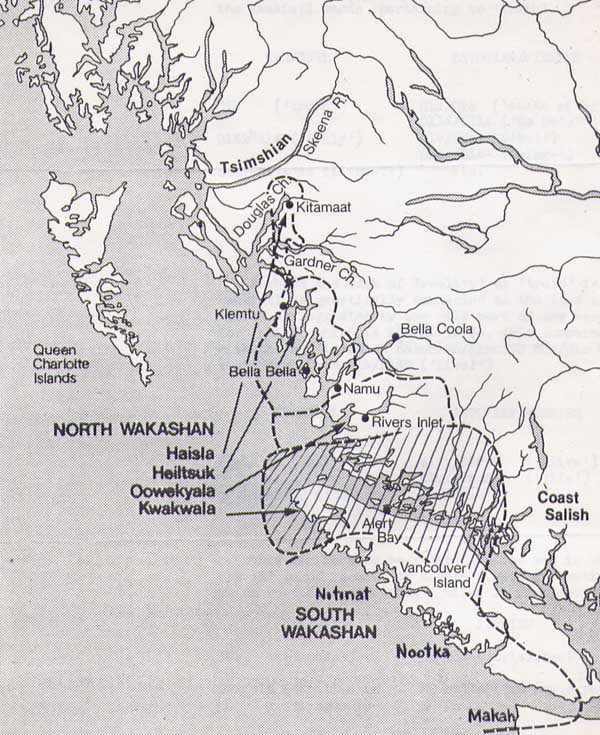

Whale-hunting traditions have

endured on the Pacific coast, particularly in Native peoples of the

region around Vancouver Island and to its south.(Peoples of the

"Wakashan" languages) There, memories of whaling are still strong, and

attempts are being made to recover the culture. If you look at the

graphics painted on the large dugouts of the Pacific coast, you will

see eyes painted on the front. If asked, the artist may say it is to

help guide the way, but it may tell another story. Because of the giant

cedar trees of the Pacific coast, whaling peoples arriving there were

able to return to the creation of seagoing dugouts. They may have

arrived in skin boats made of whale skin, with the whale head

represented by painting its eyes at the front. Converting to the cedar

dugout, the continued to paint the eyes at the front. It had to have

occurred this way, because such a practice of representing the head of

an animal at the front has never existed in the dugout boat tradition.

The coincidence between Pacific coast seagoing dugouts having an eye

painted on the front, and the whaling traditions cannot be assigned to

random chance!!

SOUTHWARD

MIGRATIONS

Thus, besides circumpolar expansion of the

sea-going skin-boat peoples, there was venturing southward. The main

inspiration for southward exploration would have been the north-south

migration of some species of whales. Encountering whales at the south

tip of Greenland, the whaling people could have followed them as they

left, down the coast of Labrador. But already whaler peoples in arctic

Norway could have followed whales too as they migrated back south along

the coast of Europe.

On the North American side, this

southward venturing could

have led to the birth of the Algonquian

Native cultures, whose languages at the time of European

colonization (16th century) was found to cover the entire northeast

quadrant of North America, in a manner consistent with boats making

their way up all the rivers that drained to the coast. The Algonquian

boats were dugouts everywhere except along the coast and where birch

trees were plentiful. Along the coast there were skin boats (including

those made of moosehide), and in the northern regions that had birch

bark, skin boats were made of skins of birch bark sewn together.

Obtaining birch bark was clearly easier than obtaining a moose hide.

Besides, a moose hide had other uses.

If we are looking for the

survival of the older "Dorset" traditions, it would probably be in the

Algonquian cultures. Indeed the Great Lakes Algonquian legends speak of

origins in the east, at the mouth of the Saint Lawrence. Newfoundland

had up to historic times a Native group called the Beothuks, whose

culture first manifested there in the early centuries AD. But we

cannot dismiss the possibility that there have been many waves of

oceanic peoples coming across the North Atlantic in skin boats and

venturing southward along the Labrador coast, moving with the same

winds and currents as the Norse around 1000AD.

On the European side there would have been southward

migrations too. Archeology identifies seagoing peoples on the

Atlantic coast of Europe as early as 4500BC, on account of the

"megalithic" (made of enormous stones) constructions from southern

Portugal to northern Britain, taking either the form of large burial

chambers covered with mounds, or stone circles and alignments. The

oldest megalithic stone alignments are found at Carnac, France, in

southern Britanny. The famous "Stonehenge" was a relatively late

development from the same general culture. The oldest

constructions were all found close to the sea, and widely distributed

in southern Portugal, Brittany, coasts on either side of the Irish Sea,

Orkney Islands, and even across to the north end of the Jutland

Peninsula by 2000BC. It suggests a trading people that eventually

promoted their culture inland up the rivers, eventually making eastern

Europe generally a culture of this nature.

These mysterious people certainly knew

how to travel in the open sea, and may have created more wealthy

cultures towards the south, off Portugal, and been the source of the

legends of Atlantis, first brought forward by Plato, which he claimed

ultimately came from Egyptian priests. They may have crossed the

Atlantic in the middle, leaping from island to island, with the Azores

in the middle of the Atlantic being the half-way point.

But the southward-migrating sea peoples, may

have merged in their southward migrations with dugout-peoples, and the

skin-on-frame approach of boat design, caused the evolution of the boat

made of planks on a frame. The original dugout became the keel,

and ribs arising from it could then take boards, to initiate a new

approach that combined the best features of both original designs.

The most important principle in boat design was the

displacement of water. The boat with a hull that displaced water with

essentially air achieved greatest buoyancy with least weight. The frame

with skin/hull was the way to create to greatest water displacing space

with least materials.

These images

from

the Alta carvings

depict skin boats made of reindeer skins engaged

in fishing with nets

Regardless of how Atlantic seafarers evolved towards

the south,

their northern cousins carried on generation after generation. The

activity was not focussed entirely on large sea-mammals (whales,

porpoises, seals, walrus, etc) but there was plenty fishing. Nets could

bring in large quantities which could then be salted and smoked.

If these seagoing skin boats were

at Alta, they were also elsewhere in the sea too, down the Norwegian

coast, and in the British northern isles.

SEAGOING

SKIN BOATS OF THE BRITISH ISLES

The sea-going peoples of the

British northern isles obviously originated from the arctic skin boat

peoples because they have always used skin boats. When walrus became

extinct in the British northern isles, the people there, the "Picts",

made skin boats from ox-hide. The Irish called them curraghs, the

Romans curucae. The

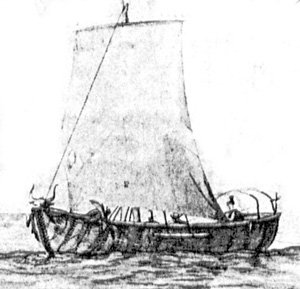

following illustration comes from an 18th

century illustration. To my amazement, it appears to have an

oxhead, at the prow, adhering to the ancient tradition of the

head of the animal whose skin was used being put at the prow.

18th century illustration shows 'wild Irish' in a 'curragh' - a

skin boat of ox hides - note the head of the ox at the prow,.

suggesting an origin in the arctic Norwegian skin boats

Author Farley Mowat, has searched historical

material for everything he

could find about the skin-boat peoples of the northern British Isles,

and established from historical quotes with great certainty of British