www.paabo.ca

- A division of the

UIRALA boat peoples theme-

STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT BOAT

PEOPLES EXPANDING INTO THE ROLE OF LONG DISTANCE TRADE 2000-0 BC -

(most referred to as "Veneti")

Note: These studies deal

with only the ANCIENT , pre-Roman, pre-Indo-European, world of long

distance trade. After the Roman Age, major changes caused by the Roman

Empire brought the original trade systems to an end, and the original

pre-Indo-European Veneti became localized (adopting the language of

their smaller regions of activity), and the original pre-Indo-European

Veneti disappeared, just as the Phoenicians and other original peoples

of the trade world disappeared.

This is important to understand since

there exists today plenty of confusion as a result of post-Roman Veneti

speaking Latin in northern Italy, Slavic in Eastern Europe, Celtic in

northeast Europe, and even Germanic in central Europe.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARGUMENT AND

EVIDENCE THAT THE ANCIENT, PRE-ROMAN, LANGUAGE IN NORTHERN ITALY WAS

FINNIC IN NATURE AS A CONSEQUENCE OF NORTH-SOUTH TRADE IN TIN, AMBER,

AND FURS

THE LANGUAGE OF THE ANCIENT

VENETI

A New View of the Language

in the

Ancient Venetic Inscriptions

by Andres

Pääbo

Ancient Veneti, also called Eneti by ancient Greeks,

occupied the regions northwest of where Venice is today in a wealthy

society with - as one ancient text said - 50 cities.

In this society, made wealthy by trade since the land was not all

that good for farming, writing was adopted. Borrowing and

modifying the Etruscan alphabet, they wrote sentences on objects, and

archeology has found several hundred examples of writing surviving on

durable materials, although less than 100 are complete and not

fragments. Scholars have for centuries wondered about the

language in the inscriptions and sought to decipher them. Lacking

any example of writing that was accompanied by a translation in a

known ancient language like Greek or Phoenician, scholars simply

advanced blind hypotheses about the linguistic nature of Venetic

and then testing the theory. The following article

introduces a new approach that , like archeology, is not focussed only

on the actual writing, but draws information from the context of

the inscriptions both in the object use, and on the larger scale

of the situation in Europe in those times, such as trade patterns

and the prevailing languages . This article is a summary of the

core content of

THE

VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language

from a New Perspective: FINAL

a book of almost 1000 pages that documents a major project by the

author to interpret Venetic inscriptions in a more direct

manner with later consideration of Venetic being Finnic.

The central methodology is to initially pursue results directly

from the contexts in which the writing occurs, and internal

comparative analysis such as finding consistency in grammatical

elements and word meanings. This article is a general introduction

to

THE

VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language

from a New Perspective: FINAL

and a good profile of it, to both allow the reader to quickly grasp the

ideas behind the larger document, and to decide whether to venture into

the larger document.

1.

INTRODUCTION

THE

ANCIENT VENETI CIVILIZATION IN ITALY BEFORE THE ROMANS

From the end of the 2nd millenium BC for a

thousand years until the Roman Empire, northeastern Italy saw the

flourishing of a civilization of ancient Veneti. These people, who

ancient Greeks knew as Eneti,

are mentioned as early as in Homer's epic poem about the Trojan War,

called The Iliad.

Even in ancient times, The Iliad,

written about 800BC, was thought to describe a war in Asia MInor that

occurred around 1200 BC. The Iliad

became popular and was thought to reflect actual events. By Roman

times, mythology had developed that imagined the Trojan War was

followed by the wanderings of Achaean and Trojan heros such as for

example Antenor. A tradition developed already in ancient times to try

to explain why the Eneti/Veneti name

was found at the north end of the Adriatic Sea. The Eneti

or in Latin Veneti, who had been allies to the Trojans, the story goes,

landed on the northern Adriatic coast, and settled there,

displacing the natives , the Euganei.

It is notable that it was promoted by Roman historian Livy, who himself

came from the regions of the Veneti in

northern Italy. Through the centuries since Roman times, this

belief has been taken to heart. Centuries later, at the time of the

rise of Venice and Venetian merchants, Venetian families drew up family

trees that placed heros of the Trojan War at the roots of the trees. It

was all fantasy. Archeology of the past century has not found any

support in the actual evidence in the ground to support this arrival

from Troy. Archeology does not find a sudden

displacement/.replacement of an original culture, but that the Veneti

markets and colonies developed gradually from mainly northern

influences. We can conclude that the theory of migration of Trojan

heroes was born from romantic thinking. What was the reality?

The archaeological record reveals that from about

1000 BC at the north end of the Adriatic there developed a new

civilization that covered a region that today comprises the

current Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia and Trentino locations.

Natural boundaries for this region consisted of the Po River to the

south, the Mincio and the Garda Rivers on the west, the valley of

the Adige to the north- west and the Alps to the north and

northeast. The region within these natural boundaries comprised a

large geographical area with a heterogeneous morphology that

included areas of plains, hills and mountains, and marshy regions. The

marshy regions were mostly found in the lowlands of the

Veneto-Friuli region bordering the lagoon . This was area includes

fertile plains and wooded areas crossed by major rivers. The location

of the Veneti civilization was strategic relative to central Euripe

towards the north, and the Mediterranean to the south. Archeology has

uncovered hundreds of objects attributed to the ancient Veneti

describing how they lived, procured food, buried their dead, etc. The

archeological discoveries have shed light on their culture, their

practice of writing and its link to the sacred universe, their mastery

of working bronze and expressing themselves in art and decoration.

The Adriatic (V)Eneti excelled in the working of

bronze into all manner of items. They made iron goods as well.

Metal goods ranged from practical tools like axes, hoes, shears and so

on to household items like containers, and of course arms of war –

shields, swords, helmets, etc.

Notable among the finds was the bronze container

referred to as a “situla”. The situlas were formed from two

sheets of bronze, combined and worked, and then stamped with the

designs. Like the containers made of ceramics, we can assume that

bronze containers had many applications. The situla and its decorations

followed styles with an affinity to their east rather than central

Europe to the north, demonstrating that there were trade connections to

Greece and beyond. While northern traders brought goods like Baltic

amber south, it was the colonies at the Adriatic who took the

distribution into the Mediterranean and thereby became influenced by

the cultures of their customers on top of what had been established

from the northern direction.

One of the most interesting archeological objects

from the ancient Veneti is that of a woman in a local costume. She also

reveals a particular hairstyle characteristic of Venetic women. Some

believe she depicts the Venetic goddess.

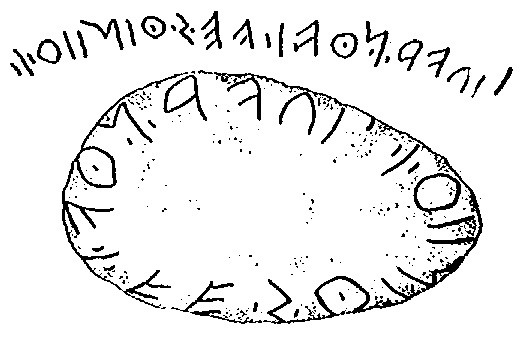

Votive

disc of Montebelluna, IV century BC. (Museo Civico di Treviso)

This

disc, it is believed, represents the Goddess, dressed in the Venetic

fashion of the day. The identity and relevance ot the animals on both

sides is worth further study.

There is much evidence that the Veneti,

even though they produced their own food and carried on metallurgy and

craftmanship, were mainly involved in trading activity. Goods were

constantly crossing the Alps on one side, and being shipped out into

the Mediterranean markets on the other. On the one hand there was amber

coming down from the Jutland Peninsula or southeast Baltic, and on the

other, traders ventured as far as the Caucusus in Asia Minor. Indeed

ancient Greeks identify the “Eneti”

name in Asia Minor. The "Veneti"

name moreover appeared by Roman times in northeast Europe in Brittany,

and in the form "Venedi"

on the Vistula and along the southeast Baltic coast. While traditional

thinking has seen them a farmers who migrated a lot, that idea is

not logical. Linguistically speaking, settled peoples diverge quickly

linguistically from lack of contact. It is impossible that they

would retain the same name in such diverse parts of Europe and over a

1000-2000 year time frame. Much more likely, the Veneti were a northern

equivalent to the Phoenician and Greek long distance traders of the

Mediterranean. The Veneti not only carried amber from the north to

Babylon, Greece and Rome, but also connected with brother colonies

across the northern seas. Once we begin seeing them as professional

long distance traders in the northern seas and up and down the major

rivers, we can apply truths about better known long distance trading

peoples such as the Phoenicians. Mainly long distance peoples

established markets along their routes and at terminals. That means if

archeology and ancient texts speak of amber coming down from the

Jutland Peninsula or southeast Baltic to the Adriatic Veneti, it is

valid to propose that the original Adriatic Veneti cities were

established from northern amber trader initiatives, and managed in the

northern language. When successful, these cities at the southern

terminus, drew surrounding peoples into it.

Although ancient trade was mostly by water – seas

and rivers were free highways never needing maintenance – because

of the barrier of the Alps, the Adriatic Veneti displayed plenty of

attention to the horse - a necessary animal for crossing the mountains.

Even if they could follow river valleys, while the rivers tumbled down

from the mountains they were often too rough for boats until they

reached the coastal plain. Because the use of the horse for

crossing mountain trails, as well as other uses, Venetic archeology

shows much reverence to the horse. Men involved in shipping might

become as attached to their horses or boatst. Accordingly a man's

journey into the afterlife might include either his horse or boat,

whichever applied to his profession

THE

ANCIENT VENETI LANGUAGE AND WRITING

A significant development among the Veneti was

the development of writing. Obviously influenced by the writing done by

the Etruscans to their south, the Veneti borrowed the Etruscan alphabet

and modified it to suit their language. Notably they added a couple

more letters and introduced a practice of placing dots before and after

some letters. Etruscans used dots, as did the later Romans, to mark the

boundaries of words. But the Veneti put dots throughout a word, and

that meant they used dots for another purpose. Scholars have speculated

on these dots. In my analysis of the inscriptions documented in THE

VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language

from a New Perspective: FINAL

found that they were markers for a phonetic writing that specified

linguistic features like palatalization with the dots. These dots

were used like a linguist today, transcribing speech phonetically,

might add marks to indicate length, breaks, and other features like

palatalization, except the Veneti dots were not too specific They were

all purpose markers, I found, that generally marked deviations from the

pure sound caused mostly by interference by the tongue. I discuss it in

great detail in THE

VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language

from a New Perspective: FINAL with examples.

But why use writing that described the sentences

phonetically? If the Veneti originated as long distance traders, I

think the phonetic writing approach developed from a need by traders of

being able to reproduce common phrases of foreigners encountered at

markets, even if one did not know the langauge –sentences like ‘this is

a good price.’ The word-boundary writing approach used by

Etruscans and later Romans, which is so familiar to us today (like

right here) requires prior knowledge of the language patterns.. Venetic

traders, thus, could create phrasebooks for all kinds of customer

languages, like Phoenicians did, and introduce dots to help in properly

reproducing it even if not understanding how the phrase was

constructed. If this is true, then there may be some instances of

Venetic writing containing another language, but we assume that most of

the Venetic inscriptions found in Northern Italy, reproduce the ancient

Venetic language dialect of the people there.

The Venetic language found in the inscriptions was

originally thought to have been a version of Etruscan. Then because

Greek historian Herotodus had mentioned “Ilyrian Eneti” (Ilyria was the

ancient region east of the Adriatic and north of Greece), the next

belief was that the Veneic language had been Ilyrian. Failing with that

theory, in the 1960's it was thought to have been an ancient Latin.

These hypotheses were all arbitrary guesses to be tested. Unlike the

Ilyrian theory that was limited by the lack of information about

Illyrian, plenty was known about Latin, and that promoted large numbers

of investigations, all seeking to decipher the inscriptions. Since

Latin was known, scholars loved to try to "hear" Latin-like sentences

in the Venetic inscriptions. The fact that some Venetic words

seemed close to Latin helped to solidify the belief Venetic was an

early Latin. The fact that it was only an arbitrary hypothesis where

failure was a legitimate option, was forgotten. Today tens of thousands

of academics fully believe that the Latin hypothesis is correct for no

other reason than it has been analyzed so much – as if the more words

are printed by scholars, the more correct

Since then there have been attempts to see if

Venetic was Celtic or Slavic. Some Slovenian scholars, inspired by

nationalistic pride, proceeded to try to find the Venetic inscriptions

were Slovenian-like. But none of the results of past deciphering of the

Venetic – whether via Latin, or Slavic, or anything else –

has been convincing. There is too much turning mystery segments into

meaningless proper names (ignoring the fact that ancient names were not

meaningless) There is also too much twisting words to fit each

other, or too much rewording poetically until some kind of non-absurd

meaning is reached. As far as grammar is concerned, either there is no

rationalization of grammar at all, or the grammar is assumed a priori

from the language used as a tool of interpretation, and not determined

from Venetic examples. And let us not forget the common practice of

scholarly papers showing only the handful of good results and hiding

the failures. (In THE

VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language

from a New Perspective: FINAL

I hide nothing. I list all the Venetic sentences used in the study and

at the end acknowledge them all, even if some results are incomplete or

with some degree of uncertainty.)

Furthermore, all the attempts to decipher the

Venetic inscriptions have not done any proper deciphering, but rather

proceeded by trying to hear a particular known language in the Venetic

sentences – a methodology I call the ‘hearing things’ approach.

This is a methodology that can begin with ANY known language, and hear

that language in the Venetic – an easy process if the portions that

remain mysterious are arbitrarily assumed to be proper names.(ignoring

the fact that in ancient times names too had descriptive meanings.) The

methodology can be easily described in two steps: a)decide the Venetic

inscriptions are related to known language X, b) try to hear words of

language X in the inscriptions when sounded out, c) turn all the

portions that do not sound like words in language X into meaningless

proper names. d) play around with the results to make it seem

meaningful and not absurd. This is a methodology that will be

able to produce the same kind of inadequate results no matter what

language X may be.

I give one example of a past deciphering from

the Latin perspective.

.e..i.k.go.l.tano.s.dotolo.u.dera.i.kane.i

Venetic, divided by analyst : eik goltanos doto louderai kanei

Latin (literal): hic Goltanus dedit Liberae Cani

English translation: Goltanus sacrificed this for the virgin

Kanis

Note that the literal Latin barely

resembles the original and requires the invention of two proper names Goltanus and Cani.

It is nothing more than a puzzle game that

gives a row of letters and instructs the player to ‘construct a

sentence in your language from this row of letters’. This is what I

call the ‘hearing your language in it’ methodology that is really

essentially the same as hearing sentences spoken by wind in trees. In

this case the game was one of finding Latin-like words in the Venetic,

and then turning the rest into proper names and then manipulating it

all to form a coherent concept.

It did not help the situation when some words seemed

close to Latin (such as dona.s.to

sounding like Latin donato

and or .e.go seeming like

Latin ego).

The more Venetic was pursued as an archaic Latin-like language, the

more academia became convinced it was true. More recently the same has

been true of Slovenian pursuit of Venetic as a Slavic language. Here

too it seems the more noise is made about it, the more the laypeople

and naïve academics begin to believe it is true.

This approach resulted in presumptions about some

word stems and case endings, which in turn invited linguists to apply

their wisdom to the presumptions. Looking at what the past Latin

approach produced regarding grammatical endings, I found little more

than a presumption about gender marking endings, and a dative. They

were the only grammatical features with enough evidence in the Venetic

to seem to confirm them. The rest of the proposed case endings were

based on only one or two presumed examples. As for the presumed word

stems, because of the liberal way in which mysterious segments were

turned into proper names, a third to a half of the word stems listed

were such meaningless names of deities and people. But is it valid to

simply assume untranslatable leftover pieces were proper names? Any

mother looking for a name for her baby and studying books of names,

knows that all popular names had meanings in their original

languages. Linguists, assuming the work was collected, leapt onto

the bandwagon with their own interpretations of linguistic shifts, etc.

But the reality is that this methodology would allow Venetic to be

‘proven’ any language on earth. For example a Chinese analyst could

also look for Chinese-sounding elements, and then turn the left-over

pieces into presumed proper names. And then the linguists would leap

forward to make linguistic pronouncements, with reference to Chinese.

(Anyone who disputes this, is welcome to test it themselves. Give some

Venetic sentences to a Chinese analyst and tell them it is an ancient

Chinese written in Etruscan letters, and prove it for yourself.)

The Ancient Veneti, by my theory, managed a long

distance trade network, of which the Adriatic, Brittany and Vistula

Venedi were three major nodes in the system. As long as the long

distance shippers/traders were in contact with one another, the

language remained relatively unchanged throughout the system. With the

rise of the Roman Empire, Romans established control over all economic

activities, and that included Romanizing the original trade systems.

The original trade systems were compromised. The major Venetic regions

– Brittany, southeast Baltic, and north Adriatic – were cut off from

one another, so that the regions became more localized. The north

Italic Veneti assimilated early into Latin when the Roman province of

Venetia was created. Later the Brittany Veneti assimilated into Celtic.

Finally the Venedi of the trade routes connecting the Baltic to both

Black Sea and Adriatic Sea assimilated into the Slavic peoples who were

their major customers. Before the original Veneti were completely

melted into their surroundings, there was a 1000 year period during

which historical texts could imply the Veneti in the three regions were

Latin, Celtic, or Slavic. There is some validity therefore in speaking

of Latin Veneti, Celtic Veneti, and Slavic Veneti for the 1000 years of

the post-Roman era, before the name itself disintegrated. But it is

incorrect to project post-Roman information to before the Roman Empire

as if the Roman Empire was an insignificant historical event, instead

of a complete transformation of Europe.

In the post Roman period, obviously the north Italic

Veneti became Romanized and today’s Veneto dialect arose from Veneti

assimilating into Latin. At the same time, obviously the Venetic

traders travelling from the Baltic, via the Oder or Vistula to the

Black or Adriatic Seas were now selling their wares to Slavs expanding

in every direction around the east side of the Black Sea and they

assimilated into Slavic. (It is interesting to note that the Roman

historian Tacitus, in Chapter 46 of his Germania, wrote that the

Vistula Venedi, by 98AD, were acquiring “Sarmatian” wives and

customs, and losing their original characterisitcs of the geographic

region of Germania. Since the Roman view of “Sarmatia” covered the

Slavic territories, he was in effect saying that the Venedi were

becoming Slavicized in his time (98 AD) It means the Venedi was

NOT Slavic before the Roman era.

In this article we distinguish the original ancient

Veneti from the post-Roman Latin, Slavic, Celtic etc Veneti, through

the term ‘Ancient Veneti”

As a result there is a war between the groups. Each group claims that

the Veneti were Latin, Slavic, Celtic, or some other alternative back

to the beginning of time (so to speak). Speaking in terms of another

long distance trading people – the Phoenicians – that would be like

discovering that the Phoenicians of Spain spoke Latin after the Roman

Empire, and then claiming they were Latin back to the beginning of

time. In that case, the Phoenician language is known from elsewhere in

the ancient world as a Semitic language.

In this war of Venetologists the arguments are based

distortions, trickery, reference to selected supportive ideas in

historical texts, geography, archeological discoveries, etc. But this

achieves no resolution. The truth about the pre-Roman ancient Venetic

language lies in a PROPER deciphering of Venetic inscriptions like

documented in THE

VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language

from a New Perspective: FINAL

2.

THE

VENETIC WRITING - THE OBJECTS

THE

ORIGINAL ANCIENT

LANGUAGE RECORDED IN THE VENETIC INSCRIPTIONS

We would today have no idea what the ancient Venetic language was like

if archeologists had not found inscriptions. What is the nature

of the objects archeology has been finding that serve as carriers of

the ancient writing and the language it reflects?

The first major archeological discovery in northern

Italy was made in 1876 at Este when two burial tombs were discovered

containing numerous cremations and bronze artifacts. In the next six

years, hundreds of such burial vaults were discovered and investigated.

These and subsequent investigations led to the rich world of

archeological finds of the Este area. Many of the archeological objects

had writing on them in an alphabet that resembled the Etruscan

alphabet. It was evident that before the rise of the Romans, the

Eneti/Veneti cities at the north end of the Adriatic Sea, borrowed

writing habits and alphabet from the Etruscans to their south and

adapted it to their own language. With it, they put their language onto

objects of ceramic, stone, and bronze (and no doubt many other

materials that have since decomposed) primarily during the period

between 500BC and 100BC when the Venetic cities were at their peak, and

ancient Greek historians described them as a wealthy civilization of

"50 cities" who were also the agents for northern amber being

distributed into Mediterranean markets.The objects on which they wrote

their inscriptions were objects with special uses in their religious

and regular lives. All sentences are short, and an addition to the

object and its purpose.

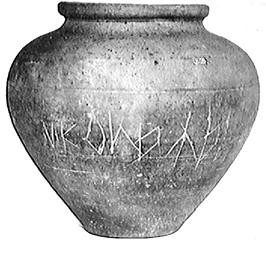

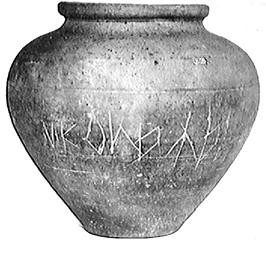

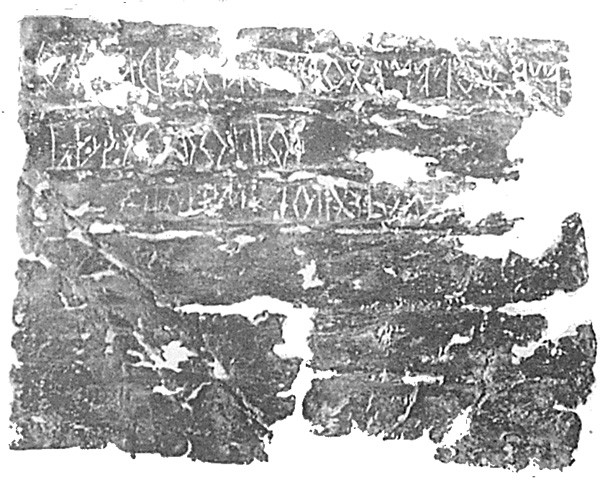

The Veneti made plenty of ceramic containers. The

techniques of making ceramics were varied and sophisticated. Much

pottery was decorated before or after firing. Some containers of

terracotta were used to conserve cereal grains and legumes, to cook

food, and of course table ceramics for eating and drinking. The form of

ceramics that was inscribed by writing was the cremation urn.

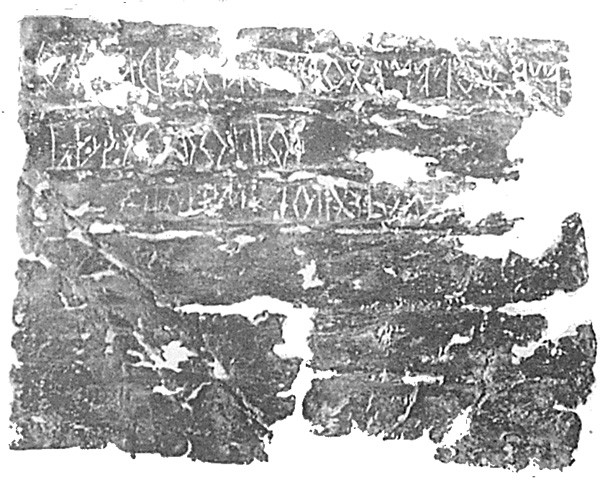

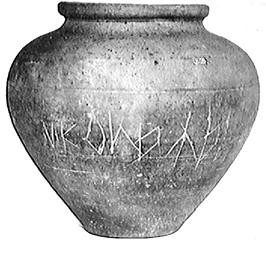

Example cremation urn inscribed with

writing

The cremation urns have provided the largest

quantity of examples or writing. They can be viewed as sendoff messages

to the cremated deceased inside. The (V)Eneti followed the

practice as spread in the “Urnfield Culture” (which can be associated

with (V)Eneti colonies elsewhere in the trade system of Europe), of

cremating their dead, placing their cremations in urns, and placing the

urns in tombs or in burial vaults. Along with the urns the tombs

contained valuables, perhaps that belonged to the deceased. In some,

goblets, plates, etc. were interred, perhaps from the funeral

banquet(?).

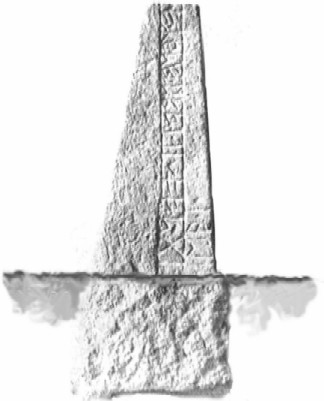

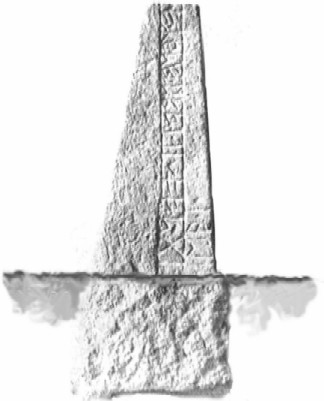

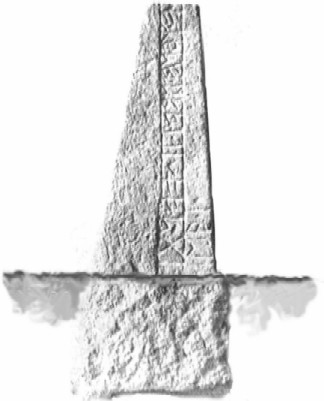

Outside the tombs, one might find stone obelisques

marking the locations of the tombs. The stone that stood upright, one

end rooted in the ground that typically had written on it a sentence

beginning in “.e.go….”

These texts have been interpreted traditionally, using the Latin

ego, which means ‘I’. It is not very believable that the deceased

said "I am -----", when throughout history tomb markers have been

dominated by the sentiment - rest in peace, or in memory. (I offer an

alternative below, that claims .e.go meant

'let remain, rest')

An example obelisque with its

inscription, that marked tomb locations

Also connected with tombs but perhaps it was a custom unique to the

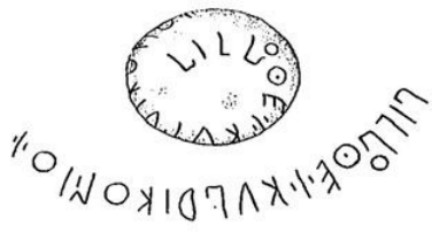

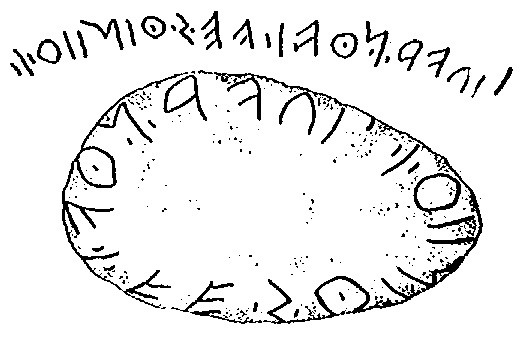

Pernumia area south of Padua, were a small number of round river stones

engraved with texts. They were left at the bottom of tombs and the

context of it suggests they were additional personal messages added

before the tomb was closed up.

Example round inscribed strone left at

bottoms of tombs at Pernumia

Getting away from funerary inscriptions (which are sad) we can look

now at sentences surrounding relief images on pedestals. These, we

found, look and sound like memorials, and perhaps some of the memorials

related to deceased, but many celebrated other notable events

–marriages, armies going off to war, distinguished visitors depart.

Example memorial stone, this is a later

one with Latin text which I believe announces a married couple setting

off on a honeymoon.

Another category of objects are objects left at sanctuaries,

religious places, where offerings were made to the Goddess. According

to ancient Latin and Greek authors, the sanctuaries in the north

Adriatic landscape included groves in a natural state often fenced in

to define their boundaries. Inside the sanctuaries space one would find

the facilities – including pillars, statues, pedestals, etc – for

practicing the religion whether it be processions, rituals, prayers,

burnt offerings. Permanent temple structures were only built in more

important sanctuaries in the larger cities. Religious rituals carried

out at the sanctuaries included purification rituals involving liquids,

and sacrifices of animals to deities. There were sanctuaries associated

with important urban places – marketplaces, ports, etc. There were

public sanctuaries associated with political and military centers

in a region. Communities too might establish sanctuaries in

association with natural features like springs. Ceremonies and rituals

were carried out at sanctuaries. It was something like an outdoor

church..

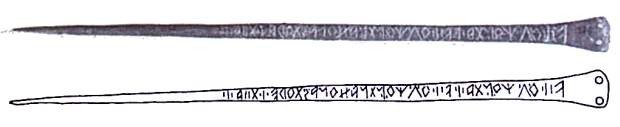

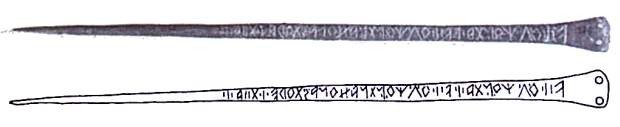

At the Baratella sanctuary near Este archeologists found large

numbers of bronze styluses. Most of these three sided writing

instruments had no writing on them, but some did. Why the accumulation

of them? Why did people leave them with their offerings - with or

without inscriptions? The answer is they must have used the stylus to

write a prayer at a shrine, on a thin soft sheet of bronze – a

few examples of which have been found. Once the prayer had been

written, the stylus was left behind, in a place of collection, perhaps

eventually to be recycled. Since it was only used at the sanctuary,

there was not reason for anyone to take it home.

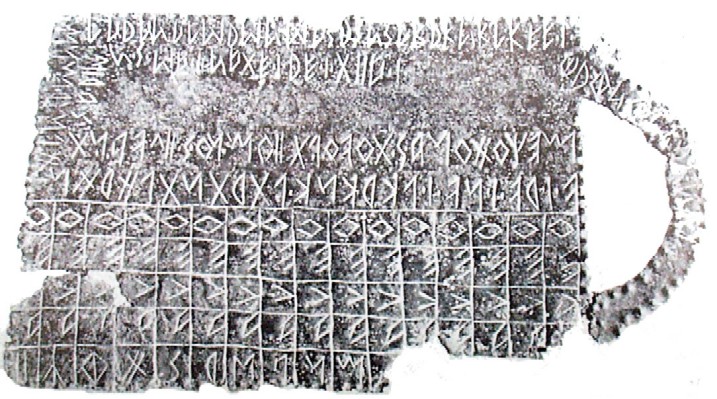

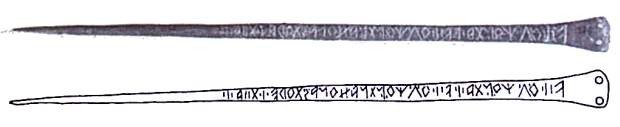

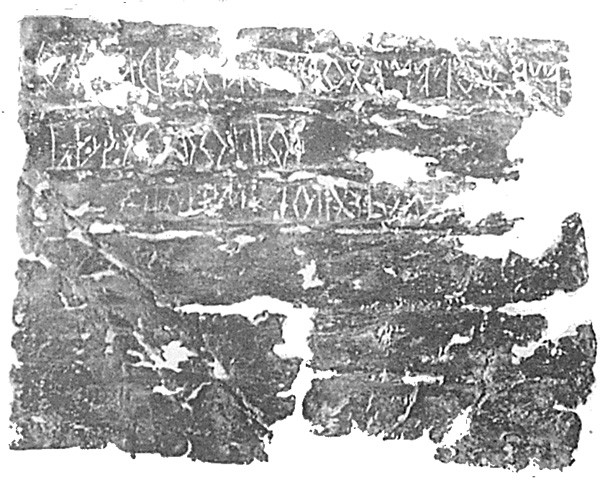

Example inscribed styluses used to inscribe messafes on thin bronze

sheets (below)

An example bronze sheet on which a message to the Goddess was

inscribed

The above categories - the urn, obelisque,

round stone, stylus and sheet - represent those categories for which we

have several examples of each - which allows us to employ comparative

analysis to affirm some repeated words and elements. There are

also some other groupings possible but the most interesting are the

inscriptions on miscellaneous objects – isolated finds, often of a very

common secular nature, which represents the everyday writing that

has been lost because it is not on durable objects nor accumulated in

large quantities anywhere. These randomly discovered objects

demonstrate the Veneti people used writing in very ordinary ways

as well. We can only imagine how extensively ordinary people may have

used writing on objects that did not last in the ground!

It is because ordinary writing does not accumulate

and was done on materials that decomposed, the body of discovered

(V)Eneti inscriptions as a whole are dominated by sentences found

on sanctuary and cemetery sentences. Accordingly past interpretations

have looked for solutions based on Roman patterns in later

cemetary or sanctuary inscriptions. This has led to the scholars

allowing most of the inscriptions to resemble what we might see today

on gravestones and memorials –a few keywords and names assumed

from untranslatable fragments. This allowed troublesome portions of

text to be viewed as proper names, and for the translations to be

non-sentences with assumed ideas.

Unfortunately, the number of examples of Venetic

writing is relatively small. Several hundred examples have been

found, but most are fragmentary, There are less than 100 good,

complete, inscriptions. When the number of full sentences is small, the

repetition of word stems, case endings, and patterns in style and

meaning is also small. It reduces the ability to confirm

suggestions about meanings or grammatical elements through internal

comparisons (between sentences containing the same word stems and

grammatical features).

The greatest shortcoming of the body of Venetic

inscriptions so far uncovered is that there are no examples of

inscriptions with an accompanying translation in a known ancient

language. Translations could at least establish with certainty the

words and grammar of that particular writing and then carry these

discoveries into other inscriptions. The successful translations of

ancient unknown texts have always had examples of writing with parallel

texts in a known ancient language. For example headway has been made

into Etruscan because of inscriptions with translations in a known

language like Phoenician.

Past successful deciphering of ancient writing has

benefited from at least a few translations in a known ancient

language like Greek. Having a few translations allows the analyst to

acquire a few solid, certain, words. Let us say that we determine

the meanings of two words of the unknown language to mean ‘man’ and

‘food’. We can then look for those two words in untranslated

examples of the unknown language. For example we find ‘man’

---?--- ‘food’ and we can infer that the ---?--- word could be ‘eats’.

We can now TENTATIVELY assume ---?--- means ‘eats’ and look for that

word elsewhere. Then when we manage to get partial translation in

that other location, we can see if the interpretation ‘eats’ fits. Back

and forth we test good possibilities for the unknowns between the

knowns we acquired from the parallel translation. This is exactly how a

baby learns language. One day the mother points to a dog and tells her

baby it is a ‘doggy’. The baby assumed that is the word for

a four legged creature. But then on another day the baby points to a

cat and says “doggy”. The mother replies “No, that is a kitty”.

Language learning is all about making hypotheses and testing them until

one arrives at a system that works – the final meaning of the word is

the one that works correctly everywhere it is used.

This example suggests that there is another way of

determining meaning – from context. When the baby points to a dog

or a cat when saying “doggy” or “kitty”, she is captioning a real

object. In the case of ancient inscriptions, it helps if there are

pictures associated with the text. The writing has to be captioning the

pictures. Furthermore there are labels. If we buy a refrigerated carton

in a foreign country that shows the image of a glass of milk, we can

assume that the word for ‘milk’ will be prominent in the writing on

that carton.

3.

THE

MYSTERY AND THEORIES ABOUT THE ANCIENT VENETIC LANGUAGE

THE

ARBITRARINESS OF PAST IDEAS ABOUT VENETIC

Without archeology ever finding translations

of Venetic in a known ancient language, the investigation of the

meanings in the Venetic inscriptions has been quite blind. They have

had to advance theories based on periferal or indirect evidence.

Ancient history only tells us (Polybius) that

although allied with Romans in wars against Celts, and employing

customs in Gaul, they spoke "their own language". This at least

should tell us Venetic was not close enough to Latin or Celtic or any

other well known language of the time to be seen as a dialect of it.

The first scholarly proposal some centuries ago was

that it was a northern Etruscan. It was suggested purely from their use

of the Etruscan alphabet. The next proposal that it was an "Illyrian"

language (Illyria was the ancient region east of the Adriatic and north

of Greece) was based on the ancient Greek historian Herodotus

mentioning an Ilyrian "Eneti". These early proposals failed to be

fruitful and in the end someone said why can't we assume it was

ancestral to Latin? It was a guess, based only on the fact that Venetic

was located in the Italic Peninsula like Latin, and because the

Venetic inscriptions provided a few words that looked remarkably like

Latin - for example dona.s.to

and .e.go closely resembled

Latin donato and ego.

This final theory in the academic world produced a great amount of

scholarly analysis for the simple reason that Latin is well known and

anyone who knew Latin could try to see if they could hear Latin

sentences within Venetic inscriptions. The results however are

very poor by scientific standards - often being little better than

hearing sentences in the sounds of the wind through the trees. Then

scholars, finding the results a real mess, tried to bring some

linguistic integrity into the accumulated Latin-oriented study, now

only assuming only that Venetic was an ancient Indo-European that need

not be ancestral to Latin but maybe related. That is how the pursuit

stands. But the results were still not convincing. The fact that by the

1980’s some Slovenian academics took on the Venetic inscriptions

with Slovenian and Slavic proves previous work was not convincing

enough to discourage new theories. But the Slovenian approach too

simply tried to hear Slovenian-like sentences in the inscriptions.

There has been no rationalization of word stems or grammatical elements

– just a lot of trying to ‘hear’ Slovenian-like sentences in the

Venetic when sounded out, followed by plenty of massaging and poetic

twisting to arrive at meanings that do not sound absurd.

In the absense of any way to determine the meaning

of any words through a parallel translation in a known language, the

entire history of analysis of the Venetic inscriptions has been like

blind scholars wandering this way and that with arm’s stretched out,

and making guesses about what they are feeling and where they are going.

If you have committed to one hypothesis, will you

admit defeat and stop? No. Who can admit they have spent years of their

lives achieving nothing? Let us not forget that the proposals that

Venetic was Latin-like, Slavic-like, etc have only been UNPROVEN

HYPOTHESES, and that all they are doing is testing the unproven

hypothesis. Then, over time the academic world forgets that the

linguistic nature of Venetic had simply been arbitrarily advanced for

testing, and after thousands of man-hours have been spent, everyone has

completely forgotten that the notion that Venetic was Indo-European in

a Latin-like way or in a Slavic way, as the case may be, has always

been an arbitrary hypothesis advance for testing, and that if

the testing has not produced convincing results, the option that the

hypothesis was incorrect is a valid conclusion and that it is not

necessary to keep forcing the hypothesis onto the Venetic.

This is different from having a priori

proof before attempting the deciphering. For example, if the Venetic

inscriptions were FIRST proven to be an archaic cousin to Latin, then

the pursuit with Latin would be valid. For example if Polybius had said

"Eneti spoke their own dialect of Latin" then that would form a

non-arbitrary foundation for the pursuit.

But if the Latin hypothesis were forced onto Venetic

for no reason to test yet another hypothesis, then everything that

follows is a testing of the hypothesis and one of the valid results is

that the hypothesis is false. But this is forgotten, and the analysts

now have assumed it to be true and will not admit that they may have in

reality disproven the hypothesis from general failure.

If modern scholars do not realize they are ONLY

exploring a hypothesis they will tend to regard poor results as their

own failures in analysis, and not as a failure of the initial

hypothesis.. But there has always been the option that the hypothesis

was wrong and the failures in achieving the believable and convincing

results are the consequence of all the hypotheses being incorrect.

The entire methodology followed in the past half

century has been wrong. Instead of guessing the linguistic nature

arbitrarily and then spending years of frustration on an erroneous

path, why not pursue the determination of the correct hypothesis first,

before investing a great time and effort testing with a known language?

Too little academic energy has been spent trying to find evidence that

eliminates the guesswork. Instead of a history of blind men walking

around in the dark and making guesses, Is it possible to prove a

hypothesis of linguistic affiliation a priori before beginning to try

to force Latin (or Slavic) into the inscriptions based on vague

similarities in sound? Certainly it would be possible if we had a

parallel translation. But is that the only way?

A

FURTHER OPTION OF VENETI ORIGINS: TOWARDS THE NORTH

The problem with making an a priori hypothesis and

then getting stuck with it because nobody wishes to admit failure, is

that the hypothesis becomes entrenched and nobody then considers any

alternatives. All the alternative options, such as Venetic having

come from the north via amber traders, are shut down, and the entire

quest for discovering Venetic truths comes to a dead end. Let us

consider other options that the narrow stance of the past has thwarted.

For example, there has always been a valid

possibility that Venetic was NON-Indo-European, especially since Venetic had two acknowledged

NON-Indo-European languages as neighbours

- Etruscan and Ligurian. Indeed Etruscans were close neighbours and the

Veneti adopted the Etruscan alphabet. Why has it not been pursued? The

explanation is too simple: everyone knows Latin, but nobody knows

NON-Indo-European languages. It was an academic path of least

resistance!

Furthermore, the pursuit fell into the rut of being

focussed mostly on the sentences themselves, and little serious

analysis has been given to the archeological objects and contexts in

which the sentences have been found. But the more information you can

look at the better. As any crime scene investigator will attest, the

more information you collect, the clearer the truth becomes. Consider

what analysis of the archeological side of things can reveal.

Archeology can tell us if the object was connected to a funerary

ritual, acted as a memorial, marked a tomb, etc. Then we have a sense a priori

what messages would be most probable for that object and context. It

gives us a basis for accepting some possibilities and rejecting others.

Then there is archeological discoveries about the

world in general. For example if we see that the Veneti were intimately

involved in the Greek dominated Mediterranean, then the probability is

very high that the Veneti would worship the well established deity

Rhea, and not invent their own called “Reitia”. What else can we

infer from archeology on the larger scale? In the past century of

archeology, it has been discovered that amber came down to the north

Italic region from two sources in the Baltic, the Jutland

Peninsula and the southeast Baltic coast. Therefore we can

entertain the possibility that a northern language was transferred

south through this path of contact. In other words we cannot restrict

our attention to the Mediterranean. According to archeological

discoveries, the north Italic region where most of the Venetic writing

has been found was at the bottom of the amber trade route from the

Jutland Peninsula. From these origins, archeology has discovered from

amber dropped along the route, that amber goods travelled up the Elbe

River, crossed the Danube Valley to the Innsbruck area and then

descended the Adige River valley to the Venetic colonies at the bottom

of the Adige. This opens the possibility that the Venetic

language in the inscriptions came from the Jutland Peninsula,

established as a new southern terminus for amber trade.

Scholars have not excluded this possibility as they

have wondered if Venetic was Germanic, and while they found some

features that seemed Germanic, the conclusion was that it was not

Germanic. The Germanic hypothesis has not been pursued. That means

since the Venetic inscriptions were made before the Roman era, we

should be dealing with the unknown language that was found in the

Jutland Peninsula before the Germanic (Goth) militaristic expansions

northward from central Germany. And to identify that unknown

language, we cannot simply look at historical languages, but recognize

the aboriginal foundations of northern Europe, which were Finnic (like

the Saami, Finns, Karelians, Estonians, Livonians, and many other

remnants across northern Europe as far as the Urals.)

Archeology has found that the aboriginal peoples of

northern Europe began as reindeer hunters, but then became general

hunters of a flooded wilderness as the reindeer tundra

disappeared. The new culture, called the “Maglemose" culture,

spread across the north as far east as the Ural mountains with dugout

boats, and then invented skin boats (skin-on-frame construction) in the

arctic where there were no trees for dugouts. While linguists can

argue over fine points, looking at the broad picture, the aboriginal

peoples of northern Europe were boat peoples, and as such could easily

adapt to farmer civilization by performing the role of long distance

traders. With such boat-oriented roots, descendants of the aboriginal,

indigenous, north Europeans, were preadapted to enter into roles in

long distance shipping/trading, and for that reason we have to find

that the most likely large scale trade language across the northern

seas remained Finnic. in character even as intermarriage with the

farming peoples altered the original peoples in the caucasian direction.

It is well known that in the Mediterranean, the

Phoenicians established trading colonies everywhere they went, and set

up trade networks. Greek traders did the same. This was a standard

practice of long-distance traders.

What if, derived from the northern trader tribes, amber

traders of the Jutland Peninsula established the trade route to the

Adriatic, and that formed an ongoing relationship via trade, or they

may even have established the colonies at the south end of the route

and planted colonies of their own people there. That was what we know

other long distance trader peoples did. Ancient Greece was

a major customer for amber, dating to over 2000 BC. The original

colonies at the lower Adige River could have initially been established

as trade centers for handling goods coming from the north, and goods

heading onward into the Mediterranean markets. Once established and

successful the Venetic cities would have drawn surrounding peoples into

their midst, but preserved the northern language as the general

language of the region.

Such an investigation of archeological knowledge on

a larger scale raises the possibility the Venetic inscriptions

CAN have a high probability of being Finnic in character. The

wider our net for information gathering, the more we open our mind to

possibilities not thought of previously. If indeed the Veneti were long

distance traders, we cannot look at the Venetic inscriptions purely as

a local phenomenon.

We cannot isolate the Venetic inscriptions from the

ENTIRE context in which they occur – not just the local context of a

funerary site, etc, but the larger context suggested by the name

appearing through ancient history in Babylon, the coasts of the Black

Sea, Illyria, southeast Baltic, Vistula, Oder, northwest Europe,

Adriatic Sea, etc….Once we decide they were long distance traders based

in the north and dominating major rivers, we begin to view the Venetic

inscriptions in a new way.

Our first step is to ignore that actual Venetic

sentences, and study the entire archeological context for what is

possible and then evaluate all the possibilities for what is

PROBABLE. Then we will have a good intuitive sense of what the

sentences will say, and at least we will have a sense of what is

absurd, what is possible and what is both possible and most probable.

By always selecting what is most probable, we gravitate towards the

truth. We can then determine when we are proceeding towards the truth,

by finding our discovery of the language accelerating like always

happens in correct language learning.

It is only then that we begin to note that the

resulting language that we discover has similarities to one known

language or another. If we then employ that knowledge as an additional

tool, we are no longer forcing something onto Venetic, but employing a

correct tool for further revealing the truth.

4.

SEARCHING

FOR THE PROPER

METHODOLOGIES OF DECIPHERING ANCIENT INSCRIPTIONS

THE

PROPER WAY TO

DECIPHER THE VENETIC INSCRIPTIONS

The practice employed with the Venetic inscriptions of simply making a

hypothesis of affiliation with a known language and then trying to hear

that known language in the inscriptions mentioned above, has not the

normal approach in deciphering ancient inscriptions.

Past successful deciphering of inscriptions has been

approached from an archeological direction, where every piece of

information connected with the writing is brought into the deductive

process. Unlike a linguist, who views sentences in isolation, an

archeologist sees the inscription wholistically in the archeological

context, and then the writing is treaded like elements of the

archeological whole, and the task becomes an extension of interpreting

the archeological information.

Linguistics looks only at the sentences, and a great

amount of information that can reveal meaning in the inscriptions is

lost. For that reason an unknown language cannot be deciphered by

linguistics. Meaning is found in the context in which a language is

used and that means we must observe the language in its real world

context. A linguist trying to understand an unknown language

being spoken by a newly discovered people, can only determine meanings

from observing it in use. A baby too needs context from which to infer

meaning. We cannot separate language, whether spoke or written, from

the real-world context in which it occurs. Iif we went to a foreign

country today and found a jar with a word on it, and there were beans

inside, we can determine that the word means 'beans', whereas when that

word is separated from this context, it cannot be deciphered.

Linguistics needs a correct understanding of the relationship of an

unknown language to a known one to proceed without any reference to the

realworld context. But if the relationship is unknown, then linguistics

is blind. Archeology is not, since archeology has the realworld context

to investigate.

But the amount that can be discovered from a

wholistic archeological perspective varies with the situation. As I

mentioned earlier, if there is an archeological find that shows a

translation in a known language beside the unknown language, then there

is less need for inferring meaning. It would be like a student of a

language looking up a word in a dictionary, rather than making and

testing guesses. Unfortunately archeologists have never found a Venetic

inscription that is accompanied by a parallel text in a known ancient

language, and it has never been possible to determine a few words with

certainty. Scholars may believe that translating words like dona.s.to and .e.go

with Latin donato and ego ; but these may be coincidences since human

languages use the same limited number of vocal sounds. All languages

will have words that are similar in sound to words in any another

language. We cannot go by a few similarities. The similar

sounding word in one language can mean something completely different

to a similar sounding word in another language. For example the first

of these, dona.s.to, resembles

Estonian toonustus 'something

brought' and the second, .e.go

, resembles jäägu

'let remain'. And then we can investigate other languages and

find similarities there too. Even English – which did not exist back

then – can give us donate and

ego

We can imagine the absurd sentence we would get from that. Thus mere

coincidence with a known language proves nothing. It is not

enough to find dona.s.to and .e.go is similar sounding

to Latin donato and ego. Proof is needed that these

similarities are valid, and not the similarities in another language.

If we lack any discovery of a parallel text in a

known language, we can still learn a great deal about the language by

the traditional direct methods described above that approach the

inscriptions from an archeological point of view. If we can find some

words in this way that can be viewed as certain, we can then have the

handful of solid words we can then use to leverage more words, just as

well as if we had found a parallel text.. Since the Venetic texts are

written on objects with a clear purpose and context, Venetic has always

been a very good candidate for looking for highly probable meanings in

this way. But until I tried it, I don’t think it had been tried before.

I have already described how a visitor to a foreign

country might learn some words of the unknown language from the way

they are used. For example the word in a sign above a bin of apples

probably says 'apples', or the large word on a carton of milk, probably

means 'milk'. A red stop sign at the end of a street probably has a

word that means 'stop'. By searching all the objects that have

inscriptions on them, we can find some

for which the objects and their use suggests highly probable meanings

of some words in the inscriptions. We only need to find a handful of

words whose meaning is obvious, which also appear elsewhere, to

leverage meanings in still-unknown words in other sentences. For

example, if we have one word that also appears on another object in a

two-word sentence, we can use the context of the other object and the

meaning of the one word to make a very good guess for the meaning

of the second word. The proposed meaning of the second word can then be

tested on yet other inscriptions. Soon we will find four word sentences

in which three words are known and we can infer the fourth. The process

accelerates. Every new discovery leads to even more discoveries, so

that if we observe the deciphering becoming increasingly easier, we

know we are on the right track. If we get stuck, then we can conclude

that we made a mistake earlier and we can backtrack and try another

alternative.

This is the traditional methodology of interpreting

ancient unknown inscriptions directly. A handful of correctly

deciphered words can be leveraged to decipher a hundred words, . This

methodology, when it produces correct results, accelerates, just like

when a child learns its parents' language, its learning accelerates -

from a very slow start, the child is speaking well by the age of

three. The same should occur in deciphering ancient writing - as

long as the analysis is correct, the analysis accelerates. It is a way

to sense it is on the right pa th. If the analysis gets stuck,

the analyst has to backtrack and look for the error

This acceleration is counter-intuitive since in

ordinary learning, the more one learns the more challenging further

learning becomes. But language is not a body of knowledge, but a

system. In any learning about using a system., the more you know, the

faster you learn more. For example learning to play a musical

instrument is learning the system of making music. The beginnings are

slow, but then the learning accelerates. The fact that analysts have

fussed over Venetic for centuries should be proof that the analysts

have been on the wrong track. Any belief that deciphering Venetic

should be a struggle of many centuries is completely false. A correct

deciphering can begin very slowly but like a child learning its first

language, to be on the correct path it should accelerate - that is take

several months and not several decades or even centuries.

The methodology presented below resulted in the

deciphering of most of the known inscriptions within two years

(2002-2004) with the discoveries constantly accelerating. This

parallels how a child learns its first language. We learn

Venetic by starting with the simplest sentences.

EXAMPLE

OF

IDENTIFYING A VENETIC WORD FROM INTERPRETING THE CONTEXT

When dealing with the written language children's books are filled with

illustrations that describe what the words are saying. Comic

strips and cartoons too provide visual information to help interpret

the texts.

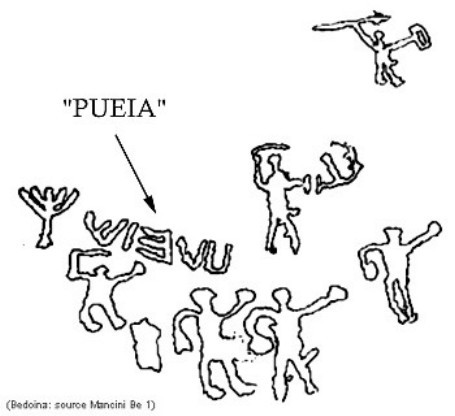

There is one Venetic inscription that is like a

cartoon. The figure below represents an isolated find on a rock face in

a mountainous area (Bedoina) in north central Italy. The image shows

five men with fists raised shouting “pueia” while a man in the distance

seems to be running away. The treelike symbol with the five branches in

my opinion says five foreground men shouted it in unison. It is

analogous to a balloon in a comic strip.

Carved onto a rock in the mountains,

this illustration tells a whole story and limits the the possibilities

for the word that they are all shouting. It is like a cartoon with a

word balloon.

ANALYSIS:

It is important to note that the foreground men have their fists

raised. This suggests anger. But three of them have no weapons.

Therefore they are not a group of warriors heading after someone

and saying possibly “charge!” or something. We study the picture. Use

some shrewd analysis. It seems the fleeing man has upset the three

closed-fisted men. But the remaining to foreground men do have swords

and seem to be after the fleeing men. It seems to me that they are

shouting “After him!” or “Catch him!”. If these the foreground men had

no swords, and only fists, then we can propose they were just shoutiing

“Get out of here!” or “Go away!”. Thus the image as it is, seems like a

community set some armed men, maybe policemen of a town, to chase after

an escaping enemy or criminal. It would be consistent with chasing him

into the mountains. Reaching the mountains, maybe the fleeing man

escaping, they camp for the night and create this picture to record the

event.

Thus after analyzing the possibilities, the

most probable choice is that pueia

means ‘catch him!’m ‘stop him!’ or similar.

Tentatively assuming pueia means ‘Catch him!’, the next

step in the methodology, is to look for this word pueia in

another inscription and hope the context of the object and other words

support this same meaning. But this word does not occur elsewhere, and

in this case we are unable to use this word to leverage more words in

other sentences,

We can accept that pueia means ‘Catch him!’ and that would be a good

example of deriving a meaning without any reference at all to any known

language.

But should we ignore known languages? No. If we

allow the Venetic to search known languages for words that are similar

in sound and mean something similar to ‘Catch him!’ then we are not

forcing any known language onto Venetic, but allowing Venetic to scan

known languages for the best fitting word in any candidate language.

What is nice about this is that since Venetic does the searching, it

doesn’t matter too much that the languages scanned are modern ones,

since the Venetic will only see the remnants of actual ancient words in

that modern language.

Nearly all languages will have something sounding

similar to pueia,

but only one may have a meaning close to the desired meaning ‘Catch

him!’. The reader can scan known languages to find a word that fits the

meaning we arrived at from the picture. But ultimately the reader will

find the closest known word is in Estonian (a Finnic language) and its

word püija! 'catch (him, her, it )' Other languages may have

similar words with meanings that could be poetically manipulated to be

possible, but we are not interested in what is possible, but what is

MOST PROBABLE that ordinary humans would shout in the situation

depicted.

At least in this methodology we are not simply

matching sound, but also matching the meaning implied in the

information in the archeological context . This greatly reduces

the chance of false paths of analysis. In this way, it is the Venetic

that is projecting into its best known language, and not vice versa. In

general, as in a court of law, the more evidence there is pointing to

the same conclusion, the less the chance that our conclusion is just

opinion or wishful thinking.

As I said above, we could omit scanning known

languages completely and that would be ideal. However if eventually the

revelations from the direct approach keep pointing to Venetic being

Finnic in nature, then how can we not extend our methodology to use

Finnic language (Estonian or Finnish) as an addition tool to confirm

the meanings found directly, or even to suggest possibilities. The

truth is that had I not eventually begun using Estonian as an

additional tool, my results would have been more vague. The main

benefit when I began checking words with Estonian was to CONFIRM or

REFINE meanings. For example discovering Estonian püija!

'catch (him, her, it )' helped to settle on ‘Catch him!’ instead of

‘Stop him!’. It means they are trying to capture the fleeing man,

and not simply stop him.

EXAMPLE OF IDENTIFYING A VENETIC

WORD FROM INTERPRETING THE CONTEXT: GIVING A DUCK TO AN ELDER

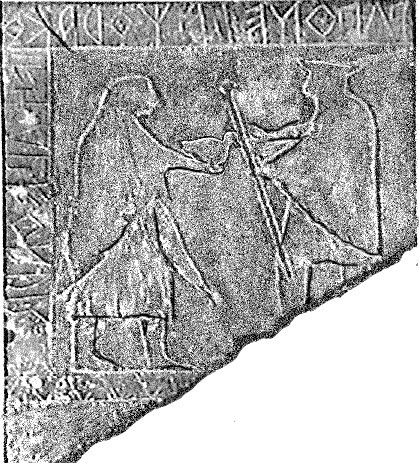

The next example is a better one, as it produces discoveries that can

now be applied more widely since it contains words found often in other

inscriptions - it permits internal comparative analysis between all

sentences in which a word is repeated..

1. THE CONTEXT.

This example is one of the inscriptions on the pedestals with relief

images. I believe they were intended as memorials of events, and did

not necessarily refer to someone passing on. For example there is

one in which we see chariots and our interpretation suggests

commemoration of the departure of an army into the mountains the engage

in a war. The example we will decipher appears to commemorate an event

where an important religious or political elder pays a visit, and upon

leaving is given a duck for the journey. It is a lovely example to

interpret directly because it gives a unique illustration depicting

what appears to be a peasant, maybe a fisherman or hunter, handing a

duck - probably a real duck - to a distinguished-looking man with a

cane. And the sentence obviously captions what we see in the image!

This image tells a story that will

reflect what is stated in the surrounding text. What does the duck

represent? It is possible that water birds were sacred to the Veneti.

See the earlier image on the disc, which shows a bird, possibly a swan

on the other side. Or was the duck given as something to eat on the

journey.

1. THE

INSCRIPTION:

The Venetic inscription is written continuously, in the fashion of

Venetic inscriptions and when the text is converted from the Venetic

alphabet to Roman small case alphabet, and including the dots in the

Venetic text, it reads - when the Venetic alphabet is converted to

small case Roman alphabet but preserving the dots:

pupone.i.e.gorako.i.e.kupetaris

(Notes: Reading the

dots. The dots in the

conversions of the originall Venetic writing to small case Roman

alphabet represent palatalizations of the sounds on either side of a

letter, and other features like trilled r, or aspiration. It

mostly affects how the language sounded, and it doesn't greatly affect

our discussion. For example .e.go only means it sounded more like "YHE-EGO"

instead of a pure "E-EGO" For detailed discussion of the dot

puncctuations see THE

VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language

from a New Perspective: FINAL)

3.

IDENTIFYING WORD BOUNDARIES:

For interpreting we need to break it apart into words. We can divide it

easily from identifying some of the words in other inscriptions. In

this case, the identifiable word .e.go

occurs in the middle, and .e.cupetari.s.

which is a word from how it is used in other sentences, at the end.

Thus the word boundaries for the remaining two unknown words are

obvious. The sentence with the word boundaries shown as spaces is:

pupone.i

.e.go rako.i. .e.kupetaris

4.

INTERPRETING THE CONTEXT:

Looking at the illustration we can propose that the text describes how

a peasant is giving a duck to a distinguished-looking gentleman as

suggested by his clothing and cane. We can expect that the words ought

to at least identify the central object, the duck. The first word

appears to have the stem pupo-.

We can determine this because the remainder -ne.i. appears as an ending in many

other sentences and is therefore a grammatical ending. pupo

sounds remarkably like universal words naming 'father'. It is the word

from which PAPA comes, and more importantly it is in the tradition of

the Italic Peninsula in being used to name the Pope. I believe

this was how in all the Italic Peninsula it was common to call a

leader, a city or county elder, as a ‘Father’ even before Christian and

Roman times. In conclusion we can propose that pupone.i.

may mean 'to the distinguished father' and that suggests that the word

for 'duck' will also appear in the sentence. Further deciphering

will conclude that the best meaning for ne.i. is similar to the

Estonian –ni, (Terminative

case) which means ‘(physically) up to the location of’. The duck is

extended physically as far as the Pupo. It is not a Dative, as the

Dative will imply the Pupo revieved the gift in more than physical

terms.,

5. INTERNAL COMPARISONS ACROSS ALL THE INSCRIPTIONS:

We have already noted how internal comparisons in the body of

inscriptions established that ne.i.

was an ending, and all of .e.kupetaris

was a word. The word .e.kupetaris

occurs repeatedly at the end of sentences that accompany illustrations

showing horses. The stem .e.ku

resembles Latin equus

for 'horse' and that has inspired previous analysts especially from the

Latin direction assuming the word referred to horses. But let us

analyze it properly.

Scanning the other inscriptions, we find that .e.kupetari.s.

occurs almost always at the end of a sentence. Most other sentences

with the word show people being transported by horses, which tends to

reinforce the notion that the Latin equus

is involved. But it does not work in this case, as one does not

give an elder a duck, using horses. There are no horses in the picture.

We need to compare the possibile meanings in all places the word

appears to determine what meaning fits

all instances.

Because .e.kupetari.s.

almost always is tagged to the end, we can propose that it actually

means something like 'happy journey' - a 'farewell' term - and that

since in ancient times journeys involved horses, we do not even need to

find Latin equus in the word.

For example .e.ku could be

the same as .e.go, occurring

with harder sounds for phonetic reasons (like consonant harmony) In

conclusion the fact is that .e.kupetari.s.

is an end-tag and is most probably a 'goodbye' or 'farewell' term. We

can propose that the duck is being given to the distinguished father as

a farewell gift.

We have already mentioned how .e.go always appears at the

beginning of obelisques marking tombs. Traditionally, assuming it is

the same as Latin ego

'I' those tomb markings have been interpreted as ‘I am [NAME]’ which

does not sound believable. It is human nature that the most

likely repeated word on tomb markers would be something like ‘here

lies’ or ‘rest in peace’, etc. Thus a natural way to interpret .e.go is with 'let rest, remain' .

This also suggests that the Latin approach could have obtained a more

appropriate path with Latin iaco,

which appears in post Roman gravestones in HIC IACIT 'here lies,

rests'. But the word that best fits is Finnic jäägu

'let remain, be' . Since iaco occurs alone in Latin vocabulary, it is

possible this is a word borrowed into Latin from Venetic, and not

genuinely Latin. In interpreting the .e.go

in the inscription with a duck being given to an elder, the problem is

that while on the tomb-markers the idea of 'rest-in-peace' etc

works, here I don’t think there is a tomb, and there is simply a

commemoration of a visit by a distinguished man. We have to revise the meaning of .e.go so that it is not specific to a

cemetary situation. Furthermore the meaning must fit the image.

One solution analogous to in English saying 'l LEAVE

the duck with the Father'.. Let's leave the duck with the

Father...Let's leave the deceased to the afterlife....Let the duck be,

remain, with the Father....:Let the duck rest with the Father.... Let

the deceased rest, remain, be, endure in the afterlife.

Our methodology thus tries to find the meaning that

fits all locations it appears. In conclusion:In that light the

inscription so far, from direct interpretation of the context and

cross-checking across all inscriptions is:

'To

the Elder, let

remain a duck. Happy journey!'

The only word left to analyze is rako.i.

We determine the ending (vowel).i. is a case ending because it occurs

often in the body of inscriptions. We eventually develop a quite

convincing belief that the ending is a partitive.

Thus the stem is rako

and

it means ‘duck’. But we do not know for sure - it could mean, for

example. 'present, gift'. We can leave the translation with this

uncertainty, or we can search for more evidence.

Here is where we can now look towards known

languages. We can allow our a priori establishing the sound of the word

and its probable meaning as ‘duck’ to scan known languages for

something that is like ‘duck’ and also sounds like rako. For

example, English has drake.

Can we explore where English obtained that word? It could be a loanword

from Germanic? Scanning candidate languages (languages with which

Veneti had contract), is not necessary in this methodology, but it does

not hurt, since it is the Venetic that is selecting from known

language, and we are not forcing something onto Venetic. Let us see if

we can find confirmation that rako

means ‘duck’ and not ‘gift’

6. SCANNING

KNOWN LANGUAGES WITH WHICH VENETIC HAD CONTACT:

We already have a strong probability that rako meant 'duck' and that

may be enough for a translation. But it is always interesting to scan

known languages in case we can find confirmation.

If we scan Latin, we do not find anything sounding

similar to rako that would fit. (For example Latin draco means 'snake') Anyone who

knows English will see some similarity to the English word drake

but we should trace the word to its earlier origins, since Venetic

predates English. We can look for it in other Germanic languages. Then

it would be a word borrowed into Venetic. We could also investigate

what is known about Etruscan. It does not help to scan Estonian or

Finnish because in modern Estonian the word for 'duck' is part and in Finnish anka.

But we can also recognize that there could be

remnants of rako

right there in the same place in the north Adriatic. When the ancient

Veneti assimilated in the post-Roman era into Latin towards the west,

and Slavic towards the east they would have preserved some words and

expressions, not to mention unique accents, from their original

Venetic. It is possible that the Veneto dialect of Italian, or the

Slovenian dialect of Slavic, contain remnants of Venetic. With this in

mind, I decided to access a Slovenian dictionary. I found that in

Slovenian 'duck' is expressed by the word raca.

Exactly what I was looking for! Proof that this word was a

remnant of Venetic within Slovenian can be deduced from the fact that I

did not find raca for ‘duck’

in other Slavic languages. It could be true that Slovenian men are

descended from Veneti, but the original Veneti assimilated into Slavic,

and it would be wrong to pretend assimilation did not occur, when

assimilation was so common since the Roman era.

We can of course continue to scan known languages

for the other words too to help confirm the results. If we were to scan

Finnic, we could as I have already said, find .e.go resonating with Estonian jäägu 'let remain, continue, rest'

which works well. The Finnic word jäägu

is one of the most common Estonian words. Words in constant use

generation after generation can be thousands of years old.

Furthermore, even though we can scan Latin and find equus for 'horse' to suit the .e.ku in .e.kupetari.s. but there is

nothing in Latin that is both similar to petari.s. and from which we can

form a word of the desired meaning - which we concluded was an end-tag

like a farewell.

But if we consider .e.kupetari.s.

as an end-tag we can also expect it can be abbreviated, in the way

English good-bye comes from a longer expression and is now progressing

to simply 'bye. A Finnic approach then can propose a parallel in jäägu pida reisi! 'let

it be (so-be-it), engage the journey. The use of jäägu nii

is still common in Estonian vernacular as in 'let it be so' 'so-be-it'

'okay then'. 'let it remain thus'. This proposes that the Venetic

expression began with .e.go

peta ri.s. and contracted from frequent use to .e.kupetari.s. Indeed further

abbreviating can even be found in some inscriptions, where the word

appears for example as .e.petars

If this is the case then the similarity to Latin equus is pure

coincidence.

7. PROBABLISTIC

CONCLUSIONS.

A methodology that, like archeology (or like crime scene

investigation), looks at ALL evidence touching upon the truth we are

seeking, works best if there is plenty of such evidence: the object

purpose is clear, the context is clear, there are many sentences in the

same context, and many words and grammatical elements are repeated to

allow cross-checking of results for linguistic consistency. But in

practice, the amount of evidence varies. Results achieved from direct

analysis of context, repetitions throughout the inscriptions,

grammatical structure, etc are only as good as the amount of evidence

we find and analyze. This evidence includes known languages with which

Venetic could have had strong contact, as all languages borrow words

from other languages, and the other languages from Venetic. (For

example, earlier I proposed that Latin

iaco actually came from .e.go

or an Etruscan version, and that Slovenian raca

was preserved from rako when its people became Slavicized in the

post-Roman era and that perhaps there is a distant connection with drake.)