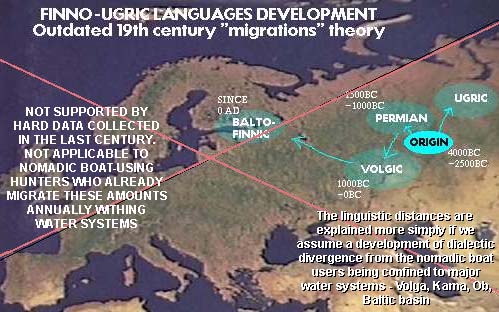

Map 1. This theory has been around so long that there has been a

tendency to revise it (mainly to change the date of arrival at the

Baltic), rather than throw it out, until recently.

There has never been a problem with the comparative

linguistics determinations themselves. The problem has been in applying

it to describe the real events.

Linguistics has decided on the existence of a large superfamily

of "Uralic" languages of western Eurasia, which have a basic

subdivision between the "Samoyeds" and "Finno-Ugrians". The former

refer to peoples in the high arctic, originally reindeer hunters, now

herding them, who have strong arctic mongoloid racial features. The

original studies concluded from linguistic distances that an

original "Uralic" language family split into the "Samoyed" language

family and the "Finno-Ugric" language family. There is nothing

wrong with seeing these two groups having roots in the same prehistoric

language. The issue is how the languages, dialects, drifted apart.. The

original tight-origin theory assumed a tight origin in the

vicinity of the Ural Mountains around 6000BC, and then the original

parental "Finno-Ugric" language started to subdivide and subdivide,

with each breakaway group migrating elsewhere. See the above map. The

problems with this theory are countless, notably, when one takes into

account the far-ranging nature of boat-using hunter-fisher-gatherers

such as found in Canada in around 1600.

Back when the original

tight-origin theory was being developed it appears only one

contemporary linguist was intelligent enough to realize something was

wrong. In 1907 Heikki Ojansuu expressed the view that "the F-U peoples

once occupied a broad zone extending somewhere from the region of

Ilmajärvi, then along the Volga and its tributaries to the region of

the Kama and the Urals" He believed that hunters and fishermen needed

large areas for their activities (Heikki Ojansuu, Oma Maa, 1 (1920),

318-328). Later another Finn, Paavo Ravila noted, but did not realize,

the solution of simple dialectic differentiation, that the geographical

distribution of the F-U languages closely reflected their relationship.

Later, another Finn, Erkki Itkonen, proposed the conflicts the original

linguists' theory had with archeology (that found no evidence of

migrations) could be reduced by assuming the F-U peoples occupied the

entire area from the Urals and the Baltic from time immemorial.

(Itkonen, Oma Maa, 1958) Toivo Vuorela summed this line of thinking as

follows (Vuorela, The Finno-Ugric Peoples Eng. trans. J. Atkinson,

1964) "In this sense [Itkonen] refers to Ojansuu's idea of an 'unbroken

zone of peoples' from Ilmajärvi to the Urals, and to Ravila's view that

the geographical distribution of the F-U languages reflects their

relationship. When the once food-gathering peoples, who had needed wide

areas in which to move about, became agriculturalists and so were more

inclined to stay in one area, 'the various groups that were accustomed

to live together became virtually frozen to the spot in their former

hunting grounds' -- and thus dialects became more and more separate and

over centuries and millenia developed into separate languages.

The idea of hunting people 'being frozen

to their former hunting grounds' is interesting from the point of view

of the Estonian and Finnish words for 'family' pere/perhe . It is

possible that this word originates from PEO-RA (ie, pida +

rada) meaning 'hunting,trapping, catching + trail, way,

road' suggesting that each clan had their own hunting

territory of trails, something confirmed among Canada's Algonquian

Indian past; so that when they had to settle down, the hunting trails

disappeared so that all that was left was the clan, the family, the

PEO-RA, or pere/perhe.

Another issue was whether Finno-Ugric

languages existed to the west of the Baltic, since no Finno-Ugric

languages survived there by the 19th century. Clearly had a Finno-Ugric

language or two survived in Sweden or Britain, as proof, all the

thinking would have taken another route. (History in Norway and Sweden

speak of 'Finns' on coasts, in the forests and on the tundra, and

scholars commonly assume that it means the Saami,(Lapps).

Still, here too, there was one scholar

who took another view than the tight-Ural-origin theory. The

German Gustaf Kossinna tried to place the F-U homeland in North Germany

and Scandinavia (Mannus, I-II Mannus Bibl. 26 (1909-1911))

Interestingly, there is a suggestion in the Estonian folk epic

Kalevipoeg that (assuming the part I will refer to is from original

folklore and not invented by the compiler) there was, perhaps back in

the Viking Age, Finno-Uric speakers in Norway. In the story, Kalev has

three sons, one becoming Kalevipoeg, the hero of Estonian and Finnish

folklore, another going to Russia to become a merchant (referring

probably to the Votes and others who carried on trade to the Dneiper

and Volga) and the third to Norway to "become a warrior". It is clear

that the intent of the folk legend was to acknowledge all obviously

related Finnic peoples, as they would obviously have had the same

parent - Kalev(a). This last Norwegian warrior character is interesting

because it was during 800-1000AD that Danish kings were on a campaign

to bring Norway into their kingdoms. Thus for two centuries southern

Norway and up its coast was a region of conflict, requiring soldier

assistance. It follows that around 800-1000AD, Estonians would have

perceived there to be a related people always at war with the Danish

armies, and hence the legend-maker included a son of Kalev who was a

warrior/soldier in Norway, in order to give an origin to a

Finnic-speaking people in southern Norway. Historically Norwegian

and Swedish documents speak of the aboriginal peoples - not just the

reindeer people, but those on the coasts and in the forests, - being

'Finns' and that the name 'Finland' was a Swedish creation, as the area

now Finland belonged to Sweden. One can say 'Well they were

people related to the Saami (Lapps)' and that might be alright, if the

Saami spoke a language very different from Finnish, but the fact is the

Saami language is so Finnic in character, that linguistics includes it

in the Finno-Ugric and often even in the Balto-Finnic languages. It all

suggests the better view is that the Saami and Balto-Finnic language

are related and that what separates them is only the level of

development towards civilization, the more southerly ones (Finnish,

Estonian, and extinct ones further south) adapting more and faster to

the agricultural civilization pushing up from the south, while the

northernly ones (Saami) remained relatively primitive due to greater

isolation.

Furthermore, should we put up the

western boundary at Scandinavia? Since archeology indicates trade

connections between Norway and northern Britain (ie the Picts), we can

extend the Finno-Ugrians even to the Picts, at least those of the east

side. The connection between the trader-Picts and the east Baltic is

affirmed by the Anglo-Saxon scholar monk Venerable Bede who wrote in

his famous history of Britain, that the Picts had come in longboats

"from Scythia". In that day, "Scythia" was the region from the east

Baltic eastward. Clearly traders from Greater Estonia were arriving on

the British east coast, and were witnessed to speak a language similar

to that of the Picts who recieved them.

Thus alternative views that are now

proving to be more correct, have had early precendents among scholars;

however individual voices were drowned out by those who promoted the

tight Ural origin, and successions of migrations westward.

The New View of the Languages of the Boat Peoples

Already from about the 50's archeology, failing to find any evidence of

east-to-west migrations or a tight homeland, took issue with the old

theory. Noted Estonian archeologist Richard Indreko, for example wrote

that the archeological evidence, on the contrary, showed a movement of

archeological culture the other way - from west to east. But the

tendency was to revise the old theory, than to dispose of it.

Archeology showed an east to west movement of pottery with comblike

markings. Maybe that showed the migration, some said. Richard Indreko

addressed this suggestion by pointing out that the movement of a

cultural feature does not mean migration. It can mean simply the

movement of a new cultural practice through contacts between related

Finno-Ugric tribes. Later it could be the result of trade.

But nobody pointed out the

main problem with ANY migration theory: the nature of the life of

boat-using hunter-fishers. Living in Canada, I became interested in the

Algonquian aboriginal peoples, who lived a similar life as

boat(canoe)-travelling hunter-fishers, in a similar northern

environment. I saw in them a good model for ancient Finno-Ugric

language development. In this Algonquian language family, the

linguistic divisions - as Europeans found them in the 16th century -

were according to water basins, a different language in a different

water basin, with the larger ones having dialectic subdivisions. This

is because they moved around in canoes. They were boat-people. People

who are dependent on boats not only travel some five times further than

people on foot, but they will tend to remain within the water system

where the boats can travel. Thus each water system would tend to

form its own dialectic subdivision of the larger culture. In a sentence

far-ranging seasonally nomadic boat-using hunter-gatherers were not

localized, but were naturally constrained by where their boats could

easily go, constrained by water basin boundaries.

When Europeans arrived in he

17th century they found that there were the Cree in the water basin of

the Hudson Bay, Ojibwa in the water basin of the Great Lakes,

Algonquins in the Ottawa River water basin, Montagnais Innu in the

Saguenay River water basin, and Labrador Innu in the Churchill River

water basin. I haves shown this on a map of North America below.

Map 2. The Algonquian native peoples of the forested region of the

east quadrant of northeast North America, were boat-using hunter-fisher

gatherers who lived a seasonally nomadic life. Their language divisions

are related to water basins, and the best explanation for their history

is that there was a rapid expansion up all the rivers from the

Altantic, that filled up the lands, and then gradually dialectic

divergence occurred according to boat-use being confined to water basin

regions.

When we apply this to northern Europe, to the entire region that

archeology demonstrates was inhabited by boat-oriented hunter-fisher

peoples, we arrive at a map like this:

Map 3.The Finno-Ugric origins are best viewed in boat-using

hunter-gatherers in a similar environment, and their language family

divisions also are related to water basins. The Finno-Ugric

subdivisions are however older, as the languages have further

subdivided as a result of people settling down into farming. But the

ancient situation, resembling that of the Algonquians, is evident. Note

that if the Finno-Ugrians extended further west, there once were other

dialectic regions for example in the Vistula and Oder River water

basins.

The above map shows that the Finno-Ugric language

subdivisions too are related to water basins (Baltic, Volga, Ob, etc),

, so that the it is clear that there were no migrations, but rather the

constant movements of seasonally nomadic boat-peoples, who were

nonetheless constrained to water systems so that linguistic distances

developed according to the natural separation of boat peoples by the

water systems in which they moved

In short, the languages developed in the

same way as dialects--by an original language covering a large area,

and geographic circumstances causing localization. (And later in

history as the nomadic Finno-Ugrians settled down to farm, each of the

basic water-system dialects began to subdivide further between one

farming area and another.)

additional discussion: influences from reindeer peoples

In the real world, nothing is every this simple. In

the Algonquian example, there was influence from the Inuit languages of

the North American arctic, and from the Iroquoian languages of the

lower Great Lakes. These languages would mainly have influenced the

dialects next to these other peoples, but too weak for the influences

to affect the entire wide distribution of these boat people languages +

unless of course the influence is very strong and lasts millenia!

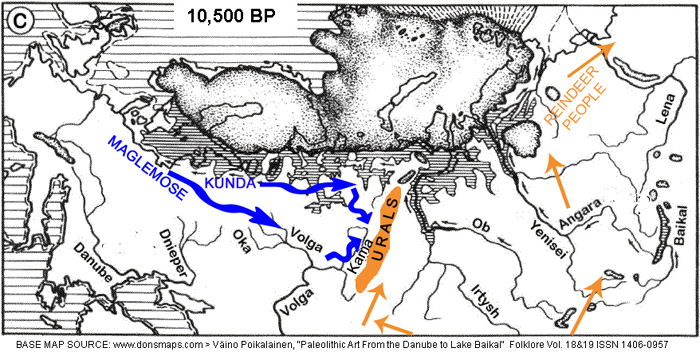

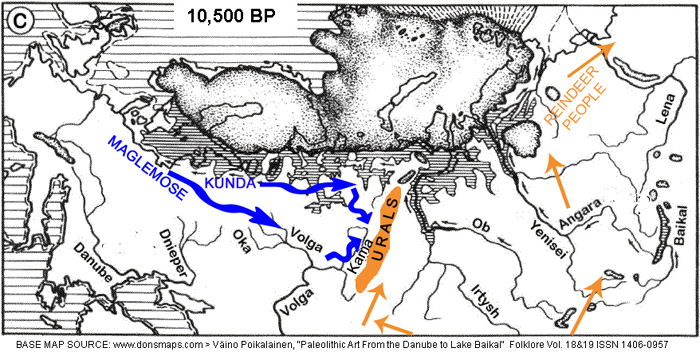

The same is true of the expansion of the language of

the European boat peoples that arose from the archeological "Maglemose"

and "Kunda" cultures around the south and east Baltic.The following map

shows what had happened by about 10,500 Before Present. Note how the

Volga-Kama and Pechora water systems came close together about the

midpoint of the Urals. It is highly probable that there was a meeting

place there - meeting to trade, socialize, find mates. It would have

been there that reindeer people in the Urals would have influenced the

language of the boat peoples arriving there.

Map 4 The base map underneath the added information comes from a

scholarly article in the publication given in the text below the map.

Few maps showing the retreat of the glaciers bothers to show the

regions flooded by glacial meltwater, that today appear as coastal

marshlands. I was very pleased to find this map, because the

locations of flooding is very important to our discussion of both boat

people and reindeer people, because boat people find water as

beneficial, while reindeer cannot survive in flooded lands, even in

winter because reindeer need to find their lichen food underneath the

snow. This map actually shows why the "Kunda" culture would have easily

expanded east - they only needed to follow the glacier lakes. And it

shows why any N3 reindeer people at the north end of the Urals would

not have been able to migrate west to northern Finland for several

millenia and modern coasts and tundra had appeared. It is recommended

the reader interested in this, investigate paleoclimatology to

understand both the expansion of the boat peoples, and the shrinking

ability for reindeer to find anywhere to survive, other than the arctic

Siberian coast, which we can see had no glaciers or glacial lakes.

At this early time, the regions formerly covered by the Ice Age

glaciers were completely new and vacant, or where previously the land

was too cold (like today the interior of Antarctica). Boat

people expandng into the new flooded lands did not

encounter any other peoples or languages

until some reached the vicinity of the Ural Mountains.

According to archeology, a culture that looked like

the "Kunda" culture appears to have reached the Pechora water basin. At the

same time another boat people, which I think can be identified with the

"Maglemose" culture went north from the Volga to the location where the

Pechora, Kama and Ural Mountains are close together.

In locations where the territories of different peoples come close to

each it was the practice of northern aboriginal peoples - and

there are many examples in northern North America - of the development of

significant gathering places where the normally scattered people can come together to

socialize, find mates, and trade. From logic alone, there was

convergence between languages and cultures at such locations.

The map above shows how the blue arrows of the boat

people reach the Ural Mountains in about the middle location where

archeology shows there were hunter-gatherers of a different culture.

Recently the new science of population genetics has discovered that men

of reindeer peoples across the Eurasian arctic possess the highest

concentration of the Y-DNA N-haplogroup. It appears to have travelled

north from about 15,000 years ago. It is obvious that this haplogroup

originated with reindeer people in the Ice Age, and then moved north

with the original Ice Age reindeer herds as the world climate warmed.

While the N2 version of the N-haplogroup is easy to understand because

it dominates the Tamir Peninsula Samoyeds, the story of the N3 version

(today called N1b) is complex as it ended up in highest concentrations

in the Yakuts of northeast Siberia, and the Saami and Finns of northern

Finland. (From these locations the haplogroup radiated outward as men

carrying it moved out into surrounding territories, often abandoning

their original reindeer-oriented way of life. The explanation for the

division of the N3-halogroup into Saami and Yakuts, thousands of km

apart, was solved in 2006 by Rootsi et al. (Rootsi,S., et al.

2006,

A counterclockwise northern route of the Y-chromosome haplogroup N from Southeast Asia towards Europe”

European Journal of Human Genetics 15 (2): 204-11) In that study,

the conclusion was that the N3 (N1b) haplogroup originated around

12,000 years ago in southwest Siberia, south of the Ob River water

basin. Here the men divided into two - one group turning east, and the

other group turning west. In my opinion, since reindeer cannot survive

in the marshlands of the Ob River water basin, the reindeer had to go

around it, and then continue north either through the Central Siberian

Plateau or the Ural Mountain range.

According to Rootsi et al, the N3 (N1b) haplogroup

that went west, turned north and went through the Ural Mountains,

becoming established about 10,000 years ago. And then later it

migrated west along the arctic coast to northern Finland, and from

northern Finland diffused south. The reason for that route is

simple - it followed the movements of reindeer herds. The reindeer had

to travel north in the Urals, because further west was too hot and

marshy. Next the reindeer had to travel along the north coast of

northeast Europe also in order to stay in the cool tundra, but only

when the glaciers and glacial lakes had disappeared.

The connection of the N-haplogroup to peoples who

were dependent on tundra reindeer herds is so obvious, that those

scholars who claim the N-haplogroup entered the Finnic boat peoples, is

ridiculous. Other than the Saami, the Finnic cultures and language are

dominated by imagery related to boat use and wetlands. There is nothing

connected to reindeer. It follows that the N3 haplogroup entered the

Finnic peoples simply from reindeer people in northern Finland,

departing from their original reindeer-oriented life, and entering the

much more flexible and adaptable boat-oriented hunter gatherers. Once

they had changed culture, the far ranging nature of boat use quickly

spread the reindeer-hunter haplogroup southward.

Since the migration southward of the N3(N1b)

haplogroup would have been motivated by moving from the

reindeer-oriented culture to the boat-oriented hunter-gatherer culture,

those who converted to the boat people world, would quickly have

adopted the language of the boat people.

Conclusions: Language of the Boat Peoples probably at roots of Finnic

Archeology has always

suggested the obvious - as the climate warmed after the Ice Age,

culture expanded out of Europe into the east. Now the new genetic

studies also suggest that Finno-Ugric speaking peoples are basically

Europeans. Thus it is only now that Finno-Ugric languages and

traditions are being considered in terms of the history of Europe. It

is now easier to accept that the Finno-Ugric languages originate from

the original boat-oriented hunter-fisher peoples of northern Europe.

But many are unable to grasp the nature of these people. But a good

picture of them can be had by considering the nature of the Algonquian

natives peoples of northeastern North America - a people who were

similarly nomadic boad using hunter-fishers, and similarly lived in a

northern wooded region filled with waterways. In addition

we can see how European civilization has affected them from south to

north since the 17th century. It is easy to see that the same thing

occurred in Europe, except at a much slower pace, as technology and

population growth in the civilized parts of Europe were not advancing

at the same pace as in the last centuries.

Let's review what has happened

here in North America. North America was overrun by Europeans from the

17th to 20th century, and history plainly shows the manner in which it

affected the original native peoplesnbsp; Basically the European

settlers were farmers; thus the regions where the native peoples were

displaced or assimilated first were first those areas which were ideal

for farming. Marshes, rocky hillsides, acidic rocky soils,

mountains and cold northern climates were places where the

European settlers did not immediately go, and native tribes found

refuge there. Gradually European settlers pushed into poor lands too,

so the native peoples then could only survive in the VERY poor lands,

particularly in the remote north.

Today, native language and culture

survives most strongly in Canada, primarily because of the cold

northern climate that resists being farmed. While in the United States,

only small pockets of native cultures can still be found (desert areas

having more of them), in Canada the entire north part of Canada is

strongly populated by native cultures, that is, by peoples who still

identify themselves as native and even speak their own language (Cree,

Dene, Inuit, etc).

Scholars in North Americans, faced with

the question of the evolution of Europe, therefore are more inclined to

accept a theory that perhaps the Saami and Finns of northern Europe may

similarly be remnants of the original native people of Europe. It is

almost obvious. But scholars do not think broadly enough. What is

required is to imagine the nature of aboriginal peoples across the

entire northern Europe, then being influenced by the arrival of new

cultures, new practices, starting with the regions most suited to

farming. We are not merely dealing with the extinguishing of the Saami

in the Scandinavian Peninsula, from south to north - surviving today

only in the most remote north and in the mountains of Norway - but of

northern Europe as a whole. How can we draw the line just at

Scandianvia? These were boat peoples descended from the Maglemose

culture - water was not an obstacle: quite the contrary water

facilitated their movements and expansions, and it is clear that these

people expanded east and south, wherever waterways were found to carry

them and their dugout (or in the north- skin) boats.

If it has been

happening in Canada with respect to the Algonquians, assimilated from

south to north, then why do we not apply this truth to early Europe?

Possibly it is because scholars in Europe cannot grasp it as well as

scholars in North America, especially in Canada.

Thus the plain fact that

farming cultures displace native hunter-fisher-gatherers from south to

north, and from fertile higher lands to poor acid marshlands, leads to

the conclusions that it is possible that indeed the ancestral language

of the Finnic peoples was the original language of continental Europe.

What other candidates are there? And even if there was movement

of culture according to waterways - since all these peoples wandered

seasonally over wide areas - then that represents cultural influence in

the natural course of contacts, not of any kinds of permanent

migrations. We are not talking about farmers, who have to pack up

wagons and migrate. We are talking about peoples who in the northern

world were clans who were already annally covering an area the diameter

of several hundred kilometers, and tribes (groups of 4-6 clans)

whose total diameter could be 1000 miles (The reach could have been

even more if elongated - as with coastal peoples). All that of course

came to an end wherever these peoples established a permanent

settlement, even if they remained primarily hunter-fishers; and when

they became primarily farmers, their range reduced right down to a

radius of maybe only 50 km.

The old linguistic theory on the

origins of Finno-Ugric languages, in describing their origins in a

tight location near the Ural mountains, has done the world of

scholarship a great disservice. For over a century scholars have

completely ignored the Finno-Ugric languages in investigations of

prehistoric Europe simply because they have been told they were not

there, but in the east.

Well all the evidence shows that

the origins of the Finno-Ugric languages were not only in continental

Europe but represent the aboriginal foundations of Europe. Farming

cultures, and eventually Indo-European cultures came into Europe in

waves, and converted the natives in much the same way as European

cultures did in North America since the 16th century. Note that in

later history, there were no migrations, but rather military conquest,

beginning with the Roman conquest of Europe and establishing the Roman

Empire. When the Roman Empire collapsed, Germanic and Slavic powers

adopted Roman methods of conquest and rule, and that is the main reason

the regions originally Finno-Ugric in nature are now speaking Germanic

or Slavic languages. The fate of the Finno-Ugric cultures is the

same as as that of the native peoples of North America, absorbed into

the new cultures introduced by new settlers, or imposed by military

conquerors, except in the regions most remote from the thrust of

civilization. The only different between North America and Europe is

that it occurred much more gradually in Europe.

additional discussion: little influence of reindeer people language on the boat people

The addition of the N3 (N1b) reindeer people considerations may

have affected the boat people dialects at the

contact location where the Pechora, Kama water basins and Ural

Mountains meet, and the later contact locations in northern

Finland, but most of the region of boat peoples far from these

contact locations was not affected.

Because the Ob-Ugrian languages are much more like Samoyedic

than the Finnic languages to the west of the Urals, today some

linguists wish to consider the Ugric languages (Ob-Ugrian lanuages and

today's Hungarian displaced south by the fur trade) to more

properly belong to the Turkic languages. It is significant that

the linguists consider the language of the Yakut reindeer peoples to be

"Turkic". Reindeer people called Duhka in the southern Siberian and

northern Mongolian mountains have a language also considered Turkic. Is

it possible the Samoyedic and Saami language is also Turkic. but was

more influenced towards Finnic, than the reverse.

In general when two

languages come in contact, the language of the stronger culture will

have more effect on the other language, and throughout the period of

retreat of the glaciers and the warming of the world climate, the boat

people dominated. The climate warming between 15,000 years ago and

10,000 years ago favoured the boat peoples since they were adapted to

flooded and forested lands. At the same time reindeer people were

compromised as the tundra reindeer herds disappeared. The

original way of life that harvested large tundra reindeer herds

disappeared. Ex-reindeer people had to hunt individual woodland

reindeer, moose, elk, and aquatic animals, and move around a marshy

landscape with boats. In general, ex-reindeer peoples all joined the

boat peoples, and that explains why Finnic people possess the

N3-haplogroup and also some mongoloid characteristics in their faces -

they include reindeer people who joined the boat people when the

original reindeer culture collapsed other than a few refuge locations.

Personally I have no objection to the reindeer

peoples languages being dropped off the grouping of boat-people

languages, and for

linguists to put them into an improved "Turkic" language family,

putting reindeer peoples languages close to its roots. The reason is

simple: the tradition of hunting and managing tundra reindeer herds is

so completely different from the original boat-oriented

hunting-gathering way of life that it is difficult to imagine mixing

the two. In fact, in the larger picture, according to archeology,

the "Maglemose" and "Kunda" cultures arose from the north European

reindeer people who then became extinct. Tundra reindeer culture

is therefore many thousands of years older than that of the boat

people, and have a history all its own before anyone even thought of

moving around in a flooded landscape in boats.

2016 (c) A. Pääbo. UPDATED 2016