3.

SOME EXAMPLES OF EXPANSION BY SEA BY NON-WHALING ABORIGINAL PEOPLES

Looking at Algonquians, Picts, and non-whaling Pacific Coast Tribes

by

ANDRES PÄÄBO

Synopsis: When the long-range seagoing peoples

expanded around the arctic sea, in their quest for whales, porpoises,

walrus, seals, and so on, they became established in whatever new

environment contained these sea animals. However all along there was

also fish as a mainstay of their lives, and so these people could enter

territories in which such large sea-mammals were rare, but fish was

plentiful. Since fish (freshwater fish) were also found inland,

skin-boat peoples could also travel up rivers and settle inland,

thriving on annual harvests of plentiful fish like salmon. This chapter

deals with a few identifiable descendant peoples, arising from the

original oceanic peoples. These people arose in a very simple way

- they descended the coasts from the arctic waters, and adapted to

lives that were less dependent on sea mammals and more dependent on

fish. The peoples discussed here include the "Picts",

Algonquians, and selected Native peoples of the Pacific coast of North

America.

Introduction

CONTINUING INVESTIGATION OF EVIDENCE OF

EXPANSIONS BY SEA

The theory of the expansion of Boat Peoples from

the watery lands south of the Ice Age glaciers ( PART ONE: THE ORIGINS AND

EXPANSIONS OF BOAT-ORIENTED WAYS OF LIFE : Basic Introduction to

the Theory ), proposes that there was an original expansion across

northern Europe of peoples originating in the "Maglemose" archeological

culture. PART TWO of these articles looks in more detail at the branch

of the boat people who took first to the Baltic sea with large dugouts

(archeological "Kunda" culture) and then headed north to the arctic

ocean, and developed skin boats because there weren't any large enough

trees for seagoing dugouts. (See PART TWO: SEA-GOING SKIN BOATS AND OCEANIC EXPANSION:

The

Voyages of Whale Hunters) In PART TWO we also looked at the

Inuit language and found

remarkable parallels with Finnic (Estonian and Finnish today), thus

producing an echo

of the circumpolar movements of whale hunters. Then we looked at the

Kwakwala

language of the Northwest Pacific coast of North America, a language of

the Wakashan languages of cultures with whaling traditions, which

showed amazing parallels both Inuit and Finnic languages.

Obviously if there are sea peoples

in the arctic, once they have the capability to do so, and are in

pursuit of large sea mammals like whales and seals, with success and

population growth, they will start to migrate around the arctic seas,

and even south along oceanic coasts in search of the fertile waters

filled with sea life.

We have already considered the migration

across the North Atlantic to establish the "Dorset" culture of the east

part of the North American arctic waters. In this article we will

consider the evidence of migrations southward along both the Atlantic

and Pacific coasts. (PART ONE has already looked at the Wakashan whale

hunters of the Pacific coast of North America, and made a mention of

the Ainu seagoing original peoples of Japan.)

THE

AREAS OF STUDY IN THIS ARTICLE

Once the skin boat peoples

were established in arctic Norway, they were free to migrate southward

along the Norwegian coast and into the British Isles, and even further

south, establishing people ancestral to the Picts. We are not speaking

of whaling peoples, but 'regular' sea-hunters and fishers. Similarly

once the

circumpolar whalers were in the arctic near Greenland, some were free

to migrate south along the Labrador coast (the same way the Icelandic

Norse ventured south in 1000AD) and establish themselves there, and

south to Newfoundland and even further. At the lower end of the

Labrador coast was the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River, which was the

gateway into a large inland water system known as the Great Lakes. They

would have travelled into that water system. There they would have

become ancestral to the Algonquian speaking peoples, the ones best

known for the birch bark skin boats (canoes).In most cases we will find

that these peoples were attracted to salmon, which were probably

migrating up and down rivers to both Atlantic and Pacific in large

number, Atlantic eels perhaps too,

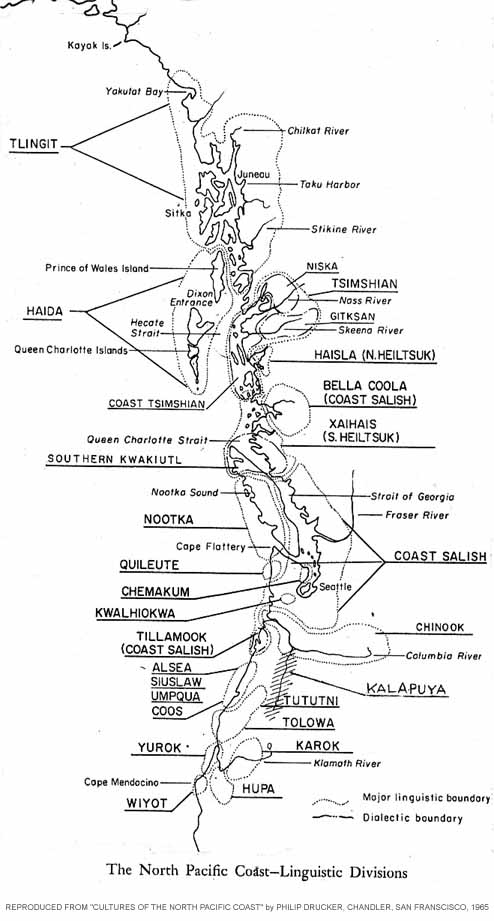

Similarly circumpolar sea peoples

arriving at the Bering Strait were free to descend south along the

Asian and North American coasts (although ocean currents there favoured

the Asian side) We will look at a few Native cultures that

were

found and recorded at the midpoint of the NorthAmerican coast for

cultural and linguistic features that would tie them to the boat-people

expansion. PART TWO already looked at the Wakashan (specifically

Kwakiutl) whaling peoples of

the Pacitic coast.

Because voyages across the North

Atlantic would begin in the Norwegian arctic waters, we begin our

journey with some attention on the great number of rock carvings found

at Alta, Norway. I believe that Alta, Norway, was a staging area

for

many of the migrations that contributed to the culture of the

northeast quadrant of North America.

The

First Wave of Seagoing Expansion

BALTIC >

LAKE ONEGA > WHITE SEA > ARCTIC NORWAY > ALTA, NORWAY

Archeology shows that large harpons alongside adzes

first appear in the "Kunda"

culture in the location of today's Estonia

southward along the east Baltic coast, and it makes sense that these

were the first boat people to make large dugouts and venture into the

sea to hunt large sea-mammals. With the success of this culture,

breakaway groups expanded to other places with sea-mammals. Lake Onega

and White Sea rock carvings suggest the dugout canoe was

replaced by

skin boats made of moosehide forced by the lack of lack of large enough

trees in the arctic to fashion large seagoing dugouts. Once the skin

boat concept was established, it was an easy step to make them larger

and larger, and there are rock carvings showing this larger boat,

maintaining the moosehead on the prow that honoured the animal from

whose skin the boat was made.

While the east Baltic, then Lake Onega and the White

Sea were the first

staging areas for the expansion of sea peoples into the northern seas,

the

coast at Alta, Norway, was the second staging ground. This article will

look at migrations that seem to have originated from developments

concurrent with the development of the congregating site at Alta Norway.

The region of

Alta, Norway, was originally under glaciers, so that location did not

become relevant until the glaciers had receded, freeing up the coast as

well as the interior. As we saw in PART TWO, the first boat peoples to

venture into the fertile waters off the coast of arctic Norway,

probably returned south for the winter. For one thing the moosehead on

the prow signified that these people must have regularly visited places

sufficiently south to find the animal known as the moose (or in Britain

known as the "elk", in Finnish "hirvi", in Estonian as "põder"). As I

pointed out in PART TWO, the rock carvings at Lake Onega show a man on

skis pursuing a moose. The moose images in general do not show any

antlers. Since antlers are grown in summer and lost in fall, it follows

the people who made the carving were not there in summer and never saw

the moose with antlers. Thirdly, winter was dark in the arctic and

people would have nothing to do but wait out the winter. The further

south they went in winter, the more light they would have to hunt moose

and other winter animals. Last but not least, rock carvings found on

islands in the Norwegian arctic show images of forest animals, and

nothing of the animals they are there to catch - as if expressing

homesickness for the other location.

Thus the first stage of the expansion into the

oceans represented those sea-hunters who went into the arctic seas in

spring, harvested sealife during the summer, and returned in fall,

arriving back in the upper forest zone when the moose bulls had lost

their antlers. As we saw in Part Two, some such peoples also

became whale hunters because the rock carving shows whale hunting

activity from large skin boat with the moosehead on the prow. It

is easy to track these peoples from the moosehead on the prow.

The second stage I believe begins when a tribe or

extended clan decides not to return south. Archeologically speaking

this would be the "Komsa" culture found on the arctic coast of Norway.

The people who occupied the site archeologists have found appeared to

have simply stored food and waited out the dark winter. By not

returning south, these people could no longer make their skin boats

from moose. As we see in photographs below, the Alta carvings show an

abundance of skin boats with reindeer heads (the snout is square rather

than round) - indicating that those who stayed simply used reindeer

skins sewn together. Since reindeer lived further north than the moose,

there was no need to descend into moose forests. Obviously those

seafarers that actually left arctic Norway could no longer use reindeer

hide, and probably used walrus hide, as that is what was used by the

Inuit of arctic North America - although it is possible Greenland

"Eskimos" whalers may have managed to employ whale hide.

Originally that was entirely the origin of

peoples harvesting the Norwegian arctic waters, because glaciers

blocked access to the Norwegian arctic from below. But when the

glaciers had shrunk, access to the coast from the interior was easy,

even easier than today considering the interior lands were more

depressed and wet. As a result, a new pattern of migration

developed, in this case between the coast in the Alta region, and the

interior regions. Indeed the boat journey via the rivers was easy, and

the ancient elevated Gulf of Bothnia and the lakelands of what is now

Finland were not far away for boat peoples. For this reason it may be

possible to make links between the rock paintings on rock faces in

Finland and the rock carvings at Alta. The Alta images are carved

in granite and thus have preserved themselves well. The Finnish rock

paintings are worn and often hard to make out, since paint is not as

durable as a carving in granity; but it is reasonable to assume that

they are basically from the same peoples. There are large areas in

between without any evidence of images for one simple reason - it is

marshland and a lack of granite walls or floors.

Alta

Norway, a Major Location that Was a Multi-tribe Meeting Place and

Launching Place for Sea Voyages

THE

TRADITION OF MEETING PLACES

Alta, Norway is a location that must have been

the

meeting place for many tribes - tribes who were indigenous and

harvested the seas, tribes who arrived seasonally from the interior,

and possibly visitors from farther away.

The visitors, finding granite

hills engraved with carvings, would have added their own at every

visit. Such places where many tribes congregate, to trade, exchange

news, socialize, and engage in common festivals are well known

throughout the world of northern hunting peoples. The Lake

Onega region was one such place where many tribes congregated. The

region at the mouth of the Vistula

another. It is possible to predict such locations according to

the

organization of water systems. Such locations appear in archeological

investigations as different archeological "cultures" overlapping in

that area, suggesting they came together, camped near one another. It

is in such locations that sites of religious/spiritual nature can be

found.

THE ALTA,

NORWAY ROCK CARVING SITE

The Alta area has granite ridges, and because granite is

hard, it has

been determined that the carvings are between 6200-2000 years old. This

means it was begun by the earliest skin boat peoples who visited the

fertile waters off the coast - waters warmed by the North Altantic

Drift that reached that location. We can also interpret the age

as evidence that the skin boats were in use first in arctic Norway

before it arrived anywhere else.

But the Alta site continued to recieve tribes both

from along the coast and from the interior, as suggested by the fact

that carvings are as new as 2000 years ago with some examples as late

as 500 years ago. One can argue that a site that starts a tradtion of

rock carvings both attracts more carvings, and in general grows in

importance as a congregating site. The following information box

shows some images from the site (images stolen from the internet)

The congregating site was

very important to nomadic hunting peoples because they moved around the

environment as clans for most of the year, and needed to meet each

other to share news, find mates, and carry out celedbrations.

It is obvious from

common sense that eventually some

arctic seagoing people would no longer travel south in the winter, this

is clear too from the fact that the Alta carvings show a large number

of skin boats with reindeer, not moose, heads.

But throughout its history the Alta site would have

attracted peoples from the interior, from the Scandinavian interior,

rather than for the Lake Onega area which was considerably further

away. As the map shows Alta was located north of the mountain range and

could be reached from rivers descendng into the interior. These

interior people would have had small skin boats for navigating rivers,

and as I will argue below, are one of the ancestors of the Algonquian

peoples of the northeast quadrant of North America - the hunting people

of the birch-bark canoe. But most of the carvings, from more recent

times generally reflect the historic "Finn" culture in general, which

originally

was found in seagoing and forest peoples, and not just the reindeer

tenders that have survived into modern times. (The original word "Finn"

became "Lapps" and as later as the early 20th century, there were

"Forest Lapps" and "Fisher Lapps" as well as the "Reindeer Lapps" who

wanted their own name "Saami" which reflects the fact that they are

also Finnic-speaking remnants of the reindeer peoples, which are also

found towards the east as the "Samoyeds".

It is important to make the connection between the

aboriginal peoples who came to Alta, and all the vanished peoples that

the Germanic conquerors of the Scandinavian Peninsula referred to

as "Finns"

since they took over. It is easy to see why the regions to the interior

was called "Finnmark". Towards the east there was "Finnlanda". It

underscores the fact that the "Finns", were the aboriginal

peoples, But there has been debate as to how they relate to the

Finnish who cover the same landscape as "Finns" of today's Finland. An

obvious answer it that they are almost the same, since when Finland

became a country there was not sharp distinction between the natives in

the wilderness and the "Finns" in the more developed southern Finlands.,

The map below in any event shows how interior

boat peoples living in locations with moose, could have made the

journey. There were also routes through the mountains that were used

for trade in the nearer era.

North American Algonquians - the

Rock

Art Evidence

ROCK PAINTINGS ON BOTH SIDES OF THE ATLANTIC

Anyone who is aware of the rock paintings on the

walls of cliffs in Finland, which were painted from boats, and also

those in North America around the Great Lakes, cannot help but notice

their similarlities. In both regions, separated by the Atlantic, people

in canoes found it necessary to stop beside sheer walls descending to

the water, and make paintings using red ochre. Did these people first

come from Finnic sources in northern Scandinavia, via the Alta

gateway, first crossing the North Atlantic in skin boats, and then

travelling inland in shallower vessels?

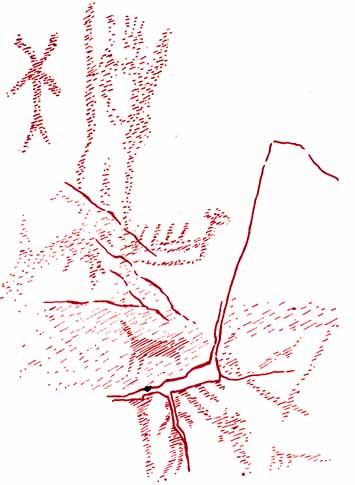

This

image, by Dewdney reproduced from Indian Rock Paintings of the Great

Lakes (S. Dewdney & K.E. Kidd) represents a section of the

rock paintings found on the rock face beside the water at Bon Echo

Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada. In the center we see a boat with a

prow with an animal head. Does this depict a skin boat of Scandinavian

origin?

LATER ARRIVALS TO

NORTH AMERICA HAVE TO 'MOVE ON'

A very important concept regarding aboriginal

peoples, was that, like all humans, they were very territorial.

Supposing the arctic waters west of Greenland were already inhabited by

seagoing peoples, an early "Dorset" culture, already established early.

Then later, when

the Alta area became a new staging location for boats heading west into

the ocean, new migrations would have run into the "Dorset", and been

forced southward along the Labrador coast. It is there that ancestors

of the Algonquians of the northeast quadrant of North America became

established. Thus, in a sentence, the Algonquians could have

originated in a second wave of migrations, from the second staging

area, Alta. We have nothing to prove it, other than the concidences of

making rock paintings on How similar are the

Canadian

rock paintings to those in Finland, when

comparing the two locations?

The rock paintings at Lake

Mackinaw, Ontario, are interesting because they are towards the east,

hence closer to the direction from which visitors would have come.

The image above shows an impressive location that

canoes would have

passed on a route northward from eastern Lake Ontario. One should not

imagine that men made intentional journeys to such cliffs, but rather

that it was on their normal long-distance canoe routes, and that the

voyagers were impressed by the vertical rock walls and were moved to

make drawings. (Possibly feeling

the same way as a tourist with a camera). Obviously where there were no

cliffs descending to the water, there were no drawings. We should not

assume that because a region has no drawings the people did not pass

through there. There simply

were no places to put drawings. Southern

Ontario does not have very many locations such as the one at Lake

Mackinaw in southeast Ontario. The greatest concentration of rock

paintings done on cliffs beside the water are found alongside Lake

Superior and lakes towards its northwest. A detailed study of the Great

Lakes rock paintings is found in Indian Rock Paintings of the Great

Lakes (S. Dewdney & K.E. Kidd)

North American Algonquians - the

Linguistic Evidence

"CANOE"

A WORD FROM NORWAY?

There has been a debate for some time as to the

origins and meaning of the word "Canoe". Native linguists have

offered some proposals, however there is a third alternative related

to Scandinavian arctic origins. So far we have talked about

skin boats depicted at Alta, clearly designed for use in the ocean. So

far we have assumed that the boats used on rivers were dugouts. The

fact that the Inuit possessed a small skin boat known as the kayak,

shows that where trees were completely absent, the small arctic dugout

was replaced by a small arctic skin boat. But did skin

boats replace dugouts in southern regions too? The birchbark canoe, is

certainly an example of skin boat construction. It is basically a skin

boat, except the skin used

is birch bark sewn together. Their advantage was their light

weight. They could be easily carried from one water system to another.

Is there any evidence of

skin boats in ancient Finnic Scandinavia, used in the interior in the

manner of the birch bark canoes of the Algonquians - making them light

to be readily carried from one water body to another?

Historical records do speak of small

skin boats used in northern Scandinavia among peoples known by names

such as the Anglo-Saxon Cwens,

Germanic Quans.

Historical records

speak of the Cwens crossing the northern part of the Scandinavian

Peninsula easily because of small skin boats that they could portage

with ease. To be specific, they are described crossing over into the

Lofotens to attack unwelcome Norse settling there as the Danes

conquered Norway in 800-1000 AD.

The earliest and most extensive

description of it comes from a northern Norwegian of the 9th century,

"Ohthere" (in Anglo-Saxon), who spoke about them at the court of King

Alfred of Wessex, where his accounts were recorded. King Alfred

presented his accounts in his Orosius. The man

Ohthere, said as follows:

Then along this land southward, on the other side (east) of the

mountain, is Sweden, to that land northwards; and along that land

northwards Cwenaland. The Cwenas sometimes make attacks on the Norse

over the mountain, and sometimes the Norse on them; there are very

large freshwater seas between the mountains, and the Cwenas carry their

boats over land into these lakes and thence make attacks on the Norse;

the boats are very small and very light. [from Orosius]

I believe that the Cwens, identified today as

the Kainu dialect at the

north end of the Gulf of Bothnia, may have

been a tribe from among the original Finnic natives of forested Sweden.

Elsewhere in the historical record, they appear with their names

expressed a little differently, such as Quans. Because of the

similarity of the word to the Swedish word for 'women' (kvinna) a myth

developed in history that the Quans

were people dominated by

women. But the truth may be that when the region now Sweden was invaded

by Germanic men, that they took wives from among the natives, from

among the Quans/Cwens and

that the Swedish word 'kvinna'

came from them. (It would be similar to in North America the word squaw

entered the English language.)

I spoke earlier of how the original name of the boat

peoples was something like UINI or with lower vowels UENE and meant 'of

the water-floating', but the word could also refer to the boat itself -

the instrument that floated on water. Thus, the actual name of the Cwens/Quans may have

actually been NAHK-UENE, 'skin boat', (employing the Esto/Finn

nahk 'skin,fur'). Observers

would have interpreted this longer word as

K'WEN. It is interesting to note that the Finns called the descendants

Kainu, which means the

original may have been NAHK-UINI since the form

with the 'I' can more easily transform to Kainu (NAHK-UINI -->

K-UINI --> K-AINU). Note that it is also

possible to take the approach that the initial

"K" sound was a dialectic feature at the start to launch the UINI, and

not an abbreviation of "NAHK". After all, in the same region, there was

also the word "Finni". With "Finni" versus "Cwens, etc", we may be

talking about Germanic speakers hearing two native dialects, one which

they interpreted as having "F" at the front and the other as having "K"

at the front. Note this is just an observation. Finnish scholars are welcome to look into it more closely.

The K-UINU appear to have carried on

trade up the Tornio River reaching the Lofotens via Narvik, thus

placing peoples with a more developed, trader, character, in the

Lofotens area before the arrival there of the Norse during the

800-1000AD conquests by the Danish kingdom of the time.

The K-UINU skin boats were not kayaks, but at

least, they presented examples of light skin boats used for navigating

through river systems. It is not known if such boats were always made

out of animal skins or whether at any time bark, such as birch bark,

was used. Certainly there was birch bark through the area.

The northern Algonquian people of Canada are

now famous for the use of boats that used birch bark as their skins.

Perhaps, just as the invention of the kayak is the reason for the

expansion of the Inuit, the invention of the birch-bark canoe, from

original models that used animal skins, was the reason for the

expansion of the Algonquians. Birch bark was readily everywhere in the

northern forests. There was no need to procure numerous skins from

large animals. Skins were better used for clothing.

The argument in favour of this

approach to the origins of the word 'canoe', is that ancient peoples

named things by describing them. Alternative explanations fail to

provide a descriptive meaning as clear as 'skin boat' The

name for the

vessel would have endured, even as the original meaning was

forgotten. This leads us to investigating whether the Algonquians

of Canada also adopted some words brought by visitors or immigrants who

crossed the North Atlantic in skin boats.

DID VISITORS FIND RESIDENCE OR SIMPLY INTRODUCED INNOVATIONS?

There are two ways a word from another

language can appear in a language. On the one hand there is the genetic

method, where the word is inherited and suggests the language is

actually related to the other language. The other, more common way is

that there was once contact with the other language and the word was

borrowed. In looking at Algonquian languages we are not trying to show

that they are genetically descended from the same distant parents as

the Finnic languages. In order for that to be true we should be

finding significant number of similar words, but more importantly

similarity in grammar. For example, the Inuit language has noticable

similarities to Finnic grammar, suggesting there might be a genetic

explanation.

We already looked at words in some languages. In PART TWO - SEA-GOING SKIN

BOATS AND OCEANIC EXPANSION: The Voyages of Whale Hunters.

-

we

looked at many words in the Inuit language of the North American

arctic, that showed close parallels with Estonian and Finnish. If here

we propose the Algonquian canoe-oriented hunters of the northeast

quadrant of North America, also came largely across the North Atlantic,

then we should also be able to find connections across the North

Atlantic between Algonquian languages and Finnic languages. Our results

will be significant whether the words are genetic in origin or simply

borrowed. Both will suggest there was contact sometime in the last

6,000 years, while the first will suggest the immigrants were very

successful and became enduring residents of the northeast quadrant of

North America. What we will find, most probably, will be evidence of

contact.

For the visitors to become residents,

there cannot have been people there already with boats and defending

their territories. But if there were no boats, the immigrants would

have found an empty territorial niche with no indigneous people

defending it. We must never forget when we speak of migrations that

either there has to be an empty niche to enter, or the immigrants have

to wage war and drive out the indigenous occupants of the desired

territory.

Perhaps northeast

North America originally did not have people with a boat-using way of

life (ie earlier people may only have used boats, rafts, to cross

bodies of water, not to use as an everyday vehicle for

hunting-gathering.) They could have become established easily. More

likely, perhaps peoples who crossed the North

Atlantic, bringing the boat culture, mixed with indigenous

hunters, and the combined culture, adding boat use to hunting,

experienced a dramatic explosion that caused the migrations

inland. This would be the most common manner by which new cultural

innovations appear - being adopted, copied. It is how most farming

practices spread in prehistoric Europe after it had become visible.

The fact that Algonquian languages were found up all the

water systems draining into the northern Atlantic, proves that there

was an introduction of new culture that was so beneficial that it

caused a population growth that promoted expansion. Only a small

number needs to have come, who then intermarried with the natives and

produced a more successful culture causing their small beginnings to

expand dramatically, absorbing or diminishing the original native

hunters.

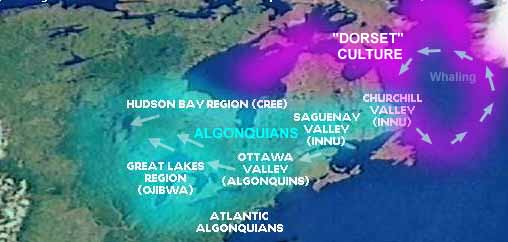

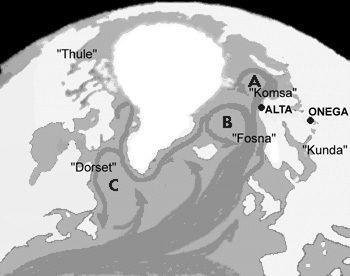

This map shows how

easy it is for oceanic boat people (labelled "Dorset Culture) to access

the northeast quadrant of North America. both from the north via Hudson

Bay, and up the St Lawrence River to the Great Lakes.

North American Algonquians -

Their Arrival and Origins?

What is interesting about the Algonquian languages

is that their

distribution in northeastern North America is such as one would expect

if boat peoples travelled up all the rivers after descending via the

winds and currents of the Labrador and Newfoundland coast, and finally

being discouraged to go further south only below Newfoundland where the

Gulf Stream current came from the opposite direction. The exception to

this pattern are the Cree, who lived in the water basin of the south

part of Hudson Bay. It is however possible that the Cree transferred

into this northern water basin after first travelling up rivers such as

the Ottawa or Saguenay, and then followed the Hudson Bay southern coast.

If the Algonquian boat-using

hunter-fisher-gatherers originated from voyagers who crossed the North

Atlantic at an early time then we have to consider that the voyagers may

have all been men, and they took wives from people already found at their destination,

indigenous people without a boat-culture. The combined talents perhaps

produced a new more prosperous culture that caused a population

explosion that then fuelled the expansion up the rivers. We must not

forget that we cannot have a dramatic expansion of peoples without

population growth, and we cannot have population growth without some

beneficial development. I suggest that if the original peoples of

northeast North America did not originally use boats as a daily

vehicle, then a

people who came with a boat-culture already developed, would have

introduced the conditions that would have caused the required

population growth as they would have entered an untouched economic

niche. For example, what if these newcomers discovered and exploited

the bountiful supply of fish in the "Grand Banks" off the south coast

of Newfoundland?

We also note that the Algonquians who retained

the name Innu to describe

themselves, were within Quebec and Labrador.

Is it possible then, that the influence of the newcomers was strongest

where they first came, and that the influence degenerated with those

who migrated westward into the interior?

Are the Algonquians descended from the arctic

"Dorset" culture that preceded the "Thule" culture identified with

today's Inuit? Common sense is that the "Dorset"

did not vanish. The scholarly belief that the Inuit ("Thule") arrival

from the west arctic wiped out the "Dorset" does not seem believable.

If there had been battles in which the Inuit ("Thule") were more

powerful, there would have been refugee migrations of "Dorset" to other

locations and an obvious direction was southward. Is it a

coincidence that the Newfoundland Boethuks, scholars say, arrived in

the Newfoundland area around the early centuries AD, about the time the

"Dorset" culture is estimated vanished. The Boethuks, moreover, had

skin boats. In one of the Norse Vinland Saga's the Norse are met

by a fleet of people in skin boats.

As stated at the start, the INI form was used

by the Algonquians of Labrador and Quebec in the form Innu. Nonetheless

the more westerly Algonquians still had words of the form inini to mean

'man, person'. Since the Inuit

had inuk

to mean 'man,

person' we have

to conclude that there is some sort of connection between them, that

they both ultimately originated from peoples who came with skin boats.

Being from Estonian descent, I have always found it remarkable that the

Estonian word for 'person' is inimene, where -mene is an ending

TRACING SKIN BOATS BACK TO THEIR ORIGINS

We began above by speaking about Alta, Norway, and

also about the coincidence of similar rock carvings and paintings being

found in North America. Is this evidence of the transmission of a

culture across the North Atlantic, that may have passed through a

"Dorset" stage?

The seagoing peoples at the Norwegian coast would

not have only travelled west but also south. They could have followed

whale migrations south to Portugal. They could have given rise to the

"megalithic" culture, that left megalithic constructions up the west

Europe coast, and then up the Irish Sea and into the northern Isles,.

There

is no question that there once existed an "Atlantian" people.

They travelled the north Atlantic ocean, camping on islands, as we can

see in the illustration of Greenland Inuit whale hunting. They were

short people, and that is to be expected too, as an adaptation. People

who travel extensively by boat need strong upper bodies, but can have

short legs (Short legs on large torsos can be still seen among the

Inuit - short legs are also good for reducing loss of body heat)

Author Farley Mowat (Farfarers, 1998), pictured a people he called

"Albans" based in the British northern islands. He pictured them being

most interested in walrus, and travelling as far as the Labrador coast

to obtain walrus ivory to sell in Europe. In his book Farfarers,

Mowat's view of the skin boat

traditions of the northeast Atlantic was far too narrow, however. He

made no mention of the rock paintings of skin boats in Norway, and made

no connection between the Norwegian examples of skin boats and the skin

boats of the British Isles, recorded in historical records and

surviving through the centuries as the Irish "curragh".

We can read with interest however

when

Farley Mowat reveals that in the traditions of the Shetland Islands in

the north of the British Isles, sea-harvesting peoples called the

"Finns" appeared.

Existing Shetland traditions speak of

a people called Finns who

inhabited Fetlar and northwest Unst for some time after the Norse

occupied Shetland. This name is identical with the one by which the

Norse knew the aboriginals of northern Scandinavia. It is also the name

given by Shetlanders (of Norse lineage) to a scattering of Inuit (sic).

who, in kayaks, materialized amongst the Northern Isles during the

eighteenth century.. (Mowat, Farfarers: Before the

Norse, p 110,

Toronto, 1998)

But it did not occur to Mowat that these were

the same people as the ones he was looking for, and not some other

people? He was looking for people closer to himself - settled people

living on the coasts - and thus did not seriously consider "Finns" to

have been identifiable with "Sea-Lapps" from the Norwegian coast, and

that possibly they were less primitive than the Inuit/Eskimo he assumed

they were.

The difference between the Altantic seaharvesters that

were called "Finns", and those who left a record of skin boat use in

the British Northern Isles, may be simply that the latter became more

localized by becoming more involved with the economies of the interior

of Britain. There is indeed proof that skin boat peoples of the British

Isles were more localized than their migratory ancestors, and

found everywhere on the coasts, at least on the west side. According to

Mowat in Farfarers, the Roman poet Avienus, quoting fragments from a

Carthaginian periplus (seaman's sailing directions) dating to the six

century B.C. described a rendevous with native British in skin boats as

follows.

To the Oestrimnides [Scilly Islands]

come many enterprising people who

occupy themselves with commerce and who navigate the monster-filled [ie

walruses, seals, whales, propoises, etc] ocean far and wide in small

ships. They do not understand how to build wooden ships in the usual

way. Believe it or not, they make their boats by sewing hides together

and carry out deep-sea voyages in them. (quotes in Mowat,

Farfarers)

The people described in the above

passage are clearly not the long ranging oceanic aboriginals, but still

they are probably descended from them. Finding good conditions in the

British Isles, and the ability to trade wares from the sea for other

goods, they would have formed an intermediate culture. It is these

people that are identifiable with the archeological "Picts". They

exploited land resources and trade, (such as keeping sheep and goats on

various islands roaming wild, to harvest from time to time when

they stopped there).

Evidence that the skin boat of the

British Isles was descended from the Norwegian skin boats is found as

late as the 18th century. A drawing of a curragh from the 18th century

is interesting in that there is an oxhead on the prow. This is

remarkable as it suggests descent from an arctic European tradition of

putting the head of the animal whose skin is used, at the prow, a

practice that began with the moose-skin boats and the moosehead on its

prow, visible in ancient rock carvings such as those in the Norwegian

arctic at Alta, and Sørøya, and other places like Lake Onega.

It is only because of my noting the

animal heads on the prows of skin boats in Alta and Lake Onega carvings

that I saw the oxhead on the prow of this Irish curragh made of ox

skins.

When boat skins were later made of planks, the

practice of the head on

the prow seems to have continued for a time, giving rise to the "dragon

boat" concept. The presence of the "dragon-head" in Norse vessels

demonstrates that the Germanic conquerors of the Norwegian coast

(800-1000AD) became identifiable with seafarers purely from the Finnic

natives starting to speak the Germanic language (Norse), and

participating in the new Norse culture. The idea of Vikings originating

from Germanic heritage is false. Vikings originated from the Finnic

boat

peoples, and became speakers of Germanic Norse in much the same way

that North American Native peoples have become English speakers..

Another important historical reference

presents us with another truth that ought to be obvious - that the skin

boats of the British Isles crossed the waters to Norway as well. This

comes from Pliny the Elder dated to 77 A.D. in which he writes about

information from an earlier historian Timaeus whose original work has

been lost.

The historian Timaeus says that there

is an island named Mictis lying

inward six day's sail from Britain where tin is found and to which the

Britons cross in boats of osier covered with stiched hides. (Pliny,

NaturalHistories,

IV, 14, 104.)

Mowat suggests that this place called

Mictis might have been

Iceland. However if the skin-boat seafarers of

the British Isles had an intimate relationship with any location it may

have been the Lofoten Islands of Norway. We also note that since the

Gulf Stream flowed past the British Isles and north towards the

Lofotens, then the sailing was with the current.

If they travelled to the

Lofotens, that brings into play the Cwens

spoken about by Ohthere

(as discussed earlier), who seem to have carried on trade between the

Lofotens and the Baltic, employing portable skin boats, canoes.

Thus we can accept that many of these

oceanic skin-boat peoples, who ventured away from the Norwegian arctic

waters where they began, and then became localized among the British

Isles, tended to sheep on land behind their huts, and traded with

interior peoples; but at the same time the traditional way of life

would have continued as well: there were also the long-range migrations

of traditional oceanic people, who made circuitous migrations

from one sea harvest area to another. They would be the ones who would

camp

for a time on outer islands (like the Shetlands) to use as a home base

for harvesting the surrounding seas. The "Finns" of Shetland traditions

were not, I'm certain, accidental visitors of Inuit. I think they were

people who deliberately migrated in a circuit which touched on Iceland,

Faroes, Shetlands, and Norway.

Ocean currents, archeological cultures, and the Onega and Alta rock

carving sites.

Looking at the map above, showing how the ocean

currents

circulate in the north Atlantic, it is likely that the "Finns"

who touched on the

northern islands of the British Isles, can probably be identified with

the "Fosna" archeological culture of Norway, or at least, that part of

them who would have migrated in current circuit "B" (see map). These

oceanic people would have had no

interest in making their way into the dangerous surf close to the

coasts. They appear to have preferred camping in the outer islands

close to their fishing/hunting sites. Such

people would have travelled, through a year (or possibly several

years), between

the Lofotens of Norway, Iceland, and then back via Faroes and Shetland,

and then back to the Lofotens. They would time it to meet up with other

clans at a common congregating site.

As mentioned earlier, these people of circuit "B"

would also have stopped in the British outer islands (such as the

Shetlands, mentioned by Mowat). But a breakaway tribe must have

remained in the British Isles to become the peoples seen by visitors

over a millenia ago travelling in skin boats (which Romans called curucae and Celts called curraghs) in the remote coasts of

British Isles, mainly in the north and northwest.

According to historical references after the arrival of

Christianity Irish monks sought to get away from civilization to live a

solitary meditative life. They headed north into the outer islands, and

there they encountered short people who created dwellings that

resembled igloos made of

stone, that is, domes (or near domes with a small roof) created by

piling rocks round and round, sealed on the outside with sod so that

they were like underground houses. (Note that arctic Norwegian

dwellings were similarly semi-buried and often using sod to seal the

roof.) These short "Peti" (As a Norwegian text called them) that the monks encountered, appeared

also to have left goats and/or sheep to run wild on grassy

islands, so that when they returned to these islands they would be able

to harvest them for meat to supplement their seafood diet. Obviously

those "Picts" who became more settled, if any did,

became more diligent breeders of these sheep and goats. Such islands

would have been ideal for monks - there they would have solitude but also have familiar goats

and sheep to survive on. We are speaking of early Christianity in Ireland, shortly after the collapse of the Roman Empire.

Looking further in circuit "B", we can expect that

the seagoing peoples of circuit "B" also visited the outer islands

towards the east side of Iceland. This is confirmed by history

and archeology - which affirms there were aboriginal peoples,

Eskimo-like people who were inclined to

camp on the outer island close to the areas they fished and hunted.

Since these were seasonally migratory people, foreign observers would

never observe them to be settled anywhere. They would never need to

build any permanent dwellings anywhere.

Thus the absence of any early

permanent settlement on Iceland should not be construed as Iceland

being unknown. It was known, alright - by aboriginal peoples. They were

known by the "Picts" and "Finns" too insomuch as they themselves were

aboriginal or semi-aboriginal. Therein lies the problem in

Mowat's Farfarers

- he cannot accept that the people he envisions - the

"Albans" (one group among the Pictish north of the British Isles)

- were more primitive, more like Greenland Eskimo, than he wants

to admit. Scholars have tended to want to relegate aboriginal

peoples to the background, like wild animals and require that peoples

who did anything interesting must have been "civilized".

The exception has been archeologists

and anthropologists. They do not discriminate between civilized and

uncivilized. For them it is perfectly acceptable to envision aboriginal

seafarers who may have migrated

throughout the arctic waters, and known all about Iceland, the North

Atlantic, Labrador, etc. - already maybe 5000-6000 years ago. But there

remains a racist perspective which implies "aboriginals do not count",

and so there are endless debates as to whether the Norse landings

around 1000AD were the "first" or whether there were earlier

landings on Labrador or Newfoundland coasts, by Irish monks; or some

other group. Who cares? Aboriginals always knew, and European seagoing

aboriginals from the Alta area, visited and perhaps stayed millenia

ago. Archeology has found evidence of contact with Europe - primitive

aboriginal Europe -dating long before the "Norse" visits to "Vinland".

Oh yes, there were the

aboriginals camping on islands doing their sea harvest, but if we want

to find the somewhat civilized peoples like Mowat's "Albans" at Iceland

before the Norse, then we have to find farms. And

so Mowat ventured the theory that many of the farms attributed to

Norse, were actually stolen by the Norse after they wiped out the

"Albans". My criticism of "Farfarers"

is in another article. What he describes appears to be remains of

"Dorset" seagoing behaviour, and they may have been the source of

Algonquian peoples about 2000 years ago, or if not, earlier

The aborignal peoples named "Picts", as I suggested

earlier, may have actually had a name that meant 'hunters'. This idea

is inspired by the fact that the ancient Roman historian Tacitus,

mentioned one tribe in the Vistula River was called Peucini; This is obviously analogous to Estonian püügi(n) 'of the catching (hunting, fishing)'. Peti, Pehti, Picti,

etc fit that pattern too. What could be more descriptive than calling

the primitive sea-hunters exactly that - '(sea)hunters'. The later

historic Picts were different peoples, more settled and more civilized.

We are not speaking of those.

Is it possible that when the Romans conquered the British Isles and

circles them in their ships to assert their power, that the unrest that

followed caused the sea-hunting peoples to avoid returning to the

British Isles. They left, and moved their activity to Iceland and even

Newfoundland. The word Beothuk does vaguely resemble the Picti word,

which in an Estonian-like form would be püükide (people) of the catches' or püide. Given

that the Anglo-Saxon monk Bede wrote that the "Picts" in the British

north in his time (6th century), had "come from Scythia in longboats",

the historic "picts" could have been long distance traders from

Scythia. But "Scythia" had been defined by the Romans as being the

region that began at the east Baltic coast. That coast was where the

Estonians were located. So it is possible that Estonian-originating

traders had colonies who were active in fetching sea-goods from the

actual Picts. This would therefore mean that the word püükide was indeed the source of the word Picti.

THE

JOURNEY OF PYTHEAS 320BC

Another piece of history that involved

the North Atlantic is the journey of Pytheas to Iceland, which he

called Thule. It is assumed by most academics today

that Iceland was the Thule

mentioned by the Greek traveller Pytheas,

who voyaged in the north around 320BC, presumably with natives as hosts

or guides. More likely he accompanied traders. We should not assume that Pytheas sailed unknown

waters of the north with a ship and crew from the Mediterranean. He was

obviously taken by people who knew the region and Thule was the name

they gave to Iceland.

Most likely Pytheas was a Massilian merchant

(ie at Marseilles) who was always engaged in commercial dealings with

Veneti merchants who were established in Brittany and constantly

sailing to and from Britain (according to Julius Caesar), as well as

delivering goods south via the Loire and Rhone River routes. He may

have asked the Veneti traders if he could accompany them north, and if

they would show him where major northern goods came from - tin, walrus

ivory and skins, and amber - since in fact his journey proceeds first

to Britain (where tin came from) then to the Orcades (Orkney Islands)

where once there were walrus herds, and finally it appears all the way

to the southeast Baltic, where the island of Abalus was identified as

the source of amber.

We have mentioned often that the

original Scandinavia and northern Britain was probably originally

"Finnic", and that means linguistically as well. Indeed even today the

surviving northern reindeer Saami are considered linguistically Finnic.

The next closest are the Finns and then Estonians. (I don't know the

Saami language, and therefore my comparisons are with Estonian ) Thus

it is interesting to note that the word Thule seems to be a simple

Finnic word that easily describes Iceland. Considering that Iceland is

an island with active volcanoes that erupt ever generation or so, it

would be natural to call it '(island, land) of fire'. In Estonian it

would be pronounced exactly as the Greeks would say Thule

(In Greek Th

represents the softer "D" sound. In Estonian and Finnish the single T

is spoken like a "D". A double T is needed for the harder T of

English). While the academic world is non-committal in identifying the

language that existed in Norway and Sweden before it was conquered by

the Germanic Danes, "Finnic" has always been the clear option since at

least the Saami survives today, and their language has been found part

of the Finno-Ugric Uralic languages. There is no better alternative,

and the notion that the original language has completely vanished is

not believable. If we find words with strong coincidences to Finnic in

languages of North America then we are speaking of connections to the

Scandinavian and Baltic area that predate any alternative theories of

Finnic language origins.

The modern Estonian word for 'volcano'

is tulemägi literally

'fire-mountain', and so the word tule

is correct

in association with volcanoes. "TULE-" is the stem to which endings are

added, and so a foreigner would always hear the stem as case endings

are added (tule-sse, tule-st,

tule-lt, etc). Thus Pytheas, listening to

his hosts speak, would repeatedly hear "dew-leh" which would be written

in Greek Thule. Finnish adds

an -N for the genitive, hence 'of fire' is

tulen, which agrees with one

ancient reference which called it Tylen.

Because they have long disappeared,

assimilated into the Norwegians, most people are unaware that the

peoples formerly called "Lapps", earlier called "Finns" and today

called "Saami" were not a single cultural group. Generally the literature says, there were three types of "Lapps", the

Sea-Lapps, Forest Lapps, and Reindeer Lapps, with only the last

enduring

in the Norwegian north into modern times. The Reindeer Lapps have

endured strongly, and that is why they, or "Saami" as associated with

reindeer herders, today, and the public knows little of the fact that

the whole Scandinavian peninsula was once filled with "Finns" of every

nature. In other words, at one time, perhaps as late as the stories of

"Finns" camping on the Shetlands, there were "Sea-Lapps" or "Sea-Finns"

down the. Norwegian coast, and travelling into the British north to

fish; and there were "Forest-Lapps" or "Forest-Finns" across the entire

Scandinavia where land was not under the Germanic plow, as far as

Finland and beyond. Meanwhile southern clans and tribes, those in

greater

contact with encroaching farmers, whether Celtic or Germanic, adapted

towards more civilized ways - adopting farming, engaging in trade,

following European culture.

THE

DISAPPEARANCE OF THE 'PICTS' or

'SEA-FINNS"

History reveals that Britain was

invaded by Romans and Celts, and then by Germanic invaders. After the

collapse of the Roman Empire, and the withdrawal of Romans from

Britain, history states that there were three groups fighting to seize

power in the void left by the departure of the Romans - the Germans

(Angles, Saxons, etc) pushing in from the southeast coast, the Celts

pushing in from the southwest coast, and the "Picts" from the

north. When the term "Picts" is used in historic texts, it refers

generally to all the peoples in the north, which would generally tend

to exclude the primitive peoples hidden in remote places. What is

important is that

the north was different from the Romans and the Celts, and had its own

language, which was presumably the native British language.

History reveals that when southern civilization

pushes into the north, it assimilates natives from south to north; thus

it is a reasonable assumption that the northerners, whether

seafarers or not, were descendants of the original British who retained

their original language and culture. (Those in the south had become

Romanized or Celticized) Past historians have wondered about the

origins of the "Picts" of northern Britain.

After Britain had been taken over by

Anglo-Saxons, Ireland by Celts, and the Scots were beginning to take

over in the north, a monk scholar named Venerable Bede, in his

description of Britain, attempted to identify the "Picts" of his time

and their origins. Obviously deriving his information from arrogant

patronizing Celtic sources, perhaps Irish monks, he told a strange

story of Picts arriving by sea in longboats, attempting to land in

northern Ireland, and being told by the Scots there that the land was

full and they should cross over to what is now Scotland. The Picts in

Bede's north were a peculiar people in that they followed their descent

matrilineally. It is in the nature of the Irish legends to try to

explain

prevailing realities; thus the explanation for their matrilineal

culture was that when the Scots told them to move on, the Scots also

gave the Picts Scottish wives because the Picts came without any women.

Out of gratitide the Picts therefore kept track of the lineage of these

Scottish woman.

This story is obviously self-serving

self-glorification on the part of Scottish and Irish legend-weavers. If

we investigate the matter, the evidence seems to point to a different

story. The Picts, descended from native people, were in northern

Ireland first, and the Scots were migrating from the southern parts of

Ireland in search of a place to settle. Reaching the north, they found

the Picts there, and it would be the Picts that told the Scots to cross

over into the northern part of Britain, since the first Scottish

settlements appear on that side. The Picts who told the Scots to move

on, according to Ptolemy's geography of HIbernia (Ireland in the Roman

Age), were probably those he called Rhobogdi.

This word can be

interpreted as a low vowel dialect version, or an interpreter's

corruption, of a word that in higher vowels would sound like RHIBIGDI.

If we assume that RHI- is some sort of descriptive prefix, then we have

BIGDI, a word that is a perfect candidate for the origins of the word

Picti that first appeared in

Roman records in the third century AD.

(Yes, the word is first used with reference to a people in the north of

Britain about the same time as the information of Ptolemy's geography

of Abion and Hibernia!)

The soft form of BIGDI is

significant in that Finnic language tends to be softer. (T is more like

"D", P more like "B", K more like "G", unless these are all doubled).

If we interpret it with Estonian, it could have a simple meaning

'(people) of the catches' (ie catches of fish, etc) which in

modern Estonian would be püükide

("pew-kee-deh"). (Supporting the

presence of such a word in western Europe is the French word for

'catch' pêche) It seems

reasonable that during Roman times, the

northerners would come south to sell their catches at markets, and,

since the catches from the sea were the major product of the north, all

the northerners could have eventually acquired the general description

of 'people of the catches'. One of the problems faced by people

trying to make sense of the Picti word, is that in Caesar's time the

peoples south of the mouth of the Loire were called the Pictones. That

was the reason Mowat in his Farfarers

assumed that some of the Pictones

migrated north

with some of their neighbouring Veneti, and that was where the name

came from. But if the name had a descriptive meaning, the two names

could be a coincidence: both fished and both assumed a name that

described that activity.

The Venerable Bede, said also that

the Picts came "in longboats from Scythia". We can read this part of

the legend in the following way: The people identified as Picts were

seen in Bede's time to recieve long distance traders arriving in

longboats, and it was observed the Pict language was similar to that of

the visiting traders. It was established that these visitors came from

"Scythia", and thus the deduction was that the Picts had originated in

the same place.

In Greek times "Scythia" referred to all the

lands north and west of the Black Sea, but by Roman times only the

northern parts remained "Scythia", the southern part becoming

"Sarmatia". By Bede's time "Scythia" would have been understood to be

the lands to the east of the east Baltic coast. Since all the peoples

with boats and engaged in trade in "Scythia" were in Bede's time (a

century or two before the Vikings), Finnic (Estonians, Livonians, etc)

, we conclude that the Picts to which Bede referred were those who were

part of a trade network, and who recieved goods from the east Baltic

coast. Given that to the west of the Rhobogdi

Ptolemy shows Vennicni,

we can presume that the Vennicni

name is a corruption of Vennicones

in

Ptolemy's Albion near

Aberdeen, and that these are identifiable with

the trader-Picts who were part of the Veneti/Venedi

world of traders.

Thus we see two groups identifiable with "Picts", the sea-harvesters

who only fished, and the traders who maintained trading posts and

warehouses and awaited the arrival from time to time of a longboat with

goods. Within these two groups, the level of primitiveness, or

civilizedness, varied too; however I believe that in general, the

larger populations in the south generally saw the north as the region

of the "(fish) catchers" in much the same way that in North America,

the eastern coast is generally seen as the regions of "fishermen" , or

the "fishing industry" even though much else is going on there too.

In his description of "Picts" Bede was

probably describing the

more visible trader-Picts, descendants of VENNE traders, not the less

visible Picts out at sea, and living on islands and coasts. The

sea-harvesters would rarely have been encountered by farming peoples,

and the VENNE traders served as intermediaries in any trading contacts

between them and the farmers to the south(Celts, Saxons, etc). The

trader-Picts, as

stated, may have been people of a Baltic-Finnic nature, hence the

connection with "Scythia" behind the east Baltic. But the

sea-hunter-Picts could have had another dialect, more like the dialect

of the Norwegian sea-hunters. Or indeed, something like

the Greenland Inuit, if we include them among the North Atlantians.

Mowat, in reviewing Bede's story said

that it was a reference to the Scilly Islands at the southwest tip of

Britain. But this presumes Bede was confused about what "Scythia"

really meant - which is impossible as everywhere in Latin texts

"Scythia" is east of the east Baltic (Finnic) coast. Where then does

"Scilly" come from? In Ptolemy's geography, not far from their

location the name Uxella

appears. I suggest that the Scilly Islands

were originally called "Uxella

Islands", and the modern name "Scilly"

is a corruption of that over the centuries. ("Uxella" via Finnic

suggests a combination of uks

and -la giving 'place of the

door, port'

which reminds us once again of the deep Finnic aboriginal nature of not

just Scandinavia, but also the British Isles.)

The end of both the seagoing

"Finns" and the "Picts" came around 1000AD, as a result of the conquest

of the Norwegian coast by the Danish kingdom, and then the expansion of

the Celtic Scots into the Pictish north. The dominant culture

eventually takes over.

Memories of "Finns" visiting the Shetlands, or

accounts of dark-complexioned "wild Irish" (as the illustrator of the

curragh called them), may represent the last witnessing of these

peoples in the British Isles. After civilization arrived in the British

north, there was a new breed of fishermen, who lived in settlements,

did farming or kept sheep and goats on the side, etc. They weren't real

sea-people, forever migrating seasonally from camp to camp. They were

now land people who had a permanent settlement and went to sea now and

then.

Most references to ancient British, whether

they were called peoples of Britannike

or Albion, referred to the

highly visible localized and settled peoples of the British mainland.

They did not refer to the sea-going peoples with their skin boats who

inhabited the outer islands and coast, and appeared to observers only

at coastal markets. Thus these sea-people are relatively invisible in

the historical records made by visiting Greeks and Romans.

SUMMARIZING

THE STORY OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLES OF THE BRITISH ISLES

I think that there was in the British Isles ALWAYS

the dicotomy of peoples, the peoples of the land territories and the

peoples of the surrounding seas. And because they lived in such

different environments they did not interract very much, and were

therefore ethnically somewhat different, although ultimately both were

of the same origins in the northern aboriginal boat-peoples or

water-peoples in general.

When the British Isles were invaded by the

Romans and the Celts, the only escape the sea-hunters of the British

Isles had from the aggressors, was to simply sail away, find a new

place to live that lacked the ugly Europeans. Some may have migrated to

Canadian shores. It is interesting that according to archeologists the

natives who were called called "Beothuks" appeared in Newfoundland

around about Roman

times. Interestingly, when Portuguese captured some into slavery in the

17th century, there is one record that stated that they resembled

Portuguese except a little taller and better built in the upper body.

Were they Picts? Where they refugees from Roman expansions into the

British north? Was the name "Beothuk" a variation of the name of the

Picts? (In Estonian püüde or

even peode means 'of the

catching'; also we note that Ptolemy

identifies a tribe named Epidi)

Pure common sense alone suggests that aboriginal seafarers

landed on the

Canadian coast of Labrador and Newfoundland numerous times in the past

6000 years, Any other view will ignore the fact that the aboriginal

seafarers were far more advanced than the Norse, already thousands of

years before the Norse. And if so then we

would expect that the cultures and languages of the peoples of the

Canadian arctic (Inuit) and of the forested regions below

(Algonquian-culture peoples), would possess in their language and

culture elements that can be compared with those of the Finnic-Uralic

world at the origins of skin boats, and more directly oceanic people of

the northeast Atlantic, historically appearing as skin-boat peoples

there, described as short people called "Finns" and in northern British

waters, "Picts".

The Basques as Southern

Descendants of Sea Peoples

I believe that all the Atlantic oceanic people

originated from the same

origins - the skin boat peoples who harvested the seas off the coast of

arctic Norway. That was their training ground. Once they had

mastered their way of life and their populations grew, some wandered

south, discovered the British Isles, and then with continued success,

some continued further south.

That brings us to the question of the Basques. The Basques

in recent centuries have been well known as harvesters of the Atlantic,

including whaling in the waters off the North American coast from as

early as the 16th century. It is easy to believe that they are

descended from the same world of oceanic seafarers as the Picts,

Norwegian "Finns", and the Inuit. One does not learn to be at home on

the waters of the Atlantic overnight. (Similarly the Portuguese have

the same origin, except that the coastal Portuguese have lost their

original language in much the same way as the original people of the

Norwegian coast did.)

The Basque language, is acknowledged to

be pre-Indo-European. Some scholars assume that the Basques are

descended from the original peoples of nearby regions dating back to

the cave people who left art on cave walls. However, we have to

recognize that there were two types of people during the

pre-Indo-European civilization in Western Europe - the seagoing people

and the interior people. The Basques display strong seafaring

traditions, and therefore it is reasonable to propose that they are

descended from the Atlantic seagoing peoples and not interior peoples.

This connection to seafaring in turn implies that

they are distantly related to Finnic and Inuit cultures, to the peoples

of the expansion of boat-peoples. While it is possible the Basques

learned whaling in the modern era, it is equally possible that the

Basques have always known whaling, and have had an ancient connection

with

peoples like the Greenland Inuit whalers. We don't know very much about

what the Basques did in ancient times.

In PART TWO we scanned the languages of whaling

peoples - Inuit and Kwakwala - and found many remarkable coincidences

with Finnic. What will we find if we scanned Basque words for

resonances with Finnic languages.

It happens that Basque indeed

presents

some words that can be interpreted with Estonian. Not too many -

otherwise linguists would already have made a connection common

knowledge - but it is there. If the Basques emerged from

oceanic hunters, then the linguistic distance between Estonian and

Basque would be less than

6000 years, dating back through arctic Norway and Lake Onega to the

"Kunda" culture. It

follows that we SHOULD find the same nature of similarities between

Estonian and Basque as between Estonian and Inuit, or other boat people

descended from the same "Descendants of KALLU" (See PART TWO).

A genetic connection between

two

languages cannot be proven by conventional comparative linguistic

analysis if the two languages are more than about 3000 years apart.

However the ability to find a great number of coincidences that are

unlikely to have been borrowed from a mutual third language, has

statistical significance. If there are coincidences better than what

would occur by random chance, conclusions can be drawn from it. Let us

do a short comparison of Basque and Estonian words.

COMPARING BASQUE AND FINNIC

Linguists have observed that the grammatical

structure of Estonian and

Basque are similar, having many case endings, for instance. Our

intention here is not

to make definitive linguistic discoveries, but to show that - along

with the other evidence - comparing Basque with Finnic does not

contradict our theory. In fact I think what we will find tends to

support it. It is what we would expect, given the Basques are so

sea-oriented.

I will focus on words: I used a mere 1000

common Basque words as the source, and my own basic knowledge of

Estonian words. I found that the majority of Basque words were

obviously Basque versions of Romance names, borrowed from many

centuries of influence from Romans and then French and Spanish. Thus if

we eliminate the Romance words, we greatly reduce the number of usable

Basque words.

From this limited word list I found a rate of

coincidence with Estonian that is much greater than random

chance. One has to recognize that the Basque words have to not only

resemble Estonian words but the meanings have to resemble each other

too. The probability of such double coincidence by random chance is

very low (See discussion of probabilities in PART TWO).

The remarkable parallels between Basque and

Estonian include the following:

Basque su

'fire',

compared to Estonian süsi

'coal, ember', süüta 'fire

up'; Basque oroi

'thought' compared to Estonian aru

'understanding'; Basque ama

'mother'

compared to Estonian ema

'mother'; Basque uste

'believe' compared to

Estonian usk 'belief', usu 'believe'; Basque ola 'place' vs Estonian

ala 'field (of endeavour)';

Basque kale 'street' vs

Estonian kald

'bank, shore' (ie original streets of boat people were rivers, shores);

Basque ke 'smoke' vs Estonian

kee 'boil'; Basque leku 'space' vs

Estonian lage 'wide open

(place)'; Basque hartu 'take'

vs

Estonian haara 'grab hold';

Basque ohar 'warning' vs

Estonian oht

'danger'; Basque tira

'pull' vs Estonian tiri 'pull

away, pull loose';

Basque gela 'room' vs

Estonian küla 'living place,

abode, settlement';

Basque lo 'sleeping' vs

Estonian lÄbeb looja '(it,

like the sun) sets,

goes down, goes to sleep'; Basque marrubi

'strawberry' vs Estonian mari

'berry'; Basque txotx

'twig' vs Estonian oks

'branch''; Basque ohe

'bed' vs Estonian ase 'bed';

Basque osatu 'complete' vs

Estonian osata

'without any part''; Basque or, zakur

'dog' vs Estonian koer 'dog';

Basque jan 'eat' vs Estonian jÄnu 'thirst'; Basque jarraitu 'continue'

or jarri 'become' vs Estonian

jÄrg 'continuation', jÄrel 'remaining,

to-come', etc; Basque giza

'human' vs Estonian keha

'body'; Basque

haragi 'beef/meat' vs Estonian

hÄrg 'ox'; Basque izen 'name' vs

Estonian ise(n) 'of

oneself'; Basque lau

'straight' vs Estonian laud

'board, table' (ie straight piece of wood); Basque lasai 'calm' vs

Estonian laisk 'lazy' or lase 'let go'; Basque ezti 'honey' vs Estonian

mesi 'honey;

Basque is considered to be descended

from the people the Romans generally called Aquitani, located mainly in

the Garonne River water basin as far as the Pyrennes mountains.

Aquitani in fact implies

'water-people'in Latin. The name may have been inspired by

Uituriges or Uitoriges ( Caesar Gallic Wars, I,

18) the name of a

people who controlled Burdigala

the town on the lagoon formed by the

outlets of the Garonne River. The word Uituriges or Uitoriges resembles

Estonian/Finnish because the the first part corresponds well with UI-

words meaning basically 'swim', such as Estonian uju, Finnish

uida. The latter part of

Uituriges, is the word meaning

'nation'

(as in Estonian riik, riigi),

hence the name Uituriges

means 'floating

nations'. An alternative name for them in the historical record was

Bituriges. If this was a true

alternative name, then we should look to

BI in the meaning of 'water', and the full word paralleling modern

Estonian Veederiigid, meaning

'water-nations'. This latter version

would be the most applicable inspiration for the Latin Aquitani. I

believe in a pre-literate world where people and places were named by

describing them, that it is possible BOTH versions Uitoriges and

Bituriges were used.

The most interesting word in Basque from the

point of view of sea-peoples is the word for 'water' which is ur.

This word exists, in my view, in the name "Uralic Mountains".

Perhaps we can allow ur

to an abbreviation of UI-RA.

The -RA is a widely used element of the ancient world, appearing in

association with travel-ways. Furthermore, the Basque allative case

ending (motion towards) is -ra.

Combining this with the appearance of

UI in the historical name Uitoriges,

suggests it is possible Basque ur

is ndeed an abbreviation of UI-RA, 'the way of the floating,

swimming'. It

obviously did not view 'water' originally as the liquid but as the sea

over which the seafarer travelled.

The Basque word for 'earth' appears to add an

L to ur producing lur. But it is more likely from

ALU-RA,

'land-territory path'. ALU (Estonian alu

'base, foundation, territory')

is reflected in Basque ola

meaning 'place (where something is done)'.

Thus here once again the Estonian interpretation mirrors something in

Basque, indicating too that Basque and Estonian were closer at an

earlier time. The chances of the Basque lur being based on ALU is

supported by the fact that in Roman times the stem ALU occurs several

times, especially in the Roman name Albion

but more clearly in the

Greek Alouiones (read

ALU-AVA-N). If the native British used ALU or ALO

'land-base', 'territory' as the stem for some geographic names, then we

can expect that the ancestors of the Basques did too, since in

seafaring terms both places were part of the same early Atlantic world.

SUMMARY:

ABORIGINAL SEAFARERS IN THE EAST ATLANTIC

While the theory of an eastern north Atlantic

aboriginal seafaring people who moved with the currents in a circuit

that touched the coasts of Norway, Iceland, Faeroes, Shetlands,

northern Britain and back to Norway is undeniable, and it gives us a

framework for interpreting historical accounts about "Finns" in the

ocean.

But as we look southward, the millenia of

involvement of civilization, has made it more difficult to interpret

early events in the British Isles and southward.

The only clear whaling peoples in the east Altantic

are the Basques. Basques are today modern people and it is difficult to

find the evidence of the deep past. But there are two ways of doing so.

First of all a people so dedicated to the Atlantic ocean, and to