1.MAGLEMOSE AND KUNDA ORIGINS

The Post-Glacial Development and

Expansion of Boat-peoples

Synopsis:

At the end of the Ice Age, the world

climate was warming very rapidly -becoming as warm or warmer than today

by about 10,000 years ago, when the great glaciers were still very

large. This warming caused the northern lands to be flooded with

water, and turn former reindeer tundra into marshlands, lakes, rivers

and seas. Reindeer hunters had to give up their tradittional reindeer

hunting and adapt to the watery environment, including boats just to

get around. Although humans were smart enough to

devise rafts to cross bodies of water we are not by nature

water-creatures; thus the evolution of a part of humanity into a life

using boats and getting around on water could not have occurred

spontaneously just anywhere. It had to have occurred in a place where

there was no other alternative; where survival depended on it, and the

pressure lasted many generations. Through

natural selection those groups who devised the best ways of dealing

with the watery environment were the ones who produced the largest

populations and flourished. The following presents the basic

story - including some original discoveries - about the

appearance and expansions of a boat-oriented way

of life that marks an early stage in the evolution of Europe after the

Ice Age. This side of the European past has never before been told,

because traditionally scholars have focused on the land migrations and

the evolution of

farming and sedentary civilizations particularly in the Indo-European

tradition. Everyone imagines that European civilization owes its

existence to farming, but it owes as much to the development of

boat-oriented ways of life as it created the transportation and trade

that tied the civilization together.

Boat People Emerge from European

Reindeer People

FROM CLIMATIC,

GEOGRAPHIC AND ARCHEOLOGICAL

INFORMATION

The story begins at the

height of the Ice Age, when glaciers cover the entire north part of

Europe. In southern Europe there were people who lived in caves and

hunted bison, horses, reindeer and other large animals who lived in

plentiful grasslands or steppes, or towards the north permanently solid

tundra.

FIG 1

Map 1.

The Ice Sheet over the north of Europe.

Humans

who followed Reindeer, Bison,

Horses, Aurochs (wild cattle) and other migrating herds were

distributed according to the

migration patterns of these herds. Missing from the map is mammoths,

but mammoths became extinct in the course of the Ice Age retreat . As

the Ice Sheet withdrew and humans

began expanding northward, the first split was between the reindeer

hunters who occupied the tundra of the North European Plain, and the

descendants of the horse and bison hunters who were forced to adjust to

the

disappearance of grassy plains and plains herds.

Map 1.

The Ice Sheet over the north of Europe.

Humans

who followed Reindeer, Bison,

Horses, Aurochs (wild cattle) and other migrating herds were

distributed according to the

migration patterns of these herds. Missing from the map is mammoths,

but mammoths became extinct in the course of the Ice Age retreat . As

the Ice Sheet withdrew and humans

began expanding northward, the first split was between the reindeer

hunters who occupied the tundra of the North European Plain, and the

descendants of the horse and bison hunters who were forced to adjust to

the

disappearance of grassy plains and plains herds.

But when the Ice Age came to an end, the climate

warmed, and the southern parts of Europe became increasingly forested.

Grasslands and steppes vanished, and brought an end to herds of many of

the

steppes animals. Bison and horse herds migrated into Eastern Europe

where the

climate remained dry and there were still open country with grassy

steppes.. (Possibly

those hunters who followed them were the source of the '

Indo-Europeans' who adjusted to the decline in large animal herds by

starting to manage them - the first step towards domestication.). On

the other hand reindeer were animals who lived on

the tundra plain north

of the tree line. Forests could not swallow up tundra in the same way

they could swallow up steppe grassland, because trees could not grow in

arctic

conditions. Thus there was always a northern limit to trees, and beyond

that a tundra plain which could be inhabited by reindeer. Those humans

who sought to continue the way of life of the Ice Age, needed only to

shift north with the reindeer as they kept north of the tree

line.

REINDEER PEOPLE

The story of the boat people begins with the reindeer hunters.

Archeology reveals that the latest reindeer

hunters in continental Europe were in the region of Germany and Poland

around 13000

years ago. These were

about 90% dependent on reindeer, and therefore had needed to follow the

reindeer north as the climate

warmed. The northward shift would have been so gradual the reindeer

people would not have been aware of it; but over hundreds of

generations the northward shift added up to a great distance. By about

8000 years ago they would have been in the northermost reaches of

Greater Europe. As long

as their circumstances and way of life was unchanged they carried

forward the original language and culture of homo sapiens of the Ice

Age.

During the continuous northward shift of the

tundra, the reindeer hunters remained in arctic conditions. Staying in

arctic conditions the reindeer

followers continued to develop increasingly pronounced

mongoloid features, which are considered adaptations to the arctic.

(Eye squint against glare of snow, flat face to prevent wind flowing

over the face, squat body to reduce heat loss, etc. On the other

hand, those people of the Ice Age who abandoned the arctic conditions

early, did not have the natural selection forces on them and so, in

southern Europe, the arctic racial features are absent.

It follows that the modern peoples with highly

arctic

mongoloid features and traditions of reindeer hunting/herding - such as

the

Samoyeds of arctic Russia - are descended from the reindeer hunters. We

can also include the reindeer Saami in arctic Scandinavia today.. The

Samoyeds around the Tamir Peninsula are quite separated from the

Saami of arctic Scandinavia and one might wonder if it is valid to link

them together. In my view the Saami represent a mixing at a later stage

between reindeer and boat peoples in arctic Scandinavia. As

you will see later, when the glaciers shrunk over Scandinavia, the

northern part was free first and it would have been at that time

that the Reindeer-Saami ancestors entered the arctic regions.

The

boat peoples who went north to hunt the sea life of arctic waters in

skin boats would have encountered and mixed with the already

established reindeer hunters at that time. (See later)

ORIGINS OF THE BOAT PEOPLE

While the reindeer people were gradually

following their herds northward and the North European Plain turned

into bogs, lakes, and forests, the descendants of the people who

remained behind were adapting to new conditions.

How did some of the reindeer people get left behind? Whereas the

reindeer herds and their hunters could easily shift northeast and stay

above the tree

line from the

region now Poland (look up the archeological Swinderian Culture), towards the

west, in what is now Germany) the reindeer were unable to

continue north as the sea blocked the way, and these reindeer hunters

(look up Ahrensburg Culture) were

the first to have to adapt to the warm, waterlogged, landscape. The

last of the Western

European reindeer herds were hunted almost to extinction in the British

Isles.

As the originally

solid frozen land

turned to bogs and forest and the reindeer herds dwindled, the tribes

in these regions had to gradually turn to other animals to survive.

From

Poland

west to Britain, humans soon

found themselves in a marshy land where it was difficult to walk . That

began the environmental pressure that promoted a way of life moving

about in canoes made from logs. This original boat-people culture has

been called the Maglemose Culture.

Not all the reindeer hunters in the region of Poland

(Swinderian Culture) had been able to continue with the reindeer and,

borrowing from the dugout boat innovations of the expanding Maglemose

Culture, they made large dugouts capable of going out to sea and

hunting seals and whales. Perhaps colonies of seals or walruses

reminded them of herds of reindeer and they were able to transfer

skills in hunting reindeer to hunting sea animals like seals. It is

important to note that in reindeer hunting there may have been the

practice of ambushing reindeer from rafts as they were crossing rivers.

This would be a precedent that would be useful. Creating a boat for

hunting was not completely without precedent. These first seagoing boat

people are archeologically known as the Kunda Culture.

These descendants of both late Swinderian and early Maglemose Culture

were, like all boat people became, extremely mobile (since they could

travel much further and faster in boats than even reindeer hunters on

solid ground on foot). Like all hunter-gatherer people at any time in

history, they had a sense of ownership of the lands and waters in which

they hunted and it was their territory. They managed and defended their

territory - each family in a tribe their subterritory - from

rival tribes. But because of the mobility their range was very large.

Judging from similar situation in North America with canoe-using

Algonquian people a few centuries ago, the range of movement could be

3000 km wide, along the paths of water routes, of course. The Kunda

Culture was about 1000 km of coast, and extended up into what is now

Finland, and probably east as far as Lake Onega. But these were

seagoing people. They were more likely to expand, when their

populations grew, up to the arctic ocean. The dugouts intended for

rivers and lakes, had probably already been expanding since the

Maglemose Culture, because archeology has found evidence of that kind

of culture on banks of prehistoric rivers and lakes, as far east as the

Ural Mountains region.

Thus the Maglemose Culture was the beginning of the

boat peoples. During the several thousand years since it emerged around

Denmark, around 11,000 years ago, it expanded eastward through all the

marshy interior regions. The seagoing offshoot, the Kunda Culture,

began a second trend which saw boat people expanding north to the

arctic ocean, and inventing skin boats because the trees were too small

for making large seagoing dugouts.

In terms of the original dugout canoes, remnants of

ttheir dugout

canoes dating to as much as 10,000 years ago have been found preserved

in bogs from Britain to Finland. If actual remains of dugouts cannot be

found, the stone adze reveals the making of dugouts. The dugout was

made by burning the wood and using the adze to chop away the coals in

the direction you wanted the burning to go. Where coals were not

removed, the burning stopped since the coals created a barrier to

oxygen needed for burning. (The method is still found

among the Khanty/Ostyaks of the Ob River.)

Thus to summarize, the best theory to explain

archeological discoveries as well as the results in surviving

languages. is that the

boat people began as people who were unable to continue as reindeer

hunters in the central and western parts of the North European Plain

and gradually adapted to a watery and forested landscape which featured

dugout canoes to get around. Archeology sees the new way of life in the

Maglemose culture and Kunda Culture, then sees this culture spread

eastward via the

waterways changing slightly with new circumstances. Archeologists like

to give different "culture" names based on location,. or some special

material culture feature, but the original expansion was still

essentially the Maglermose Culture.

The expansion occurred during about 11,000 - 8,000

years ago. During that time all the waterways connected to the Baltic

and North Seas (the regions of the Maglemose and Kunda origins) would

have been explored and all the new tribes that arose from the

population explosion would have found their place within various water

systems (since they travelled by canoes). Because boat people travelled

so widely,.with range of seasonal migrations maybe 5 times larger than

what was covered earlier by the reindeer hunting people, they would

have had frequent contact with other tribes, and when there is contact

over such large distances, the language will tend to be quite uniform.

(A good example would be of course the wide distribution of the

Algonquian languages covering the northeast corner of North America.

The Cree language for example, covered 3000km around Hudson Bay, with

only three dialects. Just to their south were the Ojibwa (Anishnabe)

whose language was close enough to Cree to communicate. The evidence is

there that there was a common language similarly in boat oriented

hunter-gatherers in the region between Scandianvia and the Ural

Mountains, with only dialectic variation according to different water

systems.

What was the language of the original boat

people?

The

short answer is that it is most proper to speak of the "Finno-Ugric"

languages, since using "Uralic" will include the Samoyeds, which are

descended from Asian reindeer peoples, and have no connection to

water-based life. The "Uralic" family tree concept, which may still be

found in books, is to be abandoned. It originated in the 19th century

long before archeology had revealed the story of the Ice Age and

aftermath or N-haplogroup genetics. The Finno-Ugric languages are

best viewed as the result of boat people expansion from 10,000 years

ago to about 8,000 years ago, followed by the establishing of dialects

within the four major water systems. Since the Samoyeds do not

belong in this group. and there is no tight Ural Mountains origins, the

term "Uralic" is no longer appropriate. The best is to speak of

"Finno-Ugric" and "Samoyedic" separately and allow the "Finno-Ugric"

origins to be in the east with the "Finnic" ("Ur-Finnic")

The

Emergence and Expansion of Water

People

THE MELTING GLACIERS CREATE A WATERY LAND :

"UIRALA"

At the peak of the Ice Age, the glaciers

descended to the central part of continental Europe. Geologists tell us

that as the glaciers developed they drew water out of the oceans and

lowered the sea level. When the climate began to warm, when the Ice Age

receded, when the glaciers melted, the sea level did not rise

immediately because the glacial meltwater first spilled into the land

and inland seas and it would take some time for the water to flow to

the sea and raise its level back up. Thus there was a period of time

during

which the lands below the glaciers were inundated, and any hunters

found there would have no choice but to develop ways to travel on

water. Gradually they adapted and soon they had access to a rich bounty

of fish, sea-mammals, and waterfowl, not to mention animals that like

water like the "moose" (American English) or "elk" (British English).

Paleoclimatologists tell us additionally that the

Ice Age receded initially slowly, and then accelerated. For 10,000

years climatic change was barely perceptible, but then around

10,000-6000BC the warming was very fast. The reason for this is that

when most of Europe was covered with glaciers, its white color

reflected the sun's rays back into space. But as the melting progressed

and the dark colors of the earth were exposed, less sunlight was

reflected back into space, and the heat gain of the earth accelerated,

causing the glaciers to melt faster and faster until in the very last

stages everywhere the land was warming and the glaciers were depositing

their water. Water was being dumped far more quickly than it could

drain to the oceans. It was a very wet land, but the boat-using

hunter-fisher-gatherers flourished, probably more than any other

people. It an be argued that the boat-people became the dominant group

in Europe. I call their watery world UI-RA-LA. It's peak of expansion

was at about 8000 years ago. Then climatic warming slowed down

again, the glaciers disappeared, water flowed into the sea,

and things stabilized in subequent millenia.

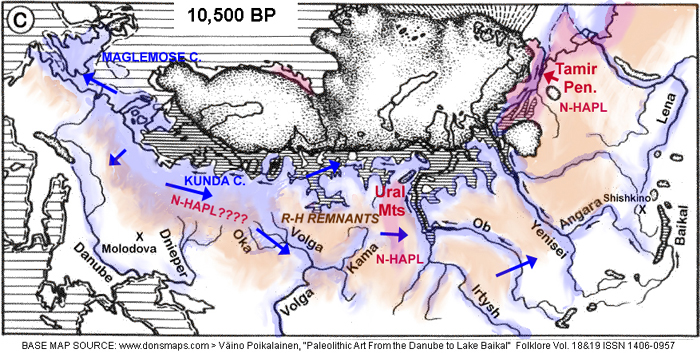

From the Preface, I show the following map of the

region around the rise of boat peoples at the time of maximum warmth.

FIG 2.

The

blue tone and blue arrows represent the initial expansion of the boat

peoples. The pink tone represents actual surviving reindeer hunters and

herds. The orange tone represents former reindeer hunters left in an

open subarctic landscape who had to hunt other animals like moose and

move around on foot as before. The boat peoples was one of the

adaptations that was very successful. Less successful solutions to the

loss of reindeer herds and the warm climate would have borrowed boat

use, just as later in history, people borrowed farming practices. Once

invented and mastered, anyone could copy.

A WAY

OF LIFE INVOLVING BOATS

Today we take the use of boats for granted.

Because today anyone can purchase a boat and go fishing,

there is a

common belief that boats and boat use is something that could easily

arise from simply concieving of it and trying it. For example,

some scholars have said the idea for a skin boat could come from

watching a wicker basket float on water. But such experiments and ideas

are what humans do all the time - they are just amusements or toys. Or

they could be ad hoc contrivances to solve a one-time problem. The idea

is never adopted into common practical uses because there is no real

long term necessity.or usefulness for it.

Indeed, humans have always been

able to

put baskets in water and watch them float. Children can even climb in

them and play games. Another good example would be to

ride

on the back of a large animal. There is not doubt that early horse

hunters may have developed a sport of jumping on the back of the wild

horses and trying to see who could remain on the longest. But games,

amusements.or sport

would not become

established in that society until this practice of riding on a horse's

back became useful in the

way of life in general.

Another example would be the discovery of

electricity. Apparently a battery had been invented in ancient times,

but it was used probably as a novelty of some kind. It was a toy. Who

back then

could have imagined that one day there would be a world society that

actually ran on electricity?

The reality is that an idea does not become

established in a society unless

it is truly necessary and economically viable. The invention of

boats

had to represent improvements for a society that offset the natural

reluctance of the human being to take to water. The use of boats or

water craft like rafts were probably used by humans maybe back to ape

ancestors, since today we can see apes devising ways of crossing a

river on something serving as a raft. But these are one-time

solutions to challenges, and not something of continual necessity.

Indeed, the reindeer hunters from which the Maglemose and Kunda

cultures emerged had probably created ad hoc watercraft to ambush

reindeer crossing a river, the river slowing them down. The story of

the boat people is not the invention of the boat, just as horseback

riding is not the invention of it for a particular purpose, nor how

weeding around wild berry plants is farming. What we must see is

the practice becoming a central necessity in the way of life. Unless

you find yourself living in swamps, a boat is just a novelty or an

occasional practical device. Unless you live in open steppes, horseback

riding is an occasional practice. Unless you live in a location where

wild food cannot grow, farming is an occasional practice too.

At the origin of boats

you really needed a situation in which

humans needed to deal with flooded lands all the time, generation after

generation. Beginning with the need to cross waters to get from one

island region to

another, soon they found they could just as well hunt and gather water

animals and plants as well. This then promoted improvements to the

dugouts and the invention of new hunting practices that employed boats.

Once the

art and technology of using dugout canoes had developed not

only did it open up opportunities to hunt and gather in watery

environments, but the boat actually allowed them to travel some five

times faster than even walking on clear solid ground. The degree to

which the boat people recieved benefits can be the equivalent of the

later advantages of farming. Today's culture of automobiles on

highways, is based on an older one of horsedrawn carriages on roads,

but both are ultimately based on the oldest tradition in transportation

- boats on rivers. Without the boat-oriented way of life, and the

results in shipping and transportation, Europe today would not be much

more advanced as as large scale civilization than North America in the

17th century before European colonization.

ONCE

ESTABLISHED, AND PERFECTED, NO STOPPING IT.

Starting new inventions and new ways of life

using them, is very

difficult - there have to be sustained environmental pressures, and

there has to

be a long evolution from crude actions to a refined way of life.

That could take many generations.

But once the way of life has matured

and proves to be successful then other peoples can quickly copy it. Not

only does the establishing of it validate it for others to copy, but

new users do not need to progress through a long evolution anymore. By

simply copying, they derive the benefits immediately.

The development of horseback riding too, may

have taken a hundred generations to develop into a central role in a

society, but once it was established all other peoples could adopt

it. But it had to begin in a slow way accompanied by sustained

pressure.

With the

success in hunting and gathering, and travelling between bountiful

sites, it is no wonder that the populations of boat peoples blossomed

and caused tribes to divide and divide producing new tribes who

travelled further and further away to occupy the still-vacant coasts of

lakes, rivers, marshes and bogs from Britain to the Urals. It all makes

sense. The growth of populations of boat peoples probably

exceeded the

growth of any other post-glacial hunting people, and such growth

probably did not occur again until civilizations developed in southeast

Europe. In other words, a great portion of humanity today has the boat

people

at their roots. It would explain our love for recreational boating,

canoing, and fishing. Recreational activity tends to be connected to

ancient experiences that have found themselves into our human nature.

A Finnish linguist, Kalevi Wiik, a couple

decades ago, proposed that northern Europe originally spoke "Uralic"

(of which Finno-Ugric is the largest division). If the original boat

peoples arose from European reindeer peoples, and if after the

development of the use of boats, they expanded in every direction from

their north European origins, then indeed, before the development of

farming-based Europe, before the arrival of Indo-Europeans, northern

Europe could very well have spoken Finno-Ugric as Wiik suggested,

including all regions later recieving the Indo-Europeans that gave rise

to Celts, Germanics, Slavs and Balts. Wiik tried, in his papers in the

2000's to imagine how the Finno-Ugric boat-using hunter-gatherers

responded to the immigrant peoples, from the farmers to the cattle

herders in those millenia between 10,000 years ago and about 5,000 or

4,000 years ago. That is about 5,000 years of the original hunter

gatherer peoples with boats, north of the Alps, interracting with and

adapting to the presence of newcomers.

NORTH

AMERICA

Could there have been an independent

development of boat people in North America? Unusual developments need

special circumstances and sustained pressures. Consider that North

America had some large animals that could

have been

domesticated. An elk or moose could have been developed for uses

similar to horses - but it didn't happen. And yet when the Plains

Natives saw Spaniards riding horses they were quick to copy them

and the North American Plains Natives were riding

on the backs of horses within a couple generations after seeing

Spaniards use them.

When we consider boats, archeology fails to find

evidence of boats in North America predating about 5000 years ago. It

seems that boats did not develop independently in North America -

the same environmental pressures never materialized - but were copied

when the first skin boats crossed the north Atlantic from the coasts of

Norway. Consider that the Atlantic coast of North America never saw the

development of boats made of planks. All North American boats

were either dugouts, or skin boats on frames, which includes using

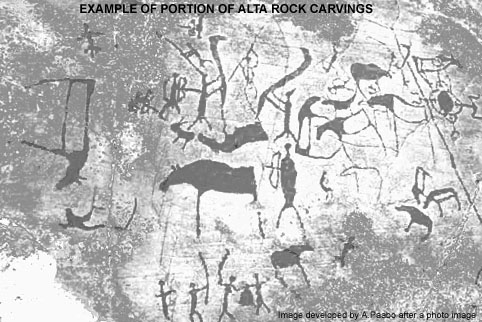

birch bark for skins. While northern Europe has rock carvings

dated to as much as 8000 years ago, showing both dugouts and skin

boats, all images in North America that show boats are relatively

recent.

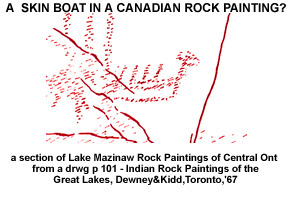

Finland has red ochre images on rock walls that were

originally beside water, and made from boats, but all the images are so

degenerated it is difficult to make them out. On the other hand similar

red ochre paintings on cliffs beside water in the Great Lakes of Canada

are fresh enough that you can tell what the images represent. They

suggest visits from the arctic coast of Norway by aboriginal people of

Finnic origins (since they carried out exactly the same practice as

found in Finland)

relatively recently. See another Uirala article for more on North

American mirroring of red ochre cliff art beside canoe routes.

Crossings of sea-hunting peoples took place as well,

as will be discussed in a later article. The Inuit of arctic North

America is an example. We will look at such aboriginal sea-hunting

peoples in Northern North America for evidence of a connection to the

boat peoples of northern Europe who became seagoing.

The Structure of

Hunter-gatherer Boat Peoples Way of Life

THE EXPANSIONS OF THE BOAT PEOPLES

Originally, boat use may

have developed simply to deal with the fact that land suitable for

walking had disappeared in the North European Plain between 13.000-

10,000 years ago; but once the boat had begun to develop, unexpectedly

it offered great additional benefits - access to water plants and

animals, and ease of travel.

At the same time, the warming climate was causing

the populations of wildlife to increase as well - the marshes came

alive with waterfowl, fish, and even large animals like the

moose. This new way of life using

boats was successful, and the boat-people populations began to increase

in

parallel to the wildlife. Bands and tribes grew large, and daughter

tribes split off from mother tribes, and migrated far enough away to

establish a new hunting-fishing-gathering territory.

It is necessary to understand a little about the

social organization of nomadic hunting peoples - how they expanded, how

they interracted. We can learn a great deal about it by what is known

about the Algonquian canoe-using hunter-fishers of the northeast

quadrant of North America. The most important truth for scholars

to understand is that humans are territorial. You simply cannot say

that a particular people migrated into another area, without

considering whether there were already people there. If there were,

intruders were resisted, told to move on. If they did not, there was a

battle for supremacy. Scholars cannot treat the environment

as if it were vacant - except in the beginning. The boat people

originally expanded into virgin lands, but once the expansion had been

completed and tribes were claiming ownership over wildlife in different

regions, newer immigrants had to deal with those who were already

there. The newcomers could move on, or agree to take marginal lands.

Thus while the original expansion could cover the entire region from

Britain to the Urals in 1000 years, further waves of migration had to

deal with the established peoples - taking marginal lands, fighting

battles over ownership, and trying to find peaceful ways of sharing

increasingly limited resources. Note that in civilization we think of

lands in terms of acreage for farming. Hunting peoples did not have a

sense of owning nature, but owning rights to hunt particular

animals. A farming people could move into the territories of a

hunting people as long as they did not hunt. This is something scholars

do not understand. I recently read of how scholars studying the early

peoples of central Europe were puzzled that the hunting peoples did not

adopt anything from the farming people in spire of contact. Partly this

indicates a continued racism, where it is expected that aboriginal

people ought to want to become farmers. But mostly it is because

scholars do not understand that peaceful co-existence of two different

peoples requires that each side remains within their own economic

territory. It is interesting to note too that in Canada, the farming

natives known as "Hurons" were 90% dependent on what they farmed -

maize, squash, etc. They could have hunted and fished but they

were closely involved with the Algonquians - the seasonally nomadic

hunters-fishers. If they wanted meat, it would be more likely from

trade - meat for maize. If the Algonquians did not live in the same

environment, the Hurons would have been more involved with

hunting and fishing. Different peoples could occupy the same landscape,

as long as they exploited different resources. In other words concepts

of territory could overlap in the same landscape. Farmers,

traders, fishermen, crafters could - and later did - occupy the same

environment as long as they were clear as to staying within their

territories and respecting those of the others. It is the origins of

professions. Specialization plus trade also made for a better economy

for everyone involved.

The nature of hunting-gathering societies is clear

from what was observed of the North American Algonquins before the

arrival of Europeans disrupted them The organization of

hunting-gathering society is not designed by anyone, but the

consequence of human nature and necessity within a particular way of

life. In the basic aboriginal society humans

form bands, extended families of brothers and sisters, children and

elders, who then move together through a territory. But bands can meet

up with

bands, to form tribes. Evidence suggests that an average natural tribe

had about 5-7 bands.Anything larger was difficult to maintain, without

some organization. The pattern of life of nomadic

hunter-fisher-gatherers is that every band moved around in their band

territory throughout the year, but annually 5-7 bands would meet at a

central location to socialize, trade, mate, and generally reaffirm a

larger tribal social order. Thus the region of linguistic and cultural

uniformity extended over the total area of the movements of all the

clans of the tribe. Sometimes two or three neighbouring

tribes would congregate in larger festivals, and that would counteract

the development of dialects between one tribe and the next. If the

territory covered by a band of boat-using hunter-fisher-gatherers was

large, then areas of linguistic and cultural uniformity could be very

large, much larger than is commonly assumed.

THE LARGE SIZE OF BOAT-PEOPLE TERRITORIES

An important and also unrecognized

aspect of the boat-peoples is that with boats, boat-using

hunter-fisher-gatherers could travel over five times faster and farther

than the earlier hunters that moved on foot over clear open land. That

means boat-using hunting-fishing-gathering territories could be over

five times larger than that of the earlier big animal hunters, like the

reindeer hunters. For example, if a reindeer hunter band covered a

territory 100km in diameter, the boat-users could cover a territory of

500km in diameter with the same effort. Furthermore, since boat-use was

determined by the

nature of the waterways, their territories would be stretched in

various ways. A linear territory could assume the form of travelling

1500km up and down a river, or along a coast. (For example, evidence of

rock carvings with moosehead skin boats suggests that there may have

been a tribe that migrated annually between wintering at Lake Onega and

summering in the islands off the coast of arctic Norway. Lake Onega

images of moose do not show antlers - proof that these people were not

there in summer and never experienced antlered moose (antlers are lost

in the fall and regrown in spring).

TerrItory is very important in the human

psyche, and it follows that if the range of tribes with boats was this

large, then in the early period of expansion of the boat peoples, it is

clear that breakaway bands and then tribes would have to travel a great

distance

to remove themselves from the territories claimed by the parent band.

If families were having three children, then a breakway tribe would

form every 50 years or less, and move about 500km away. They could

expand 1000km in every century (The destination lands have to be

unoccupied, as mentioned above for that speed) The most recent example

of rapid

expansion of a boat-people is that of the Canadian arctic "Thule"

culture from Alaska to Greenland in only about 500 years.

As I mentioned above, the original

expansion (10,000 to 6000 BP) the expansion was unopposed. Before

the boat peoples there were

no previous peoples across the subarctic forest zone of Europe. Before

the evolution of boat-peoples the

water-filled forests south of the tundra were unoccupied. The only

people they might have encountered were the reindeer-hunters. But the

reindeer hunters were above the tree

line and moved around on foot, therefore they were rarely found in the

niche into which the boat-people expanded. In a sentence--the

boat-peoples were unopposed and for that reason the expansion was fast!

They did not have to displace any earlier

peoples. They did not have to battle with people already there.

This is something that we cannot understand

today. For several millenia now, any immigrant had to deal with

the people already established in a location. The days of simply moving

into virgin lands, and occupying them, has long

disappeared. Either the immigrants have to negotiate with

those already there, or come with an army and conquer them.

THE

PATTERNS OF EXPANSION

As already noted, because the

territories of boat people were large, when populations grew and tribes

formed out of parent tribes, the new tribes needed to travel far enough

away so as not to overlap the parental territory. That meant moving out

of the parental water basin into a new one. The entire region between

Britain and the Urals could have been filled in less than 1000 years.

Thereafter there would have been internal dynamics until territorial

stability was achieved -- everyone knew what regions belonged to what

clans and tribes.

A natural human tribe consists of 5-7 bands

(extended families of brothers and sisters, their children and elders).

(Larger tribes require political organization, government, to remain as

one.) From the Canadian evidence, the most common pattern among

boat-peoples is that the 5-7 bands each owned one of the water basins

of the tributaries of a large river so that the tribe as a whole owned

the entire river water basin. The bands travelled through their large

territories on their own for most of the year, and then they all came

together once a year to socialize, find mates, trade, exchange news.

The tribal meeting place was usually near the mouth of a river.

In the case of peoples who fished and

hunted sea coasts, perhaps a tribe was distributed along the coast,

each band claiming a part of the coast. Archeology shows that there was

a cultural unity along the south Baltic which they have named

"Maglemose". If the bands of this tribe travelled the coast, the

central location where the bands got together would have been at the

mouth of the Oder as it would be a central location. And on the east

Baltic the bands of the tribe archeologists have called "Kunda" would

probably have met at the Dvina (Daugava, Väina) at the Gulf of Riga.

The mouth of the Vistula would have been the gathering place of bands

who travelled the Vistula. If the three tribes wanted to meet in a

large gathering, the mouth of the Vistula was a good place. Archeology

has found overlapping of archeological cultures there. Another location

where it appears two or three tribes came together is Lake Onega.

These patterns are illustrated in the information

box below:

CANADIAN MODELS OF BOAT-PEOPLE BEHAVIOUR

There is no need to guess at the behaviour of

canoe-using aboriginal hunters in Greater Europe because proof

can be found in the traditions of

boat-using hunter-fisher-gatherers of Canada.

The further north the

people live, the lower the food density in the land, and the further

they had to travel to secure their food. Thus for example the Cree

around forested part of the the lower Hudson Bay, covered a territory

as much as 3000km wide, their far-ranging movements keeping the

language from breaking into many separate languages over that entire

area. (Europeans did however note three dialects). North of them, the

arctic ocean boat-oriented Inuit had established a single language,

with about three dialects from Alaska all the way to Greenland.

Towards the south, where food density

was greater, people did not have to travel as far. Shorter-range

interaction between peoples caused dialects over smaller regions and

for there to be suffiencient separation between the larger groups as to

develop distinct

languages (=dialects that are too far apart to be easily understood by

each other). For example in Canada, the Ojibwa boat-people lived

throughout the Great Lakes water basin, the Algonquins in the Ottawa

River water basin, the Montagnais Innu in the Saguenay River water

basin, the Labrador Innu in the Churchill River water basin. Note how

water basins defined the regions, since boat-use was generally confined

to the water basin. Within these divisions there were dialects too,

especially among the Ojibwa. To be accurate, the language varied in

relation to distance, and while adjacent tribes could understand each

other's dialect more distant ones had difficulty. Linguists

unfortunately do not think in terms of continua of language where

distinct languages only occurred where there was some kind of barrier

to communication. For example in the east Baltic coast, there would

have been a continuum of dialects up the east Baltic coast, but then

because of the obstacle of the Gulf of Finland, a dramatic difference

between the north and south side - the reason Estonian and Finnish are

considered distinct languages, while southern Estonian dialects would

have transitioned into the northern Livonian dialects, Livonian into

Curonian, and so on. In North America, it would have been

similar - the strong differentiation being caused by geographic

barriers or some other basis for separation. For example the Montagnais

Innu lived on the Saguenay River, so they would have to be different

from the Algonqjuins on the Ottawa River.

Once we understand the way the North American

Algonquian boat peoples divided up their activities in the Canadian

landscape we get to understand the early situation in ancient Greater

Europe very well. Notably we can predict that the Ob, Kama, Volga

Rivers (for example) would produce separations that would promote all

their languages drifting apart from a common parent. Thus once we

identify the early Finno-Ugric cultures as aboriginal boat peoples like

the recent Algonquians we can predict that linguists will find

linguistic differences according to the major water systems. Indeed,

that is what they found - the Ob-Ugrian languages on the Ob River, the

Permian in the Kama River water system, the Volgic in the Volga, and

the Finnic in the waters draining into the upper Baltic. It follows

obviously that if the expansion from the "Maglemose" culture of the

Jutland Peninsula (Denmark) is correct, then not very long ago there

must have been more Finno-Ugric families - perhaps a family on the

Vistula, perhaps descendants of "Maglemose" on the Oder, perhaps a

family in southern Sweden, perhaps even a Finno-Ugric family in

Britain. Such notions are controversial to everyone who has

fallen victim to the erroneous theory of migrations described

above.

The most primitive way of life among surviving

Finno-Ugric cultures are also the most remote - the Ob-Ugrians on the

Ob River which drains into the arctic ocean east of the Ural

Mountains. Even recently clans went up the river to spend part of

the year in their traditional campsites. They have been documented by

the films of Lennart Meri shot in the 1980's. The films include so many

primitive aspects that when I showed it to an Ojibwa friend in Canada,

he initially thought it was all staged and everyone was acting.

The film included icons familiar in Algonquian culture such as

the drum made by stretching skin on a frame, and the teepee

construction.

Most notable about the Ob-Ugrians is that they were

still continuing a tradition - the tradition of a tribe occupying a

whole river, each extended family possessing a branch of the

river, and all the bands congregating near the mouth to affirm the

tribe. (Of course today, the practice has degenerated, but at least the

essence of it still remains in the practice of clans to go upriver to

traditional camps.)

And the territories of the ancient tribes

could be enormous. In North America the Montagnais Innu occupied the

whole Saguenay River system. About the time the French first arrived,

they came down to the mouth and congregated to affirm the tribe. The

location was called Toudessac. Interestingly, when Europeans

began arriving in ships it was the Montegnais who set up a trading post

to trade with the Europeans.

In Eurasia the Khanti were equally enterprising.

Learning of places to trade at the southern reaches of the Ob, groups

made long trips southward to engage in trade. The Ob River is

very large and in effect the Khanti occupied a territory as large

as all of eastern Europe! We only need to project what is

relatively recent in the Ob River to large rivers to the east. For

example, it is easy to imagine that when agricultural people arrived

(The Danubian Culture) it was not the agricultural people who travelled

down the Danube to trade at the eastern Mediterranean or Black Sea. It

would have been descendants of the boat peoples. Similarly other

rivers would have seen the boat people easily assuming roles as

traders. We can easily imagine situations in the Vistula, Dneiper,

Oder, Rhine, Volga, etc.

where one subdivision of the boat-people dominated an entire water

basin.

The following map depicts actual archeological

discoveries of "archeological dialects" among the ancient peoples who

were all essentially dugout or skin boat users. The graphically

patterned areas represent locations where remains of a particular

"culture" have been found. The map described the period of

between 7500-3000BC or 9500-5000 BP (before present). This is the

period of boat-peoples expansion. Note the hatched area at the bottom.

At that time it would have represented a culture that lay in the

Vistula water system and upper Oder. Note also another hatching for the

Dneiper. Later archeology reveals the entry of agricultural peoples in

these areas, but that may be misleading. Boat peoples and agricultural

peoples can coexist as they do not interfere with each other's sense of

territory. Moreover people tied to settlements and farm fields would

welcome the service that the nomadic boat peoples offered, such as

trade. Here too there are models in recent North America, in the

relationship between the farming Indians, the Hurons, and the

seasonally nomadic boat/canoe peoples, the Algonqians.

THE

OCEANIC TRIBES PATTERNS ("Komsa", "Fosna")

The patterns followed by oceanic hunters are

more mysterious. They may not even have had annual cycles, only meeting

other bands every five years or so. The Shetland Islands lore speaks of

a people they called "Finns" who were estabished for a few years on its

northern islands, and then disappeared.

Existing Shetland traditions speak of

a people called Finns

who inhabited Fetlar and northwest Unst for some time after the Norse

occupied Shetland. This name is identical with the one by which the

Norse knew the aboriginals of northern Scandinavia. It was aso the name

given by Shetlanders (of Norse lineage) to a scattering of Inuit [?]

who, in kayaks, materialized amongst the Northern Isles during the

eighteenth century. . . .In any event, Shetlanders used the same name

for these small-statured, dark skinned strangers that their ancestors

had given to the people who preceded the Norse in Shetland. (F. Mowat, Farfarers, Toronto 1998)

Farley Mowat, quoted above, advanced a theory

that original British who he called "Albans" endured in the Northern

Isles, and hunted walrus, travelling all the way to the coast of

Canada. In my theory there were always two types of boat-peoples in the

British Isles, the original dugout-using interior hunter-gatherers who

were orientated towards the east, became traders, and the skin-boat

oceanic hunters that came down at an early time from the arctic

Norwegian coast, and always remained sea-hunters, much like the Basques

further south.

If there was a circling ocean current, like

there was north of arctic Norway, and also between Norway, Greenland,

and Iceland, the movements of the oceanic hunters might have gone with

the current. The collective tribal meeting place would be in the

mid-point somewhere. For example the location where the "Komsa" culture

settlement was found, in north central Norway, would be on the edge of

a cycling current.

The evolution of oceanic tribes and ocean

expansion will be described further later.

THE

SEQUENCE OF EVENTS SINCE THE ICE AGE

In the prehistoric beginnings, as the great

ice sheets of the Ice Age retreated, populations would

have continued to grow as long as the climate was warming. When the

glacier, which was centered on the mountains of Norway became small,

climate change had slowed down. The populations of boat peoples

stabilized. They had expanded as far as nature allowed, and now they

settled each into their water basins, and each tribe started to

dialectically change within their territories because there was little

communication across water basins. These small changes are reflected in

archeology.

We know that boat people went into the

Volga, because three of the Finno-Ugric language families are accessed

by getting onto the Volga. What is unknown is the situation in the

Dneiper and other rivers draining to the Black Sea from the Baltic

direction. Languages originally there have vanished.

Map 2: Boat Peoples Are

Partitioned By Water Systems

This map, based on geography of

rivers, roughly suggests regions where water systems tie tribes

together. The main criteria is rivers flowing in the same direction

towards a sea. This information is important in understanding how

languages and archeological data changes. The coastlines and

river orientations also suggest the directions of expansion of

boat-using peoples.

Map 2: Boat Peoples Are

Partitioned By Water Systems

This map, based on geography of

rivers, roughly suggests regions where water systems tie tribes

together. The main criteria is rivers flowing in the same direction

towards a sea. This information is important in understanding how

languages and archeological data changes. The coastlines and

river orientations also suggest the directions of expansion of

boat-using peoples.

As I said above, while humans could devise a raft of

some kind probably

even 50,000 years ago, they were basically land-people and the

development of the design of the boat, the manner in which one

travelled and hunted, etc had to be a slow process. It may have taken

1000 years or more to refine the dugout boat, determine what to hunt

and fish, develop new tools and techniques, etc. Those that had better

ideas were more successful. It was thus Nature that gradually selected

the people and methods that worked best. More successful methods

resulted in more children, more population growth, more expansion. We

must not picture a sudden invention of boat use, and a sudden

expansion. It could have, by chance, begun in one place, and

expanded from there.

The population growth in the beginning

when the people had

not figured out their new boat-oriented way of life was probably nil,

then as their methods improved there was slow population growth and

then a faster one, until the boat-culture had reached its final optimum

form. For example early dugout canoes were probably crude cavities in

logs, but in the end they were the sleek, thin-hulled, designs such as

are still created by the Khanti on the Ob River. Once the boat was

developed, it could endure by imitation. It is far easier to imitate

than originate. (In the world of art, any capable artist can make a

copy of the Mona Lisa, but only Leonardo da Vinci created the original.)

It would have been a process that took

at least 1000 years, probably 2000. Perhaps the crudest boat people,

making only a hole in a log, and stumbling about as best they could,

began in 10,000BC. Perhaps it wasn't until about 8,000BC that the new

way of life in a watery landscape had reached maturity and dramatic

expansion began.

The idea that a boat-culture does not

happen unless Nature imposes pressures forcing humans to make it

happen, or that it does not happen overnight, leads us to ask whether

boat peoples in other parts of the world were independent evolutions,

or whether they all acquired the basic culture from the boat people

under the north European glaciers. We have already touched on this

earlier. Since humans are land-creatures, the development of a

boat-oriented way of life required strong pressures to force humans to

act against their instincts.

I have referred to the Inuit (Eskimo) of

arctic Canada. Their boats were made of skins and included a one-person

craft called a kayak and the other a large vessel that would carry an

entire clan, called an umiak. To their south in the subarctic forests

there were the Algonquian boat-using hunter-fisher-gatherers who

travelled up and down the rivers. They included Cree, Ojibwa,

Algonquin, Montagnais, Innu, etc. Their boats were made by covering a

frame with birch bark. The birch bark canoe can be viewed as a form of

skin boat. Algonquian peoples towards the south along the Atlantic

coast also demonstrated dugout canoes and skin boats using moose-hide.

Were these boats independently developed or did the prototypes come

across the North Atlantic? There are many similarities between the

culture of the Algonquians and what is found in Finno-Ugrians. This

question calls for further discussion in another article.

Skin Boats and

the Oceanic Boat People

Since humans were not naturally inclined to live on

open water, I believe that boat people began as the dugout peoples who

stayed close to coasts and within rivers and marshes. Peoples who

sailed into the oceans and seas

developed a little later. For example evidence of boat-people off the

coasts of arctic Norway, does not really appear until about 4000BC.

Currently archeologists have rationalized that they came there by

coming up the Norwegian coast. By why would they travel north in ocean

waves along a forbidding shore with glaciers in the distance, when

there were plenty better places to go? This and other similar common

sense arguments suggest that the original sea-hunters of the Norwegian

coast came from the east, via arctic Norway. See MAP 2 which shows how

the regions around the White Sea and Kola Peninsula were ice-free. What

group of people would have travelled north along a glacier coast, with

nowhere to land?!

Once the sea-hunters were

estabished in arctic Norway, and the glaciers had exposed the shore,

approaches were also possible from the south. We are here

interested in the beginnings. If we consider the beginnings, that is

the first boat-peoples in the Norwegian arctic, then we have to

conclude they came from the east over top of Norway, from around the

White Sea. Then that opens another question - how did they get to the

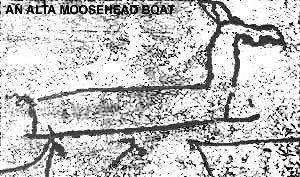

White Sea? The answer is clear in the rock carvings at Lake Onega. They

show a skin boat made of moose hide, with the head on the prow. Rock

carvings in arctic Norway include examples of exactly the same boat-

with moosehead. Since moose does not live in the arctic, the people who

used them must have originally travelled to the arctic coast from

someplace towards the south.

The next question is, how did they get to Lake Onega?

There are many reasons to believe that

oceanic hunters of arctic Norway originated from the east, from the

White Sea, and Lake Onega. Humans do not adapt to

something that is as unnatural as dealing with the open sea very

easily. There had to be strong

pressures forcing boat people to take into open ocean waves. Such

pressures would have existed in the north where food density was low.

Thus, I believe that the original

boat-people on the coast of arctic Norway came by way of the White Sea

in skin boats. Rock carvings found at the Norwegian island of Sørøya,

show images of a light dugout, too small for ocean waves, but also a

high-prowed vessel with a moose-head prow ("moose" is an American word

of Algonquian origin for what is "elk" in British English). I believe

that this moose-head boat was a skin boat made from the full hide of a

moose, slit along the back, frame inserted, leaving the head attached

for spiritual reasons. These people obviousy also had dugouts, but,

like the Khanti dugouts, were too small to navigate in open seas.

Possibly the Inuit kayak , which enclosed the top to allow waves to

break over the top,

was in effect an adaptation of the tiny one-person northern dugout, to

deal with high waves and could be built without need for any tree.

If the boat was made of a moose hide, it

meant the people had to winter in a place with moose, in the forested

zone. It is common sense that since the arctic was cold and dark in the

winter, early visitors

to the arctic did not stay there through the dark winter. They all

returned to a more southern place. Lake Onega was an ideal wintering

place for boat people dealing with the White Sea and beyond. It was

also a place to hunt moose and make more boats.

It is therefore significant that rock carvings

of the very same small-size moose-head boat that was found in arctic

Norway at the island of Sørøya has been known for a long time at the

famous carvings at Lake Onega. See information box below:

What is peculiar is that some of the rock

carving images at Lake Onega

show

sea-harvesting activity that would only occur in the arctic ocean, not

at Lake Onega, as if they

were picturing last summer's activities.

One

image, for example shows the catching of a seal. Meanwhile, the

Sørøya carvings show images of forest animals, as if when there, they

reminisced about their other home, their winter home.

Archeologists have puzzled why the Sørøya carvings do not show their

activities at that location, but forest animals - the answer is

obvious: homesickness. They must have divided their time between

summering on the arctic Norwegian coast and wintering in the forests

such as at Lake Onega.

In the annual cycle of nomadic

hunters, entire

bands, including women and children, moved together from camp to camp

and they did not have to return to the same place until the next year

(or whatever the length of their nomadic circuit.) Thus they could all

move six months away from their wintering location, and six months

back. In actual fact, the time distance from Lake Onega to the warm

waters of the Atlantic Drift, was about a month or so. We cannot

underestimate the distances humans will travel on the ocean,

considering that in the 16th century Basque whalers were regularly

crossing the Atlantic in sailing ships to harvest whales off the

Canadian coast.

The next stage in the evolution would obviously be

that some groups decided not to go back into the forest, but to remain

in the north, biding their time in the dark until the sun returned.

This would have been possible if they had caught enough meat to store

for winter use. In the winter it would not spoil. They may also have

interracted with interior reindeer people and copied their ways of

dealing with the dark winter. It is this interraction that from both

intermarriage and cultural sharing, I believe produced the Saami

- linguistically Finnic, but displaying genetic roots (esp among women)

from the east (ie the Samoyeds), and reindeer harvesting practices.

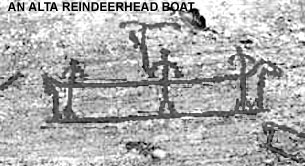

Those who thus remained in the north -

producing the archeological "Komsa" culture - were lacking moose in

their environment, and they now made skin boats

from reindeer or walrus hides. The moosehead disappeared from the skin

boat, replaced by either the reindeer head (as seen in Alta, Norway

rock carvings) nor walrus head (something found in the traditional

Alaska Inuit large skin boat called the umiak)

These people, no longer returning to the White

Sea or

Lake Onega area, with success and population growth, were able to

migrate further in search of new

sea-hunting places. Some breakaways, would have migrated south to the

outer islands of Britain becoming ancestral to the seagoing "Picts" who

history

records having skin boats. (We must not confuse the aboriginal short,

seagoing "Picts" with the "Picts" history defined as peoples settled in

northern British Isles before the Celts arrived who were probably

original British from the dugout traditions.

The eastern and interior parts of Britain

would already have been established with the original dugout-boat

peoples and traditions, but the seas had until that time been an empty

niche.

After the skin boat seafarers, the "Finns",

had spread through the outer and western parts of

Britain to harvest a branch of the Atlantic Drift that turned towards

the northern Isles, then perhaps some migrated further south, possibly

ending up as far

south as Portugal, possibly inspiring the legends of "Atlantis". They

would have become the founders of the Atlantic "Megalithic" culture, a

culture that built hill-tombs and alignments of large rocks not far

from the coast (meaning they were a people who followed coasts). The

"Megalithic" culture, as some scholars have called it, gradually spread

up the western European rivers establishing the culture throughout

western Europe. The key question as to where the migrations went

relates to the ocean currents and sea-life they harvested. In the

north, the bountiful places were located where the North Atlantic Drift

(originating on the American side as the Gulf Stream) came up to the

west of Britain, past the northern Isles, with a branch turning

eastward between the northern Isles. This ocean current then

headed towards arctic Norway, passing the Lofoten Islands, and into the

Norwegian arctic islands.

No oceanic peoples did not wander just anywhere.

Therefore one must wonder what reasons they would have had to go south

along the Atlantic coast of Europe. There are two answers - a whaling

people who followed whale migrations south, or eel harvesting people.

Eels originated in the Sargasso Sea and crossed the Atlantic, and

migrated through the North Sea and the Strait of Gibraltar. Where there

was a bottleneck, the eels were plentiful. Another bottleneck was at

the Jutland Peninsula. It is thus possible that the fabled

Atantians were "Eel People" and may have had early contact with the

Americas via a route similar to the one followed by Columbus. Even

though the "Atlantian" story is speculative, the oceanic sea people in

the British Isles, and the archeological evidence of a "Megaltic"

culture on the Atlantic coast from Portugal to the northern Isles of

Britain, and even as far east as the Jutland Peninsula, tends to

support a theory that there were an "Eel People". But this would

date back to as much as 6000-4000 years ago. (They could also

have originated out of dugout peoples just as well.)

The story is clearer about the others of the arctic

Norwegian

sea-hunter traditions, who migrated across to Greenland and Iceland and

further, becoming the archeological "Dorset" culture of the Canadian

east arctic. Canadian archeology reveals the "Dorset" culture has

affinities with northern Norway archeological culture, and had expanded

east-to-west across the Canadian arctic reaching the location where

later a "Thule" culture started coming back the other way. (Was "Thule"

ethnically a daughter to "Dorset" or the original White Sea culture

coming to the Canadian arctic having travelled in the other direction

over top of Siberia?) The "Dorset" culture appeared around 3500 BC,

which coincides with the time of the "Komsa" culture that stayed in the

Norwegian

north instead of migrating north-south. Conclusion: The "Dorset"

culture arose from the "Komsa" culture of arctic Norway.

It is reasonable to assume that the earliest

migrations were current-dependent. Reading the currents would let them

navigate well and less effort was needed. Knowing the currents, if they

did nothing but drift,

they would end up back in familiar territory. Later sailing away from

the currents

complicated matters, because the sailors were now departing from the

rock solid patterns of ocean current, and dealing with less certain

behaviours of the wind. For that it was necessary to develop

navigations skills that ascertained position with the help of counting

the days and looking at the sky. That came later. The following map

shows the manner in which oceanic peoples would have spread from the

White Sea area, westward over top of Scandinavia and then, with

success, continuing into empty niches in the ocean. As in the case of

the expansion of the original dugout boats, we assume that initially

the oceanic environment originally has no humans, so that expansion

from the arctic Norway region is unopposed.

Map

3. Suggested Groupings of Boat Peoples

The map above

develops further from the previous map which depicted the initial

expansion of the dugout boat peoples. This map primarily adds the

expansion of oceanic people using seaworthy skin boats (lighter blue).

It also proposes some specific zones of the original boat peoples. Some

explanation is needed: "Brito-Belgic" refers to boat peoples around the

coast of the North Sea and into the Rhine. The gathering place for this

tribe would have been the Rhine; "Suevo-Aestic" refers to the south

Baltic zone, that in later history was occupied by the tribes the

Romans called Suebi or Suevi, and the Aestii of the eastern coast (both

of which were originally Finnic). Their major congregating site for

them was at

the mouth of the Vistula. Archeologically speaking, the Maglemose

culture, associated with the earliest boat peoples, would include both

the "Brito-Belgic" and "Suevo-Aestic" zones. Archeological study would

also identify a "Volgic" group, whose extent reached up to Lake Onega,

and interracted with the Finnic groups at Lake Onega. (Interraction of

several cultures is evidences by overlap of artifacts in the same

area.) Archeology has also confirmed a "Megalithic" culture that went

from Portugal, up to the British Isles and by 2000BC also across to

northern Denmark. The only speculative detail in the map is the choice

of calling the people who occupied rivers that drained from the north

down into the Black Sea as "Venedic". See the next section for some

comments about "Venetic" traders that developed from boat people

exploiting their familiarity with boat travel for trading purposes.

The evidence that the main base for the expansion of

oceanic boat peoples was at Alta, Norway, is indicated by a great

abundance of

rock carvings have been found there including images of men harvesting

the

sea in boats with both moose heads and reindeer heads. There are also

images of hunting reindeer from boats as they cross water.

This region

of Norway has been the traditional home of the "Finns" and northern

Norway was called "Finnmark" (just as the region Sweden claimed that

was inhabited still by natives, was called "Finnlanda") The term "Finn"

used in the Germanic languages of historic Norway and Sweden, was a

term that generally referred to the aboriginal peoples of Scandinavia.

This included people who hunted in forests, harvested the seas, and

tended to reindeer herds. The first two - the seacoast people and the

interior hunters - were truly of boat-people traditions. The third

group, the one who tended to reindeer herds and who today refer to

themselves as Saami are and were a little different, in that they were

not boat peoples. Indeed their reindeer-dependent culture obviously

originated from the same ancestal reindeer people as the Samoyeds

towards the east in arctic Russia. What happened? I think it is a very

simple matter. Originally arctic Scandinavia only had the reindeer

people in the interior, following their reindeer herds. And then around

6000 years ago, with the development of the skin boat, and the

discovery of

harvesting the ocean off arctic Norway, boat people moved in, first

staying seasonally, and then staying permanently (ie Komsa

Culture). A situation developed (looking at the Komsa situation),

in which sea-harvesting skin-boat people, were found along the coast,

and reindeer people in the interior. Because they each had different

ways of life, they were not competitive, and contacts would have

developed between the boat people and reindeer people as long as each

respected the other's sense of territory. In the large

spans of time, the two groups would have merged through intermarriage,

resulting in the Saami. The modern Saami clearly reflect their

mixed origins. On the one hand they maintain reindeer-management

traditions that are very ancient, and on the other hand, their

appearance is quite European now, and their language is so Finnic in

character that it has been included in the Finnic languages.

Unlike some scholars, I don't find the origins

of the Saami to be a particularly complicated problem. Common sense

says that originally there must have been reindeer hunters following

reindeer herds, who originated from the same stock as the Samoyeds to

the east who also still maintain reindeer. And then Finnic boat peoples

came up from the south, and eventually many stayed there, to intermarry

with reindeer hunters. This did not happen towards the east, in arctic

Russia, because the expansion of the Finnic skin-boat peoples was

biased in the westerly direction where the warming Atlantic current

nurtured an abundance of sea life in arctic Norway. However in the

east, when the boat peoples went north from the Volga into the Kama, it

is possible that there was intermarriage and cultural exchange there

too, with the reindeer hunters, but to a lesser extent, and the

Ob-Ugric languages may be more Samoyedic than Finnic.

Of particular interest is that geneticists have

found that the mtDNA

among the Saami, that is carried only along female lines appears to

have affinity with that in Samoyed women - which would be

consistent with the boat peoples males taking reindeer people women as

wives whereas the reverse (reindeer hunters taking boat-people wives)

would not be true. Reindeer people men might not find women who knew

how to clean fish to be very useful.

The Boat-People And Farmer/Herders

During the great expansion of boat peoples, all the

rivers that emptied

into the northern seas were highways that could be used to travel

into the interior of Europe. As the boat peoples paddled up the rivers,

the waterways became smaller, and soon they were prevented from

continuing where the creeks and springs were too small for boats.

Unless they wanted to drag heavy dugouts through the forest to the next

water system, they did not go further. However there were some places

where entering another water system that drained south was easily done

from the northern water basins. One example might be the transfer from

the Rhine to the Danube.

But the easiest southward flowing

waterway to enter from the north was probably the Dneiper. Rivers

draining into the Baltic and rivers draining into the Black Sea seem to

have shared source waters, the same marsh areas. Thus it is valid to

propose that the boat people originally occupied the entire region from

the Baltic to the Black Sea (shown in Map 3 as "Venetic") Note that the

Dneiper and rivers like the Bug and Dneister, all flowed to the Black

Sea. One of the implications of this is that boat-people on these

rivers were most inclined of all of the boat people to make contact

with the farmer-herder peoples and their civilizations in the south

around the Black Sea. For this reason, I believe that they were the

origins of the Venedi/Veneti

who appear in Homer's Iliad as the "Eneti

of Paphlagonia", the region on the south coast of the Black Sea, on the

west side. They came to the aid of Troy. Troy's location at the entry

to the ancient Hellespont by which ships sailed from the Mediterranean

to the Black Sea, is good reason for coming to its aid, if the Eneti

were traders.

It is because boat-people in the Dneiper, Bug,

and Dneister had easy access to the Black Sea area and the developing

farming civilizations there, that I have covered these river water

basins with the "Venedi" designation in the above map. Volga too was

used for trade: the Volga flowed into the Caspian Sea but one could get

from the Volga to the Black Sea. as well.

Obviously, southward travelling boat

people encountered land-people in the south engaged in farming

activities. But there would not have been any conflict in their

meeting. It is important to bear in mind that boat-people and

land-people can co-exist because they live in different environments

and economic activities . On the other hand. hunting people

fought

hunting people over hunting territories. Farmers fought farmers over

farmland . Fisher-people fought fisher-people over fishing ground.

Reindeer people fought other reindeer people who attempted to take an

animal from their herd.

But people in different circumstances from one

another had no basis for quarreling. In North America, the native

hunter-fisher-gatherers of the wilderness were never directly in

conflict with the European settlers. Still, they came to an end

passively by the settlers cutting down the wilderness when they made

farmland. It is interesting to note that the major objecttions to

the arrival of settlers came from the Iroquian Natives, who were

themselves farmers. The Algonquian hunting peoples had less conflict

with settlers - until the settlers destroyed the wilderness.

Moving from the Black Sea towards

the

Vistula it was a very marshy landscape, not very attractive to farming.

But going north beside the Dneiper one found high ground. It was

over such high ground that , later in history, farmer-herders moved and

settled, in several

waves, the last wave being Slavs pushing out the Balts of an earlier

wave. Other

expansions followed the central European highlands towards the region

now Germany, as well as south into the Alps.

Thus peoples living in their separate economic

niches, co-existed. They did not need to dominate the other as would be

the case if the two had been similar, trying to claim the same economic

niche.

But in the long run, after many generations, the two

dissimilar

peoples could combine the best

of their two cultures and produce a new one that was superior to the

original two. (I have already discussed above the obvious merging on

boat peoples and reindeer peoples in arctic Scandinavia, giving rise to

the reindeer Saami.) But it would only develop if the combined culture

was better than the original ones in their pure form. The resulting

mixed culture, if it were more successful, would produce more offspring

and crowd out the older distinctive cultures. The ethnicity, the

language, of this mixed culture would depend on which tradition was the

most important in the way of life, forming the core of the mixed

culture. In the north Baltic area, for example, the successful result

was a combination of hunting-gathering-fishing plus a settlement with